7.1 Health and Sickness

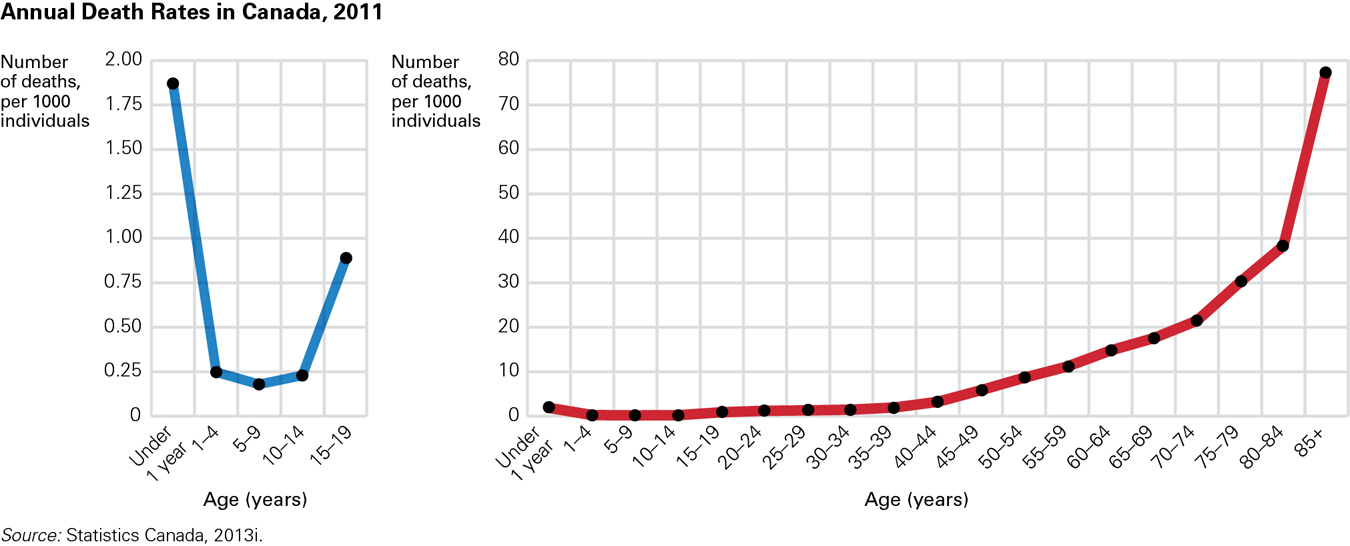

Genetic and environmental factors safeguard middle childhood (about ages 6 to 11 years), the period after early childhood and before adolescence. One explanation comes from the evolutionary perspective: Genes protect children who have already survived the hazards of birth and early childhood so they can live long enough to reproduce (Konner, 2010). This evolutionary explanation may not be accurate, but for whatever reason, fewer fatal diseases or accidents resulting in death occur from age 6 to age 11 than at any other period of life (see Figure 7.1).

Slower Growth, Greater Strength

Unlike infants or adolescents, school-

Muscles, including the heart and lungs, become strong. With each passing year, children can run faster and exercise longer (Malina et al., 2004). As long as school-

Medical Care

Immunization has reduced deaths dramatically, and throughout childhood, lethal accidents and fatal illnesses are far less common than a few years ago. For example, in Canada, before immunizations were introduced, about 9000 people, many of them young children, contracted diphtheria over any given five-

251

Furthermore, better medical care (diagnostic and preventative) has meant fewer children suffer with chronic conditions such as hearing impairments or anemia—

For all children, establishing good health habits in childhood protects health in adolescence and adulthood. This is especially important for children with serious, chronic conditions (such as diabetes, phenylketonuria [PKU], epilepsy, cancer, asthma, and sickle-

Unfortunately, children in poor health for economic or social reasons are vulnerable throughout their lives. For low-

Physical Activity

The level of physical activity of children in middle childhood affects both their mental and physical health. The Health Behaviour in School-

Ian Janssen from Queen’s University, Ontario, and his international collaborators examined the data from an earlier version of this study. They found that lower physical activity and a greater amount of time spent watching television were associated with a greater likelihood of becoming overweight (Janssen et al., 2005).

