6.4 The Role of Caregivers

We have seen that young children’s emotions and actions are affected by many factors, including brain maturation, culture, and peers. Now we focus on another primary influence on young children: their caregivers.

All children need parents who care about them because, no matter what the parenting style, parental involvement plays an important role in the development of both social and cognitive competence (Parke & Buriel, 2006). As more and more children spend long hours during early childhood with other adults, alternate caregivers become pivotal as well.

Caregiving Styles

Although thousands of researchers have traced the effects of parenting on child development, the work of one person, more than 50 years ago, continues to be influential. In her original research, Diana Baumrind (1967, 1971) studied 100 preschool children, all from California and almost all middle-

Baumrind found that parents differed on four important dimensions:

- Expressions of warmth. Some parents are warm and affectionate; others, cold and critical.

- Strategies for discipline. Parents vary in how they explain, criticize, persuade, and punish.

- Communication. Some parents listen patiently; others demand silence.

- Expectations for maturity. Parents vary in how much responsibility and self-

control they expect.

Baumrind’s Four Styles of CaregivingOn the basis of the dimensions listed above, Baumrind identified four parenting styles (summarized in TABLE 6.1).

| Communication | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Style | Warmth | Discipline | Expectations of Maturity | Parent to Child | Child to Parent |

| Authoritarian | Low | Strict, often physical | High | High | Low |

| Permissive | High | Rare | Low | Low | High |

| Authoritative | High | Moderate, with much discussion | Moderate | High | High |

| Neglecting- |

Low | Rare | Low | Low | Low |

- Authoritarian parenting. The authoritarian parent’s word is law (e.g., my way or the highway) and not to be questioned. Misconduct brings strict punishment, usually physical. Authoritarian parents set down clear rules and hold high standards. They do not expect children to offer opinions; discussion about emotions is especially rare. (One adult from such a family said that “How do you feel?” had only two possible answers: “Fine” and “Tired.”) Authoritarian parents seem cold, rarely showing affection.

228

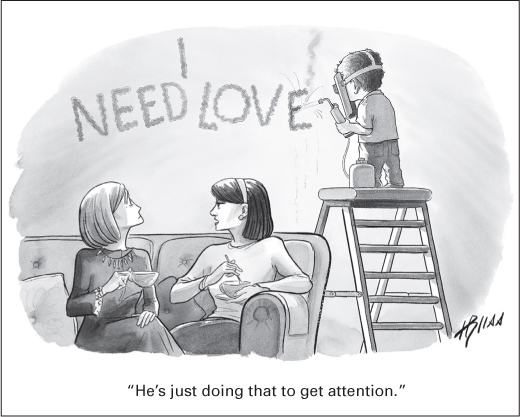

- Permissive parenting. Permissive parents (also called indulgent parents) make few demands, hiding any impatience they feel. Discipline is lax, partly because they have low expectations for maturity. Instead, permissive parents are highly nurturing and accepting, listening to whatever their offspring say, and supporting their decisions.

- Authoritative parenting. Authoritative parents set limits, but they are flexible. They encourage maturity, but they usually listen and forgive (not punish) if the child falls short. There is verbal give-

and- take, taking the child’s interests and opinions into consideration. Authoritative parents consider themselves as kind but firm guides, not authorities (like authoritarian parents) and not friends (like permissive parents).

- Rejecting-neglecting parenting. Rejecting-

neglecting parents are disengaged, neither demanding nor responsive. Neglectful parents are unaware of their children’s behaviour; they seem not to care. They have low expectations, and do not monitor or support their children. They may actively reject their children, or else entirely neglect their parenting responsibilities.

The following long-

- Authoritarian parents raise children who become conscientious, obedient, and quiet but not especially happy. Such children tend to feel guilty or depressed, internalizing their frustrations and blaming themselves when things don’t go well. As adolescents, they sometimes rebel, leaving home before age 20.

- Permissive parents raise unhappy children who lack self-

control, especially in the give- and- take of peer relationships. Inadequate emotional regulation makes them immature and impedes friendships, which is the main reason for their unhappiness. They tend to continue to live at home, still dependent, in early adulthood. - Authoritative parents raise children who are successful, articulate, happy with themselves, and generous with others. These children are usually liked by teachers and peers, especially in cultures that value individual initiative (e.g., North America).

