3.1 Growth in Infancy

In infancy, growth is so rapid and the consequences of neglect are so severe that gains are closely monitored. Medical checkups, including measurements of height, weight, and head circumference, occur often in developed nations because these measurements provide the first clues as to whether an infant is progressing as expected—

Body Size

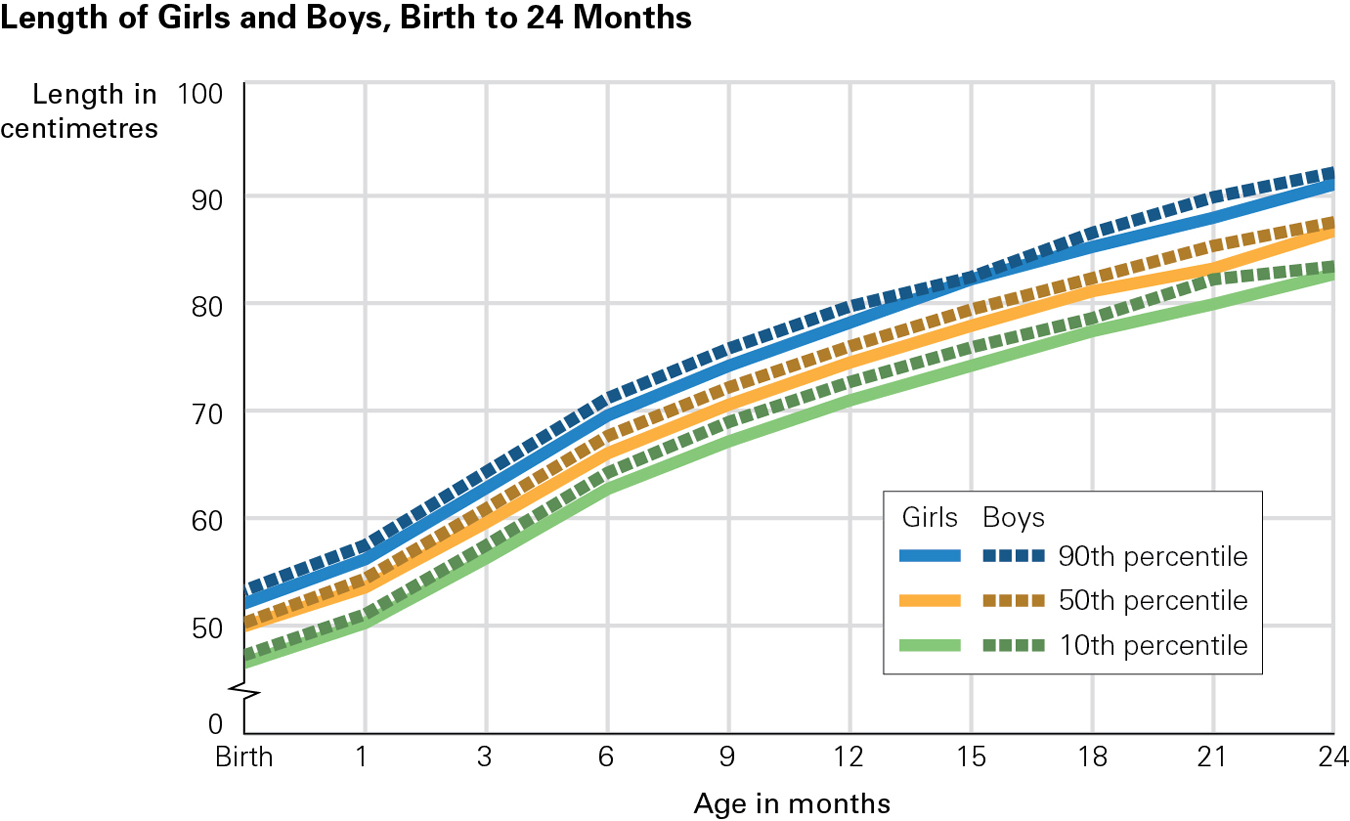

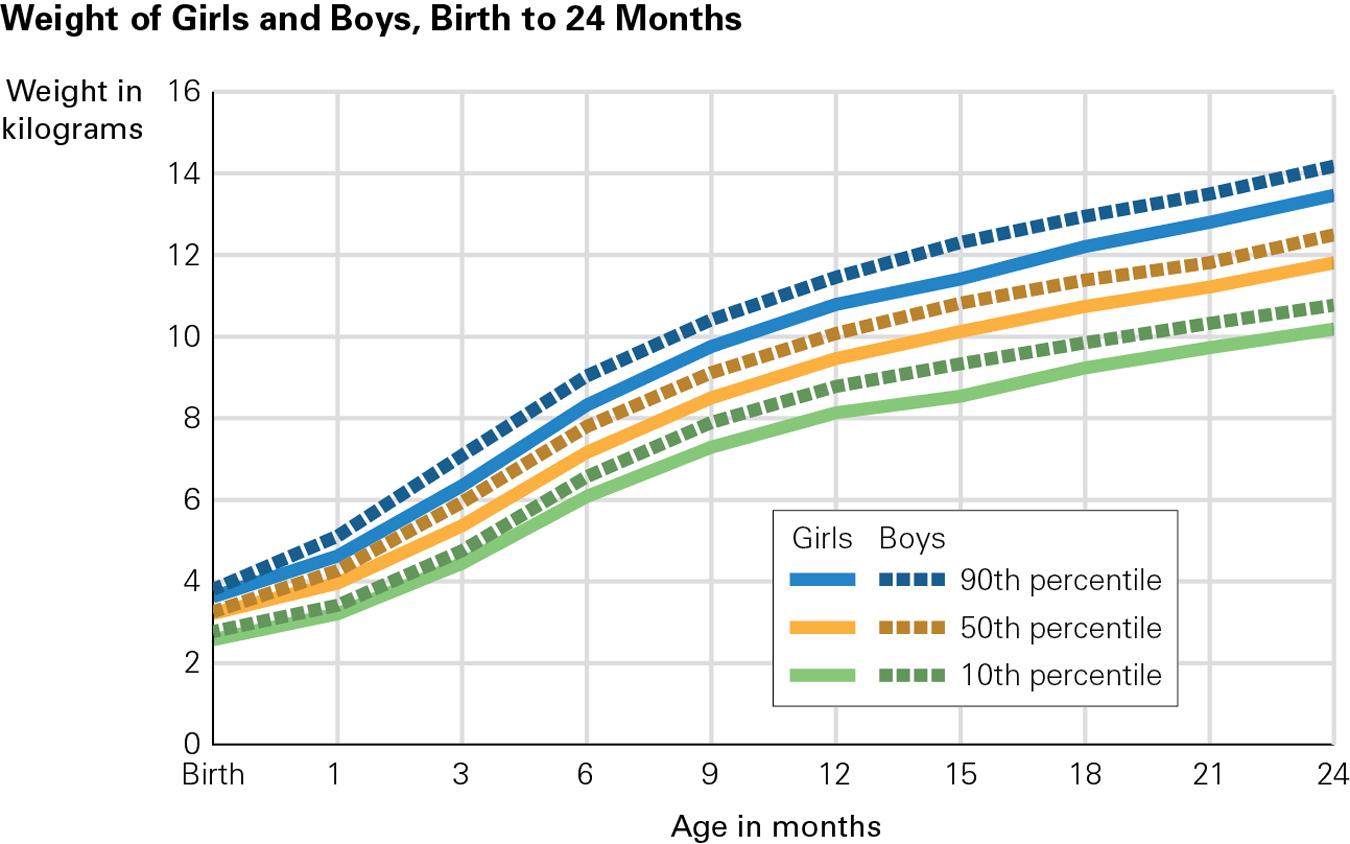

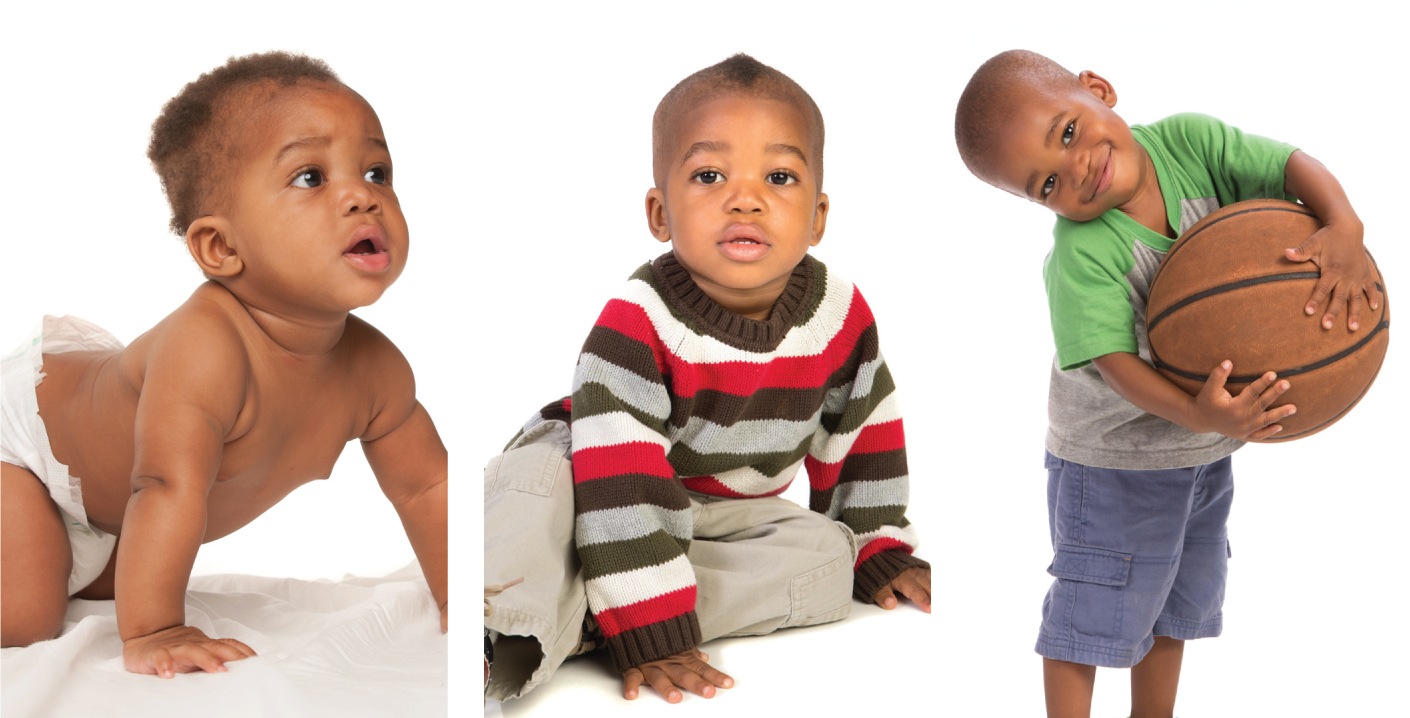

Weight gain is dramatic. Newborns lose a bit of weight in the first three days of life and then gain about 30 grams a day for several months. Birth weight typically doubles by 4 months and triples by a year. A typical 3175-

Physical growth in the second year is slower but still rapid. By 24 months, most children weigh almost 13 kilograms. They have added more than 30 centimetres in height—

Each of these numbers is a norm, which is an average, or standard, for a particular population. The “particular population” for the norms just cited is North American infants. Remember, however, that genetic diversity means that some perfectly healthy newborns are smaller or larger than these norms, as we discussed in Chapter 2.

