15.4 The Frail Elderly

Now that we have dispelled stereotypes by describing aging adults who are active and enjoy supportive friends and family, we can turn to the frail elderly—those who are infirm, very ill, seriously disabled, and/or cognitively impaired. They are not the majority, but they are also not rare: eventually about one-

554

Activities of Daily Life

The crucial indicator of frailty, according to insurance standards and medical professionals, is the inability to perform the tasks of self-

Equally important may be the instrumental activities of daily life (IADLs), which require intellectual competence and forethought. Indeed, problems with IADLs often precede problems with ADLs since planning and problem solving help frail elders maintain self-

| Domain | Exemplar Task |

|---|---|

| Managing medical care | Keeping current on check- |

| Assessing supplements as good, worthless, harmful | |

| Food preparation | Evaluating nutritional information on food labels Preparing and storing food to eliminate spoilage |

| Transportation | Comparing costs of car, taxi, bus, and train |

| Determining quick and safe walking routes | |

| Communication | Knowing when and whether to use landline, cell, texting, mail, email |

| Programming speed dial for friends, emergencies | |

| Maintaining household | Following instructions for operating an appliance |

| Keeping safety devices (fire extinguishers, CO2 alarms) active | |

| Managing one’s finances | Budgeting future expenses (housing, utilities, etc.) |

| Completing timely income tax returns |

Everywhere, the inability to perform IADLs makes people frail, even if they can perform all five ADLs. In 2003, the Canadian Community Health Survey reported that only 6 percent of senior men and 7 percent of senior women who were living in private households needed some level of assistance with their daily living (ADLs) (Gilmour & Park, 2006). As both a cause and a consequence, more of the elderly are living in the community rather than in assisted-

Whose Responsibility?There are marked cultural differences in care for the frail elderly, as already mentioned. As is true in many non-

Chinese courts have not hesitated to enforce the new law. For example, the People’s Court in Beitang district ordered a woman and her husband to visit the woman’s 77-

555

This new law has come into force as China faces the implications of a growing and significant older population; almost 14 percent of the country’s population is older than 60. At 194 million, China’s senior population is more than 5.5 times greater than Canada’s total population.

Demographics have changed in developed nations. Gerontologists note that one middle-

Preventing FrailtyGovernments, families, and aging individuals all have a role to play in preventing frailty. To take a simple example, leg muscles weaken in everyone in old age, but the individual, the social network, and the larger community all influence whether weakened leg muscles lead to frailty. Fear of falling might make a person walk rarely, preferring to stay in bed. Other people might encourage frailty: Perhaps an overly solicitous caregiver brings meals and an adult child buys a large-

To prevent frailty, the person could exercise daily, first in bed, then lying on the floor, then with machines to increase strength and daily excursions. Family members, friends, and volunteers could walk with that leg-

Consider another example, this one not theoretical:

A 70-

… He had a lapse of more than five years without proper control of his medical problems [hypertension and diabetes] because of difficulty gaining access to medical care…

Based on the medical history, a cognitive exam…and a magnetic resonance imaging of the brain…the diagnosis of moderate Alzheimer’s disease was made. Treatment with ChEI [cholinesterase inhibitors] was started… His family noted that his apathy improved and that he was feeling more connected with the environment.

[Grifith & Lopez, 2009]

556

In this example, you can see that both the community (those five years without treatment for hypertension and diabetes, both known to impair cognition) and the family (making excuses, protecting him) contributed to his reaching a stage of neuro-

The man himself was not blameless. If he had recognized his condition, he would have realized that travelling to Colombia was the worst thing he could do: Disorientation of place is an early symptom of neurocognitive disorder, and changing one’s physical (or geographic) location can make the problem worse. With many neurocognitive disorders, which cause severe IADL disability, as well as with all other kinds of physical and mental impairment, delay, moderation, and sometimes prevention are possible.

