5.4 Language Learning

Language is the premier cognitive accomplishment of early childhood. Two-

A Sensitive Time

Brain maturation, myelination, scaffolding, and social interaction make early childhood ideal for learning language. As you remember from Chapter 1, scientists once thought that early childhood was a critical period for language learning—

Language in Early Childhood

| Characteristic or Achievement in First Language | Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 years | 3 years | 4 years | 5 years | |

| Vocabulary | 100– |

1000– |

3000– |

5000– |

| Sentence length |

2– |

3– |

5– |

Some seem unending (“… and…who…and…that…and …”) |

| Grammar | Plurals | Conjunctions | Dependent clauses | Complex |

| Pronouns Nouns Verbs Adjectives |

Adverbs Articles |

Tags at sentence end (“… didn’t I?”; “… won’t you?”) | May use passive voice (“Man bitten by dog”) May use subjunctive (“If I were …”) | |

| Questions | “What’s that?” | “Why?” | “Why?” “How?” “When?” |

About social differences (male– |

197

Language learning is an example of dynamic systems, in that every part of the developmental process influences every other part. To be specific, there are “multiple sensitive periods…auditory, phonological, semantic, syntactic, and motor systems, along with the developmental interactions among these components” (Thomas & Johnson, 2008), all of which facilitate language learning.

One of the valuable (and sometimes frustrating) traits of young children is that they talk a lot—

The Vocabulary Explosion

The average child knows about 500 words at age 2 and more than 10 000 at age 6 (Herschensohn, 2007). That’s more than six new words a day. Precise estimates of vocabulary size vary; some children learn four times as many words as others. However, vocabulary always builds quickly and comprehension is more extensive than speech.

Fast-

Language mapping is not precise. For example, children quickly map new animal names close to animal names they already know, without having all the details. Thus, tiger is easy to map if you know lion, but a leopard might be called a tiger. A trip to the zoo facilitates fast-

Fast-

An experiment in teaching the names of parts of objects (e.g., the spigot of a faucet) found that children learned much better if the adults named the object that had the part and then spoke of the object in the possessive (e.g., “See this butterfly? Look, this is the butterfly’s thorax”) (Saylor & Sabbagh, 2004). It is easier to map a new word when it is connected to a familiar one.

198

Words and The Limits of LogicClosely related to fast-

Bilingual children who do not know a word in the language they are speaking often insert a word from the other language. Soon they know who understands which language—

Some words are particularly difficult—

Extensive study of children’s language abilities finds that fast-

Listening, Talking, and ReadingLiteracy is crucial for children. As a result, researchers have conducted studies to discover what activities and practices promote literacy. A meta-

- Code-

focused teaching . In order for children to learn to read, they must “break the code” from spoken to written words. It is helpful for children to learn the letters and sounds of the alphabet (e.g., “A, Alligators all around” or “C is for cat”). - Book-

reading . Vocabulary as well as familiarity with print increase when adults read to children, allowing questions and conversation. - Parent education. When teachers and other professionals teach parents how to stimulate cognition (as in the book-

reading above), children become better readers. - Language enhancement. Within each child’s zone of proximal development, mentors can expand vocabulary and grammar, based on what the child knows and experiences.

- Preschool programs. Children learn from teachers and other children.

Acquiring Basic GrammarWe noted in Chapter 3 that the grammar of language includes the structures, techniques, and rules that are used to communicate meaning. By age 3, children understand the basics. English-

One reason for variation in language learning is that several parts of the brain are involved, each myelinating at a different rate. Further, many genes and alleles affect comprehension and expression. In general, genes affect expressive (spoken or written) language more than receptive (heard or read) language. Thus, some children are relatively talkative or quiet because they inherit that tendency, but experience (not genes) determines what they understand (Kovas et al., 2005).

199

Sometimes children apply the rules of grammar when they should not, an error called overregularization. For example, English-

Learning Two Languages

Canada is a bilingual country with two official languages: English and French. About 58 percent of the total population is anglophone, while about 22 percent is francophone (Corbeil & Blaser, 2009). While most children learn one of the country’s official languages, some receive a bilingual education.

