6.2 Gender Development

Biology determines whether a child is male or female. As you remember from Chapter 2, at about 8 weeks after conception, the SRY gene on the Y chromosome directs the reproductive organs to develop externally, and then male hormones exert subtle internal control over the brain, body, and later behaviour. Without that SRY gene, the fetus develops female organs, which produce other hormones that affect the brain and behaviour.

It is possible for sex hormones to be unexpressed prenatally, in which case the child does not develop like the typical boy or girl (Hines, 2010). However, that is very rare. Most children are male or female in all three ways: chromosomes, genitals, and hormones. That is their nature, but obviously nurture affects their sexual development from birth until death.

217

During early childhood, sex patterns and preferences become important to children and apparent to adults. At age 2, children consistently apply gender labels (Ms., Mr., boy, girl). By age 4, children are convinced that certain toys (such as dolls or trucks) and roles (not just Daddy or Mommy, but also nurse, teacher, police officer, and soldier) are best for one sex or the other. Dynamic systems theory helps us realize that such preferences are affected by many developmental aspects of biology and culture, changing as humans grow older (Martin & Ruble, 2010).

Sex and Gender

Scientists distinguish sex differences, which are biological differences between males and females, from gender differences, which are culturally prescribed roles and behaviours. In theory, this seems straightforward, but as with every nature–

Many studies in different countries, including Kenya, Nepal, Belize, and Samoa, have found that children undergo three stages in understanding gender (Munroe et al., 1984). The first stage is reached in the first year of life. During this first year, infants can make gender distinctions, correctly labelling themselves as a boy or girl, as well as labelling the gender of others. This first step is called gender identity.

DESIGN PICS/DANITADELIMONT.COM

But, being able to identify one’s gender does not mean that toddlers have a full understanding of gender. For example, one little girl said she would grow a penis when she got older, and one little boy offered to buy his mother one. Ignorance about biology was demonstrated by a 3-

At about age 4, children reach the next step, gender stability. At this stage, children believe that a person will stay the same gender over his or her lifetime (Slaby & Frey, 1975). However, children at this age do not understand that gender is independent of physical appearance, such as type of clothing or haircut. They think that a girl who looks like a boy has become a boy, and vice versa.

218

When children truly believe that gender cannot change, regardless of outward appearances, they have reached the final stage, gender constancy. This occurs around the age of 5 or 6, similar to when children also have an understanding of conservation.

Theories of Gender Development

In recent years, sex and gender issues have become increasingly complex. Individuals may be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, mostly straight, or totally heterosexual (Thompson & Morgan, 2008). But around age 5 many children are quite rigid in their ideas of male and female. Already by age 3, most boys reject pink toys and most girls prefer them (LoBue & DeLoache, 2011). In early childhood programs, girls tend to play with girls, and boys with boys. Despite their parents’ and teachers’ wishes, children say, “No girls [or boys] allowed.”

A dynamic systems approach reminds us that attitudes, roles, and even the biology of gender differences and similarities change from one developmental period to the next; theories about how and why this occurs change as well (Martin & Ruble, 2010). Nonetheless, it is useful to review the six theories described in Chapter 1 to understand the range of explanations for the apparent sexism of many 5-

Psychoanalytic TheoryFreud (1938) called the period from about ages 3 to 6 the phallic stage, named after the phallus, the Greek word for “penis.” At about 3 or 4 years of age, said Freud, boys become aware of their male sexual organ. They masturbate, fear castration, and develop sexual feelings toward their mother. This makes every young boy jealous of his father—

Freud believed that this ancient story dramatizes emotions that all boys feel about their parents—

Freud offered several descriptions of the moral development of girls. One centres on the Electra complex (also named after a figure in classical mythology). The Electra complex is similar to the Oedipus complex in that the little girl wants to eliminate the same-

According to psychoanalytic theory, at the phallic stage children cope with guilt and fear through identification; that is, they try to become like the same-

Many social scientists from the mid-

219

It began with a conversation with my eldest daughter, Bethany, when she was about 4 years old:

Bethany: When I grow up, I’m going to marry Daddy.

Me: But Daddy’s married to me.

Bethany: That’s all right. When I grow up, you’ll probably be dead.

Me: [Determined to stick up for myself] Daddy’s older than me, so when I’m dead, he’ll probably be dead, too.

Bethany: That’s OK. I’ll marry him when he gets born again.

I was dumbfounded, without a good reply. I had no idea where she had gotten the concept of reincarnation. Bethany saw my face fall, and she took pity on me:

Bethany: Don’t worry, Mommy. After you get born again, you can be our baby.

The second episode was a conversation I had with my daughter Rachel when she was about 5:

Rachel: When I get married, I’m going to marry Daddy.