95

At each well-

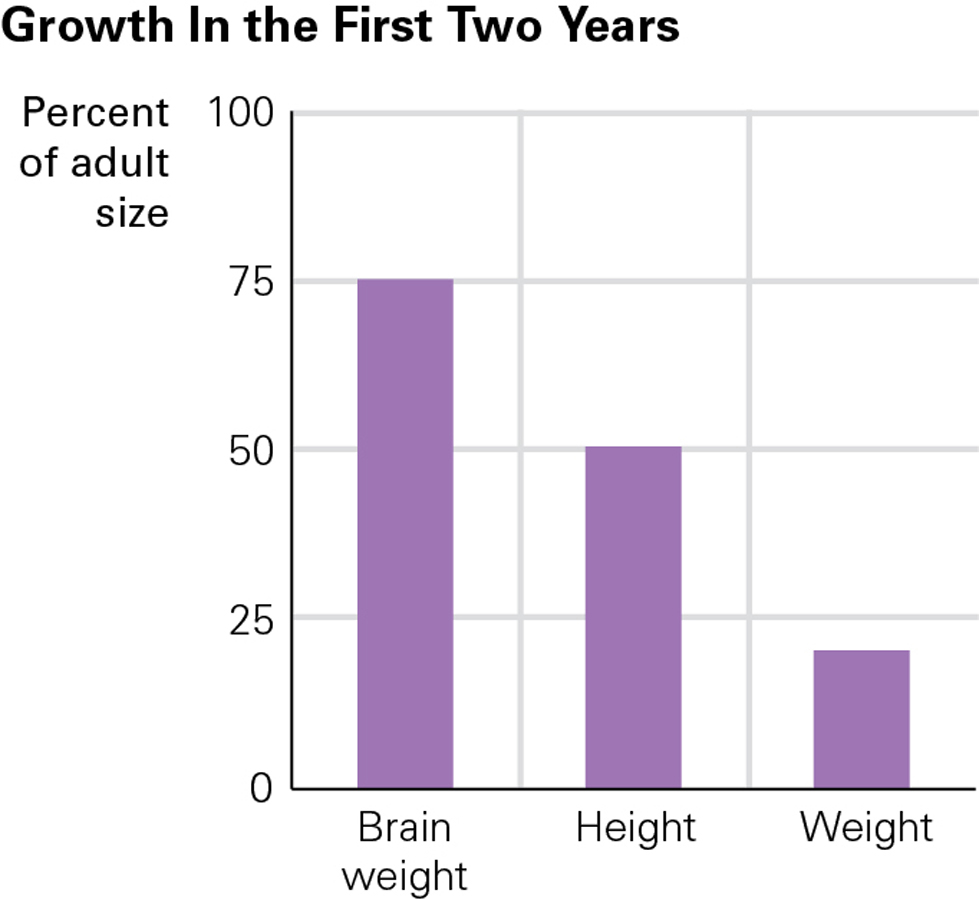

Prenatal and postnatal brain growth (measured by head circumference) is crucial for later cognition (Gilles & Nelson, 2012). If teething or a stuffed nose slow weight gain, nature protects the brain, a phenomenon called head-sparing. From two weeks after conception to 2 years, the brain grows more rapidly than any other part of the body, from about 25 percent of adult weight at birth to almost 75 percent. Over the same two years, brain circumference increases from about 36 to 48 centimetres (see Figure 3.3).

Brain Development

The brain is essential throughout life; it is discussed in every chapter of this book. We begin now with the basics—

