15.3 Friends and Relatives

Humans are social animals, dependent on one another for survival and drawn to one another for joy. This is as true in late life as in infancy and at every stage in between. Remember from Chapter 13 that every person travels the life course in the company of other people, who make up the social convoy (Antonucci et al., 2007). Given that, it is not surprising that friends are particularly important in old age. Bonds formed over a lifetime allow people to share triumphs and tragedies with others who understand past victories and defeats. Siblings, old friends, and spouses are ideal convoy members.

Long-Term Partnerships

SEAN SPRAGUE/THE IMAGE WORKS

Spouses buffer each other against the problems of old age, thus extending life. This was one conclusion from a meta-

Elderly divorced people are lower in health and happiness than are those who are still married, although some argue that income and personality are the reasons, not marital status (Manzoli et al., 2007). Obviously, not every marriage is good for every older person: About one in every six long-

546

Nonetheless, happiness typically increases with the length as well as the quality of an intimate relationship—

In general, older couples have learned how to disagree. They consider their conflicts to be discussions, not fights. That is not unusual. In one U.S. study of long-

Outsiders might judge many long-

Given the importance of relationship building over the life span, it is not surprising that elders who are disabled (e.g., have difficulty walking, bathing, and performing other activities of daily life) are less depressed and anxious if they are in a close marital relationship (Mancini & Bonanno, 2006). A couple can achieve selective optimization with compensation: The one who is bedbound but cognitively alert can keep track of what the one who is mobile but experiences confusion is supposed to do, for instance.

Besides caregiving, sexual intimacy is another major aspect of long-

547

For most older couples, sexual interaction remains important (Johnson, 2007). This is true whether a couple is married or not married; a couple may cohabit, or, as discussed in Chapter 13, they may live apart together (LAT). Many elders—

Relationships with Younger Generations

In past centuries, many adults died before their grandchildren were born. By contrast, some families currently span five generations, consisting of elders and their children, grandchildren, great-

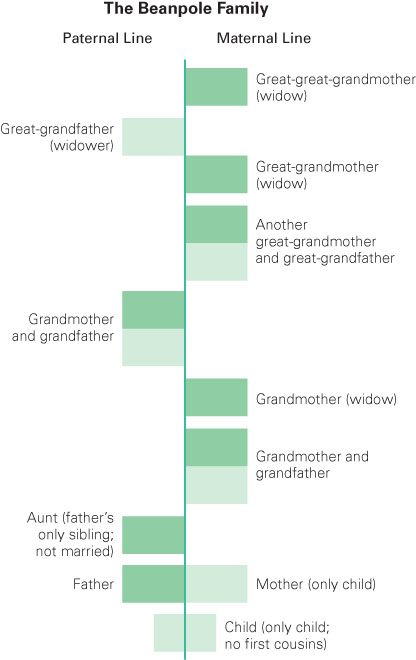

Since the average couple now has fewer children, the beanpole family, representing multiple generations but with only a few members in each, is becoming more common (see Figure 15.8) (Murphy, 2011). Some members of the youngest generation have no cousins, brothers, or sisters but a dozen elderly relatives. Intergenerational relationships are becoming more important as many grandparents have only one or two grandchildren.

Although elderly people’s relationships with members of younger generations are usually positive, they can also include tension and conflict. In some families, intergenerational respect and harmony abound whereas in others, members of one generation never see members of another. Each culture and, indeed, each family, have patterns and expectations for how the younger and oldest generations interact (Herlofson & Hagestad, 2011). Some conflict is commonplace.

For the most part, however, family members tend to support one another. As you remember, familism prompts siblings, cousins, and even more distant relatives to care for one another as adulthood unfolds. One manifestation of familism is filial responsibility, the obligation of adult children to care for their aging parents. This does not always work out well for either generation, but filial responsibility is a value in every nation, stronger in some cultures than in others (Saraceno, 2010).

