5.3 Thinking During Early Childhood

You have just learned that every year of early childhood brings more advanced motor skills, further brain development, and better control of impulses. All these affect cognition, as first described by Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, already mentioned in Chapter 1.

Piaget: Preoperational Thought

Early childhood is the time of preoperational intelligence, the second of Piaget’s four periods. He called early childhood thinking preoperational because children do not yet use logical operations (reasoning processes) (Inhelder & Piaget, 1964).

However, preoperational children are past sensorimotor intelligence because they can think in symbols, not just senses and motor skills. In symbolic thought, an object or word can stand for something else, including something pretended, or something not seen. For instance, toddlers often hold a block or hairbrush to their ear and pretend they are talking with someone. Symbolic thought allows for the language explosion (detailed later in this chapter), when children can talk about thoughts and memories.

Symbolic thought explains animism, the belief of many young children that natural objects (such as a tree or a cloud) are alive, and that non-

190

Preoperational thought is symbolic and magical, not logical and realistic. Animism gradually disappears as the mind becomes more mature and the child has more experiences of what is real and what is not (Kesselring & Müller, 2011).

Obstacles to LogicPiaget described symbolic thought as characteristic of preoperational thought, and also described four limitations that make logic difficult until about age 6: centration, focus on appearance, static reasoning, and irreversibility.

Centration is the tendency to focus on one aspect of a situation to the exclusion of all others. Young children may, for example, sort blocks by colour (grouping blue blocks together and red ones in another pile). However, if you ask them to sort by colour and shape, putting the blue square blocks together in one pile and the blue triangle blocks in another, and the same for green, they would not be able to do it.

The block example illustrates a particular type of centration that Piaget called egocentrism—literally, “self-

A second characteristic of preoperational thought is a focus on appearance to the exclusion of other attributes. Preschoolers are easily tricked by the outward appearance of things. In preoperational thought, a girl given a short haircut might worry that she has turned into a boy, and young children wearing the hats or shoes of a grown-

Third, preoperational children use static reasoning, believing that the world is unchanging, always in the state in which they currently encounter it. For instance, many children cannot imagine that their own parents were ever children. If they are told that their grandmother is their mother’s mother, they still do not understand that people change with maturation. One preschooler told his grandmother to tell his mother to never spank him, because “she has to do what her mother says.”

The fourth characteristic of preoperational thought is irreversibility. Preoperational thinkers fail to recognize that reversing a process sometimes restores whatever existed before. A young child might cry because her mother put lettuce on her sandwich. Overwhelmed by her desire to have things “just right,” she might reject the food even after the lettuce is removed because she believes that what is done cannot be undone.

ESPECIALLY FOR Early Childhood Teachers How might research on conservation help adults when feeding young children?

Since appearance is crucial, when you are giving drinks to more than one child, all the cups should be the same size. Children will also be happier with two very small crackers rather than one bigger one or with a scoop of ice cream in a small bowl rather than the same-sized scoop in a large one.

