1.3 Theories of Human Development

As you read earlier in this chapter, the scientific method begins with observations, questions, and theories (step 1). These lead to specific hypotheses that can be tested (step 2). A theory is a comprehensive and organized explanation of many phenomena; a hypothesis is more limited and may be proven false. Theories are generalities; hypotheses are specific. Data are collected through research (step 3), conclusions are drawn (step 4), and the results are reported (step 5) and replicated.

Although developmental scientists are intrigued by all their observations, theories are crucial to start the scientific process. Theories sharpen their perceptions and organize the thousands of behaviours they observe every day. Every developmental theory is a systematic statement of principles and generalizations, providing a framework for understanding how and why people change over the life span. We need theories to “help us describe and explain developmental changes by organizing and giving meaning to facts and by guiding future research” (P. H. Miller, 2011). Theories connect facts with patterns, weaving the details of life into a meaningful whole.

You will encounter dozens of theories throughout this text, each one useful in organizing data and developing hypotheses. Six major theories that apply to the entire life span are introduced here; more details about each of them appear later in this text.

Psychoanalytic Theory

Inner drives and motives are the foundation of psychoanalytic theory. These basic underlying forces are thought to influence every aspect of thinking and behaviour, from the smallest details of daily life to the crucial choices of a lifetime (Dijksterhuis & Nordgren, 2006). Psychoanalytic theory is often treated as a stage theory because it sees each child going through distinct and sequential levels or stages. Each stage in a child’s development builds upon the last and prepares for the next. For example, in developing math skills, children need to learn what numbers are before they can add. Once they can add, the next step is subtraction, then multiplication, and then division. Skipping or failing to master one stage will lead to problems in the next. Many psychoanalytic theorists believe that human development proceeds in just such a fashion, in clearly defined and complementary stages.