When parents need caregiving, adult children often sacrifice to provide it. More often, though, the older generation gives to their adult children. This can strain a long-

When my daughter divorced, they nearly lost the house to foreclosure, so I went on the loan and signed for them. But then again they nearly foreclosed, so my husband and I bought it.…So now I have to make the payment on my own house and most of the payment on my daughter’s house, and that is hard.…I am hoping to get that money back from our daughter, to quell my husband’s sense that the kids are all just taking and no one is giving back. He sometimes feels used and abused.

[quoted in Meyer, 2012]

Emotional support and help with managing life may be more crucial and complex than financial assistance, sometimes increasing when money is less needed (Herlofson & Hagestad, 2012). One complexity is that some elders resent exactly the same supportive behaviours that other elders expect from their children—

548

A longitudinal study of attitudes found no evidence that recent changes in family structure (including divorce) reduce the sense of filial responsibility (Gans & Silverstein, 2006). In fact, younger cohorts (born in the 1950s and 1960s) endorsed more responsibility toward older generations, notwithstanding the sacrifices involved, than did earlier cohorts (born in the 1930s and 1940s). Likewise, almost all elders believe the older generation should help the younger ones, although specifics vary by culture (Herlofson & Hagestad, 2012).

In Canada and many other countries, every generation values independence. That is why, after midlife and especially after the death of their own parents, members of the older generation are less likely to say that children should provide substantial care for their parents and are more likely to strive to be helpful to their children. The authors of the longitudinal study just mentioned conclude that, as adults become more likely to receive than to give intergenerational care, “reappraisals are likely the result of altruism (growing relevance as a potential receiver) or role loss (growing irrelevance as a provider)” (Gans & Silverstein, 2006). Adults of all ages like to be needed, not needy.

This may be less true in Asian cultures. Often the first-

Tensions Between Older and Younger AdultsA good relationship with successful grown children enhances a parent’s well-

It is a mistake to think of the strength of the relationship as merely the middle generation paying back the older one for past sacrifices when they were children or young adults. Instead, family norms—

- Assistance arises both from need and from the ability to provide.

- Frequency of contact is related to geographical proximity, not affection.

- Love is influenced by the interaction remembered from childhood.

- Sons feel stronger obligation; daughters feel stronger affection.

Members of each generation tend to overestimate how much they contribute to the other (Lin, 2008b; Mandemakers & Dykstra, 2008). As already noted, contrary to popular perceptions, financial assistance and emotional support flow more often from the older generation down instead of from the younger generation up, although much depends on who needs what (Silverstein, 2006). Only when elders become frail (discussed later) are they more likely to receive family assistance than to give it.

GrandchildrenMost (80 percent of women and 74 percent of men) Canadians older than 65 are grandparents; over the next decade or so, a significant number of baby boomers will become grandparents, too. Some have coined a new term to describe this next stage of life for those born between 1946 and 1964: They will be known as “grandboomers” (“Grandparenting,” 2005). Personality, background, and past family interactions all influence the nature of the grandparent–

549

As with parents and children, the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren depends partly on the age of the grandchildren. One of my college students realized this when she wrote:

Brian and Brianna are twins and are turning 13 years old this coming June. Over the spring break my family celebrated my grandmother’s 80th birthday and I overheard the twins talking about how important it was for them to still have grandma around because she was the only one who would give them money if they really wanted something their mom wasn’t able to give them.…I lashed out…how lucky we were to have her around and that they were two selfish little brats. She’s the rock of the family and “the bank” is the least important of her attributes. …

[Giovanna, 2010]

In developed nations, grandparents fill one of four roles:

- Remote grandparents (sometimes called distant grandparents) are emotionally distant from their grandchildren. They are esteemed elders who are honoured, respected, and obeyed, expecting to get help whenever they need it.

- Companionate grandparents (sometimes called “fun-

loving” grandparents) entertain and “spoil” their grandchildren—especially in ways, or for reasons, that the parents would not. - Involved grandparents are active in the day-

to- day lives of their grandchildren. They live near them and see them daily. - Surrogate parents raise their grandchildren, usually because the parents are unable or unwilling to do so.

