2.3 Problems and Solutions

The early days of prenatal life place the developing person on a path toward health and success—

From the moment of conception to the days and months after birth, many biological and psychological factors protect each new life. We now look at specific problems that may occur and how to prevent or minimize them. Always remember dynamic systems—

71

Abnormal Genes and Chromosomes

Perhaps half of all zygotes have serious abnormalities of their chromosomes or genes. Most of them never grow or implant—

Chromosomal MiscountsAbout once in every 200 births, an infant is born with 45, 47, or even 48 or 49 chromosomes instead of the usual 46. Each of these produces a recognizable syndrome, a cluster of distinct characteristics that occur together. The variable that most often correlates with an odd number of chromosomes is the age of the mother, presumably because her ova become increasingly fragile by midlife. The father’s age is also relevant, again probably because his gametes become less robust with age (Brenner et al., 2009).

The most common extra-

Another common problem occurs at the 23rd pair of chromosomes. Not every person has two, and only two, sex chromosomes. About 1 in every 500 infants is born with only one sex chromosome (no Y) or with three or more (not just two) (Hamerton & Evans, 2005). Such children have many challenges, especially in sexual maturation and fertility. The specifics depend on the particular configuration as well as on other genetic factors (Mazzocco & Ross, 2007).

72

Gene DisordersEveryone is a carrier of genes or alleles that could produce serious diseases or disabilities in the next generation. Given that most disorders are polygenic and that the mapping of the human genome is recent, the exact impact of each allele is not yet known (Couzin-

Most of the 7000 known single-

If the condition is fatal in childhood, it will, of course, never be transmitted. Thus, all common dominant disorders either begin in adulthood (Huntington disease and early-

One disorder once thought to be dominant is Tourette syndrome, which may make a person have uncontrollable tics and explosive verbal outbursts. But most people with Tourette syndrome have milder symptoms, such as an occasional twitch or a controllable impulse to speak inappropriately. Recent research finds a complex inheritance: probably multiple genes and epigenetic factors rather than a single dominant gene (Woods et al., 2007).

The number of recessive disorders is probably in the millions, most of them rare. For example, Canadian writer Ian Brown’s son Walker was born with a genetic disorder so rare it occurs only once in every 300 000 births. The resulting syndrome creates very serious developmental difficulties. The Boy in the Moon, Brown’s 2009 account of Walker’s birth and development, gives a moving description of what it is like to live with (and to love) a child who is severely disabled:

Tonight I wake up in the dark to a steady, motorized noise. Something wrong with the water heater. Nnngah. Pause. Nnngah. Nnngah.

But it’s not the water heater. It’s my boy, Walker, grunting as he punches himself in the head, again and again.

He has done this since before he was two. He was born with an impossibly rare genetic mutation, cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome, a technical name for a mash of symptoms. He is globally delayed and can’t speak, so I never know what’s wrong. No one does. There are just over a hundred people with CFC around the world. The disorder turns up randomly, a misfire that has no certain cause or roots; doctors call it an orphan syndrome because it seems to come from nowhere.

[Brown, 2009]

Other recessive conditions are much more common, including cystic fibrosis, thalassemia, and sickle-

| Method | Description | Risks, Concerns, and Indications |

|---|---|---|

| Preconception blood tests | Test for nutrients (especially iron); for diseases (syphilis, HIV, herpes, hepatitis B); for carrier status (cystic fibrosis, sickle- |

Might require postponement of pregnancy for counselling, treatment. |

| Pre- |

After in vitro fertilization, one cell is removed from each zygote at the four- |

Not entirely accurate; requires in vitro fertilization and rapid assessment, delaying implantation. Used when couples are at high risk of known, testable disorders. |

| Tests for pregnancy- |

Blood tests are usually done at about 11 weeks to indicate levels of these substances. | Low levels correlate with chromosomal miscounts and slow prenatal growth, but falsepositive or false- |

| Alpha- |

Blood is tested for alpha- |

High AFP indicates neural- |

| Sonogram (ultrasound) | High- |

Reveals head or body malformations, excess brain fluid, Down syndrome (via fetal neck measurement), and several diseases. Estimates fetal age and growth, reveals multiple fetuses and placental position. No known risks, unlike the X- |

| Chorionic villus sampling (CVS) | A sample of the chorion (part of the placenta) obtained (via sonogram and syringe) at 10 weeks and analyzed. Cells of placenta are genetically identical to fetal cells, so CVS indicates genetic conditions. | Can cause spontaneous abortion (rare). |

| Amniocentesis | Some fluid inside the placenta is withdrawn (via sonogram and syringe) at 16 weeks; cells cultured and analyzed. | Can cause spontaneous abortion (rare). Detects abnormalities later in pregnancy than other tests but is very accurate. |

| *Many newer tests are experimental, soon to be offered to the general public. Therefore, this list is partial, to illustrate that many tests are used at various times during pregnancy to indicate possible problems. | ||

