15.2 Activities in Late Adulthood

Many elders complain that they do not have enough time each day to do all they want to do. This might come as a surprise to younger adults, who see few grey hairs at sports events, political rallies, job sites, or midnight concerts. In fact, most college and university students consider the elderly to be relatively passive and inactive, with plenty of time on their hands (Wurtele, 2009). Wrong.

540

Paid Work

Developmentalists are aware of the significant physical and psychological impacts that employment has on individuals and their families (Moen & Spencer, 2006). Work provides social support and status, boosting self-

Of course, many elders work because they need the money, increasingly so as pensions and investments shrink or disappear in the economic recession. This shrinkage is global. For example, riots and strikes in France, aimed at stopping the government from changing the age at which French citizens are granted government pensions, were unsuccessful. The age had been 60; as of 2011, it is 62. French workers must stay on the job longer now.

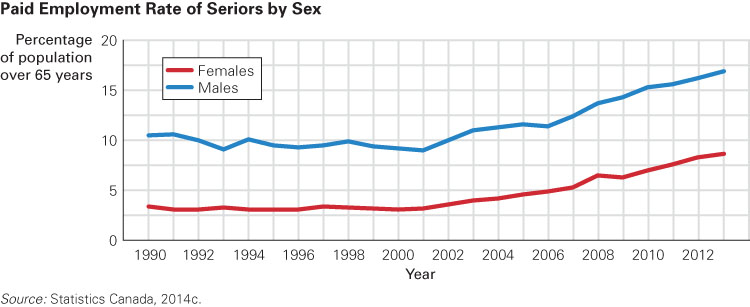

Participation in the labour force after age 60 is higher among non-

RetirementAre all older adults healthier and happier when they are employed? Not necessarily, although some people thought so, warning about “the presumed traumatic aspects of retirement” (Tornstam, 2005). In 2011, the Canadian Parliament passed the Keeping Canada’s Economy and Jobs Growing Act and amended the Canadian Human Rights Act to prohibit mandatory retirement. Now those Canadian workers older than 65 who wish to continue working may do so. If they are terminated, they must receive severance pay regardless of their age and pension eligibility (Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, 2012).

Canadian workers approach retirement in a number of ways. Some retire as soon as they can, while others keep working as long as they are able. Some choose a third path and ease their way into retirement by working part time for several years. One recent government survey found that those seniors who fully retired from work reported worse general health, with more chronic health issues and less physical activity, than seniors who continued to work either full or part time (Park, 2011).

541

BOOMER JERRITT/ALL CANADA PHOTOS

It is important to remember, however, that poor health may have influenced people’s decision to retire in the first place. For example, about 25 percent of full retirees stated that their health was the primary reason for retiring. About 40 percent of those who chose to keep working did so for financial reasons. More than one-

There is no doubt that employment and retirement can both cause distress. Planning and income are often inadequate; married couples may disagree as to who should retire, when retirement should begin, and how their lives should be restructured (Moen et al., 2005). Many retirees live longer than they expected, not having anticipated inflation, lost pensions, and increased health costs. After retirees’ initial activities—

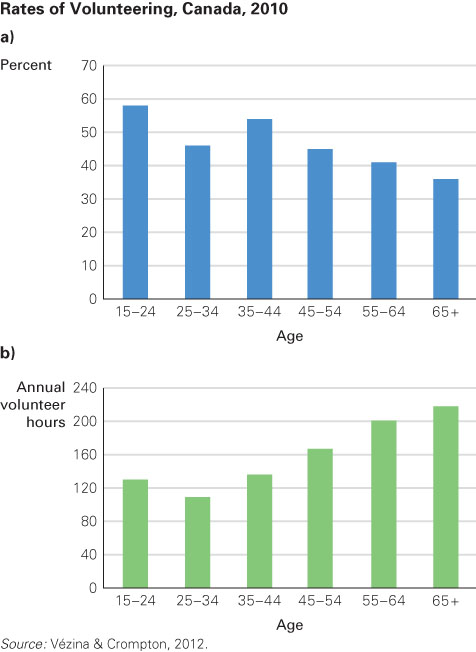

Volunteer WorkVolunteering offers some of the benefits of paid employment (generativity, social connections, less depression) and, consequently, is related to well-