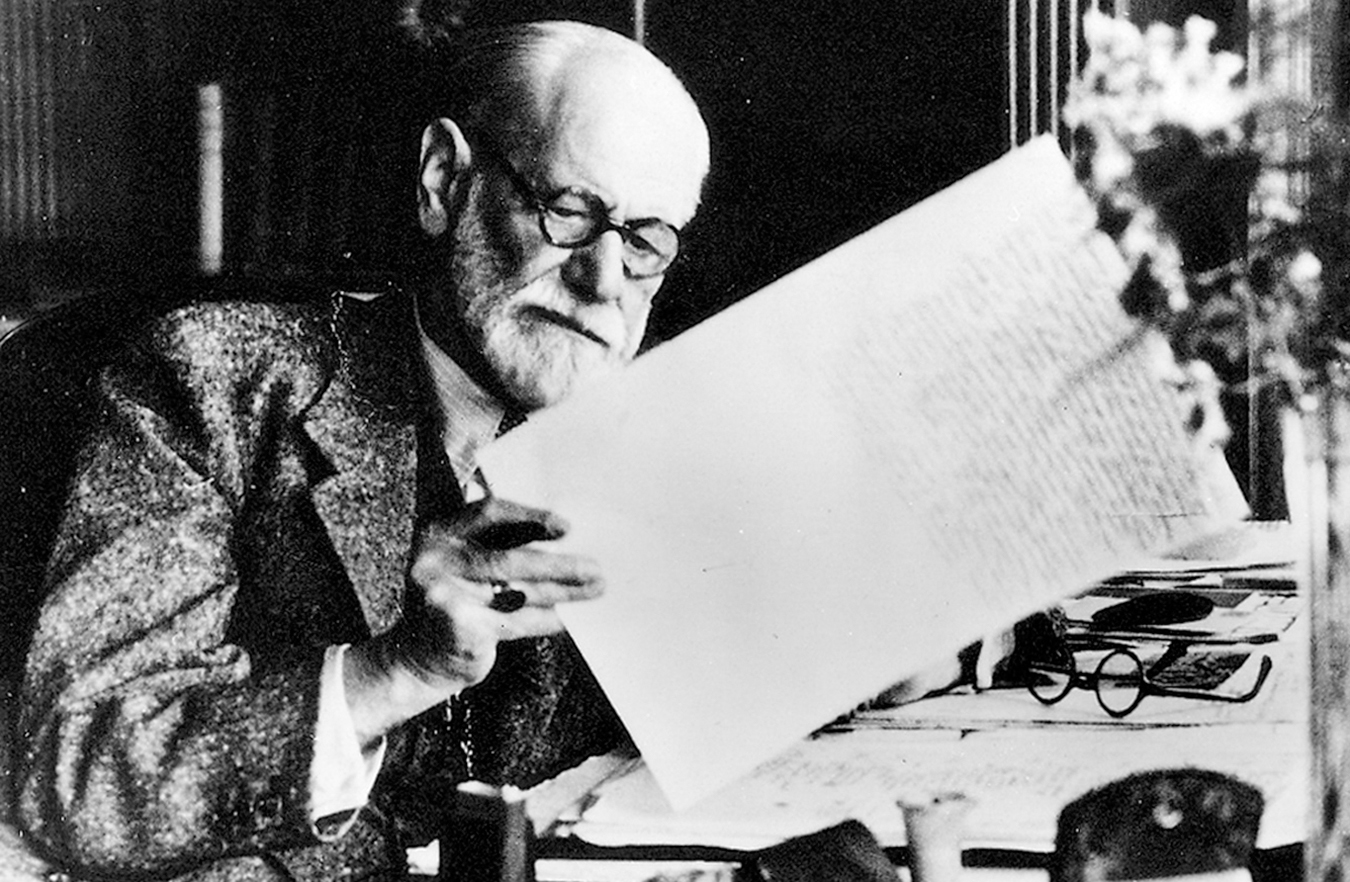

Freud’s StagesPsychoanalytic theory originated with Sigmund Freud (1856–

According to Freud, development in the first six years occurs in three stages, each characterized by sexual pleasure centred on a particular part of the body. Infants experience the oral stage, so named because the erotic body part is the mouth, followed by the anal stage in early childhood, with the focus on the anus. In the preschool years (the phallic stage), the penis becomes a source of pride and fear for boys and a reason for sadness and envy for girls.

In middle childhood comes latency, a quiet period that ends when one enters the genital stage at puberty. Freud was the most famous theorist who thought that development stopped after puberty and that the genital stage continued throughout adulthood (see TABLE 1.3).

| Approximate Age | Freud (Psychosexual) | Erikson (Psychosocial) |

|---|---|---|

| Birth to 1 year | Oral Stage | Trust vs. Mistrust |

| The lips, tongue, and gums are the focus of pleasurable sensations in the baby’s body, and sucking and feeding are the most stimulating activities. | Babies either trust that others will care for their basic needs, including nourishment, warmth, cleanliness, and physical contact, or develop mistrust about the care of others. | |

|

1- |

Anal Stage | Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt |

| The anus is the focus of pleasurable sensations in the baby’s body, and toilet training is the most important activity. | Children either become self- |

|

|

3- |

Phallic Stage | Initiative vs. Guilt |

| The phallus, or penis, is the most important body part, and pleasure is derived from genital stimulation. Boys are proud of their penises; girls wonder why they don’t have one. | Children either want to undertake many adult- |

|

|

6- |

Latency | Industry vs. Inferiority |

| Not really a stage, latency is an interlude during which sexual needs are quiet and children put psychic energy into conventional activities like schoolwork and sports. | Children busily learn to be competent and productive in mastering new skills or feel inferior, unable to do anything as well as they wish they could. | |

| Adolescence | Genital Stage | Identity vs. Role Confusion |

| The genitals are the focus of pleasurable sensations, and the young person seeks sexual stimulation and sexual satisfaction in heterosexual relationships. | Adolescents try to figure out “Who am I?” They establish sexual, political, and vocational identities or are confused about what roles to play. | |

| Adulthood | Freud believed that the genital stage lasts throughout adulthood. He also said that the goal of a healthy life is “to love and to work.” |

Intimacy vs. Isolation Young adults seek companionship and love or become isolated from others because they fear rejection and disappointment. |

| Generativity vs. Stagnation | ||

| Middle- |

||

| Integrity vs. Despair | ||

| Older adults try to make sense out of their lives, either seeing life as a meaningful whole or despairing at goals never reached. |

Freud maintained that at each stage, sensual satisfaction (from stimulation of the mouth, anus, or genitals) is linked to developmental needs, challenges, and conflicts. How people experience and resolve these conflicts—