Teratogens

Possible problems can occur after conception as well, because many toxic substances, illnesses, and experiences can harm a fetus. Every week scientists discover an unexpected teratogen, which is anything—

73

Some teratogens cause no physical defects but affect the brain, making a child hyperactive or antisocial, or resulting in the child having a learning disability. These are behavioural teratogens. About 20 percent of all children have difficulties that could be connected to behavioural teratogens, although the link is not straightforward: The cascade is murky, in part because the impact of the environment varies (Bell & Robinson, 2011).

One of my students described her little brother as follows:

I was nine years old when my mother announced she was pregnant. I was the one who was most excited.…My mother was a heavy smoker, Colt 45 beer drinker.…I asked, “Why are you doing it?” She said, “I don’t know.”

During this time I was in the fifth grade and we saw a film about birth defects. My biggest fear was that my mother was going to give birth to an infant with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS)… My baby brother was born right on schedule. The doctors claimed a healthy newborn… Once I heard healthy, I thought everything was going to be fine. I was wrong, then again I was just a child.…My baby brother never showed any interest in toys…he just cannot get the right words out of his mouth…he has no common sense. …

[J., personal communication]

74

My student wrote: “Why hurt those who cannot defend themselves?” J. blames her mother for drinking beer, although genes, postnatal experiences, and the lack of information and services that could have prevented harm (for instance, some drug rehab programs do not accept pregnant women) may have contributed to her brother’s lack of “common sense.” Just as every teratogen can be mitigated by other circumstances, every one can be made worse. An understanding of risk is crucial.

Risk Analysis

Risk analysis discerns which chances are worth taking and how risks are minimized. Let’s pick an easy example: Crossing the street is a risk, yet it would be worse to avoid all street crossing. Knowing this, we cross carefully, looking both ways.

Although all teratogens increase the risk of harm, none always causes damage. The impact of teratogens depends on the interplay of many factors, both destructive and protective, an example of the dynamic-

