5.1 Body Changes

In early childhood, as in infancy, the body and brain develop according to influential epigenetic forces. Biology interacts with culture as children eat, grow, and play.

Growth Patterns

Comparing a toddling, unsteady 1-

The centre of gravity moves from the chest to the belly, enabling cartwheels, somersaults, and many other motor skills. The joys of dancing, gymnastics, and pumping a swing become possible. Toddlers often tumble, unbalanced—

Increases in weight and height accompany this growth. Over each year of early childhood, well-

- weighs between 18 and 22 kilograms

- is at least 100 centimetres tall

- has adult-

like body proportions (legs constitute about half the total height).

Improved Motor Skills

As the body gains strength, children develop motor skills, both gross motor skills (evident in activities such as skipping) and fine motor skills (evident in activities such as drawing). Mastery depends on maturation and practice; some 6-

All, however, are physically active, practising whatever skills their culture and their friends value. If adults provide safe spaces, time, and playmates, skills develop. Children learn best from peers who do whatever the child is ready to try—

Nutritional Challenges

Nutrition at this age is very important for brain development. Because of this period of synaptic activity (which is discussed in greater detail later on), young children need high levels of fat in their diets. Up until 2 years of age, about 50 percent of their total calories should be dedicated to fat (e.g., whole milk). After about 2 years of age, the dietary fat should be reduced to no more than 30 percent of total calories, such as 1 or 2 percent cow’s milk (Zero to Three, 2013).

Over the centuries, families encouraged eating, protecting children against famine. Today, 2-

177

OverweightThe cultural practice of encouraging children to eat has turned from protective to destructive. One example is Brazil, where 30 years ago the most common nutritional problem was under-

Obesity in Canada, a joint report by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and the Canadian Institute for Health Information (2011), noted that childhood obesity has been proven to increase the risk of obesity among adults, which in turn can lead to the early development of serious medical conditions such as Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure. The report also estimated that the total economic costs of obesity in Canada range from $4.6 billion to $7.1 billion annually.