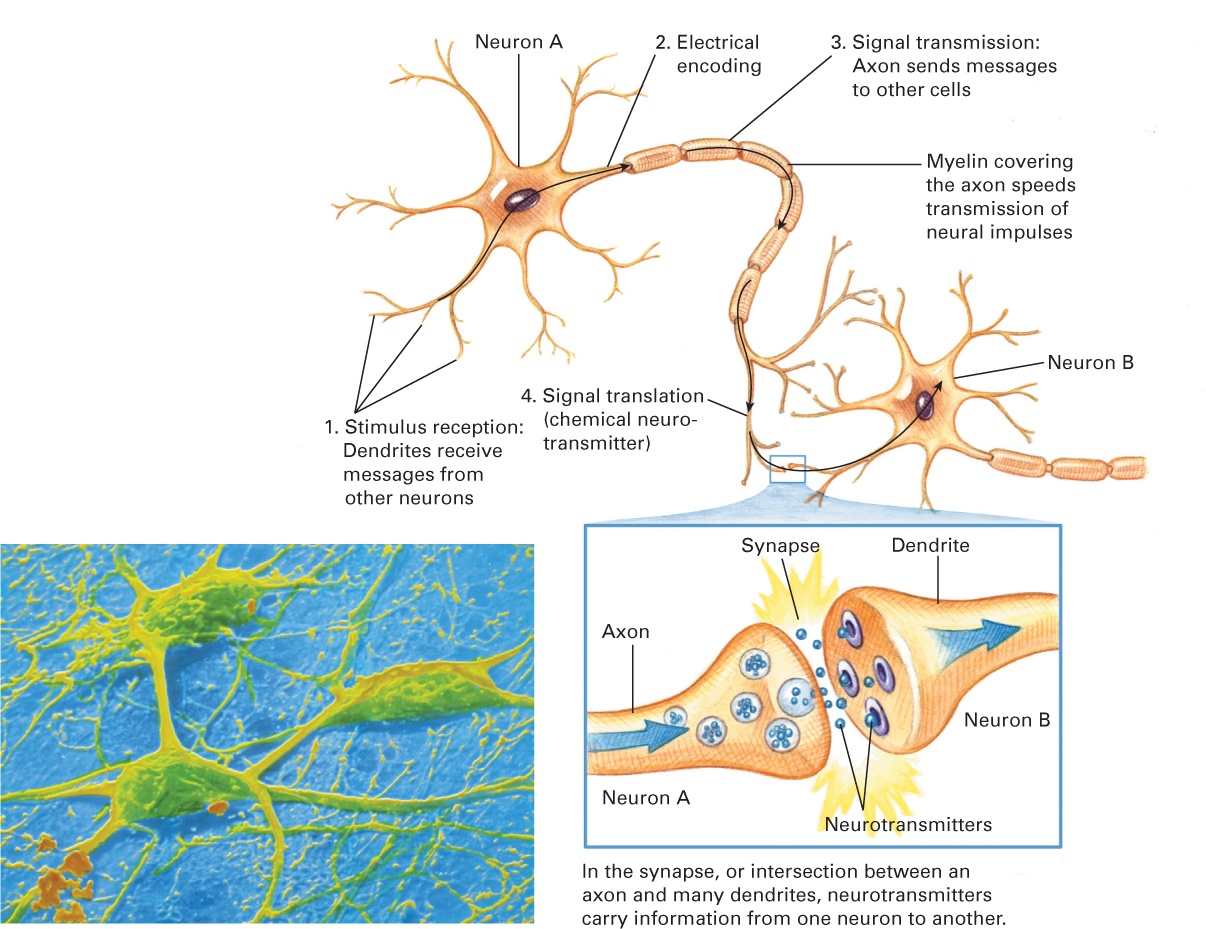

Brain BasicsCommunication within the central nervous system (CNS)—the brain and spinal cord—

Different areas of the brain have specialized functions. Some regions deep within the skull maintain breathing and heartbeat, some in the midbrain underlie emotions and impulses, and some in the cortex allow perception and cognition. For instance, there is a visual cortex, an auditory cortex, and an area dedicated to the sense of touch for each body part—

96

Within and between areas of the central nervous system, neurons are linked to other neurons by intricate networks of nerve fibres called axons and dendrites (see Figure 3.4). Each neuron has a single axon and numerous dendrites, which spread out like the branches of a tree. The axon of one neuron meets the dendrites of other neurons at intersections called synapses, tiny gaps that are critical communication links within the brain.

To be more specific, axons and dendrites do not touch at synapses. Instead, neurons communicate by sending electrochemical impulses (called neurotransmitters) through their axons to synapses, to be picked up by the dendrites of other neurons. The dendrites bring messages to the cell bodies of their neurons, which, in turn, convey the messages via their axons to the dendrites of other neurons.

Experiences and PruningAt birth, the brain contains at least 100 billion neurons, more than a person needs. However, the newborn’s brain has far fewer dendrites and synapses than the person will eventually possess. During the first months and years, rapid growth and refinement in axons, dendrites, and synapses occur, especially in the cortex. Dendrite growth is the major reason that brain weight triples from birth to age 2 years (Johnson, 2010).

An estimated fivefold increase in dendrites in the cortex occurs in the 24 months after birth, with about 100 trillion synapses being present at age 2 years. According to one expert, 40 000 new synapses are formed every second in the infant’s brain (Schore & McIntosh, 2011).

97

This extensive postnatal brain growth is highly unusual for mammals. Why does it occur in humans? Although prenatal brain development is remarkable, it is limited by the simple fact that the human pelvis is relatively small and the head must be relatively small as well to make birth possible. Thus there is an acceleration of growth after birth. In fact, unlike other species, humans must nurture and protect their offspring for more than a decade as children’s brains continue to develop (Konner, 2010).