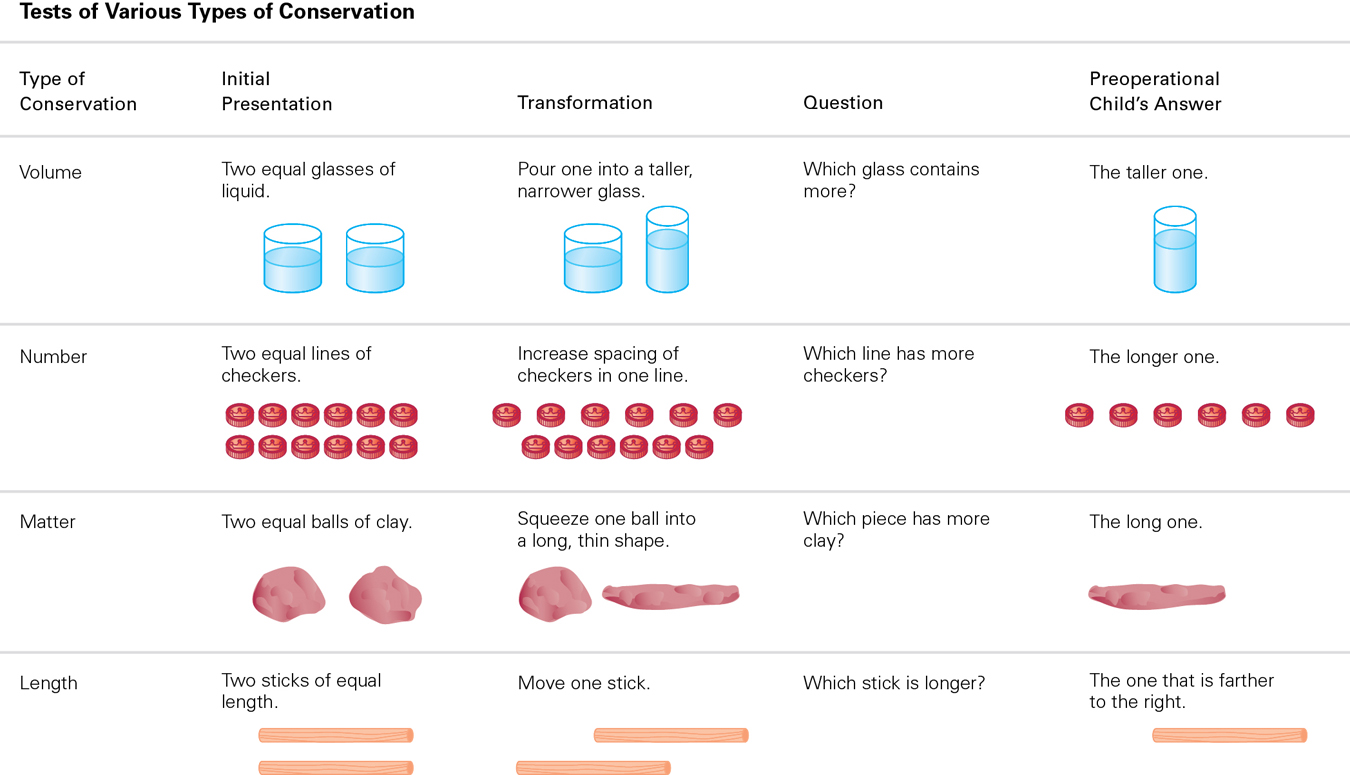

Conservation and LogicPiaget highlighted the many ways in which preoperational intelligence overlooks logic. A famous set of experiments involved conservation, the notion that the amount of something remains the same (is conserved) despite changes in its appearance.

Suppose two identical glasses contain the same amount of milk. If you ask a child to confirm that both glasses have the same amount, he or she will acknowledge that they do. But if you then take one of the glasses of milk and pour the milk into another glass that is taller and thinner, the child will insist that the narrower glass (with the higher level) has more milk. (See Figure 5.5 for other examples.)

All four characteristics of preoperational thought are evident in this mistake. Young children fail to understand conservation of liquids because they focus (centre) on what they see (appearance), noticing only the immediate (static) condition. It does not occur to them that they could reverse the process and re-

191

Piaget’s original tests of conservation required children to respond verbally to an adult’s questions. Later research has found that when the tests of logic are simplified or made playful, young children may succeed. In addition, researchers must consider children’s eye movements or gestures, which may reveal children’s thoughts before they can articulate them in words (Goldin-

As with sensorimotor intelligence in infancy, Piaget underestimated what children could understand. Nonetheless, he was a pioneer in recognizing several crucial ways in which children’s thought patterns are unlike those of adults.

192

Vygotsky: Social Learning

OBSERVATION QUIZ

What three sociocultural factors make it likely that this child will learn?

Motivation (children like to learn new things); human relationships (note the physical touching of father and son); and materials (the long laces make tying them easier).

For decades, the magical, illogical, and self-

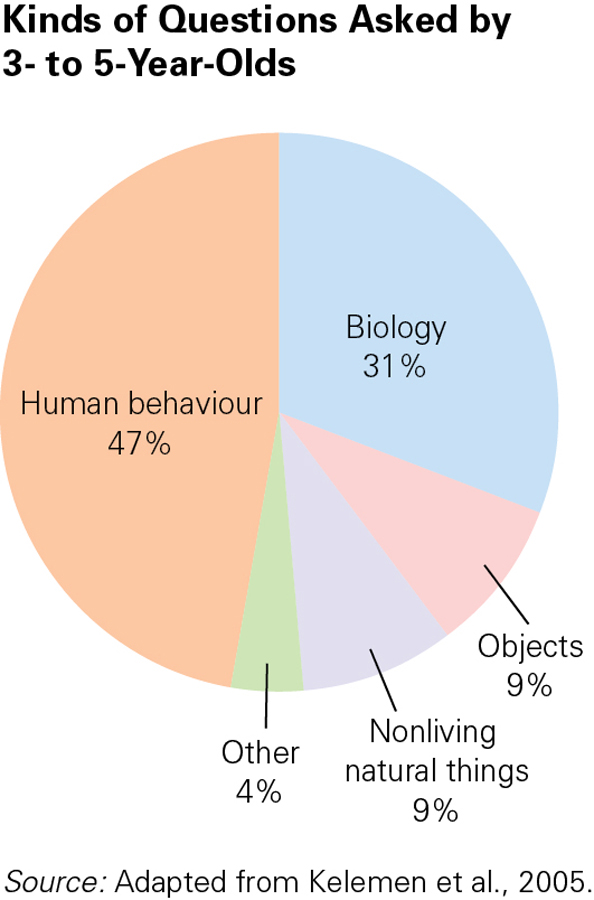

Children and MentorsVygotsky believed that every aspect of children’s cognitive development is embedded in a social context (Vygotsky, 1934/1987). Children are curious and observant. They ask questions—