75

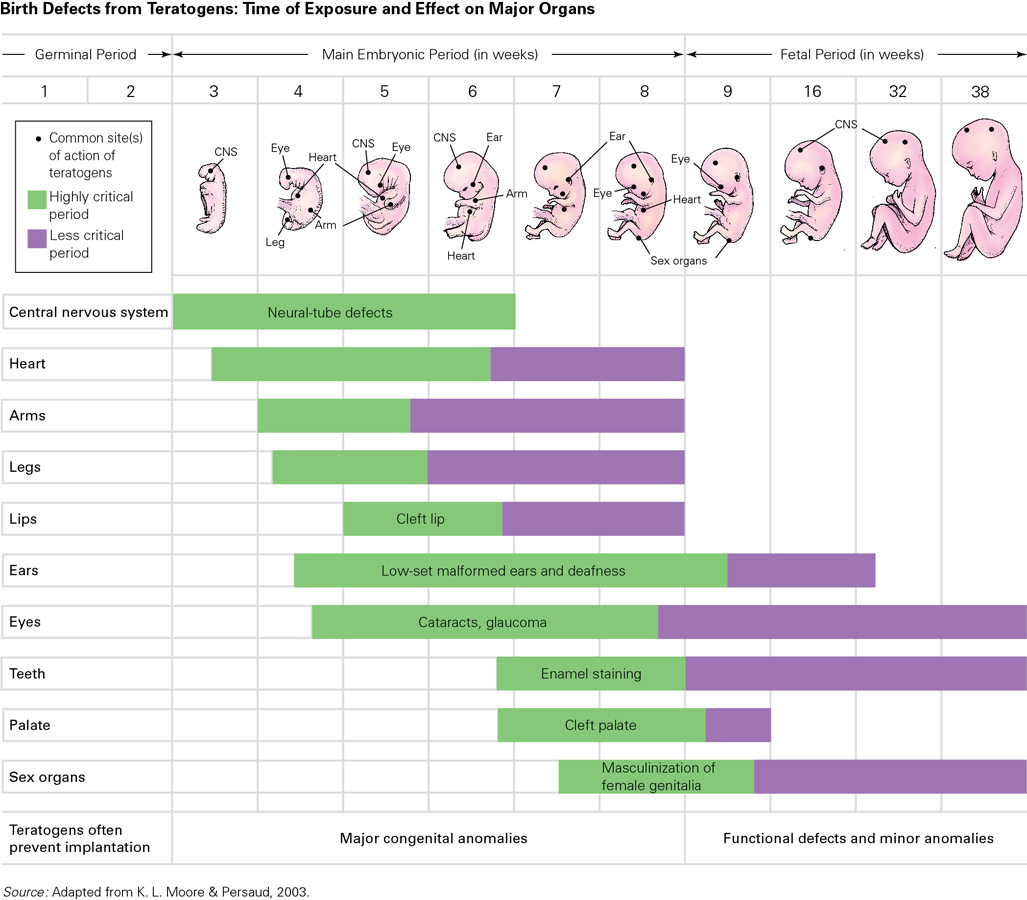

The Critical TimeOne crucial factor in the effect of a teratogen is timing—the age of the developing embryo or fetus when it is exposed to the teratogen (Sadler, 2012). Some teratogens cause damage only during a critical period (see Chapter 1) (see Figure 2.9).

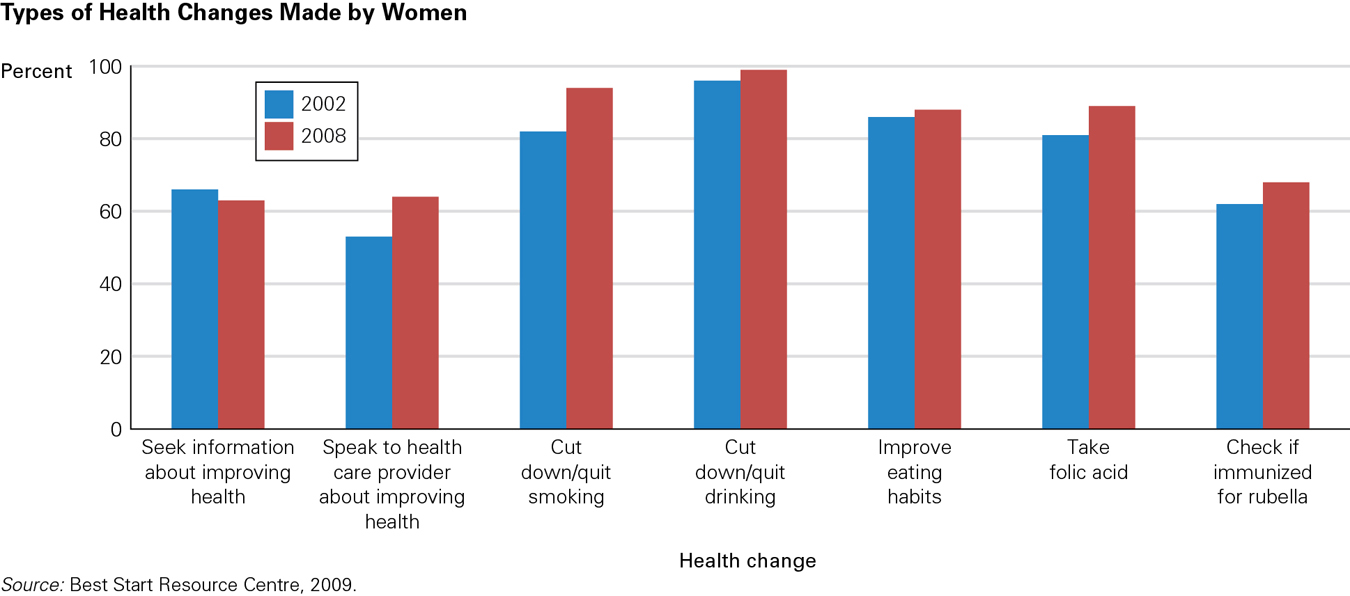

Obstetricians recommend that before pregnancy occurs, women should avoid drugs (especially alcohol), supplement a balanced diet with extra folic acid and iron, and update their immunizations. Indeed, preconception health is at least as important as health during pregnancy.

In recent years, Canadian women have been more active and aware of the importance of preconception health as a strategy to optimize a healthy birth. Through public awareness campaigns, discussions with health care providers, and preconception classes, expectant mothers and fathers have gained the knowledge, skills, motivation, opportunity, access, and supportive environments that make it easier to engage in healthy behaviours (McGreary, 2007). (See Figure 2.10 for examples of changes in prenatal health behaviours.)

The first days and weeks after conception (the germinal and embryonic periods) are critical for body formation, but the entire fetal period is a sensitive time for brain development. Further, preterm birth is a risk factor that is affected by nutrition and drugs throughout pregnancy.

