92

| THE FIRST TWO YEARS: |

| Body and Mind |

|

|

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Growth in Infancy

Body Size

Brain Development

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE: Face Recognition

Sleep

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES: Where Should Babies Sleep?

Perceiving and Moving

The Senses

Motor Skills

Dynamic Sensory-

Surviving in Good Health

Better Days Ahead

Immunization

Nutrition

Infant Cognition

Sensorimotor Intelligence

Information Processing

Language

The Universal Sequence

Cultural Differences

How Do They Do It?

93

WHAT WILL YOU KNOW?

- What part of an infant grows most in the first two years?

- How are newborn humans the opposite of newborn kittens?

- Does immunization protect or harm babies?

- If a baby doesn’t look for an object that disappears, what does that mean?

- Why talk to babies who are too young to understand words?

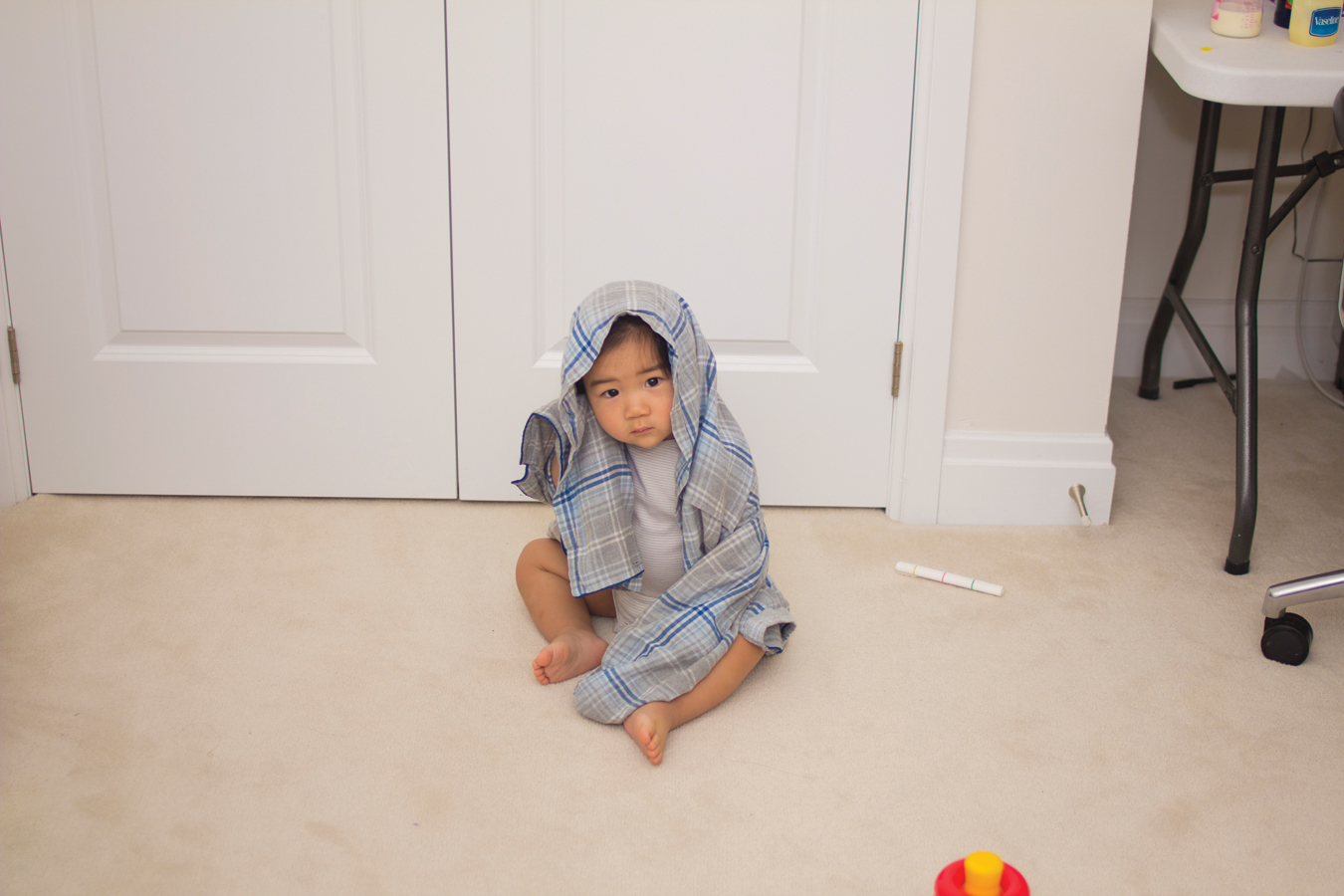

Our first child, Bethany, was born when I was in graduate school. I studiously memorized developmental norms, including sitting at 6 months, and walking and talking at 12. But although Bethany had not yet taken her first step at 14 months, I was not worried. I told my husband that genes were more influential than anything we did. I had read that babies in Paris are among the latest walkers in the world, and my grandmother was French. My speculation was bolstered when our next two children, Rachel and Elissa, were also slow to walk.

Fourteen years after Bethany, Sarah was born. I could afford a fulltime caregiver, Mrs. Todd. She thought Sarah was the most advanced baby she had ever known, except for her own daughter, Gillian. I told her that Berger children walk late.

“She’ll be walking by a year,” Mrs. Todd told me. “Gillian walked at 10 months.”

“We’ll see,” I graciously replied, confident of my genetic explanation.

Mrs. Todd bounced my delighted baby on her lap, day after day, and spent hours giving her “walking practice.” Sarah’s first step was at 12 months, late for a Todd, early for a Berger, and a humbling lesson for me. ·

—Kathleen Berger

94

AS A SCIENTIST, I KNOW THAT A SINGLE case proves nothing. Sarah shares only half her genes with Bethany. My daughters are only one-

Nonetheless, as you read about development, remember that caregiving enables babies to grow, move, and learn. Development is not as straightforward and automatic, nor as genetically determined, as it once seemed. It is multidirectional, multi-