4.2 Brain and Emotions

As the brain develops rapidly, not only do infants’ cognitive abilities increase (as you read in Chapter 3), but their emotional abilities increase as well (Johnson, 2010). When the infant’s brain responds to various experiences in his or her environment, important connections (neural pathways) are formed.

142

Links between expressed emotions and brain growth are complex and are difficult to assess and describe (Lewis, 2011). Compared to the emotions of adults, discrete emotions during early infancy are murky and unpredictable. For instance, an infant’s cry can be triggered by pain, fear, tiredness, surprise, or excitement; laughter can quickly turn to tears. Furthermore, infant emotions may erupt, increase, or disappear for unknown reasons (Camras & Shutter, 2010).

Growth of the Brain

Many specific aspects of brain development support social emotions (Lloyd-

Infants’ early emotional experiences guide the way that they will deal with those feelings in the future. For example, when infants experience stress, if trusted adults help them deal with the stressful event, infants develop constructive ways of dealing with future negative events. However, if infants repeatedly experience high levels of stress with little or a lack of positive adult support, the pathways that allow them to experience fear, anger, and frustration strengthen. This has future implications, as these children may be less likely to explore their environment or try new experiences, which are important for continued development and growth (Onunaku, 2005).

Thus, parents can greatly affect the “wiring” of the infant’s brain through the types of interactions they have with their infants. The unique ways that families interact is cultural; culture helps determine the infants’ developmental characteristics. For example, when and how babies are fed and parents’ response to infant cries and temper tantrums are influenced by the family’s culture.

Cultural differences may become encoded in the infant brain, called “a cultural sponge” by one group of scientists (Ambady & Bharucha, 2009). It is difficult to measure how infant brains are influenced by their context, but one study of adults (Zhu et al., 2007), half born in the United States and half in China, found that in both groups, a particular area of the brain (the medial prefrontal cortex) was activated when the adults judged whether certain adjectives applied to them. However, only in the Chinese was that area also activated when they were asked whether those adjectives applied to their mothers.

Researchers consider this to be “neuro-

Parents’ Role in Early Brain Development and Emotional DevelopmentAlthough parents’ interactions are encompassed within culture, researchers disseminate some universal advice to parents and service providers to help them support their children’s brain development in the early years. A research and advocacy organization, From Zero to Three, provides the following suggestions for healthy optimal brain development:

143

- Respond to the infant’s initiated acts (e.g., smiles, cries, babbles).

- Praise the infant when a new skill/ability is mastered.

- Talk, sing, read, and play with the infant.

- Provide interesting things for the infant to touch, smell, and chew on.

- Encourage the infant to vocalize and babble.

[Zero to Three, n.d.]

MemoryAll emotional reactions, particularly those connected to self-

Memory for events and places is evident, but memory for people is even more powerful. Particular people (typically those the infant sees most often) arouse strong emotions. Even in the early weeks, faces are connected to sensations. For example, a breastfeeding mother’s face is connected to sucking and relief of hunger. The tentative social smile at every face, which occurs naturally as the brain reaches six weeks of maturity, soon becomes a much quicker and fuller smile when an infant sees his or her parent. This occurs because the neurons that fire together become more closely and quickly connected to each other (via dendrites and neurotransmitters) with repeated experience.

Social preferences form in the early months and are connected with an individual’s face, voice, touch, and smell. This is one reason adopted children are placed with their new parents in the first days of life whenever possible, unlike 100 years ago, when adoptions were delayed until after age 1. It also is a reason to respect an infant’s reaction to a babysitter: If a 6-

StressEmotions are connected to brain activity and hormones, but the connections are complicated—

Brain scans of children who were discovered to have been maltreated in infancy show abnormal responses to stress, anger, and other emotions, and even to photographs of frightened people (Gordis et al., 2008; Masten et al., 2008). This research has led many developmentalists to suspect that abnormal neurological responses are caused by early abuse.