25

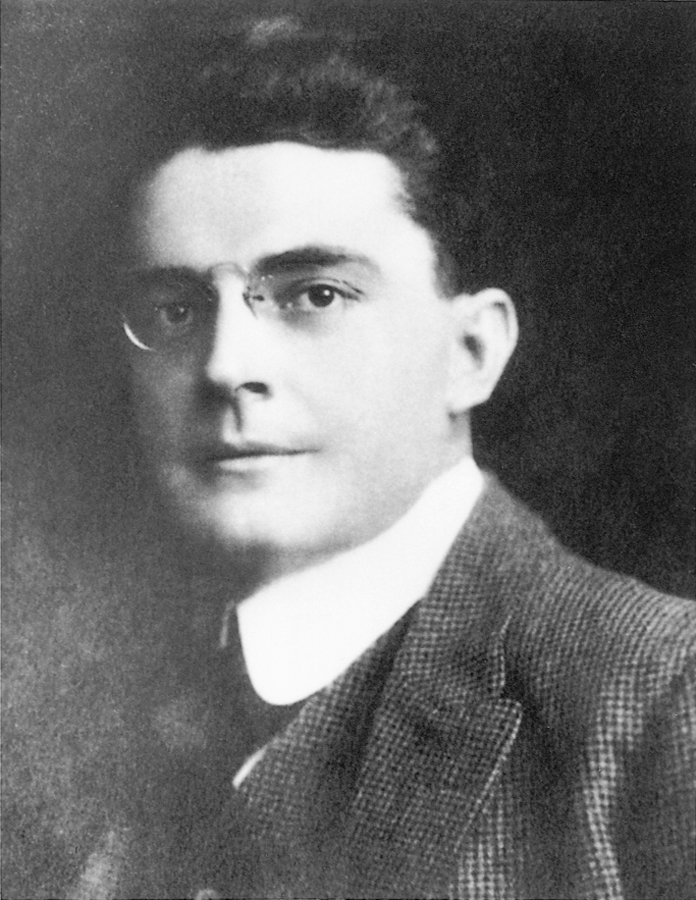

Erikson’s StagesMany of Freud’s followers became famous theorists themselves. The most notable in human development was Erik Erikson (1902–

26

Erikson named two polarities at each stage (which is why the word versus is used in each), but he recognized that many outcomes between these opposites are possible (Erikson, 1963). For most people, development at each stage leads to neither extreme. For instance, the generativity-

Like Freud, Erikson believed that adults’ problems echo their childhood conflicts. For example, an adult who cannot form a secure, close relationship with someone else (intimacy versus isolation) may not have resolved the crisis of infancy (trust versus mistrust). However, Erikson’s stages differ significantly from Freud’s in that, first, Erikson’s theory was a life-

Before psychoanalytic theory, most scientists ignored the first years of life. Both Freud and Erikson noted that psychological conflicts—

Learning Theory

From the beginning, psychoanalytic theory was criticized by scientists who said it was difficult to measure internal motives and drives, especially those stemming from the unconscious mind. Out of this criticism came learning theory, which focuses on overt behaviours that can be directly observed. Learning theory argues that behaviour is influenced by the social environment and by how people are rewarded or punished when they act in certain ways. Two important learning theories are behaviourism and social learning theory.

BehaviourismBehaviourism arose in direct opposition to the psychoanalytic emphasis on unconscious, hidden urges (differences are described in TABLE 1.4). Early in the twentieth century, John B. Watson (1878–

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-

[Watson, 1924/1998]

Many other psychologists, especially in the United States, agreed. They found that the unconscious motives and drives that Freud described were difficult (or impossible) to verify via the scientific method (Uttal, 2000). For instance, researchers found that, contrary to Freud’s view, parents’ approach to toilet training did not determine a child’s later personality. Thus, behavioural psychologists believed that what children learn, especially in regard to social behaviour, is acquired from their environment.

| Area of Disagreement | Psychoanalytic Theory | Behaviourism |

|---|---|---|

| The unconscious | Emphasizes unconscious wishes and urges, unknown to the person but powerful all the same | Holds that the unconscious not only is unknowable but also may be a destructive fiction that keeps people from changing |

| Observable behaviour | Holds that observable behaviour is a symptom, not the cause— |

Looks only at observable behaviour— |

| Importance of childhood | Stresses that early childhood, including infancy, is critical; even if a person does not remember what happened, the early legacy lingers throughout life | Holds that current conditioning is crucial; early habits and patterns can be unlearned, even reversed, if appropriate reinforcements and punishments are used |

| Scientific status | Holds that most aspects of human development are beyond the reach of scientific experiment; uses ancient myths, the words of disturbed adults, dreams, play, and poetry as raw material | Is proud to be a science, dependent on verifiable data and carefully controlled experiments; discards ideas that sound good but are not proven |

For every individual at every age, from newborn to centenarian, behaviourists have identified laws to describe how environmental responses shape what people do. All behaviour, from reading a book to robbing a bank, follows these laws. Every action is learned, step by step. As the saying goes, “monkey see, monkey do.”

27

ConditioningThe specific laws of learning apply to conditioning, the processes by which responses become linked to particular stimuli. There are two types of conditioning: classical and operant.