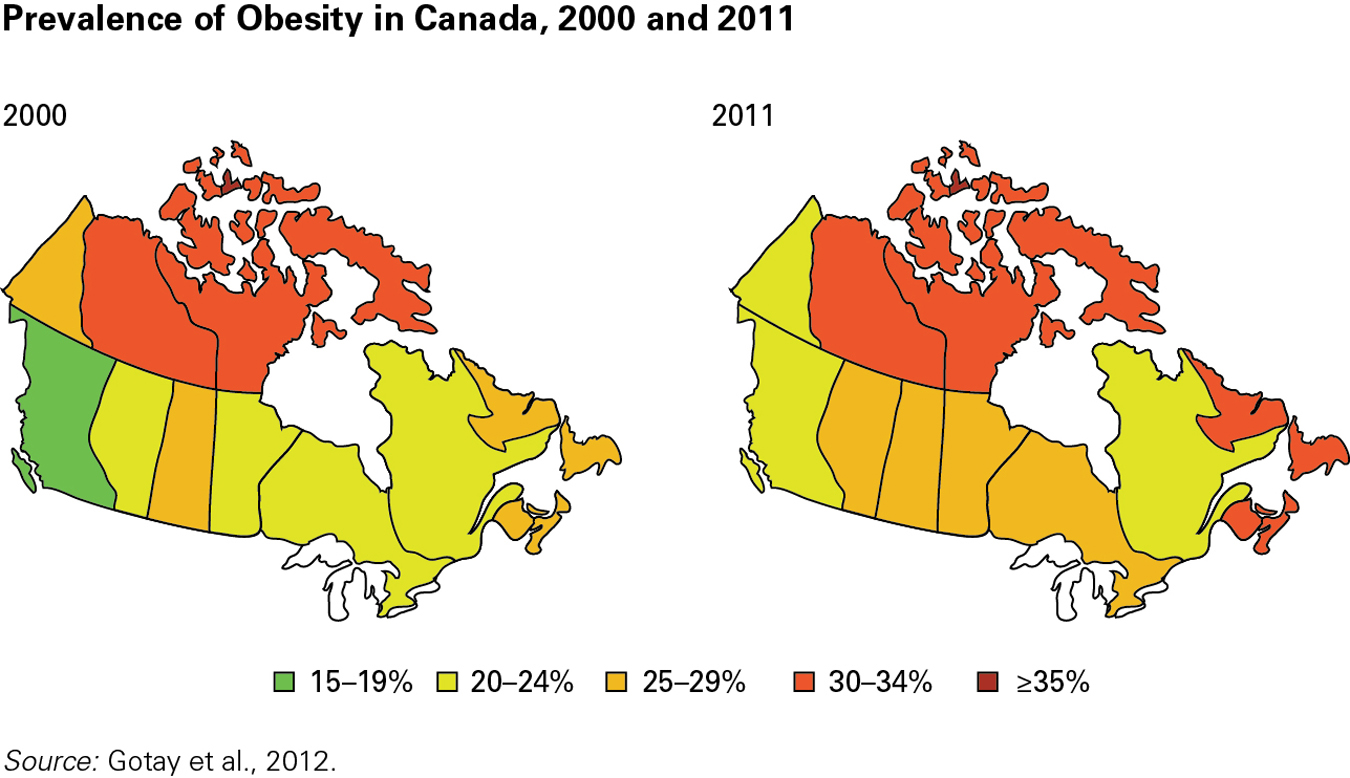

Although obesity rates in Canada are lower than in the United States (between 2007 and 2009, 34 percent of Americans were obese compared with 24 percent of Canadians), a recent report from Statistics Canada and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that Canada seems to be catching up, especially when it comes to rates of childhood obesity (Shields et al., 2011). Figure 5.1 shows that obesity rates in Canada increased significantly between 2000 and 2011. Also, according to the Government of Canada (2013a), over the last 25 years, Canada’s obesity rate has almost tripled among children and youth.

What is most disconcerting is that childhood obesity seems to have dangerous effects on a person’s physical, emotional, and social well-

ESPECIALLY FOR Nutritionists A parent complains that she prepares a variety of vegetables and fruits, but her 4-

The nutritionally wise advice would be to offer only fruits, vegetables, and other nourishing, low-fat foods, counting on the child’s eventual hunger to drive him or her to eat them. However, centuries of cultural custom make it almost impossible for parents to be wise in such cases. A physical checkup, with a blood test, may be warranted, to make sure the child is healthy.

178

Appetite decreases between 1 and 6 years of age; young children need fewer calories per kilogram. In addition, many children today get much less exercise than their grandparents did. They rarely help on the farm, walk to school, or play in playgrounds. Yet many adults still threaten and bribe their children to overeat (“Eat your dinner and you can have ice cream”). Most parents falsely think that relatively thin children are less healthy than relatively heavy ones (Laraway et al., 2010).

Nutritional DeficienciesAlthough most children consume more than enough calories, they do not always obtain adequate iron, zinc, and calcium. For example, children now drink less milk, which means weaker bones later on. Another problem is sugar. Many customs entice children to eat sweets—

Products advertised as containing 100 percent of daily vitamin requirements are sometimes misconstrued as a balanced, varied diet. In fact, healthy food is the best source of nutrition. Children who eat more vegetables and fewer fried foods usually gain bone mass but not fat, according to a study that controlled for gender and income (Wosje et al., 2010).

In developing nations, the lack of micronutrients is often severe due to a lack of variety of healthy foods. Studies have explored the effect of providing supplements, with mixed results. Providing micronutrients as part of fortified foods seems to have the best results (Ramakrishnan et al., 2011).

ESPECIALLY FOR Teachers You know that young children are upset if forced to eat a food they hate, but you have eight 3-

Remember to keep food simple and familiar. Offer every child the same food, allowing refusal but no substitutes—unless for all eight. Children do not expect school and home routines to be identical; they eventually taste whatever other children enjoy.

AllergiesUnfortunately, many parents face challenges in ensuring that their children are fed well nutritionally. Allergies are one such challenge. Between 3 to 8 percent of all young children have a food allergy, usually to a healthy, common food.

ESPECIALLY FOR Immigrant Parents You and your family eat with chopsticks at home, but you want your children to feel comfortable in Western culture. Should you change your family’s eating customs?