Timing may be important even before conception. When pregnancy occurs soon after a previous pregnancy, risk increases, perhaps because a woman’s body may need time to recover from birth. For example, second-

The critical and sensitive period concepts are helpful in understanding cerebral palsy (difficulties with movement control resulting from brain damage), which was once thought to be caused solely by birth procedures (excessive medication, slow breech birth, or use of forceps to pull the fetal head through the birth canal). We now know that cerebral palsy results from genetic vulnerability, teratogens, and maternal infection (J. R. Mann et al., 2009), and not only insufficient oxygen to the fetal brain at birth.

76

A lack of oxygen is anoxia, which often occurs for a second or two during birth, indicated by a slower fetal heart rate. To prevent prolonged anoxia, the fetal heart rate is monitored during labour. Avoiding anoxia is also the reason that two of the five Apgar ratings indicate oxygen level. How long anoxia can continue without harming the brain depends on genes, birth weight, gestational age (preterm newborns are more vulnerable), drugs (either taken by the mother before birth or given during birth), and many other factors. Insufficient oxygen may begin long before birth. Thus, anoxia is part of a cascade that may cause cerebral palsy or other problems. Inadequate oxygen during pregnancy is a serious condition, which is why listening to the fetal heartbeat is part of every prenatal visit.

How Much is Too Much?A second factor affecting the harm from any teratogen is the dose and/or frequency of exposure. Some teratogens have a threshold effect; they are virtually harmless until exposure reaches a certain level, at which point they “cross the threshold” and become damaging. This threshold is not a fixed boundary: Dose, timing, frequency, and other teratogens affect when the threshold is crossed (O’Leary et al., 2010).

Thresholds are difficult to set because one teratogen may increase the harm from another. Consider alcohol. Early in pregnancy, an embryo exposed to heavy drinking can develop fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which distorts the facial features (especially the eyes, ears, and upper lip). Later in pregnancy, alcohol is a behavioural teratogen, the cause of fetal alcohol effects (FAE), leading to hyperactivity, poor concentration, impaired spatial reasoning, and slow learning (Niccols, 2007; Streissguth & Connor, 2001). Health Canada (2005) estimates that the Canada-

Currently, Health Canada advises all Canadian women who are pregnant or even thinking of becoming pregnant to avoid taking any alcohol whatsoever: “STOP drinking alcohol now if you are planning to become pregnant” (Health Canada, 2005). By contrast, women in the United Kingdom receive conflicting advice about drinking an occasional glass of wine (Raymond et al., 2009), and French women are told to abstain, but many have not heard that message (Toutain, 2010). Total abstinence requires that all women who might become pregnant avoid a legal substance that most adults use routinely. Wise? Probably. Necessary? Maybe not.

ESPECIALLY FOR Judges and Juries How much protection, if any, should the legal system provide for fetuses? Should alcoholic women who are pregnant be jailed to prevent them from drinking? What about people who enable them to drink, such as their partners, their parents, bar owners, bartenders?

The law punishes women who jeopardize the health of their fetuses, but a developmental view would consider the micro-, exo-, and macrosystems.

Genetic VulnerabilityGenes are a third factor that influences every aspect of conception, pregnancy, and birth. Consider what happens when a woman carrying dizygotic twins drinks alcohol, for example. The alcohol in the mother’s blood stream reaches the placenta and then the embryos via the umbilical cord. Thus, the twins’ blood alcohol levels are equal. However, one twin may be more severely affected than the other because their alleles for the enzyme that metabolizes alcohol may differ.

Genetic vulnerability is a particular example of differential susceptibility, as described in Chapter 1. Genetic protections or hazards are suspected for many birth defects (Sadler, 2012). A protective factor seems to be the X chromosome; male fetuses (only one X) are more vulnerable to teratogens than females (XX) (Lewis & Kestler, 2012).

77

Since fathers provide 23 chromosomes, they are as likely as mothers to provide genetic protection or vulnerability. Maternal genes have an additional role: They affect a mother’s body and thus the environment of the womb. One maternal allele results in low levels of folic acid during pregnancy. Via the umbilical cord, this can produce neural-

Neural-

In 1998, both Canada and the United States created laws that required folic acid to be added to packaged cereal products such as white flour, enriched pasta, and cornmeal. The aim of these measures is to protect every woman, even if she does not expect to become pregnant. A Canadian study found that the rate of neural-

Applying the ResearchRisk analysis cannot precisely predict the results of genetic vulnerability, teratogenic exposure, or birth complications in individual cases. However, much is known about what individuals and society can do to reduce the risks. TABLE 2.6 lists some teratogens and their possible effects, as well as preventive measures.