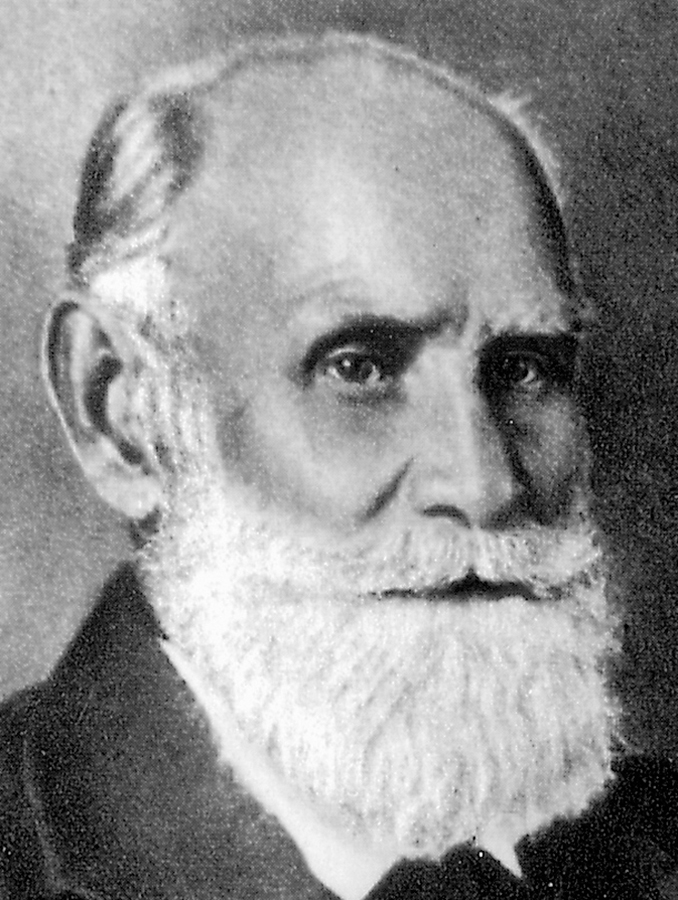

More than a century ago, Ivan Pavlov (1849–

Pavlov began by ringing a bell just before presenting food to the dogs. After a number of repetitions of the ringing-

The most influential North American behaviourist was B. F. Skinner (1904–

28

Any consequence that follows a behaviour and makes the person (or animal) likely to repeat that behaviour is called a positive reinforcement, not a reward. Once a behaviour has been conditioned, humans and other creatures will repeat it even if reinforcement occurs only occasionally. Similarly, an unpleasant response makes a creature less likely to repeat a certain action.

This insight has practical application. Early responses are crucial for development because children learn habits that endure. For example, when I was a child, my father would come home, announce his arrival, and hope to be greeted by his four children, to no avail. So at one point, he started yelling out, “Chocolate bars!” whenever he arrived home, and we all came running to pull the treats from his pockets. After a while, the chocolate bars stopped, but by then we had developed the habit of giving our father a warm welcome at the end of the day. In this way, my father reinforced family solidarity.

The science of human development has benefitted from behaviourism. The theory’s emphasis on the origins and consequences of observed behaviour led to the realization that many actions that seem to be genetic, or to result from deeply rooted emotional problems, are actually learned. And if something is learned, it can be unlearned. No longer are “the events of infancy and early childhood…the foundation for adult personality and psychopathology,” as psychoanalysts believed (Cairns & Cairns, 2006). People can change; plasticity continues throughout one’s life.