Children develop the motor skills that they see and practise. They will soon learn to use forks, spoons, and knives. Do not abandon chopsticks: Children can learn several ways of doing things, and the ability to eat with chopsticks is a social asset.

Diagnostic standards for food allergies vary (which explains the range of estimates). Treatment varies even more (Chafen et al., 2010). Some experts advocate avoiding the offending food. Many parents withhold their child’s first taste of peanut butter until after age 3 years. Others suggest building up tolerance, such as by giving babies a tiny bit of peanut butter (Reche et al., 2011). Many public schools and daycares are nut-

ZHANG BO/GETTY IMAGES

Since allergies are so common among young children, in 2012 the Government of Canada began to enforce stronger labelling regulations for food products containing allergens. The new regulations require food manufacturers to include clearer and more comprehensive labels on their packaging so that consumers can avoid products with ingredients that might make them ill. In drawing up the regulations, the government identified a list of 10 “priority allergens” that are most likely to cause serious reactions among Canadian consumers: peanuts, tree nuts, milk, eggs, seafood, soy, wheat, sesame seeds, mustard, and sulphites. The government also clarified its labelling requirements for gluten-

179

ObsessionsFeeding young children a varied diet is also complicated by the strong preferences that many of them have for routines. In some families, children are accustomed to having an after-

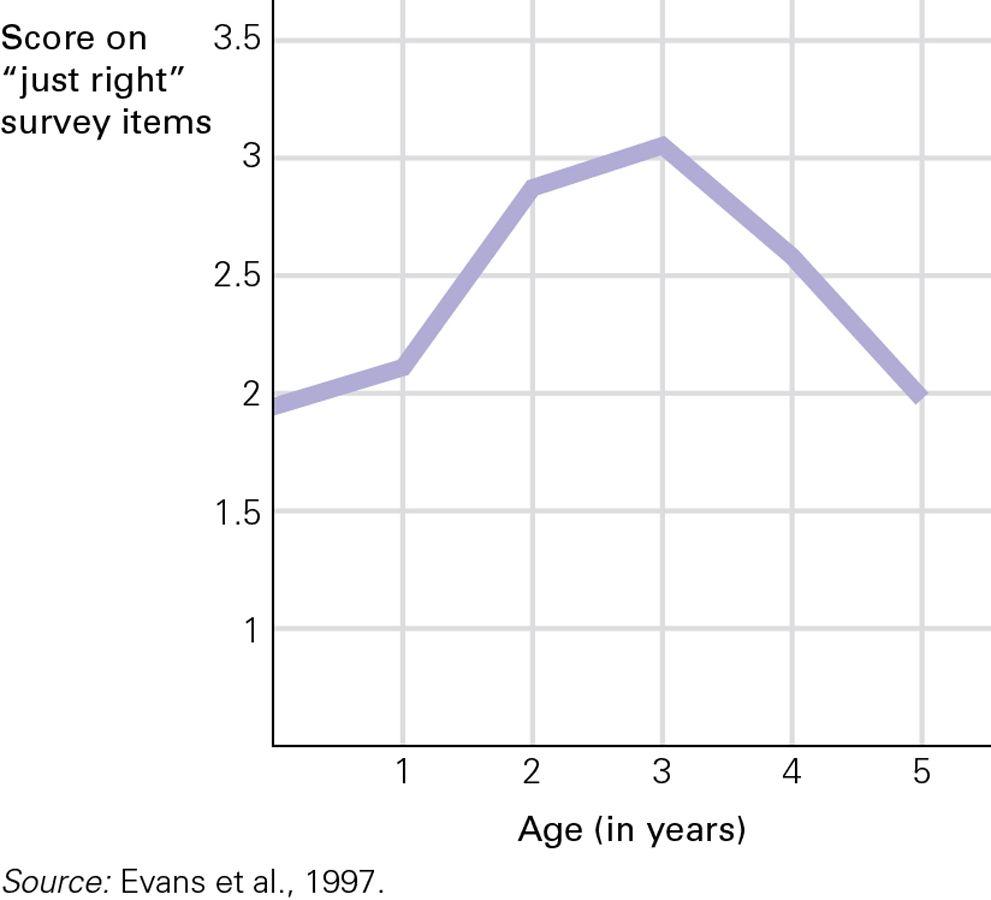

Similarly, some children insist on certain foods, prepared and served in a particular way. This rigidity, known as just right, is held strongly by many children because they have a desire for continuity and sameness. This occurs around age 3 (Evans & Leckman, 2006; Pietrefesa & Evans, 2007). Even familiar foods may be rejected if presented in a new way.

