3.5 Language

No other species has anything approaching the neurons and networks that support the 6000 or so human languages. The human ability to communicate, even at age 2 years, far surpasses that of full-

Here we describe the specific steps in human language learning, “from burp to grammar” as one scholar put it (Saxton, 2010). We then ask: How do babies do it?

125

The Development of Spoken Language in the First Two Years

| Age* | Means of Communication |

| Newborn | Reflexive communication— |

| 2 months | A range of meaningful noises— |

|

3- |

New sounds, including squeals, growls, croons, trills, vowel sounds. |

|

6- |

Babbling, including both consonant and vowel sounds repeated in syllables. |

| 10- |

Comprehension of simple words; speech- |

| 12 months | First spoken words that are recognizably part of the native language. |

| 13- |

Slow growth of vocabulary, up to about 50 words. |

| 18 months | Naming explosion— |

| 21 months | First two- |

| 24 months | Multiword sentences. Half the toddler’s utterances are two or more words long. |

| *The ages of accomplishment in this table reflect norms. Many healthy children with normal intelligence attain these steps in language development earlier or later than indicated here. | |

The Universal Sequence

The timing of language acquisition varies; the most advanced 10 percent of 2-

Listening and RespondingInfants who can hear begin learning language before birth, via brain connections. They prefer the language their mother speaks over an unheard language; newborns of bilingual mothers respond to both languages and differentiate between them (Byers-

Newborns look closely at facial expressions, apparently trying to connect words and expressions, to understand what is being communicated. By 6 months, infants can tell whether a person is speaking their native language or not, just by looking at the person’s mouth movements (no sound) (Weikum et al., 2007). The ability to distinguish sounds and gestures in the language (or languages) of caregivers improves over the first year, while the ability to hear sounds never spoken in the native language deteriorates (Narayan et al., 2010).

Adults everywhere use higher pitch, simpler words, repetition, varied speeds, and exaggerated emotional tones when they speak to infants (Bryant & Barrett, 2007). This special language form is sometimes called baby talk, since it is talk directed to babies, and sometimes called motherese or parentese, since mothers and other caregivers—

126

DANIEL GERMAN

No matter what term is used or who is speaking it, child-

Sounds are preferred over content. Infants like alliteration, rhymes, repetition, rhythm, and varied pitch (Hayes & Slater, 2008; Schön et al., 2008). Think of your favourite lullaby (itself an euphonious word). All infants listen to whatever they can and appreciate the sounds they hear. Even music is culture-

BabblingAt first, babies mostly listen. By 6 months they start practising sounds, repeating certain syllables (ma-

Toward the end of the first year, babbling begins to sound like the infant’s native language; infants imitate what they hear in accents, cadence, consonants, and so on. Gestures also become more specific, with all babies (deaf as well as hearing) expressing concepts with gestures sooner than with speech (Goldin-

127

One early gesture is pointing, typical in human babies at 10 months. Pointing is an advanced social gesture that requires understanding another person’s perspective. Most animals cannot interpret pointing; most 10-

First WordsFinally, at about 1 year, the average hearing baby utters a few words, although some hearing babies do not begin to talk until about 18 months. Caregivers usually understand the first words before strangers do, which makes it hard for researchers to pinpoint exactly what a 12-

ESPECIALLY FOR Caregivers A toddler calls two people “Mama.” Is this a sign of confusion?

Not at all. Toddlers hear several people called “Mama” (their own mother, their grandmothers, their cousins’ and friends’ mothers) and experience mothering from several people, so it is not surprising if they use “Mama” too broadly. They will eventually narrow the label down to the one correct person.