| Teratogens | Effects of Exposure on Fetus | Measures for Preventing Damage |

|---|---|---|

| Diseases | ||

| Rubella (German measles) | In embryonic period, causes blindness and deafness; in first and second trimesters, causes brain damage. | Get immunized before becoming pregnant. |

| Toxoplasmosis | Brain damage, loss of vision, intellectual disabilities. | Avoid eating undercooked meat and handling cat feces, garden dirt during pregnancy. |

| Measles, chicken pox, influenza | May impair brain functioning. | Get immunized before getting pregnant; avoid infected people during pregnancy. |

| Syphilis | Baby is born with syphilis, which, untreated, leads to brain and bone damage and eventual death. | Early prenatal diagnosis and treatment with antibiotics. |

| AIDS | Baby may catch the virus. Without treatment, illness and death are likely during childhood. | Prenatal drugs and Caesarean birth make AIDS transmission rare. |

| Other sexually transmitted infections, including gonorrhea and chlamydia | Not usually harmful during pregnancy but may cause blindness and infections if transmitted during birth. | Early diagnosis and treatment; if necessary, Caesarean section, treatment of newborn. |

| Infections, including infections of urinary tract, gums, and teeth | May cause premature labour, which increases vulnerability to brain damage. | Get infection treated, preferably before becoming pregnant. |

| Pollutants | ||

| Lead, mercury, PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls); dioxin; and some pesticides, herbicides, and cleaning compounds | May cause spontaneous abortion, preterm labour, and brain damage. | Most common substances are harmless in small doses, but pregnant women should avoid regular and direct exposure, such as drinking well water, eating unwashed fruits or vegetables, using chemical compounds, and eating fish from polluted waters. |

| Radiation | ||

| Massive or repeated exposure to radiation, as in medical X- |

In the embryonic period, may cause abnormally small head (microcephaly) and intellectual disabilities; in the fetal period, suspected but not proven to cause brain damage. Exposure to background radiation, as from power plants, is usually too low to have an effect. | Get sonograms, not X- |

| Social and Behavioural Factors | ||

| Very high stress | Early in pregnancy, may cause cleft lip or cleft palate, spontaneous abortion, or preterm labour. | Get adequate relaxation, rest, and sleep; reduce hours of employment; get help with housework and child care. |

| Malnutrition | When severe, may interfere with conception, implantation, normal fetal development, and full- |

Eat a balanced diet (with adequate vitamins and minerals, including, especially, folic acid, iron, and vitamin A); achieve normal weight before getting pregnant, then gain 10– |

| Excessive, exhausting exercise | Can affect fetal development when it interferes with pregnant woman’s sleep, digestion, or nutrition. | Get regular, moderate exercise. |

| Medicinal Drugs | ||

| Lithium Tetracycline Retinoic acid Streptomycin ACE inhibitors Phenobarbital Thalidomide |

Can cause heart abnormalities. Can harm teeth. Can cause limb deformities. Can cause deafness. Can harm digestive organs. Can affect brain development. Can stop ear and limb formation. |

Avoid all medicines, whether prescription or over- |

| Psychoactive Drugs | ||

| Caffeine | Normal use poses no problem. | Avoid excessive use: Drink no more than three cups a day of beverages containing caffeine (coffee, tea, cola drinks, hot chocolate). |

| Alcohol | May cause fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) or fetal alcohol effects (FAE). | Stop or severely limit alcohol consumption during pregnancy; especially dangerous are three or more drinks a day or four or more drinks on one occasion. |

| Tobacco | Reduces birth weight, increases risk of malformations of limbs and urinary tract, and may affect the baby’s lungs. | Stop smoking before becoming pregnant; if already pregnant, stop smoking immediately. |

| Marijuana | Heavy exposure may affect the central nervous system; when smoked, may hinder fetal growth. | Avoid or strictly limit marijuana consumption. |

| Heroin | Slows fetal growth and may cause premature labour; newborns with heroin in their bloodstream require medical treatment to prevent the pain and convulsions of withdrawal. | Get treated for heroin addiction before becoming pregnant; if already pregnant, gradual withdrawal on methadone is better than continued use of heroin. |

| Cocaine | May cause slow fetal growth, premature labour, and learning problems in the first years of life. | Stop using cocaine before pregnancy; babies of cocaine- |

| Inhaled solvents (glue or aerosol) | May cause abnormally small head, crossed eyes, and other indications of brain damage. | Stop sniffing inhalants before becoming pregnant; be aware that serious damage can occur before a woman knows she is pregnant. |

| Sources: Gupta, 2011; Mann & Andrews, 2007; O’Rahilly & Müller, 2001; Reece & Hobbins, 2007; Sadler, 2012; Shepard & Lemire, 2004. | ||

| * The field of toxicology advances daily. Research on new substances begins with their effects on nonhuman species, which provides suggestive (though not conclusive) evidence. This table is a primer; it is no substitute for careful consultation with a professional who knows the recent research. | ||

Remember that the outcomes vary. Many fetuses are exposed with no evident harm. The opposite occurs as well: About 20 percent of all serious defects occur for reasons unknown. Women are advised to maintain good nutrition and avoid teratogens, especially drugs and chemicals (pesticides, cleaning fluids, and many cosmetics contain teratogenic chemicals). Some medications are necessary (e.g., for women who have epilepsy, diabetes, severe depression) and should be continued, but caution should begin before pregnancy is confirmed.