Early dendrite growth is called transient exuberance: exuberant because it is so rapid and transient because some of it is temporary. The expansive growth of dendrites is followed by pruning. Just as a gardener might prune a rose bush by cutting away some growth to enable more, or lovelier, roses to bloom, unused brain connections atrophy and die (Stiles & Jernigan, 2010).

The specifics of brain structure and growth depend on genes and maturation but even more on experience (Stiles & Jernigan, 2010). Some dendrites wither away because they are never used—

Some children with intellectual disabilities have “a persistent failure of normal synapse pruning” (Irwin et al., 2002). That makes thinking difficult. For example, one sign of autism is more rapid brain growth, suggesting too little pruning (Hazlett et al., 2011). Yet just as too little pruning creates problems, so does too much pruning. Brain sculpting is attuned to experience: The appropriate links in the brain need to be established, protected, and strengthened while inappropriate ones are eliminated. One group of scientists speculates that “lack of normative experiences may lead to overpruning of neurons and synapses, both of which may lead to reduction of brain activity” (Moulson et al., 2009). Another group suggests that infants who are often hungry, or hurt, or neglected develop brains that compensate—

98

William Greenough and his colleagues explored the plasticity of the brain and discovered that experiences influence how the brain develops and matures. They believed that there are two types of categorization schemes present in the brain, depending on the type of information that is to be stored. The first type of scheme is the experience-

Plasticity of the BrainDuring the prenatal stage, the brain develops rapidly, as various parts take on their specialized functions. Some of this development is automatic, due to genetically predetermined pathways. However, the brain is also very vulnerable to environmental influences, and these influences can set the stage for major neurological patterns in the future (e.g., competence, health, and well-

One advantage of the brain’s plasticity is the ability to compensate or take over the functions of certain areas that may have been damaged by disease or accident. However, as just noted, such plasticity also means the brain is highly vulnerable to impoverished or restricted environments, and this can lead to damage that is significant enough to have serious implications for future development.