Currently, in developed nations, most grandparents are companionate, partly because all three generations expect them to be beloved older companions rather than authority figures. Contemporary elders are usually proud of their grandchildren and care about their well-

ATLANTIDE PHOTOTRAVEL/CORBIS

550

Such generative distance is not possible for grandparents who become surrogates when the biological parents are incapable of parenting; what results is a family structure called skipped generation because the middle generation is absent. Social workers often seek grandparents for kinship foster care, which works for the children as well as or better than foster care by strangers, but may be difficult for the older generation for many reasons:

- Both old and young are sad about the missing middle generation.

- Difficult grandchildren (such as drug-

affected infants and rebellious school- age boys) are more likely to live with grandparents. - Surrogate grandparents tend to be the most vulnerable elders, almost always grandmothers not grandfathers, already affected by past poverty.

For all these reasons, in North America and Europe, grandparents who are totally responsible for their grandchildren experience more illness, depression, and marital problems than do other elders (Hank & Buber, 2009; S. J. Kelley & Whitley, 2003). Stresses of all kinds abound, including worries about the children under their care (Shakya et al., 2012).

As for children of skipped-

Before concluding that grandparents raising children without the parents is always problematic for all three generations, we need to consider the circumstances. For instance, in China, many rural grandparents become full-

The fact that grandparenting is not always wonderful should not obscure the more typical situation: Most grandparents enjoy their role, gain generativity from it, and are appreciated by younger family members (C. L. Kemp, 2005; Thiele & Whelan, 2008). In most conditions, grandparenting benefits all three generations. Some grandparents are rhapsodic and spiritual about the experience. One writes:

Not until my grandson was born did I realize that babies are actually miniature angels assigned to break through our knee-

[M. Golden, 2009]

On the other side of the equation, even young adult grandchildren who are international students living thousands of kilometres away from their grandparents often express warmth, respect, and affection for at least one of them (usually their maternal grandmother) (A. C. Taylor et al., 2005).

Friendship

Recent widowhood or divorce is almost always difficult, but elderly people who have spent a lifetime without a spouse or a partner usually have friendships, activities, and social connections that keep them busy and happy (DePaulo, 2006). A study of 85 single elders found that their level of well-

551

This does not mean that loners are happy, however. All the research finds that older adults need at least one close companion. For many (especially husbands), their intimate friend is also a spouse; for others, the friend is another relative; for still others, it is an unrelated member of their social convoy.

Older adults may not recognize the need for a confidant until a relationship is severed. For example, one man consulted a therapist because he was unexpectedly depressed after retiring. He quit work when he chose to do so, expecting to be happy. The therapist noted, “For over forty years, he had car-

There is a lesson here: Many people do not realize the importance of social relationships until those relationships end. Quality (not quantity) of friendship is crucial, especially among the oldest-

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Social Networking, for Good or III

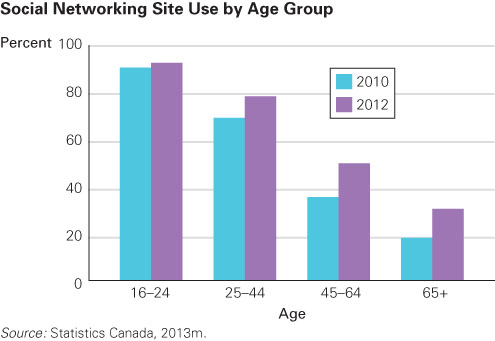

Older people text, tweet, post, and stream less than younger ones. Compared with emerging adults, older adults own fewer computers, are less connected to the Internet, and avoid social networking. One statistic makes the point: In Canada in 2012, 98.6 percent of all 16-

Older adults may not realize what they are missing: Seniors are significantly less likely than other age groups to realize that a lack of broadband access is a major disadvantage across a range of situations, such as making travel arrangements, researching investments, banking electronically, or accessing government services, with only one elder in nine considering lack of Internet connection “a major disadvantage” (A. Smith, 2010).