Although there are no official national records on the number of bilingual schools in Canada, it is estimated that about 357 000 students participate in French immersion programs (Allen, 2009). Nationwide, fewer than 10 percent of eligible students are enrolled in French-

ESPECIALLY FOR Immigrant Parents You want your children to be fluent in the language of your family’s new country, even though you do not speak that language well. Should you speak to your children in your native tongue or in the new language?

Children learn by listening, so it is important to speak with them often. You might prefer to read to your children, sing to them, and converse with them primarily in your native language and find a good preschool where they will learn the new language. Try not to restrict speech in either tongue.

Data from the Canadian Youth in Transition Survey, a longitudinal survey designed to study the transitions that youth make between education, training, and work, indicated that by age 21, 29 percent of the participants were bilingual (able to have a conversation in both English and French). However, this differs significantly by mother tongue. Specifically, bilingualism accounts for 65 percent of francophone youth, whereas only 18 percent of non-

Learning two languages is also apparent with language-

Some immigrant school-

200

How and WhySome worry that young children taught two languages might become only semi-lingual, not bilingual, and “at risk for delayed, incomplete, and possibly even impaired language development” (Genesee, 2008). Others argue that “there is absolutely no evidence that children get confused if they learn two languages” (Genesee, 2008). This second position has more research support. Soon after the vocabulary explosion, children who have heard two languages since birth usually master two distinct sets of words and grammar, along with each language’s pauses, pronunciations, intonations, and gestures (Genesee & Nicoladis, 2007).

No doubt early childhood is the best time to learn a language or languages. Neuroscience finds that in young bilingual children, both languages exist in the same areas of their brains, yet they manage to keep them separate in practice. This separation allows them to activate one language and temporarily inhibit the other, experiencing no confusion when they speak to a monolingual person (Crinion et al., 2006). They may be a millisecond slower to respond if they must switch languages, but Canadian researchers have consistently found that their brains function better overall and may even have some resistance to Alzheimer’s disease in old age (Bialystok et al., 2009; Gold et al., 2013).

Another factor that supports young children learning a second language is that it is easier for children to learn the pronunciation of a new language than it is for adults. Although almost all children have pronunciation difficulties even in their first language, they are usually unaware of their mistakes and gradually echo precisely whatever accent they hear. Mispronunciation does not impair fluency since children understand what they are hearing even if they cannot yet pronounce it.

In early childhood, children transpose sounds (magazine becomes mazagine), drop consonants (truck becomes ruck), and convert difficult sounds to easier ones (father becomes fadder). When I was a student teacher for a kindergarten class, the librarian was reading an alphabet book to the class. For each letter, she asked the class to think of other words. When she got to “W,” there was a very long pause. Then a child raised his hand, and said with great excitement, “Wobot!” The whole class cheered and clapped at the excellent answer. Although the answer was wrong (robot), the adults all cheered with the class, too.