Some researchers have found that language and literacy assessment can provide an indication of overall brain development in the early years. The sounds of the language that infants are exposed to have been found to influence how the auditory neurons function. For example, during the first 7 to 8 months, if infants are exposed to two languages (e.g., English and French), they are more likely to speak each language idiomatically, that is, with no discernible accent. Those who learn two languages during their early years have a larger left brain (Mustard, 2006), which may assist with language acquisition and fluency.

99

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Face Recognition

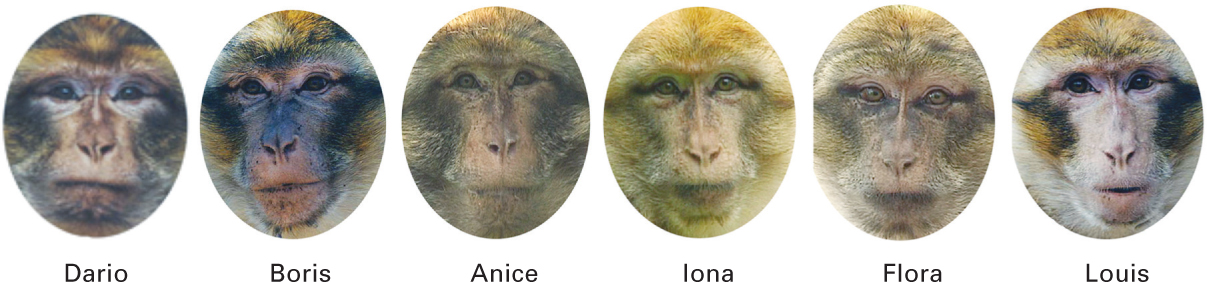

Unless you have prosopagnosia (face blindness, relatively rare), one part of your brain, the fusiform face area, is astonishingly adept at face recognition. This area is primed among newborns, although it has yet to reflect experience: Newborns stare at monkey faces as well as at human ones, and at pictures and toys with faces as well as at live faces.

Soon, experiences (such as seeing one’s parents again and again) refine perception (de Heering et al., 2010). By 3 months, most babies smile more readily at familiar people and are more accurate at differentiating faces from their own species and their own ethnic group (called the own-

The own-

The importance of early experience is further evidenced in two studies. In one, over the course of three months, 6-

For one-

The second study was premised on the fact that many children and adults do not notice the individuality of newborns. Some even claim that “all babies look alike.” However, the study found that 3-

Harm and ProtectionMost infants develop well within their culture, and head-

Because of brain plasticity and its consistent development, parents and others in the infants’ social world play an important role in the baby’s brain development. There are many simple and efficient ways of promoting healthy development. To begin with, parents need to provide a stimulating environment, which can include talking and singing to the baby, playing, massaging, and engaging in other sensory activities, all of which provide fodder for brain connections. Severe lack of stimulation (e.g., no talking at all) stunts the brain. As the saying goes, “use it or lose it.” As one review of early brain development explains, “enrichment and deprivation studies provide powerful evidence of…widespread effects of experience on the complexity and function of the developing system” (Stiles & Jernigan, 2010).

100

This does not mean that babies require spinning, buzzing, multi-

ESPECIALLY FOR Parents of Grown Children Suppose you realize that you seldom talked to your children until they talked to you, and that you often put them in cribs and playpens. Did you limit their brain growth and their sensory capacity?

Probably not. Brain development is programmed to occur for all infants, requiring only the stimulation that virtually all families provide—warmth, reassuring touch, overheard conversation, facial expressions, movement. Extras such as baby talk, music, exercise, mobiles, and massage may be beneficial, but are not essential.

A simple application of what has been learned about the prefrontal cortex is that hundreds of objects, from the very simple to the quite elaborate, can capture an infant’s attention. There is also a tragic implication: The brain is not yet under thoughtful control, since the prefrontal cortex is not well developed. Unless adults understand this, they might get angry if an infant keeps crying. Infants cry as a reflex to pain (usually digestive pain); they are too immature to decide to stop crying, as adults do.