Spoken vocabulary increases gradually (perhaps one new word a week). However, 6-

Careful tracing of early language from the information-

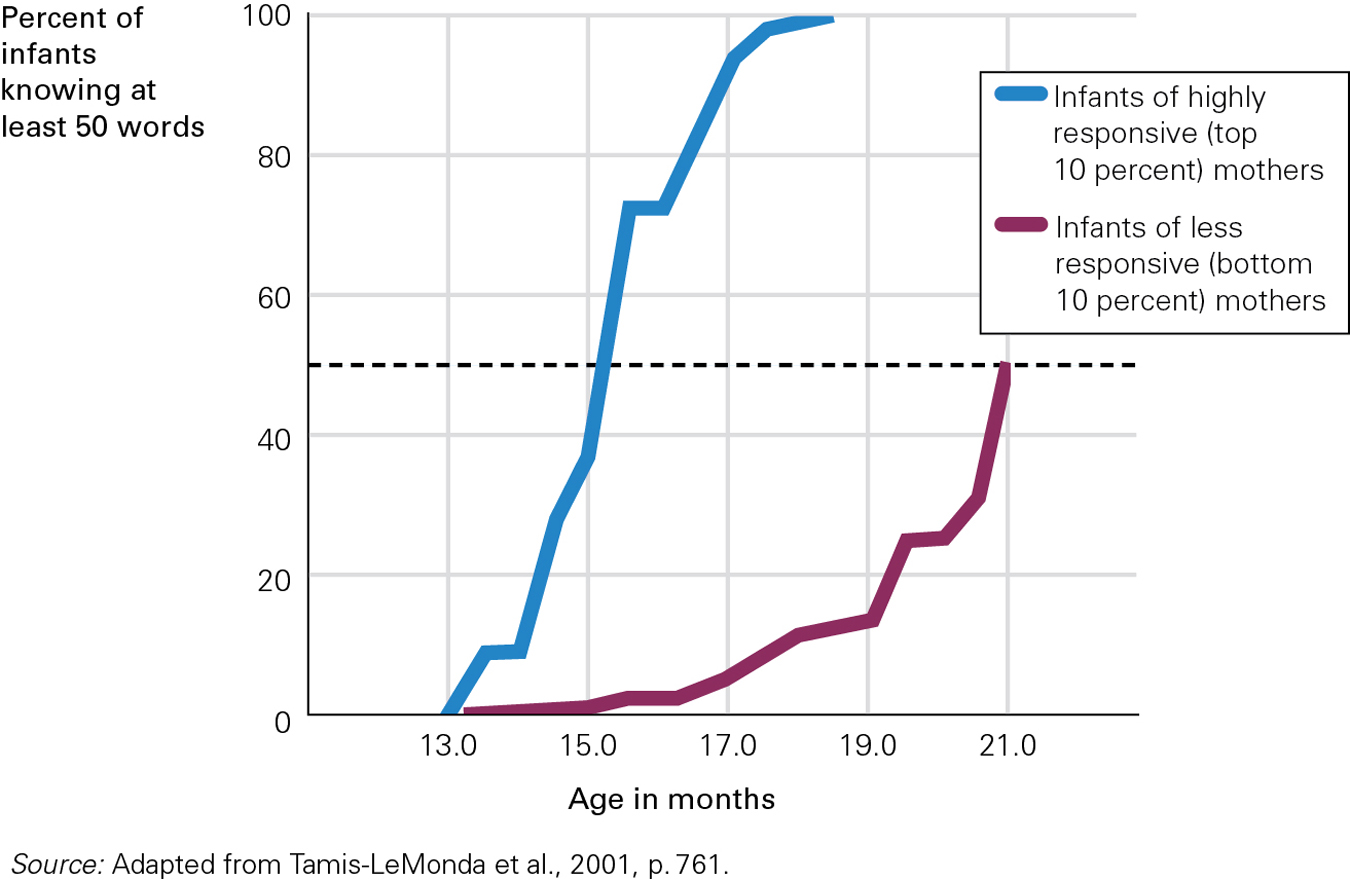

Once vocabulary reaches about 50 expressed words (understood words are far more extensive), it builds rapidly, at a rate of 50 to 100 words per month, with 21-

128

Cultural Differences

Early sequence and sounds of languages are universal, but there are many differences that soon emerge. For instance, about 30 languages of the world use a click sound as part of spoken words; infants there become adept at clicking. Similarly, the rolled “r,” the enunciated “l” or “th,” and the difference between “b” and “v” are mastered by infants in some languages but not others, depending on what they hear.

Although all new talkers say more nouns than any other parts of speech, the ratio of nouns to verbs varies from place to place. For example, by 18 months, English-

One explanation goes back to the language itself. Mandarin and Korean are “verb-

An alternative explanation considers the entire social context: Playing with a wide range of toys and learning about dozens of objects are crucial in North American culture, whereas East Asian cultures emphasize human interactions—

Accordingly, North American infants are expected to learn to name many objects, whereas Asian infants are expected to act on objects and respond to people. Thus, Chinese toddlers might learn the equivalent of come, play, love, carry, run, and so on before Canadian ones (Chan et al., 2009). This is the result of experience, not genes. A toddler of Chinese ancestry growing up in an English-

A simpler explanation is that young children are sensitive to the sounds of words, with some sounds more salient than others. Verbs are learned more easily if they sound like the action (Imai et al., 2008), and such verbs may be more common in some languages than others.