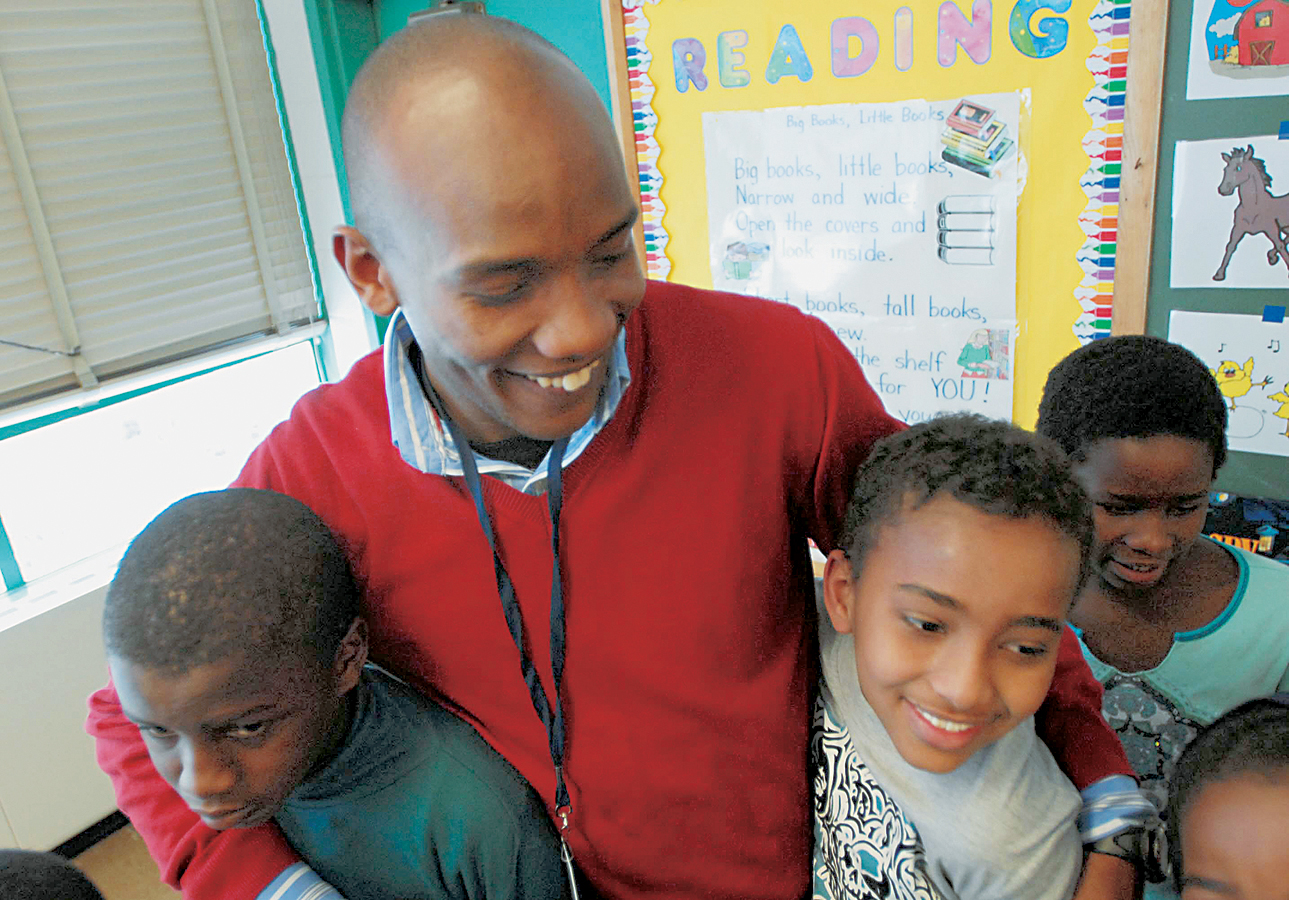

To speak well, young children need to be “bathed in language,” as some early childhood educators express it. They need to listen and speak in every situation, just as a person taking a bath is surrounded by water. Television is a poor teacher because children need personalized, responsive instruction in the zone of proximal development. In fact, young children who watch the most television tend to be delayed in language learning (Harrison & McLeod, 2010).

Language Loss and GainsSchools in all nations stress the dominant language, and language-

Remember that young children are preoperational: They centre on the immediate status of their language (not on its global usefulness or past traditions) and on appearance more than substance. No wonder many shift toward the language of the dominant culture. Since language is integral to culture, if a child is to become fluently bilingual, everyone who speaks with the child should show evident appreciation of both cultures (Pearson, 2008; Snow & Kang, 2006).

201

Becoming a balanced bilingual, speaking two languages so well that no audible hint suggests the other language, is accomplished by millions of young children in many nations, to their cognitive and linguistic benefit (Bialystok & Viswanathan, 2009; Pearson, 2008).Yet language loss is a valid fear. Millions of children either abandon their first language or do not learn the second as well as they might. Although skills in one language can be transferred to benefit the acquisition of another, transfer is not automatic or inevitable (Snow & Kang, 2006). Scaffolding is needed.

The basics of language learning—

Bilingual children and adults are advanced in theory of mind and executive functioning, probably because they need to be more reflective and strategic when they speak. However, sheer linguistic proficiency does not necessarily lead to cognitive advances (Bialystock & Barac, 2012). Simply learning new words and grammar (many preschools teach songs in a second language) does not guarantee a child will learn to understand and appreciate other cultures.

KEY Points

- Children learn language rapidly during early childhood.

- Fast-

mapping is one way children learn. Errors in precision, overregularization, and mispronunciation are common and are not problematic at this age. - Vocabulary advances, particularly if a child is “bathed in language,” hearing many words and concepts.

- Young children can learn two languages almost as easily as one, if adults talk frequently, listen carefully, and value both languages.