If a frustrated caregiver reacts to crying by shaking the baby, it can cause a life-

According to one study of 364 injured children under the age of 5 years who were admitted to pediatric hospitals across Canada, 69 (19 percent) of the children died outright of their injuries. Of those who survived, 55 percent suffered long-

In 2004, the state of New York passed a law requiring mothers of newborns to watch a 15-

The fact that infant brains respond to their circumstances suggests that waiting until evidence shows that a young child has been mistreated is waiting too long. In the first months of life, babies adjust to their world, becoming withdrawn and quiet if their caregivers are depressed or becoming loud and demanding if that is the only way they get fed. Such adjustments set patterns that are destructive later on. Thus, understanding development as dynamic and interactive means helping caregivers from the start, not waiting until destructive systems are established (Tronick & Beegly, 2011). The word “systems” is crucial here. Almost every baby experiences something stressful—

101

Human brains are designed to grow and adapt; plasticity is apparent from the beginning of life (Tomalski & Johnson, 2010). It is the patterns, not the moments, of neglect or maltreatment that harm the brain.

Sleep

One consequence of brain maturation is the ability to sleep through the night. Newborns cannot do this. Normally they sleep 15–

Sleep specifics vary not only because of biology (age and genes), but also because of the social environment. With responsive parents, full-

Over the first months, the relative amount of time in various stages of sleep changes. Babies born preterm may always seem to be dozing. Full-

Overall, 25 percent of parents of children under age 3 years report that their babies have sleeping problems, according to an Internet study of more than 5000 North Americans (Sadeh et al., 2009). Sleep problems are more troubling for parents than for infants. This does not render them insignificant; overtired parents may be less patient and responsive (Bayer et al., 2007). Patience is also needed to ensure the baby’s sleep position is properly “back to sleep,” to protect against sudden infant death syndrome (see Chapter 1).

One problem for parents is that advice about where infants should sleep varies, from contending that infants should sleep beside their parents—

102

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Where Should Babies Sleep?