Caring for the Frail Elderly

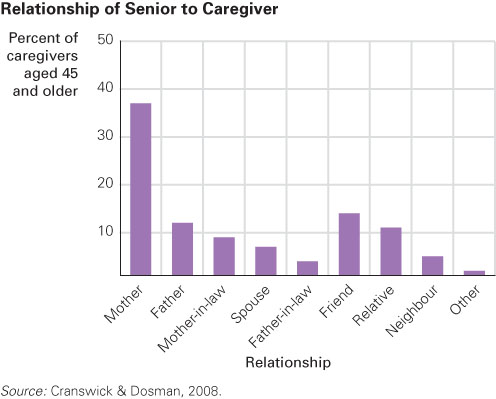

The caregiver of a married frail elderly person is usually the spouse, who is also elderly (Pinquart & Sörensen, 2011). If an impaired person has no partner, usually siblings or adult daughters become caregivers. Less often, sons and daughters-

Using a representative sample of 300 Quebec elders living at home, Réjean Hébert and colleagues at the University of Sherbrooke found that 70 to 80 percent of care for home-

Sometimes—

JEN WEN CHUN

Remember diversity, however, especially in attitudes, beliefs, and cultural practices. In northern European nations, most elder care is provided through a social safety net of senior daycare centres, senior homes, and skilled nurses. In some cultures, an older person who is dying is taken to a hospital; in other cultures, such intervention is seen as interference with the natural order. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, traditionally in Asian nations, a son’s wife provides elder care. In a 1990s study in South Korea, for instance, 80 percent of those with neurocognitive disorder were cared for by daughters-

557

Even with professional help, family caregivers experience substantial stress, although according to a longitudinal study, the stress is less when they receive practical help as well as emotional encouragement from other family members, even as the frail person’s needs increase (Roth et al., 2005). Conversely, without help, family caregivers experience less health and more depression. The stress is manifest in various illnesses, in part because the immune system weakens. This is particularly true when caregivers themselves are old (Lovell & Wetherell, 2011). After listing the problems and frustrations of caring for someone who is mentally incapacitated but physically strong, the authors of one overview note:

The effects of these stresses on family caregivers can be catastrophic… They may include increased levels of depression and anxiety as well as higher use of psychotropic medicine such as tranquilizers, poorer self-

[Gitlin et al, 2 003]

Even in ideal circumstances with cultural and community support, family caregiving can result in problems. For instance, if one adult child is the primary caregiver, other siblings may feel relief, and if the caregiver requests their help, they may resent being told what to do. On the other hand, if the parent develops a closer relationship with the primary caregiver, the other siblings may experience jealousy. In addition, care receivers and caregivers may disagree about schedules, menus, doctor visits, and so on. Resentments on both sides can disrupt mutual affection and appreciation.

In every culture, emotional and physical needs, as well as expectations, vary because of past experiences and current personalities. Some older people would rather accept help from a paid stranger than from a son or a daughter; others insist on the opposite. Some families admire caregivers and help them often; others isolate and resent them. A tradition of caregiving may explain why at least one study found that caregiving African-

Developmentalists are trained to see “change over time,” as Chapter 1 explains. From a life-

ESPECIALLY FOR Those Uncertain About Future Careers Would working in a nursing home be a good career for you?

It may be a good career choice. The demand for good workers will increase as the population ages, and the working conditions will improve. An important problem is that the quality of nursing homes varies, so you need to make sure you work in one whose policies incorporate the view that the elderly can be quite capable, social, and independent.

Developmentalists, concerned about the well-

558

Elder AbuseWhen caregiving results in resentment and social isolation, the risk of depression, poor health, and abuse (of either the frail person or the caregiver) escalates (Smith et al., 2011). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines elder abuse as: “A single, or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust that causes harm or distress to an older person” (WHO, 2002). Abuse is likely if the caregiver suffers from emotional problems or substance abuse, if the care receiver is frail and demanding, and if care location is an isolated place where visitors are few and far between.

Elder abuse can take several forms. Caregivers may resort to overmedication, locked bedroom doors, and physical restraints to cope with difficult patients. The next step may be improper feeding or rough treatment. In other cases, abuse may be financial more than physical—

Typically, abuse begins gradually and can continue for years without anyone realizing it. Abuse is generally not the result of one factor but of a combination of factors that can be heightened and complicated by various life events. Employment and Social Development Canada (2013) has noted some risk factors:

- a change in lifestyle (like retirement)

- employment or financial difficulties

- disputes over property/money

- physical illness

- mental/psychiatric illness

- addictions

- lack of adequate supports

- isolation

- changing relationships with family and/or friends

- declining independence.