After age 5, rigidity fades (see Figure 5.2). The best reaction may be patience: A young child’s insistence on a particular routine, a favourite cup, or a preferred cereal can be accommodated for a year or two. For children, routines need to be simple, clear, and healthy; then they can be accommodated until the child is ready to change.

Oral HealthToo much sugar and too little fibre cause another common problem, tooth decay, which affects one-

Avoidable Injuries

Worldwide, injuries cause millions of premature deaths among adults as well as children. Not until age 40 does any specific disease overtake accidents as a cause of mortality (World Health Organization, 2010). Two-

In Canada, unintentional injuries kill more children and youth (ages 1–

180

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Eliminating Lead

Lead was targeted as a poison a century ago (Hamilton, 1914). The symptoms of plumbism, as lead poisoning is called, were obvious—

The lead industry defended the heavy metal as an additive, arguing that low levels were harmless and that parents needed to prevent their children from eating chips of lead paint (which taste sweet). Developmental scientists noted that the correlation between lead exposure and the symptoms mentioned above does not prove causation. Children with high levels of lead in their blood were often from low-

Consequently, lead remained a major ingredient in paint (it speeds drying) and in gasoline (it raises octane) for most of the twentieth century. The fact that babies in lead-

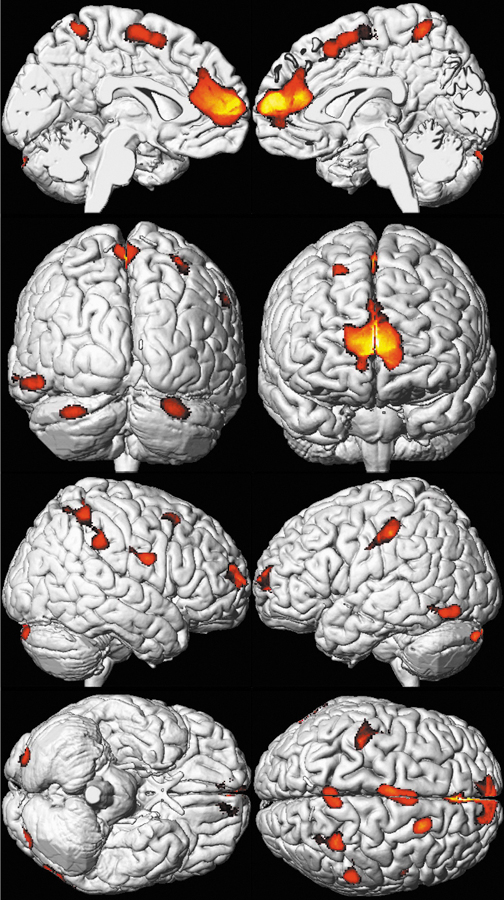

Finally, chemical analysis of blood and teeth, better intelligence tests, and careful longitudinal and replicated research proved that lead was indeed a poison, even at relatively low levels (Needleman et al., 1990, Needleman & Gatsonis, 1990). In Canada, the federal government began reducing lead levels in paint in 1976, and today lead is no longer used in household paints. The Canadian government outlawed leaded gas for automobiles in 1990. Yet, some lead sources are still unregulated, resulting in high levels in drinking water and jet fuel. Some people feel that may be harmless. However, pediatricians have set the acceptable level, formerly 40 micrograms per decilitre of blood, at 10 micrograms or less. One team contends that even 5 micrograms per decilitre is too much (Cole & Winsler, 2010), especially in a young child whose brain is rapidly developing.