Sadly, the cascade of teratogens is most likely to begin with women who are already vulnerable. For example, cigarette smokers are more often drinkers (as was J.’s mother); those whose jobs involve chemicals and pesticides are more often malnourished; low-

The benefits of early prenatal care are many: Women can be told which substances to avoid, they can learn what to eat and what to do, and they may be diagnosed and treated for some conditions (syphilis and HIV among them) that harm the fetus only if early treatment does not occur. As noted earlier, prenatal tests (of blood, urine, and fetal heart rate, as well as ultrasound) and even preconception tests can identify many disorders (see TABLE 2.5). When complications (such as twins, gestational diabetes, infections) arise, early recognition increases the chance of a healthy birth.

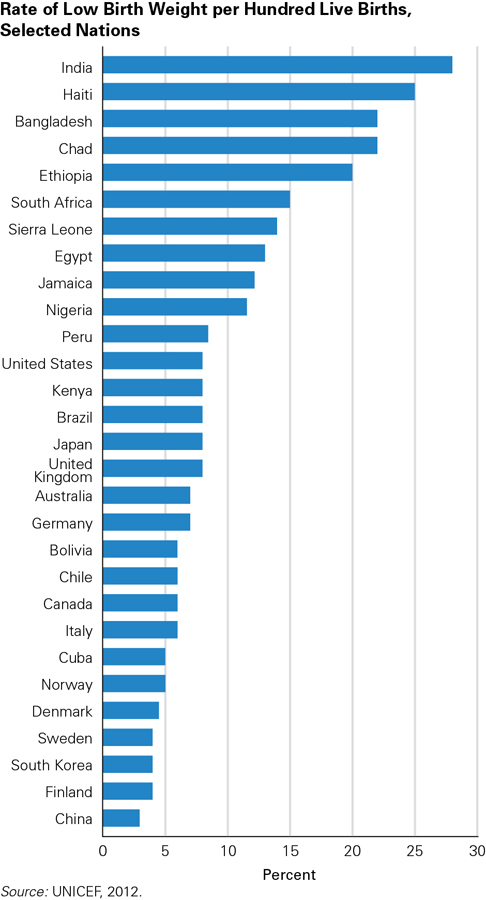

One obvious effect of early prenatal care is that the risk of low birth weight is reduced. As you will now see, an underweight newborn is vulnerable in dozens of ways. Indeed, the United States’ rate of infant death is higher than many other nations largely because of more underweight babies. In Canada, the rate of infant death is also higher than for many industrialized countries, but the reasons for this are complex, as you will see in the feature A View from Science: Why Are Infant Mortality Rates in Canada So High?.

78

79

Low Birth Weight

Some newborns, especially preterm babies, are small and immature. With modern hospital care, tiny infants usually survive, but it would be better for everyone—

Low birth weight (LBW) is defined by the World Health Organization as weight under 2500 grams. LBW babies are further grouped into very low birth weight (VLBW), under 1500 grams, and extremely low birth weight (ELBW), under 1000 grams.

Recently, some researchers have examined the issue of birth weight by taking ethnicity into consideration. One Canadian study noted that babies of immigrant mothers from regions of the world other than Europe and North America are often smaller than those of domestically born mothers. Some of these smaller babies run the risk of being classified LBW and subjected to unnecessary tests and hospitalizations when actually they are a normal weight for newborns from their world region. The researchers concluded that “birthweight curves [standards] need to be modified for newborns of immigrant mothers originating from non-

80

Maternal BehaviourFetal weight normally doubles in the last three months of a full term pregnancy, with 900 grams of that gain occurring in the final three weeks. Thus, a baby born preterm (three or more weeks early; no longer called premature) is usually LBW.

Preterm birth correlates with many of the teratogens already mentioned, an example of the cascade that leads to newborns with evident problems. The prenatal environment itself may cause early labour as well. Indeed, when the environment of the womb is harmful, as when multiple fetuses reduce nourishment to each individual fetus, hormones can precipitate labour.