Quebec researchers Michael Meaney and Gustavo Turecki at the Douglas Mental Health University Institute have explored how environment can modify genes, from genetics to epigenetics. Specifically, they studied a gene called NR3C1, which produces a protein that helps individuals decrease the concentration of stress hormones in the body. The researchers examined 36 brains post-

144

The likelihood that early caregiving affects the brain throughout life leads to obvious applications (Belsky & de Haan, 2011). Since infants learn emotional responses, caregivers need to be consistent and reassuring. This is not always easy—

An infant’s crying has two possible consequences: it may elicit tenderness and desire to soothe, or helplessness and rage. It can be a signal that encourages attachment or one that jeopardizes the early relationship by triggering depression and, in some cases, even neglect or abuse.

[Kim, 2011]

Sometimes parents are blamed, or blame themselves, when their infant keeps crying. This is not helpful: Parents who feel guilty or incompetent may become angry at their baby, which may lead to unresponsive parenting, an unhappy child, and a hostile parent. But a negative relationship between difficult infants and their parents is not inevitable. Most colicky babies have loving parents and, when the colic subsides, a warm, reciprocal relationship develops. Developmentalists refer to this kind of mutual relationship as goodness of fit—

Temperament

This chapter began by describing universals of infant emotions, and then explained that brain maturation undergirds those universals. You just read that parents should not blame themselves when a baby cries often and rarely sleeps. Who, then, is to blame? When my friend had a difficult infant, she laughingly said that she and her husband wanted to exchange her for another model. And my daughter with my crying grandson (in the opening of this chapter) was upset when I said my babies were all easy. She felt I was bragging or forgetful, not sympathetic.

ESPECIALLY FOR Pediatricians and Nurses Parents come to you with their fussy 3-

It’s too soon to tell. Temperament is not truly “fixed” but variable, especially in the first few months. Many “difficult” infants become happy, successful adolescents and adults.

Genes and EmotionsCertainly not all babies are easygoing. Infant emotions are affected by alleles and prenatal events, and the uniqueness of each person means that some babies are difficult from the moment they are born. Developmentalists recognize the impact of genes and prenatal experiences. Some devote their lives to discovering alleles that affect specific emotions (Johnson & Fearon, 2011). For example, researchers have found that the 7-

Temperament is defined as the “biologically based core of individual differences in style of approach and response to the environment that is stable across time and situations” (van den Akker et al., 2010). “Biologically based” means that these traits originate with nature, not nurture. Confirmation that temperament arises from the inborn brain comes from an analysis of the tone, duration, and intensity of infant cries after the first inoculation, before much experience outside the womb. Cry variations at this every early stage were correlated with later temperament (Jong et al., 2010).

Temperament is not the same as personality, although temperamental inclinations may lead to personality differences. Generally, although personality traits (e.g., honesty and humility) are fairly stable over the course of one’s life, they are learned or acquired, and influenced by the individual’s environment, whereas temperamental traits (e.g., shyness and aggression) are genetic.

145

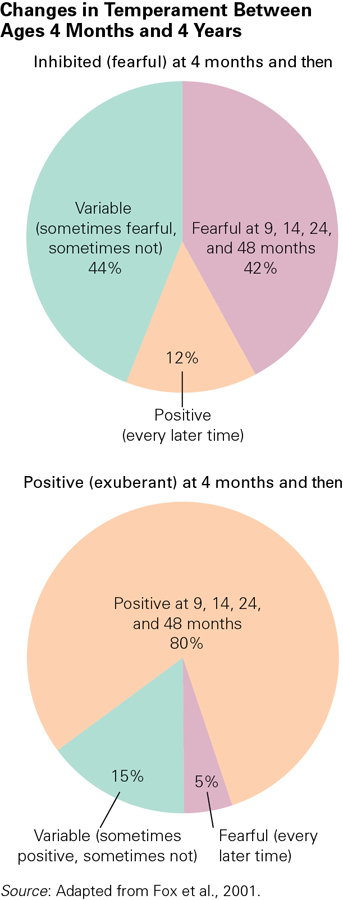

Of course, heredity and experience always interact, as shown in Figure 4.1. Although temperament originates with genes, the expression of emotions over the life span is modified by experience—

Research on TemperamentIn laboratory studies of temperament, infants are exposed to events that are frightening or attractive. Four-