Even though Canadian seniors are less likely to volunteer than the younger cohort aged 15 to 24 (36 percent versus 58 percent), those seniors who do volunteer average far more hours annually (218 hours versus 130, respectively) (see Figure 15.7). As self theory would predict, volunteer work attracts older people who always were strongly committed to their community and had more social contacts (Pilkington et al., 2012). Those who volunteer earlier in adulthood are more likely to continue volunteering in old age, becoming “mentors, guides, and repositories of experience” for younger people (Settersten, 2002). Because of their age and experience, senior volunteers tend to be “top volunteers,” defined as the top 25 percent of volunteers who put in 171 hours or more a year; in 2007, they accounted for 78 percent of total volunteering hours in Canada (Hall et al., 2009).

542

Seniors tend to focus their volunteer efforts in particular areas. In 2007, they logged more volunteering hours than any other age group working with religious organizations, hospitals, and social services organizations. In a government survey, they mentioned many reasons for volunteering their time, but the most common was that they believed it made a significant contribution to their community. They also reported that volunteering motivated them to build their social networks, that their friends volunteered, and that they wanted to meet people. Many also wished to continue using the skills and experience that they had spent years acquiring at work and at home (National Seniors Council, 2010).

Culture or national policy affects volunteering: Nordic elders (in Sweden and Norway) volunteer more often than Mediterranean ones (in Italy and Greece), differences that persist when illness is taken into account (Erlinghagen & Hank, 2006). The microsystem also has an effect. Being married to a volunteer makes it more likely that a person will volunteer also.

In light of the benefits, why are more elders not volunteering? Four possible explanations:

- Social culture. Ageism may discourage meaningful volunteering. Many volunteer opportunities are geared toward the young, who are attracted to intense, short-

term experiences. A week of building a house during reading week or two years of teaching in a developing nation are not designed for older volunteers (Morrow- Howell & Freedman, 2006– 2007). - Organizations. Institutions lack recruitment, training, and implementation strategies for attracting older volunteers. For instance, they may have systemic language and culture barriers that prevent people from volunteering; they may not be located in barrier-

free buildings; there may be a lack of access to public transportation for those older adults who no longer drive; or the organizations may not allow the flexible schedule that older adults require in order to accommodate travel, health concerns, medical appointments, and so on (Cook & Speevak Sladowski, 2013). - The elderly themselves. Older people may find it difficult to identify volunteer opportunities that suit their skills and circumstances. They may be reluctant to ask for accommodations to address their changing abilities. If they are not comfortable with technology, they may be intimidated by technology that they would use to carry out their volunteer work (Cook & Speevak Sladowski, 2012).

- The science. The problem may lie not with the people but with the definitions used in the research that tracks volunteerism. Surveys of volunteer work ignore daily caregiving and informal helping. Activities such as babysitting grandchildren, caring for an ill relative, and shopping for an infirm neighbour are not counted. If they were, the rates of volunteering among elders would be shown to be much higher.

543

Home Sweet Home

One of the favourite activities of many retirees is caring for their homes. Typically, both men and women do more housework and meal preparation (eating less fast food and more fresh ingredients) after retirement (Luengo-

Gardening is popular: Tending flowers, herbs, and vegetables is particularly beneficial during late adulthood because it is a productive activity that not only involves exercise but often promotes social interaction (Schupp & Sharp, 2012). Even the oldest-

In keeping up with household tasks and maintaining their property, many older people demonstrate that they prefer to age in place, rather than moving to another residence. That is the preference of most baby boomers as well: 83 percent of those aged 55 to 64 prefer to stay in their own homes when they retire (Koppen, 2009). If they must move, most older adults want to remain in their familiar neighbourhood, perhaps in a smaller apartment with an elevator, but not in a different city or province/territory. In fact, they are wise: Elders fare best when they are surrounded by friends and acquaintances, people who are difficult to replace. Gerontologists recognize that disrupting or altering social connections may be detrimental, particularly for women and those who are the frailest (Berkman et al., 2011).

In a 2011 review, Herbert Northcott and Courtney Petruik from the University of Alberta examined the geographic mobility of elderly Canadians. They found that most Canadian seniors do age in place, choosing not to move for long periods of time in their older years. Statistics indicate that in 2006, more than 70 percent of the older population had not moved in the last five years. Of the small percentage of Canadian seniors who did move, many moved locally, to neighbouring cities, towns, or villages (Northcott & Petruik, 2011).