Early birth is only one cause of low birth weight. Some fetuses gain weight slowly throughout pregnancy and are small for gestational age (SGA) (also called small-

Another common reason for slow fetal growth is maternal malnutrition. Women who begin pregnancy underweight, who eat poorly during pregnancy, or who gain less than 1.3 kilograms per month in the final six months are likely to have an underweight infant. Malnutrition (not age) is the primary reason teenagers often have small babies. Unfortunately, many of the risk factors just mentioned—

Fathers and Significant OthersThe causes just mentioned of low birth weight focus on the pregnant woman: If she takes drugs or is undernourished, her fetus suffers. Conversely, if she take cares to nourish herself, to not take drugs, and to avoid exhaustion, she can help protect the baby’s prenatal health. However, the more we learn about birth problems, the more important fathers—

Much Canadian research over the last two decades bears out the idea that fathers have strong impacts on the health and well-

Although there are no clear reasons why teenage fathers might contribute to an increased rate of negative birth outcomes, the researchers speculated about several causes. First, biology itself might play a role, since younger men tend to have more immature sperm, which lead to “abnormal placentation,” or difficulties in implanting properly in the nourishing environment of the placenta.

Second, socioeconomic factors may have an influence, since teenage fathers often come from economically disadvantaged families and have less education than older fathers. Parents from disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to make use of prenatal care services, which leads to a greater risk of poor birth outcomes. Also the social dynamics between teenage parents may have negative consequences for newborns, since men of this age tend to be more prone to violence and have fewer financial resources to support their spouses than older men have.

Finally, lifestyle factors can play a role, because drinking, smoking, and the use of illegal drugs, which are all more common with teenage fathers, can lead to adverse birth outcomes (Chen et al., 2007).

81

Consequences of Low Birth WeightEarly death is the most obvious hazard of low birth weight. But problems do not end with survival. When compared with newborns conceived at the same time but born later, very low-

As months go by, cognitive, visual, and hearing impairments emerge. High-

Longitudinal research studies find that, compared with the average child in middle childhood, formerly SGA children have smaller brain volume, and those who were preterm have lower IQs (van Soelen et al., 2010). Even in adulthood, risks persist: Adults who were LBW are more likely to have heart disease and diabetes.

However, remember that risk analysis gives odds, not certainties—

Comparing NationsThe low-

What factors other than being born preterm may affect the baby’s birth weight? Historically, personal factors such as smoking, alcohol and drug use, poor nutrition before and during pregnancy, and high stress have put a mother at risk for a low birth weight baby. Key environmental factors have been poverty, single or teenage parenthood, and living with a violent partner.

82

However, according to a 2009 report from Vital Signs Canada (VSC), some factors that have historically contributed to low birth weight are declining across the country, including smoking among pregnant women and incidence of teenage pregnancy (VSC, 2009). Other factors, such as the increasing number of older women (aged 35–

As for the United States, the Department of Agriculture found an increase in food insecurity (measured by skipped meals, use of food stamps, and outright hunger) in the past decade. Food insecurity directly affects LBW, and it also increases chronic illness, which itself correlates with LBW (Seligman & Schillinger, 2010). In 2008, about 15 percent of U.S. households were considered food insecure, with rates higher among women in their prime reproductive years than among middle-

Worldwide, far fewer low-

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Why Are Infant Mortality Rates So High in Canada?