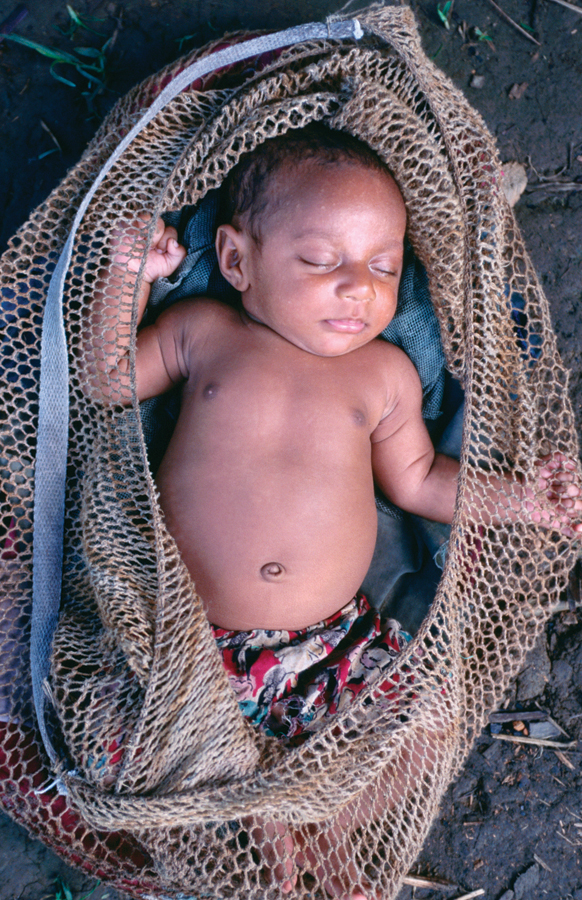

Traditionally, most middle-

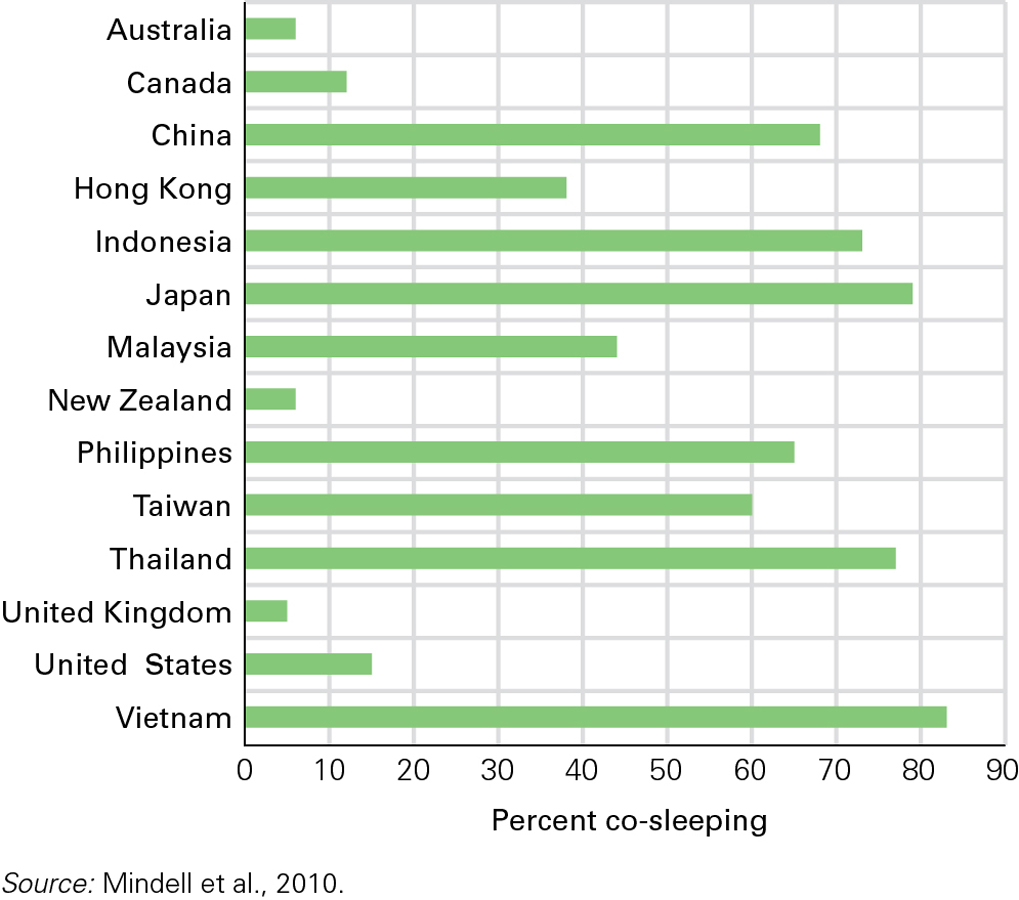

Even today, at baby’s bedtime, Asian and African mothers worry more about separation, whereas European and North American mothers worry more about lack of privacy. A study in 19 nations confirms that parents act on their fears: The extremes were 82 percent of babies in Vietnam sleeping with their parents compared to 6 percent of babies in New Zealand (Mindell et al., 2010) (see Figure 3.5).

At first, this may seem to be a matter of income: Families of low socioeconomic status (SES) are less likely to have an extra room. But even wealthy Japanese families often co-

The argument for co-

Yet the argument against co-

Furthermore, adult beds, unlike cribs, are often soft, with comforters, mattresses, and pillows that increase the risk of suffocation (Alm, 2007). A commercial solution is a “co-

One reason for opposing views is that every adult is affected by his or her long-

One study found that, compared with Israeli adults who had slept near their parents as infants, those who had slept communally with other infants (as sometimes occurred on a kibbutz) often interpreted their own infants’ nighttime cries as distress requiring comfort (Tikotzky et al., 2010). In other words, a ghost from the past is affecting current behaviour; when parents think their crying babies are frightened, lonely, and distressed, they want to respond quickly. Quick responses are more possible with co-

A developmental perspective begins with what we know: Infants learn from their earliest experiences. If babies become accustomed to bed-

Of course, that concern reflects a cultural norm as well. According to an ethnographic study, by the time Mexican Mayan children are 5 years old, they choose when, how long, and with whom to sleep (Gaskins, 1999), a practice that bewilders many other North Americans.

103

Developmentalists hesitate to declare any particular pattern best (Tamis-

ESPECIALLY FOR New Parents You are aware of cultural differences in sleeping practices, which raises a very practical issue: Should your newborn sleep in bed with you?

From psychological and cultural perspectives, babies can sleep anywhere as long as the parents can hear them if they cry. The main consideration is safety: Infants should not sleep on a mattress that is too soft. Otherwise, each family should decide for itself.

KEY Points

- Weight and height increase markedly in the first two years; the norms are three times the baby’s birth weight by age 1, and 30 centimetres taller than birth height by age 2.

- Brain development is rapid during infancy, particularly development of the axons, dendrites, and synapses within the cortex.

- Since experience shapes the infant brain, the infant’s environment plays an important role; pruning eliminates unused connections.

- Where and how much infants sleep is shaped by brain maturation and family practices.