Age-

In fact from 2010 to 2012, the rates of social networking among those 65 and older increased by 60 percent, while rates for 16-

Richard Bosack joined Facebook on Thursday, after his buddy Ray Urbans recommended the ubiquitous social networking site a few days earlier. Bosack is 89. Urbans is 96.…The hottest growth segment in online social networking sites is guys like Richard and Ray and their lady friends. That’s right. Grampy and Grammy are down with “the Face.”

[Gregory, 2010]

552

From a developmental perspective, this may be good news. Elders who have strong social networks, close friends, and cognitively stimulating activities tend to live long and healthy lives. Involved, interacting elders are more cogent and happier than their relatively lonely and isolated peers. Internet use and social networking correlate with more frequent contact with friends, family, and community organizations (Hogeboom et al., 2010; Lewis & Ariyachandra, 2011).

Analysis of the characteristics of those who are not involved in social networking finds that old age itself is the characteristic they have most in common but that shyness and loneliness are also typical (Sheldon, 2012). Those who are networking are also less shy and less lonely—

Pause to appreciate the scope of the historical change in social networking. A few decades ago, social networks were maintained through direct contact. Neighbours were neighbourly, a word that means “friendly and helpful.” Everyone shopped, worshipped, studied, and played at the same places as everyone else, so they saw one another often. People always answered their phones and doorbells and complained if their friends did not “stay in touch,” which once meant literally touching, with a hug or a handshake. Today, most adults would be upset if a friend stopped by unannounced, although one study found that those over age 80 would not mind (Felmlee & Muraco, 2009).

Many elders today have dozens of face-

Then why is social networking a topic for “opposing perspectives” instead of celebration, with suggestions as to how to get more of the elderly online? Three reasons:

- Older adults’ first reaction to social media is negative. They worry especially about privacy.

- Social networking may increase prejudice.

- Virtual activism and involvement may decrease community activism.

First, privacy concerns. As you have read, many elders are fiercely independent, and they fear that social networking will make them vulnerable to strangers who want to sell them something, alter their habits, or change their lives (Sheldon, 2012). This concern is also expressed by people of all other ages; perhaps the elders, as a cohort, are more aware of the need for personal privacy than younger adults are.

Second, with wider access, people become more exclusive and selective about their contacts, lists, and news sources—

553

Third, although social networking increases the frequency of contact with friends, it may also decrease true intimacy and commitment. Writer Malcolm Gladwell (2010) explains:

The platforms of social media are built around weak ties… Facebook is a tool for effectively managing your acquaintances, for keeping up with the people you would not otherwise be able to stay in touch with.

[p. 42]

Weak ties, Gladwell contends, do not spur people to action; instead, they encourage comfort, lip service, and passivity—

Two eminent scholars, Thomas Sander and Robert Putnam (2010), fear that social networking will weaken social involvement. They hope that “technological innovators may yet master the elusive social alchemy that will enable online behavior to produce real and enduring civic effects” (p. 15), but they do not see it thus far. Furthermore, they note that posts on Twitter, or “tweets,” “convey people’s meal and sock choices, instant movie reactions, rush-

Two other social scientists conclude: “Changing social connectivity is, after all, neither a dystopian loss nor a utopian gain but an intricate, multifaceted, fundamental social transformation” (Wang & Wellman, 2010). Apparently all of us—

KEY Points

- Long-

term partnerships are beneficial, as research finds that married people tend to have longer, healthier, and happier lives than unmarried ones. - Adults who have never married tend to have strong social connections with friends, sometimes faring better than those who have been divorced or widowed.

- Children and grandchildren are important parts of the social network for many elders, who more often give care than receive it from the younger generations.

- Familism, not only in filial obligation but also in older parents caring for the younger generations, is apparent in every culture, expressed in divergent ways.