Many seniors own their homes outright, having paid off their mortgages. For them, home ownership is a powerful motivator to stay in place. At least one Canadian researcher has found that older adults are generally not motivated to use their house for equity, either for moving to another place or for general spending (Ostrovsky, 2004). This finding agrees with research on elders in the United States and Europe. Seniors who do move may move for other reasons, such as poor health.

With the aging population increasing, houses are being built or remodelled to suit people with obvious visual, hearing, or motor difficulties as well as those for whom age has made it more difficult to reach high shelves, climb steep stairs, or respond to the doorbell. Universal design, which is the design of physical space and common tools (from computer screens to screwdrivers) so that people of all ages and all levels of ability can use them, is an emerging field.

Sometimes a neighbourhood or an apartment complex becomes a naturally occurring retirement community (NORC), a neighbourhood where people who moved in as young adults never move out. Many elderly people in NORCs are content to live alone. They stay on after their children have moved away or their partners have died, in part because they know the community and have friends there (C. C. Cook et al., 2007).

To age in place successfully, elderly people need many community services (K. Black, 2008). Aging in place does not mean seniors need to be left alone; it means that care should come to them (Golant, 2008).

544

Religious Involvement

ESPECIALLY FOR Religious Leaders Why might the elderly have strong faith but poor attendance at places of worship?

There are many possible answers, including the specifics of getting to places of worship (transportation, stairs), physical comfort in places of worship (acoustics, temperature), and content (unfamiliar hymns and language).

Older adults attend fewer religious services than do the middle-

In his later years, Maslow reassessed his final level, self-

Religious practices of all kinds are linked with physical and emotional health (Idler, 2006). Social scientists have found several reasons for this: (1) religious prohibitions encourage health (e.g., less drug use); (2) beliefs give meaning to life and death, thus reducing stress; and (3) joining a faith community increases social relationships (Atchley, 2009). In fact, a nearby house of worship, where not only their volunteer efforts but also their mere presence is valued, is one reason why elders prefer to age in place.

One Canadian study followed more than 12 000 people over the course of 14 years to track the connection between spirituality—

Religious identity and religious institutions are especially important for older members of minority groups, many of whom feel a stronger commitment to their religious heritage than to their national or cultural background. For example, elderly Ethiopians, Iraqis, and Turks tend to focus on their Muslim, or Christian, or Jewish faith rather than on their nationality (Gelfand, 2003). For all elderly people, no matter what their particular faith or ethnicity, psychological health depends on feeling that they are part of traditions that were handed down by their ancestors and will be carried on by their descendants.

Political Activism

In some respects, elderly people are not politically active. Few older people turn out for massive rallies, sign petitions, search for information on a political issue, or boycott or choose a product for ethical reasons (Turcotte & Schellenberg, 2006), and only about 8.6 percent of Canadians aged 55 and older reported being involved in political parties and campaigns. However, the performance rate for younger adults in this regard is even worse. Only 5.1 percent of people aged 25 to 54 were involved with a political party or group (Statistics Canada, 2011d).

By other measures, however, elder adults are more politically active than people of any other age. In Canada’s 2008 general election, only 58.8 percent of registered voters cast a vote. But according to that year’s General Social Survey, 89.4 percent of respondents aged 55 and older reported that they had voted in the election, compared with 75.8 percent of respondents aged 25 to 54, and 55.9 percent of those aged 18 to 24 (Statistics Canada, 2011d).

545

The elderly are also more likely than younger adults to keep up with the news. In 2003, 89 percent of seniors reported that they followed news and current affairs daily, compared to 68 percent for those between 25 and 54 years of age. This was true regardless of seniors’ education levels (Turcotte & Schellenberg, 2006).

CARP (formerly the Canadian Association of Retired Persons) is a national, nonpartisan, non-

KEY Points

- The elderly remain active in many ways, sometimes staying in the labour force when it is not financially necessary.

- Volunteering is an example of an activity that benefits individual health as well as the community.

- Retirement sometimes improves health and leads to more active involvement with home, neighbourhood, and religion.

- Compared with young adults, the elderly are more likely to be informed about current events and to vote.