In English, most verbs are not onomatopoeic, although perhaps jump, kiss, and poop—all learned relatively early on—

Putting Words TogetherGrammar includes all the methods that languages use to communicate meaning. Word order, prefixes, suffixes, intonation, verb forms, pronouns and negations, prepositions and articles—

Grammar can be discerned in holophrases but becomes obvious between 18 and 24 months, when two-

Young children can master two languages, not just one. The crucial variable is how much speech in both languages the child hears. Listening to two languages does not necessarily slow down the acquisition of grammar, but “development in each language proceeds separately and in a language specific manner” (Conboy & Thal, 2006). In Canada, where English and French are the official languages, many infants acquire both. This is referred to as bilingual first language acquisition (BFLA). Statistics Canada estimates that in 2006, almost 18 percent of the population was fluent in both French and English (Corbeil & Blaser, 2009).

129

A review by Fred Genesee of McGill University is one of several recent studies to explore whether BFLA in any way strains a child’s language-

- Children who are bilingual have greater difficulty in learning grammar than children who speak one language. In fact, bilingual children have similar rates of language development as monolingual children, at least in their dominant language (Nicoladis & Genesee, 1996; Paradis & Genesee, 1996). (Note that for various reasons, most dual-

language learners become more proficient in one language than the other [Genesee, 2009].) - Children who are monolingual speak their first words sooner and learn words faster than children who are bilingual. Again, research shows that monolingual and bilingual children produce their first words at about the same time. They also show similar rates in the growth of their vocabulary (Pearson et al., 1993; Pearson & Fernandez, 1994).

- Dual-

language learners face more communication challenges than monolingual children. Actually, bilingual children have about the same number of communication challenges as children who speak only one language. Interestingly bilingual children often become more skilled in interpersonal communications at an earlier age since they switch between languages depending on context and the preferences of the person they are speaking to (Vihman, 1998).

ESPECIALLY FOR Educators An infant daycare centre has a new child whose parents speak a language other than the one the teachers speak. Should the teachers learn basic words in the new language, or should they expect the baby to learn their language?

Probably both. Infants love to communicate, and they seek every possible way to do so. Therefore, the teachers should try to understand the baby and the baby’s parents, but they can also teach another language.

Indeed, some evidence suggests that children are statisticians: They implicitly track the number of words and phrases and learn those expressed most often. That is certainly the case when children are learning their mother tongue; it is probably true when learning a second language as well (Johnson & Tyler, 2010).

Bilingual toddlers soon realize differences between languages, adjusting tone, cadence, and vocabulary when speaking to a monolingual person. Most bilingual children have parents who are also bilingual; hence, these children mix languages because they know their parents will understand.

Note that mixing languages is a cultural adaptation, not a sign of mental deficiency. In fact, bilingual children and adults seem to have a cognitive advantage over monolingual people, as noted in Chapter 5.

How Do They Do It?

Worldwide, people who are not yet 2 years old already speak their native tongue. They continue to learn rapidly: Some teenagers compose lyrics or deliver orations that move thousands of their co-

Theory One: Infants Need to Be TaughtThe seeds of the first perspective were planted more than 50 years ago, when the dominant theory in North American psychology was behaviourism, or learning theory. The essential idea was that all learning is acquired, step by step, through association and reinforcement. Just as Pavlov’s dogs learned to associate the sound of a tone with the presentation of food (see Chapter 1), behaviourists believe that infants associate objects with words they have heard often, especially if reinforcement occurs.

130

B. F. Skinner (1957) noticed that spontaneous babbling is usually reinforced. Typically, every time the baby says “ma-

The core ideas of this theory are:

- parents are expert teachers, although other caregivers help

- frequent repetition is instructive, especially when linked to daily life

- well-

taught infants become well- spoken children.

Behaviourists note that some 3-

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Why does the blue line end at 18 months?

By 18 months, every one of the infants of highly responsive mothers (top 10 percent) knows 50 words. Not until 30 months do all the infants with quiet mothers reach the naming explosion.

Theory Two: Culture Fosters Infant LanguageThe second theory arises from the sociocultural reason for language: communication. According to this perspective, infants communicate because humans are social beings, dependent on one another for survival and joy. Each culture has practices that further social interaction; talking is one of those practices.

It is the emotional messages of speech, not the words, that are the focus of early communication, according to this perspective. In one study, people who had never heard English (Shuar hunter–

131

For example, many 1-

According to theory two, then, social impulses, not explicit teaching, lead infants to learn language “as part of the package of being a human social animal” (Hollich et al., 2000). Those same impulses are evident in all the ways infants learn. According to this theory, people differ from the great apes in that they depend on others within their community and thus learn whatever way their culture uses to communicate. Every infant (and no chimpanzee) masters words and grammar to join the social world in which he or she finds himself (Tomasello & Herrmann, 2010).