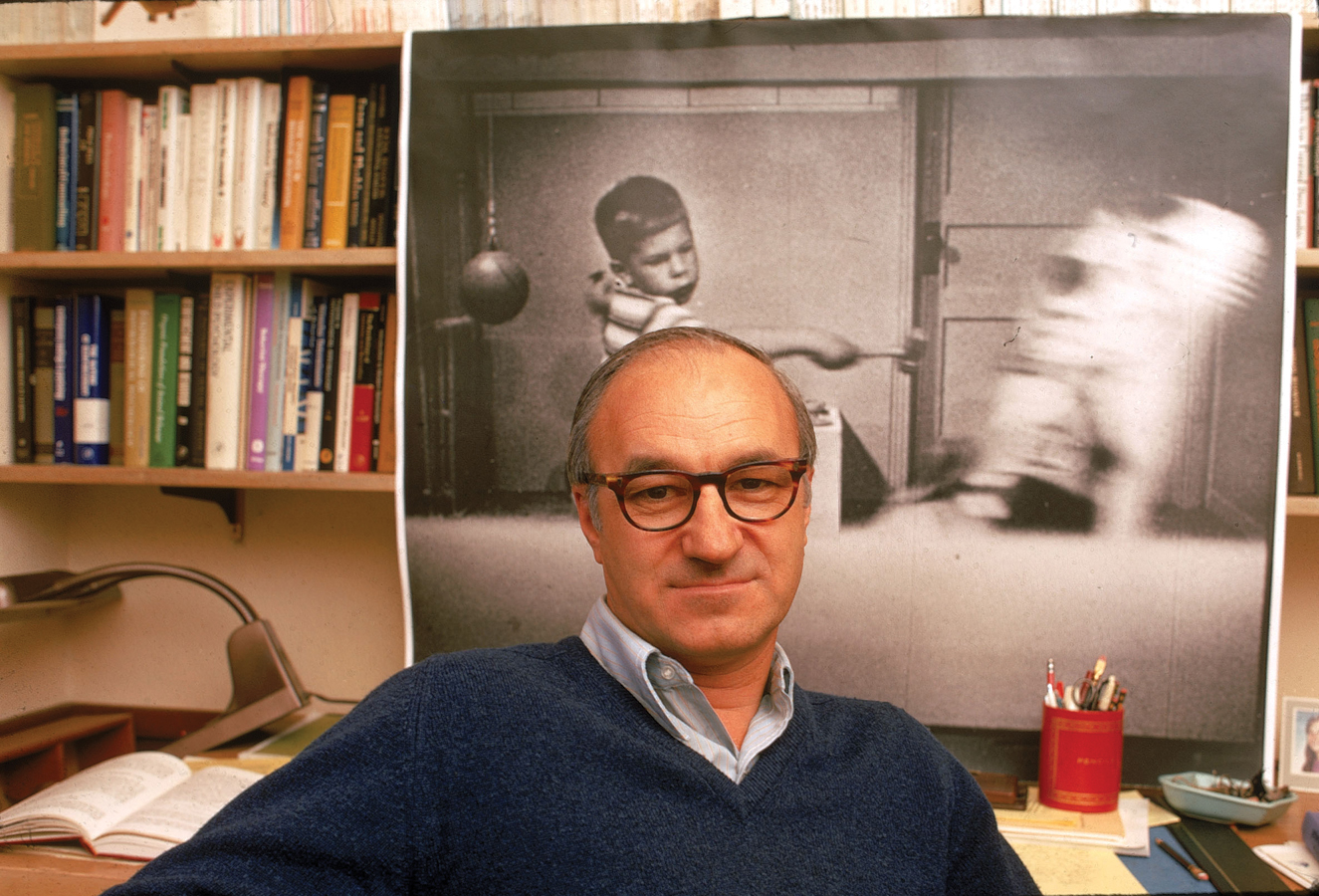

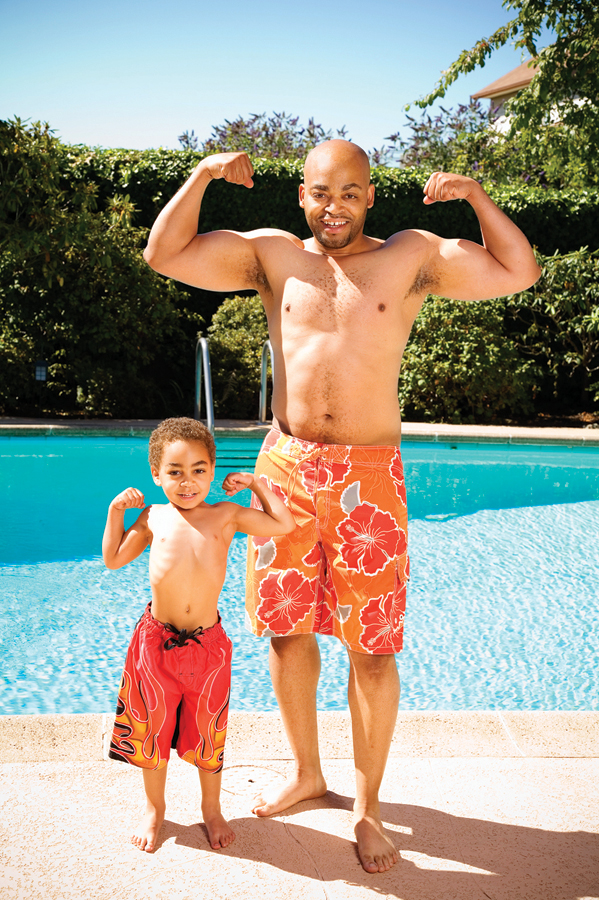

Social Learning TheoryA major extension of behaviourism is social learning theory, which was first described by Albert Bandura (b. 1925), who was born and raised in Alberta. He is currently a professor emeritus at Stanford University. Social learning theory notes that, because humans are social beings, they learn from observing others, even without personally receiving any reinforcement.

This form of learning theory is often called modelling because people learn by observing role models. For example, researchers have found that children who witness domestic violence are influenced by it. As the multicontextual approach would predict, what they learn varies. In a family in which the father often hits the mother, one son might identify with the abuser and another with the victim. Later in adulthood, because of their past social learning, one man might slap his wife and spank his children, while his brother might be fearful and apologetic at home. They learned opposite lessons. Differential sensitivity may also be evident: a third sibling may not be affected in adulthood by past memories of domestic violence.