The result of policies and regulations to protect against the dangers of lead is that contemporary children in North America have much lower levels of lead in their blood. According to the Canadian Health Measures Survey, lead levels in the blood of Canadians aged 6–

In addition to governments implementing laws and policies to reduce exposure to lead, parents can take action as well. Specifics include increasing children’s consumption of calcium, wiping window ledges clean of dust, testing drinking water, replacing old windows, and making sure children do not swallow peeling chips of lead-

As well, every young child should be tested—

Remember from Chapter 1 that scientists use data collected for other reasons to draw new conclusions. This is the case with lead. About 15 years after the sharp decline in the number of preschool children with high blood lead levels, the rate of violent crime committed by teenagers and young adults fell sharply. Year-

A scientist comparing these two trends concluded that some teenagers commit impulsive, violent crimes because their brains were poisoned by lead when they were preschoolers. The correlation is found in every nation that has reliable data on lead and crime—

181

The Canadian Paediatric Society (CPS) has pointed out that death rates from unintentional injuries among children and teens are three to four times higher in Aboriginal communities than elsewhere in Canada. Among Aboriginal children younger than 10 years of age, the leading causes of death due to injuries are fires and motorized vehicle accidents, including those involving snowmobiles and ATVs (Banerji, 2012). These disproportionately high rates have led the CPS to make six specific recommendations to reduce the number of deaths among Aboriginal children:

- Focus on surveillance: Involve better data collection and research.

- Improve education: Share information through conferences, public debates, and meetings with community members.

- Strengthen advocacy: Cooperate among federal, provincial, and territorial governments in developing a national injury-

prevention strategy. - Reduce barriers: Make particular efforts to reduce rates of poverty and substandard housing and increase access to drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs.

- Evaluate initiatives: Measure the impact of injury-

prevention programs. - Provide resources: Have effective funding for injury-

prevention programs and research.

Note that throughout this discussion, we have been referring to these injuries as “unintentional,” not “accidental.” Even though such injuries are not deliberate, public health experts do not call them “accidents.” The word implies that such an injury is random and unpredictable. Instead of accident prevention, health workers seek injury control (or harm reduction). Serious injury is unlikely if a child falls on a safety surface instead of on concrete, if a car seat protects the body in a crash, if a bicycle helmet cracks instead of a skull, or if pills are in a bottle with a child-

Environmental HazardsLess obvious than unintentional injuries are dangers from pollutants that harm young, growing brains and bodies more than older, developed ones. For example, in India, one city of 14 million (Kolkata, formerly Calcutta) has such extensive air pollution that childhood asthma rates are soaring and lung damage is prevalent. In these circumstances, supervision is not enough: Regulation makes a difference. In the Indian city of Mumbai (formerly Bombay), air pollution has been reduced and children’s health has been improved through several measures, including an extensive system of public buses that use clean fuels (Bhattacharjee, 2008).

A study in western Canada (Clark et al., 2010) examined the health impacts of air pollution. Some suspected pollutants, such as car and truck exhaust, were proven to be harmful to children, but others, such as woodsmoke, were not. Much more research on pollutants in food and water is needed.

Harm ReductionThree levels of harm reduction apply to every childhood health and safety issue:

- Primary prevention structures the environment to make harm less likely, reducing everyone’s risk of sickness, injury, or death. Universal immunization and less pollution are examples of primary prevention.

- Secondary prevention is more specific, averting harm in high-

risk situations or for vulnerable individuals. For instance, for children who are genetically predisposed to obesity, secondary prevention might mean exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months, no soft drinks or sweets in the kitchen for anyone, and frequent play outside.

- Tertiary prevention begins after harm has occurred, limiting the potential damage. For example, if a child falls and breaks an arm, a speedy ambulance and a sturdy cast are tertiary prevention.

182

How would these three levels apply to preventing child deaths from drowning? Tertiary prevention might be immediate mouth-

Tertiary prevention is most visible, but primary prevention is most effective (Cohen et al., 2010). Harm reduction begins long before any particular child or parent does something foolish. For developmentalists, a systems approach helps pinpoint effective prevention.

When a child is seriously injured, analysis can find causes in the microsystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. For example, if a child pedestrian is hit by a car, the analysis would note the nature of the child (young boys are hit more often than older girls) and the possible lack of parental supervision (microsystem); the local speed limit, sidewalks, and traffic lights (exosystem); and the regulations regarding drivers, cars, and roadways (macrosystem).