- Rejecting-

neglecting parents raise children who are immature, sad, lonely, and at risk of injury and abuse.

Problems With Baumrind’s StylesBaumrmd’s classification is often criticized. Problems include the following:

- Her participants were not diverse in SES, ethnicity, or culture.

- She focused more on adult attitudes than on adult actions.

- She overlooked children’s temperament, which affects the adult’s parenting style.

- Her classifications did not capture the complexities of parenting; for example, she did not recognize that some “authoritarian” parents are also affectionate.

- Her classifications were mutually exclusive, but in reality parents use various “types” of parenting, depending on the situation at hand.

- She did not realize that some “permissive” parents provide extensive verbal guidance.

229

We now know that children’s temperament and the culture’s standards powerfully affect caregivers, as do the consequences of parenting style (Cipriano & Stifter, 2010).

Moving beyond Baumrind’s dimensions, University of Toronto researchers Maayan Davidov and Joan Grusec (2006) focused on two features of positive parenting—

Also focusing on the emotional dimensions of parenting, Janet Strayer and William Roberts (2004) found that Canadian children were more likely to be angrier with mothers and fathers who were less empathic and warm, and had more age-

Such studies suggest that certain aspects of parenting, like responsiveness to the child’s distress and who the parent is (e.g., mother, father), can make unique contributions to the child’s development.

Cultural Variations

The significance of context is particularly obvious when children of various ethnic groups are compared. It may be that certain alleles are more common in children of one group or another, and that affects their temperament. However, much more influential are the attitudes and actions of adult caregivers. As Kagicibasi (1996) argued, children from more interdependent cultures, where relationships and the group’s needs are placed ahead of individual needs, may interpret high parental control as normal, and not as rejecting or harsh.

Parental InfluenceNorth American parents of Chinese, Caribbean, or African heritage are often stricter, or more authoritarian, than those of European backgrounds, yet their children develop better than if the parents were easygoing (Chao, 2001; Parke & Buriel, 2006). Latino parents are sometimes thought to be too intrusive, other times too permissive—

In 1995, Chao examined Chinese-

230

In another study of 1477 instances in which Mexican-

Hailey [a 4-

[Livas-

Note that the mother’s first three efforts failed, and then a look accompanied by an inaccurate explanation (in that setting, no one could be hurt) succeeded. The researchers explained that these Mexican-

A study in Hong Kong found that almost all parents believed that young children need strong guidance, including physical punishment. But most classified themselves as authoritative, not authoritarian, because they listened to their children and adjusted their expectations when needed (Chan et al., 2009).

A multicultural study of Canadian parents used parent and teacher ratings of child behaviour to determine if there were cultural differences in terms of parenting and child behaviour. Using teacher ratings of student behaviour, parental harshness was positively related to child aggression in European-

In general, multicultural and international research has found that particular discipline methods and family rules are less important than warmth, support, and concern. Children from every ethnic group and every country benefit if they believe that they are appreciated; children everywhere suffer if they feel rejected and unwanted (Gershoff et al., 2010; Khaleque & Rohner, 2002).

231

Given a multicultural and multicontextual perspective, developmentalists hesitate to recommend any particular parenting style (Dishion & Bullock, 2002; J. G. Miller, 2004). That does not mean that all families function equally well—

What About Teachers?When Baumrind did her original research, 2-

Although all four styles are possible for caregivers who watch only one child, almost no teacher is permissive or neglectful. They couldn’t be. Allowing a group of 2-

However, teachers can be authoritarian, setting down the law with no exceptions, or authoritative, setting flexible guidelines. Teachers with more education tend to be authoritative, responding to each child, listening and encouraging language, and so on. This fosters more capable children, which is one reason why teacher education is a measure used to indicate the quality of educational programs (Barnett et al., 2010; Norris, 2010).

In general, young children learn more from authoritative teachers because the teachers are perceived as warmer and more loving. In fact, one study found that, compared with children who had authoritarian teachers, those children whose teachers were child-

KEY Points

- Baumrind identified four styles of caregiving: authoritarian, permissive, authoritative, and rejecting-

neglecting. Each of these styles has specific effects on child development. - Parenting styles differ according to the child’s temperament and cultural variations.

- Teaching style and the caregiving style of daycare providers can also affect child development.