29

Cognitive Theory

In a third type of theory, each person’s ideas and beliefs are of central importance. According to cognitive theory, thoughts and expectations profoundly affect actions. Cognitive theory has dominated psychology since about 1980 and has branched into many versions, each adding insights about human development. The word cognitive refers not just to thinking but also to attitudes, beliefs, and assumptions.

The most famous cognitive theorist was a Swiss scientist, Jean Piaget (1896–

From this work, Piaget developed the central theme of cognitive theory: How people think (not just what they know) changes with time and experience, and human thinking influences human actions. Piaget maintained that cognitive development occurs in four major age-

| Age Range | Name of Period | Characteristics of the Period | Major Gains During the Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth to 2 years | Sensorimotor | Infants use senses and motor abilities to understand the world. Learning is active; there is no conceptual or reflective thought. | Infants learn that an object still exists when it is out of sight (object permanence) and begin to think through mental actions. |

|

2– |

Preoperational | Children think magically and poetically, using language to understand the world. Thinking is egocentric, causing children to perceive the world from their own perspective. | The imagination flourishes, and language becomes a significant means of self- |

|

6– |

Concrete operational | Children understand and apply logical operations, or principles, to interpret experiences objectively and rationally. Their thinking is limited to what they can personally see, hear, touch, and experience. | By applying logical abilities, children learn to understand concepts of conservation, number, classification, and many other scientific ideas. |

| 12 years through adulthood | Formal operational | Adolescents and adults think about abstractions and hypothetical concepts and reason analytically, not just emotionally. They can be logical about things they have never experienced. | Ethics, politics, and social and moral issues become fascinating as adolescents and adults take a broader and more theoretical approach to experience. |

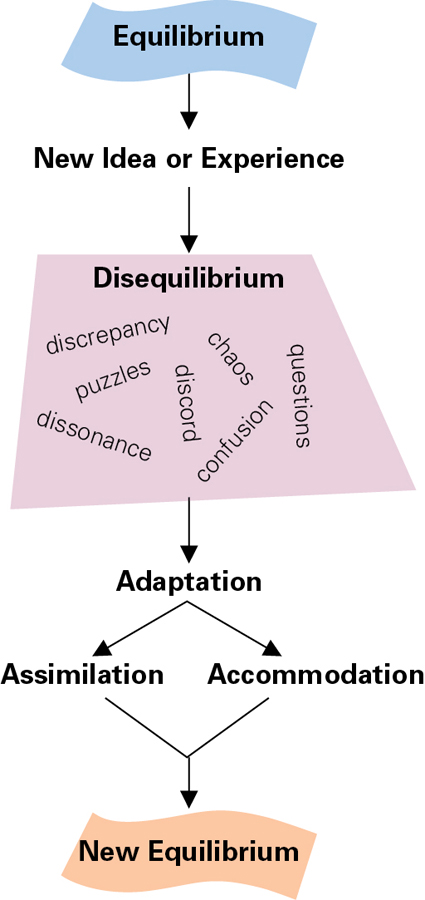

Intellectual advancement occurs throughout one’s life because humans seek cognitive equilibrium—that is, a state of mental balance. An easy way to achieve this balance is to interpret new experiences through the lens of pre-

Sometimes, however, a new experience is jarring and incomprehensible. The resulting experience is one of cognitive disequilibrium, an imbalance that initially creates confusion. As Figure 1.10 illustrates, disequilibrium leads to cognitive growth because it forces people to adapt their old concepts. Piaget describes two types of adaptation:

- Assimilation, in which new experiences are interpreted to fit into, or assimilate with, old ideas

- Accommodation, in which old ideas are restructured to include, or accommodate, new experiences.

30

Accommodation requires more mental energy than assimilation, but it is sometimes necessary because new ideas and experiences may not fit into existing cognitive structures. Accommodation produces significant intellectual growth. For example, think of cognitive structures as filing cabinets. A child has a family cat that is black and white. Learning that this animal is called a “cat,” the child creates a “cat folder.” When the child meets a brown cat, she has no trouble learning that in spite of its difference in colour, it is also a “cat” and can be filed away into the “cat folder.”This new information becomes assimilated (added) in the “cat folder.” Now, when the child meets a dog, she may at first think that it’s a cat, since it also has four legs and a long tail. However, her parents tell her that this new animal is actually a dog! She now needs to make a “dog folder” to accommodate this new information.

Another influential cognitive theory, called information processing, differs from Piaget’s theory. Information-

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Behind the posturing, what indicates that this boy models himself after his parent?