Me: Daddy’s already married to me.

Rachel: [With the joy of having discovered a wonderful solution] Then we can have a double wedding!

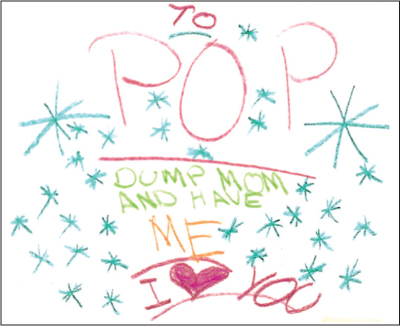

The third episode took the form of a “valentine” left on my husband’s pillow on February 14th by my daughter Elissa (see image). Finally, when my youngest daughter Sarah, turned 5, she also said she would marry my husband. I told her she couldn’t, because he was married to me. Her response revealed one more hazard of watching TV: “Oh, yes, a man can have two wives. I saw it on television.”

A single example (or four daughters) does not prove that Freud was correct. But his theory may have some merit, as seen in the previous anecdotes.

Other Theories of Sex-

Learning theory teaches that virtually all roles, values, and behaviours are learned. To behaviourists, gender distinctions are the product of ongoing reinforcement and punishment, as well as social learning. Parents, peers, and teachers tend to reward behaviour that is “gender appropriate” more than behaviour that is “gender inappropriate” (Berenbaum et al., 2008). For example, adults compliment a girl when she wears a dress but not when she wears pants (Ruble et al., 2006), and a boy who asks for a train and a doll for his birthday is more likely to get the train. Boys are rewarded for boyish requests, not for girlish ones.

According to social learning theory, children model themselves after people they perceive to be nurturing, powerful, and yet similar to themselves. For young children, those people are usually their parents. As it happens, adults are the most sex-

Furthermore, although national or provincial/territorial policies (e.g., subsidizing preschool) have an effect on gender roles, and many fathers are involved caregivers, in every nation women do much more child care, housecleaning, and meal preparation than men do (Hook, 2010). Children follow those examples, unaware that the examples they see are caused partly by their very existence: Before children are born, many couples share domestic work.

220

Cognitive theory offers an alternative explanation for the strong gender identity that becomes apparent at about age 5. Remember that cognitive theorists focus on how children understand various ideas. A gender schema is the child’s understanding of gender differences in the context of the gender norms and expectations of their culture (Kohlberg et al., 1983; Martin et al., 2011; Renk et al., 2006). Young children have many gender-

Furthermore, as children try to make sense of their culture, they encounter numerous customs, taboos, and terminologies that enforce gender norms. Remember that for preoperational children, appearance is crucial. When they see men and women cut their hair, use cosmetics, and dress in distinct, gender-

Systems theory teaches that mothers and fathers play an important role in developing their children’s understanding of gender. The clothing colours that parents pick for their sons (usually blue) or daughters (usually pink and purple), the toys they buy them, and the activities they teach them provide clues about how to behave. If fathers are more traditional (acting as the primary breadwinner and expecting their wives to take care of the children), they may not do any of the cooking, cleaning, or caregiving. They may also teach their sons to behave in a similar fashion and insist that their daughters help the mother. On the other hand, fathers who share the household chores and caregiving duties with their spouses are more likely to have daughters who are not limited by gender roles in choosing a career.

Humanism stresses the hierarchy of needs, beginning with survival, then safety, then love and belonging. The final two—

In a study of slightly older children, participants wanted to be identified as male or female, not because they disliked the other sex, but because same-

Evolutionary theory holds that sexual attraction is crucial for humankind’s most basic urge, to reproduce. For this reason, males and females try to look attractive to the other sex, walking, talking, and laughing in gendered ways. If girls see their mothers wearing makeup and high heels, they want to do likewise. According to evolutionary theory, the species’ need to reproduce is part of everyone’s genetic impulses, so young boys and girls practise becoming attractive to the other sex. This ensures that they will be ready after puberty to find each other, and a new generation will be born.

What is Best?Each of the major developmental theories strives to explain the sex and gender roles that young children express, but no consensus has been reached (as we saw was the case with emotional regulation in this chapter and language development in Chapter 5). The theories all raise important questions: What gender patterns should parents and caregivers teach? Should every child learn to combine the best masculine and feminine characteristics (called androgyny), thereby causing gender stereotypes to eventually disappear as children become more mature, as happens with their belief in Santa Claus and the tooth fairy? Or should male–

221

KEY Points

- Sex differences are biological differences between males and females, while gender differences are culturally prescribed roles and behaviours.

- Young children learn gender identify during the first year of life; however, they do not have a full understanding of gender until later.

- Theorists refer to attitudes, roles, and biology to explain sex-

role development.