1.1 Understanding How and Why

The science of human development seeks to understand how and why people—

Developmentalists recognize that growth over the life span is multidirectional, multi-

Science is especially necessary when the topic is human development: Lives depend on the answers. People disagree vehemently about what pregnant women should eat, whether babies should be left to cry, when children should be punished, under which circumstances adults should marry, or divorce, or retire, or die. Opinions are subjective, arising from emotions and culture. Scientists seek to progress from opinion to truth, from subjective to objective, from wishes to evidence.

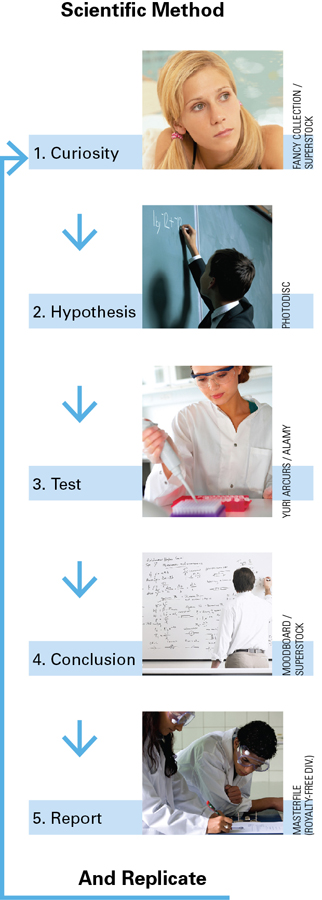

The Scientific Method

As you may realize, facts may be twisted, and applications sometimes spring from assumptions, not from data. To avoid unexamined opinions and to rein in personal biases, researchers follow five steps of the scientific method (see Figure 1.1):

- Begin with curiosity. On the basis of theory, prior research, or a personal observation, pose a question.

- Develop a hypothesis. Shape the question into a hypothesis, a specific prediction that can be tested.

- Test the hypothesis. Design and conduct research to gather empirical evidence (data).

5

- Draw conclusions. Use the evidence to support or refute the hypothesis.

- Report the results. Share the data, conclusions, and alternative explanations.

As you see, developmental scientists begin with curiosity and then seek the facts, drawing conclusions after careful research. Replication—repeating the procedures and methods of a study with different participants—

The implications of those conclusions spread beyond science, involving religion, politics, and ethics. One of the most famous scientists of all time said, “Science without religion is lame; religion without science is blind” (Einstein, 1954/1994). Some of the politics and ethics of scientific research are discussed at the end of this chapter. Every chapter of this book, and every “Opposing Perspectives” feature, describes the interaction of empirical data with moral values.

The Nature–Nurture Controversy

A good example of the need for science concerns a great puzzle of development, the nature–

The nature–

Developmentalists have learned that neither belief by itself is accurate. The question is “how much,” not “which,” because both genes and the environment affect every characteristic: Nature always affects nurture, and then nurture affects nature. Some scientists think that even “how much” is misleading, as it implies that nature and nurture each contribute a fixed amount when actually their dynamic interaction is crucial (Gottlieb, 2007; Meaney, 2010; Spencer et al., 2009). I fainted at Caleb’s birth because of the interaction of at least seven factors (low blood sugar, lack of sleep, physical exertion, gender, age, relief, joy), all influenced by both nature and nurture, all combining to land me on the floor.

6

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Sudden Infant Death*

Coverage of every topic in this book is based on research that follows the scientific method. Here we present one topic, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), to illustrate. Every year until the mid-

Then a scientist named Susan Beal studied every SIDS death in South Australia, seeking factors that might be causes. She learned that some circumstances did not matter (such as birth order) and others increased the risk (such as maternal smoking and lambskin blankets).

A breakthrough came when Beal noticed an ethnic variation: Australian babies of Chinese descent died far less often of SIDS than did Australian babies of European descent. Genetic? Most experts thought so. But Beal’s scientific observation led her to note that Chinese babies slept on their backs, contrary to the Australian (as well as European and North American) custom of stomach-

To test her hypothesis (step 3), Beal convinced a large group of non-

In Canada in 1993, the federal government and several public health organizations began recommending that parents place their babies on their backs to sleep. SIDS rates had been falling since the late 1980s, but after the government launched a formal “Back to Sleep” campaign in 1999, the rate of SIDS in Canada fell by 50 percent over the next five years. Researchers believe this significant reduction can be directly linked to the increase in the number of babies who were put to sleep on their backs, as well as to lower smoking rates among pregnant women.

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Back-

The swaddling blanket is not only folded under the baby but is also tied in place.

Stomach-

*Each chapter includes a feature entitled A View From Science that is intended to help readers to understand the scientific process as well as to learn details of a topic of interest. For both reasons, don’t skip over these features.

7

KEY points

- The study of development is a science that seeks to understand how and why each individual is affected by the changes over the life span.

- As a science, developmental research follows five main steps: question, hypothesis, empirical research, conclusions based on data, and publication.

- A sixth step, replication, confirms, refutes, or refines conclusions of a scientific study.

- Nature and nurture affect every human characteristic, in a dynamic interaction between genes and the environment.