Extensive public and personal safety nets for the frail elderly are needed. Most social workers and medical professionals are alert to the possibility of elder abuse and are suspicious if an elder is unexpectedly quiet, losing weight, or injured. However, when elder abuse is financial, bankers, lawyers, and investment advisors may not be able to recognize it nor are they obligated to respond (S. L. Jackson & Hafemeister, 2011).

A major problem is awareness: Professionals and relatives alike hesitate to criticize a family caregiver who is spending the pension cheque, disrespecting the elder, or simply not responding as quickly and carefully as the elder wishes. At what point does this become abuse? This is an issue for all cultures, incomes, and families.

Sometimes the caregiver becomes the victim, cursed at or even attacked by the confused elderly person. As with other forms of abuse, the dependency of the victim makes prosecution difficult (Mellor & Brownell, 2006).

Researchers find that about 5 percent of elders say they are abused and that up to 25 percent of all elders are vulnerable but do not report abuse (Cooper et al., 2008). Elders who are mistreated by family members are often ashamed to admit it, so the actual rate of abuse is probably close to 25 percent. Accurate incidence data are complicated by lack of consensus regarding standards of care: Some elders feel abused, but caregivers disagree. It is known that elders who are mistreated are more likely to be depressed and ill, but neither of these conditions proves abuse (Dong et al., 2011).

559

Long-

I would rather die than have to exist in such a place where residents are neglected, ignored, patronized, infantilized, demeaned; where the environment is chaotic, noisy, cold, clinical, even psychotic.

[quoted in W.H. Thomas, 2007]

Among the signs of a humane setting are provisions for independence; individual choice—

The training and the workload of the staff, especially of the aides who provide the most frequent and most personal care, are crucial: Such simple tasks as helping a frail person out of bed can be done clumsily, painfully, or skillfully. The difference depends on proficiency, experience, and patience—

Quality care is much more labour-

In North America and particularly in western Europe, good private nursing-

Although 90 percent of elders are independent and community dwelling at any given moment, half of them will need nursing-

560

Alternative CareMost elder-

An assisted-

Assisted-

Another form of alternative care is sometimes called village care. Although not really a village, it is so named because of the African proverb “It takes a whole village to raise a child.” The idea is that if elderly people who live near one another all pool their resources, they can stay in their homes but also have special assistance when they need it. Such communities require that the elderly contribute financially and that they be relatively competent, so village care is not suited for everyone. However, for some it is ideal (Scharlach et al., 2012).

Overall, as with many other aspects of aging, the emphasis in living arrangements is on selective optimization with compensation. Elders need to live in settings that allow them to be at their best, safe and respected, in control of as much of their own lives as possible. Depending not only on the specifics of ADLs and IADLs, but also on the personality of the elder and the depth of the social network, many housing solutions are possible. One expert explains: “There is no one-

VALDRIN XHEMAJ/EPA/NEWSCOM

We close with an example of family care and nursing-

561

Fortunately, this nursing home encouraged independence and did not assume that decline is always a sign of “final failing.” The doctors there discovered that the woman’s heart pacemaker was not working properly. Rob tells what happened next:

We were very concerned to have her undergo surgery at her age, but we finally agreed.…Soon she was back to being herself, a strong, spirited, energetic, independent woman. It was the pacemaker that was wearing out, not Great-

[quoted in L. P. Adler, 1995]

This story contains a lesson repeated throughout this book. When a toddler does not talk, or a preschooler grabs a toy, or a teenager gets drunk, or an emerging adult takes dangerous risks, or a newlywed contemplates divorce, or an older person seems to be failing, one might conclude that such problems are normal for that particular age. There is truth in that: Each of these is more common at those stages. But each of these behaviours should also alert caregivers to encourage talking, sharing, moderation, caution, or self-

KEY Points

- The frail elderly are unable to perform activities of daily life (ADLs) such as feeding, dressing, and bathing themselves.

- Instrumental activities of daily life (IADLs) require intellectual competence and may be more crucial for independent living than ADLs.

- Caregiving of the frail elderly can be depressing or satisfying, depending partly on support from professionals, family members, and the care receiver.

- Professional help, in assisted-

living facilities or nursing homes, can be beneficial or dehumanizing.