Researchers seek empirical data in any scientific approach. For example, the rate of childhood poisoning has decreased since pill manufacturers adopted bottles with safety caps—

Some adults say that children today are overprotected, with fewer swings and jungle gyms, mandated car seats, and nut-

DAVID R. FRAZIER/DANITADELIMONT.COM

183

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Safety Versus Freedom

How far should schools go to accommodate children with allergies? My friend has a child with a peanut allergy, and she expects the school to go peanut free for him. On the one hand, it seems selfish to go to that extent for one child (or a few children). Wouldn’t a peanut-

—Edited entry from an online parenting forum

Sara Shannon’s daughter Sabrina was a 13-

Sabrina had the fries for lunch and almost immediately experienced an allergic reaction. Short of breath and disoriented, she walked to the school office, where she collapsed before staff could administer the anti-

The coroner determined that Sabrina’s allergic reaction was probably the result of cross-

Sabrina’s untimely and tragic death made her parents resolve to do whatever they could to ensure that no other child would suffer a similar fate. Soon they were joined by families of other children with allergies, and together they formed organizations that lobbied provincial politicians.

As a direct result, in 2005 the Ontario government passed a law called An Act to Protect Anaphylactic Pupils: Sabrina’s Law. This was the first piece of legislation in the world designed to shield children with serious allergies from contamination threats at school. It has served as a model for laws and policy directives in several Canadian provinces. For example, Manitoba passed a similar law in 2008, and Alberta issued an Allergy and Anaphylaxsis Policy Advisory in 2007.

In the United States, several states now have laws or policy guidelines that clearly outline steps and procedures to make schools safer for children with severe allergies. In 2011, the U.S. federal government passed the Food Allergy and Anaphylaxsis Management Act (FAAMA), which identifies a set of “voluntary allergy management guidelines” for schools.(Smith, 2011).

Although these initiatives have saved children’s lives, they have also created controversy. Some parents feel that the rights of the majority are being compromised for the sake of a minority. Although the number of children with food allergies has definitely risen over the last several years, they still make up less than 5 percent of the total under-

Most of the controversy centres on so-

What do developmentalists think of this? Dr. Nicholas Christatis, a Harvard professor and social scientist, was quoted in Time magazine in 2009 criticizing some of the more extreme precautions schools have taken as a form of “societal hysteria.” “There are some kids with severe allergies,” said Dr. Christatis, “and they need to be taken seriously, but the problem with a disproportionate response is that it feeds the hysteria” (Sharples, 2009).

184

Dr. Robert Wood of the Johns Hopkins Children’s Center also cautioned against allowing a few controversial examples to detract from the sensible approach most schools are taking in protecting allergic students: “There are definitely situations where we see a fear of the allergy that develops far out of proportion to the true risk, but for the vast majority of schools, things are mostly on balance and in perspective” (Sharples, 2009).

It’s important to note that none of the measures such as Sabrina’s Law in Canada or FAAMA in the United States specifically mandates nut-

- Every school board must establish and maintain an anaphylaxis policy.

- School principals must develop individual safety plans for allergic students.

It is up to the individual boards and principals to decide exactly how to implement these directives.

An issue such as this, which pits individual safety against the right of people to eat what they please, will probably never be resolved to everyone’s satisfaction. Opinions are influenced not only by whether one’s child has food allergies, but also by cohort, culture, and personality. Perhaps the best way to close this particular discussion is with a comment from Sabrina Shannon’s mother, Sara.

“We have to make sure this doesn’t happen again,” Sara told an interviewer in regard to Sabrina’s death. “When everything is done, everything is in place, every procedure, every emergency plan, then if a child dies, we can say, ‘There was nothing we could do.’ But when we know there is something we can do to prevent this, we can’t live in a world of denial” (Smith, 2011).

KEY Points

- Young children continue to grow and develop motor skills, eating and playing actively.

- Hazards include eating too much of the wrong foods, environmental chemicals that are linked to diabetes and other health problems later on, and food allergies.

- Young children’s natural energy and sudden curiosity make them vulnerable to injury.

- Primary and secondary prevention of harm begin long before injury, with restrictions on lead and other pollutants (primary) and measures to reduce harm to young children (secondary).