Cultures vary not only in the languages they speak, but also in how they communicate, some using gestures and touch more than words. A learning theorist might consider the quieter, less verbal child to be developmentally delayed, but this second perspective contends that the crucial aspect of language is social communication, and that the quieter child may simply be communicating in another way. Language is not necessarily spoken.

Theory Three: Infants Teach ThemselvesA third theory holds that language learning is innate; adults need not teach it, nor is it a by-

ESPECIALLY FOR Nurses and Pediatricians Bob and Joan have been reading about language development in children. Because they are convinced that language is “hardwired,” they believe they don’t need to talk to their 6-

While much of language development is indeed hard-wired, many experts assert that exposure to language is required. You don’t need to convince Bob and Joan of this point, though—just convince them that their baby will be happier if they talk to him.

The seeds of this perspective were planted soon after Skinner proposed his theory of verbal learning. Noam Chomsky (1968, 1980) and his followers felt that language is too complex to be mastered merely through step-

Noting that all young children master basic grammar at about the same age, Chomsky cited this universal grammar as evidence that humans are born with a mental structure that prepares them to seek some elements of human language—

Other scholars agree with Chomsky that infants are innately ready to use their minds to understand and speak whatever language is offered. All babies are eager learners, and language may be considered one more aspect of neurological maturation (Wagner & Lakusta, 2009). This idea does not strip languages and cultures of their differences in sounds, grammar, and almost everything else, but the basic idea is that “language is a window on human nature, exposing deep and universal features of our thoughts and feelings” (Pinker, 2007).

The various languages of the world are all logical, coherent, and systematic. Infants are primed to grasp the particular language they are exposed to, making caregiver speech “not a ‘trigger’ but a ‘nutrient’” (Slobin, 2001). There is no need for a trigger, according to theory three, because the developing brain quickly and efficiently connects neurons and dendrites to support whichever language the infant hears.

132

Research supports this perspective as well. As you remember, newborns are primed to listen to speech (Vouloumanos & Werker, 2007), and all infants babble ma-

All True?Which of these three perspectives is correct? Perhaps all of them. In one monograph that included details and results of 12 experiments, the authors presented a hybrid (which literally means “a new creature, formed by combining other living things”) of previous theories (Hollich et al., 2000).

Since infants learn language to do numerous things—

After intensive study, another group of scientists also endorsed a hybrid theory, concluding that multiple attentional, social and linguistic cues contribute to early language (Tsao et al., 2004). It makes logical and practical sense for nature to provide several paths toward language learning and for various theorists to emphasize one or another of them (Sebastián-

Some scholars, inspired by evolutionary theory, think that language is the crucial trait that makes humans unlike any other species—

Adults need to talk often to infants (theory one), encourage social connections (theory two), and appreciate the innate abilities of the child (theory three). As one expert concludes,

in the current view, our best hope for unraveling some of the mysteries of language acquisition rests with approaches that incorporate multiple factors, that is, with approaches that incorporate not only some explicit linguistic model, but also the full range of biological, cultural, and psycholinguistic processes involved.

[Tomasello, 2006]

The idea that every theory is correct in some way may seem uncritical, naïve, and idealistic. However, a similar conclusion was arrived at by scientists extending and interpreting research on language acquisition. They contend that language learning is neither the direct product of repeated input (behaviourism) nor the result of a specific human neurological capacity (LAD). Instead, different aspects of language may have evolved in different ways, and as a result a piecemeal and empirical approach is needed (Marcus & Rabagliati, 2009). In other words, a single theory that explains how babies learn language does not reflect the data: Humans accomplish this feat in many ways.

Infants are active learners not only of language (as just outlined) and of perceptions and motor skills (as explained in the first half of this chapter), but also of everything else in their experience. Active and interactive social and emotional understandings are described in the next chapter.

133

KEY Points

- Infants pay close attention to the sounds and rhythms of speech, comprehending far more than they can say.

- Infants learn rapidly to communicate and to speak, starting with cries in the first weeks and progressing to words by 1 year and sentences before age 2.

- Culture affects the timing and types of words acquired.

- Some experts emphasize the importance of adult reinforcement of early speech; others suggest that language learning is innate; others believe it is a by-

product of social impulses. - A hybrid explanation suggests that language learning occurs in many ways, depending on the specific age, culture, and goals of the infant.