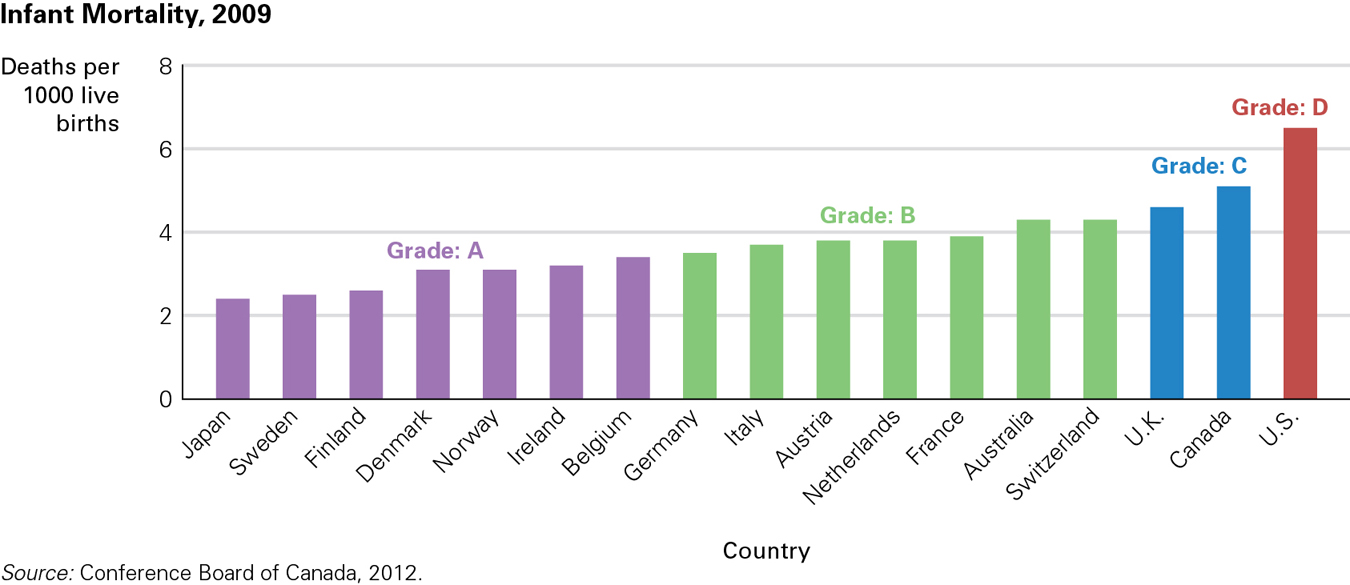

The infant mortality rate (IMR) is defined as the number of deaths that occur before a child’s first birthday per 1000 live births. Tracking this rate is important because it acts as an indicator of children’s health and well-

Given the importance of the IMR, the question becomes how well is Canada performing compared with other nations? Apparently rather poorly, according to the OECD report just mentioned. In ranking 17 industrialized nations, the OECD placed Canada second to last, with an IMR of 5.1, ahead of only the United States (see Figure 2.12). This result led the Conference Board of Canada to call Canada’s IMR “shockingly high for a country at Canada’s level of socioeconomic development” André Lalonde, vicepresident of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, lamented, “We’re losing our reputation. We have fallen way behind” (Priest, 2010).

Thanks to medical advances, between 1960 and 1980 Canada’s IMR did drop significantly, from 27 deaths per 1000 live births to 10. After 1980, the rate continued to improve but not in as dramatic a fashion. After 2000, it stabilized to between 5.5 and 5.0 but stubbornly resisted all attempts to push it below the 5.0 mark. Nonetheless, since the 1960s, many other industrialized countries have improved at greater speed and have achieved lower rates. For example, Japan’s 2009 IMR was 2.6, just about half that of Canada’s.

To some extent, relatively high IMR in Canada may stem from the way “live birth” is defined across nations. For instance, Canadian officials define a live birth as a newborn that takes a breath or shows other signs of life (Statistics Canada, 2011a). In contrast, both France and the Netherlands define a live birth as a baby who meets the minimal weight of 2500 grams or 22 weeks gestation (EURO-

Other researchers have suggested that the higher Canadian rates are due in part to the prevalence of new technologies for delivering preterm or VLBW babies (Milan, 2011). Thus, many more babies are given a greater chance of living who may have been stillborn in years past. Since they are so fragile, however, a number of them die in infancy. New fertility programs also lead to multiple births, and since these babies tend to be born preterm, they are at a higher risk of early death (Conference Board of Canada, 2012).

83

Researchers also recognize that there are important environmental or socioeconomic factors that contribute to Canada’s high IMR. These include the growing gap between rich and poor and high rates of child poverty and teen pregnancies (Warick, 2010; Raphael, 2010). Another factor that can have an effect is isolation, as with remote villages in rural regions where quality health care can be difficult to access and where poor water quality and substandard housing are persistent concerns.

All of these environmental factors have particular relevance for Aboriginal peoples in Canada. According to most researchers, the IMR among First Nations is twice as high as that for the general population, while the rate for Inuit communities is three to four times higher (Smylie et al., 2010). Federal government initiatives to lower the IMR, especially in Aboriginal communities, include the Maternal Child Health Program, the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program, Aboriginal Head Start, and Early Childhood Development programs (Native Women’s Association of Canada, 2012).

Thanks in part to these and other initiatives, in 2009 Canada’s IMR finally cracked the 5.0 barrier and registered at 4.9. However, by current measure, Canada’s IMR is still significantly higher than that of most other industrialized countries.

KEY Points

- Zygotes with abnormal chromosomes and genes are common: Most are spontaneously aborted early after conception. Survivors (e.g., those with Down syndrome) benefit from good care.

- Although hundreds of teratogens can harm the fetus, many future babies are protected by genes, timing (late), dose (small), and frequency (rare).

- Fathers, future grandparents, and cultures reduce risks, making sure expectant mothers are well fed, rested, and drug-

free. - Newborns born early and small for gestational age are at risk for many problems, at birth and throughout the life span.

- Infant mortality rates in Canada are considered high when compared with rates in other countries.

84