As you remember from Chapter 1, children learn through guided participation, as older and more skilled mentors teach them. Parents are the first guides, although many teachers, other family members, and peers are mentors as well. For example, the verbal proficiency of children in daycare centres is affected by the language of their playmates, who teach vocabulary without consciously doing so (Mashburn et al., 2009).

According to Vygotsky, children learn because their mentors do the following:

- Present challenges.

- Offer assistance (without taking over).

- Add crucial information.

- Encourage motivation.

Overall, the ability to learn from mentors indicates intelligence, according to Vygotsky: “What children can do with the assistance of others might be in some sense even more indicative of their mental development than what they can do alone” (1934/1987).

Scaffolding and OverimitationVygotsky believed that each individual learns within their zone of proximal development (ZPD), an intellectual arena where new ideas and skills can be mastered. Proximal means “near,” so the ZPD includes the ideas children are close to understanding and the skills they are close to attaining but not yet able to master independently. For example, a parent might hold her child’s hands to help the child walk or hold the back of a bicycle seat as the child learns to ride the bike.

How and when children learn depends, in part, on the wisdom and willingness of mentors to provide scaffolding, or temporary sensitive support, to help them within their developmental zone. Good mentors provide plenty of scaffolding, encouraging children to look both ways before crossing the street (while holding the child’s hand) or letting them stir the cake batter (perhaps the adult’s hand covers the child’s hand on the spoon handle, in guided participation).

Young children also imitate habits and customs that are meaningless, a trait called overimitation, evident in humans but not in other animals. This stems from the child’s eagerness to learn from mentors, allowing “rapid, high-

193

Overimitation was demonstrated in an experiment with 2-

One by one some of the children observed an adult perform irrelevant actions, such as waving a red stick above a box three times and then using that stick to push down a knob to open the box, which could be easily opened by pulling a knob. Then children were given the stick and the box. No matter what their cultural background, the children followed the adult example, waving the stick three times.

ESPECIALLY FOR Teachers Sometimes your students cry, curse, or quit. How would Vygotsky advise you to proceed?

Use guided participation and scaffold the instruction so your students are not overwhelmed. Be sure to provide lots of praise and days of practice. If emotion erupts, do not take it as an attack on you.

Other children did not see the demonstration. When they were given the stick and the box, they simply pulled the knob. Then they observed an adult do the stick-

Children’s Theories

Piaget and Vygotsky recognized that children work to understand their world. No contemporary developmental scientist doubts that. The question now is: When and how do children acquire their impressive knowledge? Part of the answer is that children do not simply gain words, skills, and concepts—

Theory-

We search for causal regularities in the world around us. We are perpetually driven to look for deeper explanations of our experience, and broader and more reliable predictions about it.…Children seem, quite literally, to be born with…the desire to understand the world and the desire to discover how to behave in it.

[Gopnik, 2001]

According to theory-

Exactly how do children seek explanations? They ask questions, and, if not content with the answers, they develop their own theories. This is particularly evident in children’s understanding of God and religion. One child thought his grandpa died because God was lonely; another thought thunder occurred because God rearranged the furniture.

In one study, Mexican-

194

Children seem to wonder about the underlying purpose of whatever they observe, although parents usually respond as if children were seeking scientific explanations. An adult might interpret a child’s “Why?” to mean “What causes X to happen?” when the child intended “Why?” to mean “Tell me more about X” (Leach, 1997).

For example, if a child asks why women have breasts, adults might talk about hormones and maturation, but a child-

A series of experiments further explored when and how 3-

Indeed, even when asked to repeat something ungrammatical that an adult says, children are likely to correct the grammar based on their theory that the adult intended to speak grammatically but failed to do so (Over & Gattis, 2010). This is another example of a general principle: Children develop theories about intentions before they employ their impressive ability to imitate; they do not mindlessly copy whatever they observe.

Theory of MindHuman mental processes—

To know what goes on in another’s mind, people develop a folk psychology, which includes a set of ideas about other people’s thinking called theory of mind. Theory of mind is an emergent ability, slow to develop but typically beginning in most children at about age 4 (Sterck & Begeer, 2010).

ESPECIALLY FOR Social Scientists Can you think of any connection between Piaget’s theory of preoperational thought and 3-

According to Piaget, preschool children focus on appearance and on static conditions (so they cannot mentally reverse a process). Furthermore, they are egocentric, believing that everyone shares their point of view. No wonder they believe that Max would look for the puppy in the blue box instead of in the red one.