These three categories (easy, difficult, slow to warm up) come from the New York Longitudinal Study (NYLS), which started in 1956 and continued for several decades, investigating infants’ individual types of personality and temperament. The NYLS was the first large study to recognize that each newborn has distinct inborn traits (Thomas & Chess, 1977). Nine characteristics were identified, and infants were scored on a three-

- motor activity

- rhythmicity or regularity of functions, such as eating, sleeping, wakefulness

- response to new people or objects (accepts or withdraws from situation)

- adaptability to changing environment

- sensitivity to stimuli

- energy level of responses

- general mood or disposition (e.g., cheerful, crying, friendly, cranky)

- distractibility

- attention span and persistence in an activity.

Researchers believed that infants can be behaviourally profiled from the scores of these nine characteristics. According to the NYLS, by 3 months, infants manifest these nine traits that cluster into four categories (the three described above and “hard to classify”). The proportion of infants in each category was as follows:

- easy – 40 percent

- difficult – 10 percent

- slow to warm up – 15 percent

- hard to classify – 35 percent.

Easy children are generally positive in mood, have regular bodily functioning, are adaptable and have a positive approach to new situations, and have a low or medium intensity of response. For parents, these infants pose few problems in caring for and training them.

Difficult children, on the other hand, have irregular bodily functions, usually display intense reactions, tend to withdraw from new situations, are slow to adapt to changes in their environment, generally have negative moods, and are seen as crying a lot. Difficult children tend to be more trying for parents, requiring them to be more consistent in their interactions and training, and more tolerant of their children’s behaviours.

146

Slow-

Later research confirms again and again that newborns differ temperamentally and that some are unusually difficult. However, although the NYLS began a rich research endeavour, the nine dimensions of the NYLS have not held up in later large studies (Caspi & Shiner, 2006; Zentner & Bates, 2008). Generally, only three (not nine) dimensions of temperament are clearly present in early childhood (Else-

- effortful control—

able to regulate attention and emotion, to self- soothe - negative mood—

fearful, angry, unhappy - surgency—

active, social, not shy, exuberant.

Research has also linked temperament to social skills and adjustment. For example, children who are negative, impulsive, and unregulated tended to have poorer peer relationships, and behaviourally inhibited children were more likely to be more anxious and depressed. However, these children with less than ideal temperaments are not doomed. Parents can influence children’s temperament so that they can develop optimally by adjusting their demands and expectations with their children’s temperament (goodness of fit).

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Linking Temperament and Parenting—

As noted, thousands of scientists have studied infant temperament. In one study, a team of Canadian researchers from Quebec sought, among other things, to find whether there is a link between a specific environmental factor—

Participants were from the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (Jetté & Des Groseilliers, 2000) and included 1516 families. In their study, the researchers focused on both reactive and proactive types of aggression. Children who display reactive aggression are usually responding to pre-

Harsh parenting is often associated with parents who show little warmth toward their children but punish them freely. In this study, the researchers measured harsh parenting by rating parents’ responses to a series of statements, such as: “When my baby cries, he/she gets on my nerves” and “I have shaken my baby when he/she was particularly fussy.”

Both mothers and fathers were first surveyed when their children were 17 months old. Then, when each child was 6 years old, the mother and the child’s teacher reported on the child’s tendencies toward reactive and proactive aggression. The report included answers to such questions as: “In the past 12 months, how often would you say that [this] child reacted in an aggressive manner when teased or threatened?” (reactive aggression), or “… used physical force to dominate other children?” (proactive aggression).

With both types of aggression, the data were clear—

The research also showed that children’s negative emotionality at age 17 months predicted the level of reactive aggression at 6 years of age. Given such a link, the importance and advantages of early intervention and education strategies, such as those for the prevention of shaken baby syndrome (see Chapter 3), are obvious.

147

KEY Points

- Brain maturation underlies much of a child’s emotional development in the first two years.

- The stress of early maltreatment probably affects the brain, causing later abnormal responses.

- Temperament is partly the result of genetic factors, with some babies much easier to take care of than others.

- Difficult or fearful babies can become successful, confident children.