The swimsuit. Not only has the boy chosen a swimsuit that is the same style as his father’s, but he has chosen a swimsuit that is the same colour as his father’s.

Systems Theory

Many useful twenty-

Human development depends on systems. Consider examples from the three domains of development. Some systems are physiological, such as the immune system, which includes many kinds of immune cells. Some systems are cognitive, such as language, with sounds, words, and grammar all working together to produce communication. And some are social, such as the members of a family, workers in a factory, or citizens of a town. Minor dysfunctions can be overcome, but a major dysfunction can bring the whole system to a dead stop.

We have already considered one important systems theory earlier in this chapter, Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological-

Family Systems TheoryAs Bronfenbrenner focused on various microsystems to help explain development, family systems theory focuses on the family as a unit or functioning system with its own set of rules that keep it operating over time. Systems theory is useful in understanding the complex interactions among family members, including the way they make decisions, set and achieve certain goals, and create rules to regulate behaviours. Much of family systems theory developed from the work and writings of the renowned therapist Salvador Minuchin (b. 1921) in the 1970s.

31

PHOTOTODISK/PUNCHSTOCK

According to Minuchin (1974), it is impossible to understand how families operate without considering the concept of wholeness. Each family member makes up a part of the whole, and each member is connected with every other member. This interdependence of family members means that what affects one has an effect on every other member and on the family as a whole.

Think of a time in your own family history when something significant happened. Perhaps your grandfather died, your mother got a promotion that meant moving to another city, or your parents divorced. Whether for good or bad, the whole family has to react in such a situation, and every reaction results in some kind of change. Whenever this happens, the family system makes an effort to stabilize itself, to return to a state of balance or what theorists call homeostasis.

The way family members influence each other in a back-

Over time, patterns emerge in every family whereby behaviours become regulated, allowing each member to anticipate other members’ actions. Three factors are responsible for regulating behaviours: rules, roles, and communication styles.

Parents or guardians usually decide what the rules will be, providing a common understanding for acceptable and unacceptable behaviours. Rules can either be explicit, as when parents tell teens exactly what their curfew is, or implicit, as when it is simply understood that children will enhance their career prospects by going to university or college.

32

Each person assumes a specific role in the family (as mother, father, son, or daughter), and with a role comes a set of expected behaviours and responsibilities. For instance, a 15-

Communication styles are important in determining the quality of family relationships. There are three types of communication styles: verbal, nonverbal, and contextual. Verbal communications consist of the words spoken out loud among family members. These words are usually accompanied by some type of nonverbal communication such as bodily gestures and facial expressions. Both verbal and nonverbal communications are delivered within a specific context that usually enhances the message in some way. For example, when parents force a child to say “sorry,” this is a very different context from when a child spontaneously and willingly offers an apology (Beevar & Beevar, 1998).

As families develop their own unique sets of patterns, they also create certain boundaries that are useful in setting limits for acceptable behaviours. Boundaries can either strengthen or weaken the health of a family system. Families that are open systems have boundaries that are flexible, and they are willing to exchange information and interactions with other families and individual people. In contrast, closed systems set inflexible boundaries and are unwilling to accept outside information and interactions. For example, many families refuse to discuss mental health issues or to seek therapy for a family member until the illness has escalated to a dangerous level.