Realizing that thoughts do not reflect reality is beyond very young children, but it occurs to them sometime after age 3. They then realize that people can be deliberately deceived or fooled—

In one of several false-

195

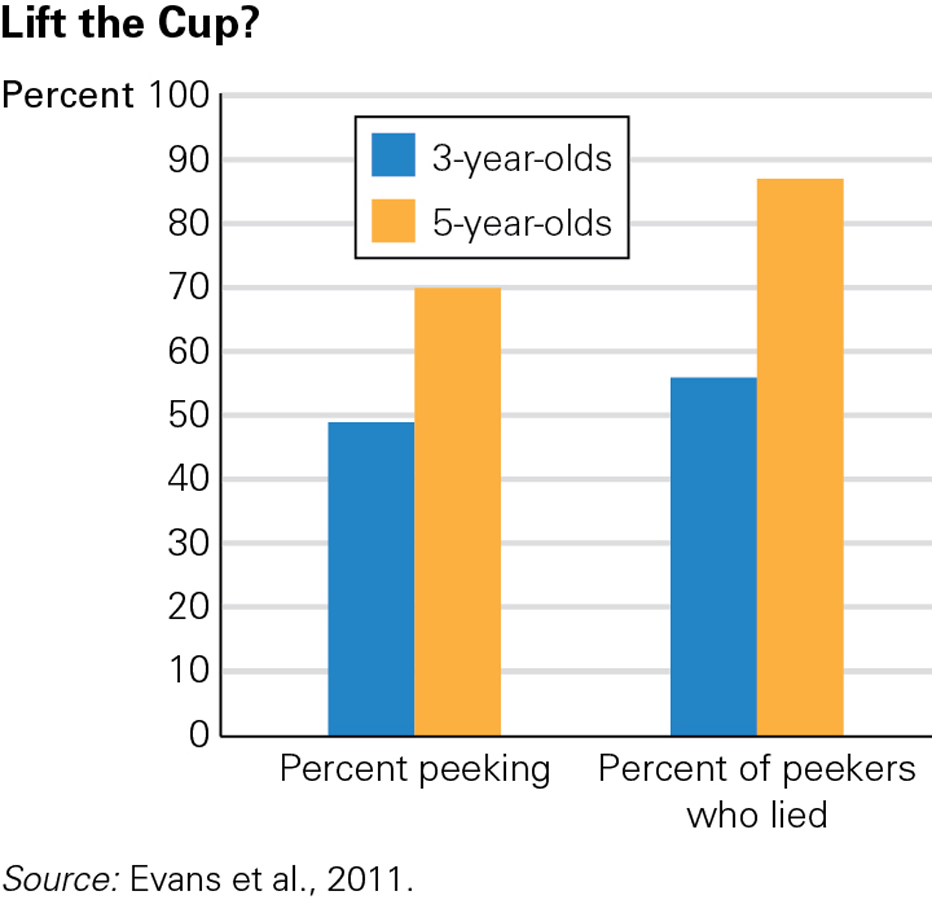

The development of theory of mind can be seen when young children try to escape punishment by lying. Their facial expression often betrays them. Parents sometimes say, “I know when you are lying,” and, to the consternation of most 3-

In one experiment, 247 children, aged 3 and 5, were left alone at a table that had an upside down cup that covered dozens of candies (Evans et al., 2011). The children were told not to peek, but more than half of them did (specifically, 49 percent of the 3-

This particular study was done in Beijing, China, but the results seem universal: Older children are better liars. Beyond the age differences, the experimenters found that the more logical liars were also more advanced in theory of mind and executive functioning (Evans et al., 2011), which indicates a more mature prefrontal cortex (see Figure 5.7).

Brain and Context

Many scientists have found that theory of mind correlates with maturity of the prefrontal cortex and advances in executive processing (Liu et al., 2011; Mar, 2011). The brain connection was further supported by research on 8-

Context and experience are relevant as well (Sterck & Begeer, 2010). Language proficiency helps, especially if mother–

Finally, culture and context matter for theory of mind. A meta-

196

KEY Points

- Piaget believed that preoperational children can use symbolic thought but are illogical and egocentric, limited by appearance and immediate experience.

- Vygotsky realized that children are influenced by their social contexts, including their parents and other mentors and the cultures in which they live.

- In the zone of proximal development, children are ready to move beyond their current understanding, especially if deliberate or inadvertent scaffolding occurs.

- Children use their cognitive abilities to develop theories about their experiences, as is evident in theory of mind, which appears between ages 3 and 5.

- In all of cognitive development, family interactions guide and advance learning.