Humanism

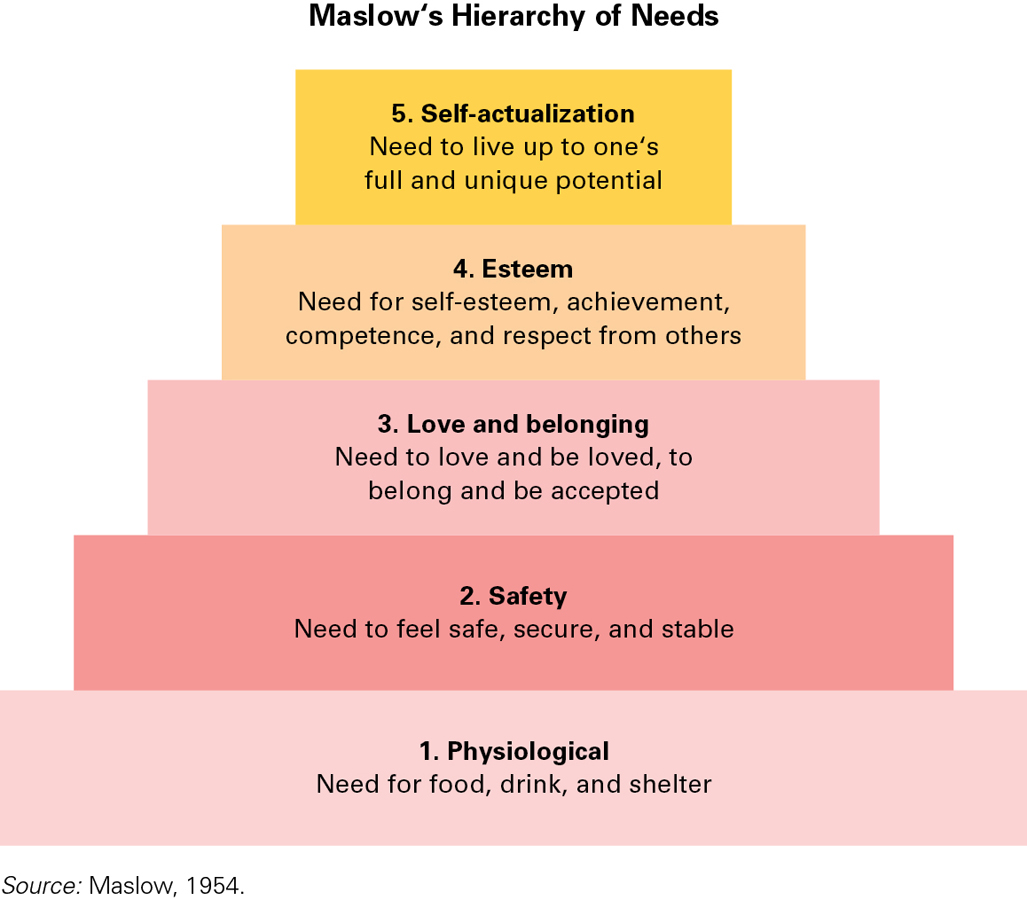

Many scientists are convinced that there is something hopeful, unifying, and noble in the human spirit, something ignored by psychoanalytic theory and behaviourism. The limits of those two major theories were especially apparent to Abraham Maslow (1908–

33

- Physiological: needing food, water, warmth, and air

- Safety: feeling protected from injury and death

- Love and belonging: having loving friends, family, and a community

- Esteem: being respected by the wider community as well as by oneself

- Self-

actualization: becoming truly oneself, fulfilling one’s unique potential.

At self-

Maslow contended that everyone must satisfy each lower level before moving higher. A starving man, for instance, may risk his life to secure food (level 1 precedes level 2), or an unloved woman might not care about self-

Although humanism does not postulate stages, a developmental application of this theory is that satisfying childhood needs is crucial for later self-

This theory is prominent among medical professionals because they realize that pain can be physical (the first two levels) or social (the next two) (Majercsik, 2005; Zalenski & Raspa, 2006). Even the very sick need love and belonging (family should be with them) and esteem (the dying need respect).

Evolutionary Theory

Charles Darwin’s basic ideas about evolution were first published 150 years ago (Darwin, 1859), but serious research on human development inspired by evolutionary theory is quite recent (Gangestad & Simpson, 2007).

According to this theory, nature works to ensure that each species does two things: survive and reproduce. Consequently, many human impulses, needs, and behaviours evolved to help humans survive and thrive over 100 000 years (Konner, 2010). Evolutionary theory has intriguing explanations for many phenomena in human development, including women’s nausea in pregnancy, 1-

To understand human development, this theory contends, humans need to recognize what was adaptive thousands of years ago. For example, it is irrational that many people are terrified of snakes (which cause 1 death in a billion), but virtually no one fears automobiles (which cause about 1 death in 5000). Evolutionary theory suggests that the fear instinct evolved to protect life when snakes killed many people, which was true until quite recent history. Our fears have not caught up to modern life.

Some of the best human qualities, such as cooperation, spirituality, and self-

34

KEY Points

- Developmental theories provide a crucial framework, enabling people to understand and study life.

- Psychoanalytic theory posits stages of development. Freud emphasized unconscious urges; Erikson stressed eight stages of psychosocial development, from infancy through old age.

- Learning theory focuses on the fact that people’s behaviours are influenced by their social environment. Two learning theories are behaviourism and social learning theory. Behaviourism contends that people have learned most of what they do either through association or reinforcement. Social learning theory states that individuals can learn by observation and modelling.

- Cognitive theory stresses that the way people think affects their behaviour. Piaget’s stages are one example.

- Systems theory emphasizes that human development takes place within the context of some type of system, a complex set of relationships in which each part is related to and affected by every other part. Family systems theory focuses on the interrelationships of family members and how one individual affects the others.

- Humanism recognizes universal human needs that must be met for people to reach the highest level, self-

actualization, thereby becoming the best they can be. - Evolutionary theory explains emotions and actions on the basis of their contribution to survival and reproduction in past millennia.