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Why do you think that level of physical activity decreases after age 11?

Older children tend to spend more time on screen-

Beyond the sheer fun of playing, some benefits of physical activity are immediate. For example, a Canadian study found that 6-

- better overall health

- less obesity

- appreciation of cooperation and fair play, especially when playing games with rules

- improved problem-

solving abilities - respect for teammates and opponents of many ethnicities and nationalities.

252

Playing sports during middle childhood also has risks:

- loss of self-

esteem (teammates and coaches are sometimes cruel) - injuries (sometimes serious, including concussions)

- reinforcement of prejudices (especially against the other sex)

- increased stress (evidenced by altered hormone levels, insomnia).

Where can children reap the benefits and avoid the hazards of active play? There are three possibilities: neighbourhoods, schools, and sports leagues.

Neighbourhood GamesNeighbourhood play is flexible. Rules and boundaries are adapted to the context (out of bounds is “past the tree” or “behind the parked truck”). Street hockey, touch football, tag, hide-

Children play tag, hide and seek, or pickup basketball. They compete with one another but always according to rules, and rules that they enforce themselves without recourse to an impartial judge. The penalty for not playing by the rules is not playing, that is, social exclusion. …

[Gillespie, 2010]

Unfortunately, “not playing” is not only a consequence of ignoring the rules, but also of not having the time or a place to play. Parks and empty fields are increasingly scarce. A century ago, 90 percent of the world’s children lived in rural areas; now most live in cities or at the city’s edge.

ESPECIALLY FOR Physical Education Teachers A group of parents of Grade 4 and 5 students has asked for your help in persuading the school administration to sponsor a competitive sports team. How should you advise the group to proceed?

Discuss with the parents their reasons for wanting the team. Children need physical activity, but some aspects of competitive sports are better suited to adolescents and adults than to children.

To make matters worse, many parents keep their children inside because they fear “stranger danger”—although one expert writes that “there is a much greater chance that your child is going to be dangerously overweight from staying inside than that he is going to be abducted” (quoted in Layden, 2004). Homework and video games compete with outdoor play, especially in North America. According to an Australian scholar,

Australian children are lucky. Here the dominant view is that children’s after school time is leisure time. In the United States, it seems that leisure time is available to fewer and fewer children. If a child performs poorly in school, recreation time rapidly becomes remediation time. For high achievers, after school time is often spent in academic enrichment.

[Vered, 2008]

Canada and the United States are not the worst-

Organized SportSchools in North America often have after-

253

Paradoxically, school exercise may actually improve academic achievement (Carlson et al., 2008), partly because of the increased blood flow to the brain. The Centers for Disease Control recommends that children be active (i.e., not sit on the sidelines awaiting a turn) for at least half of the time in their physical education classes (Khan et al., 2009). Many schools do not reach this goal.

About 75 percent of Canadian children engage in organized sports or physical activities (CFLRI, 2011a). The organized sport that parents sign their children up for varies depending on the family’s culture and socioeconomic status. For example, some children join hockey leagues, others learn to play basketball or soccer, and others take karate or swimming lessons.

Unfortunately, children from low-

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Canadian Kids Get an “F” in Physical Activity

In the past several years, many scientific studies have established strong links between physical activity in middle childhood and the improved functioning of young bodies and minds (Bürgi et al., 2011; Davis et al., 2007). Demonstrated benefits include

- improved motor skills

- better aerobic fitness

- improved cognitive functions

- higher self-

esteem.

Specifically, moderate to intense levels of physical activity have been shown to lower blood pressure and reduce body fat. Physically active children also appear to experience fewer problems with their mental health (Biddle & Asare, 2011).

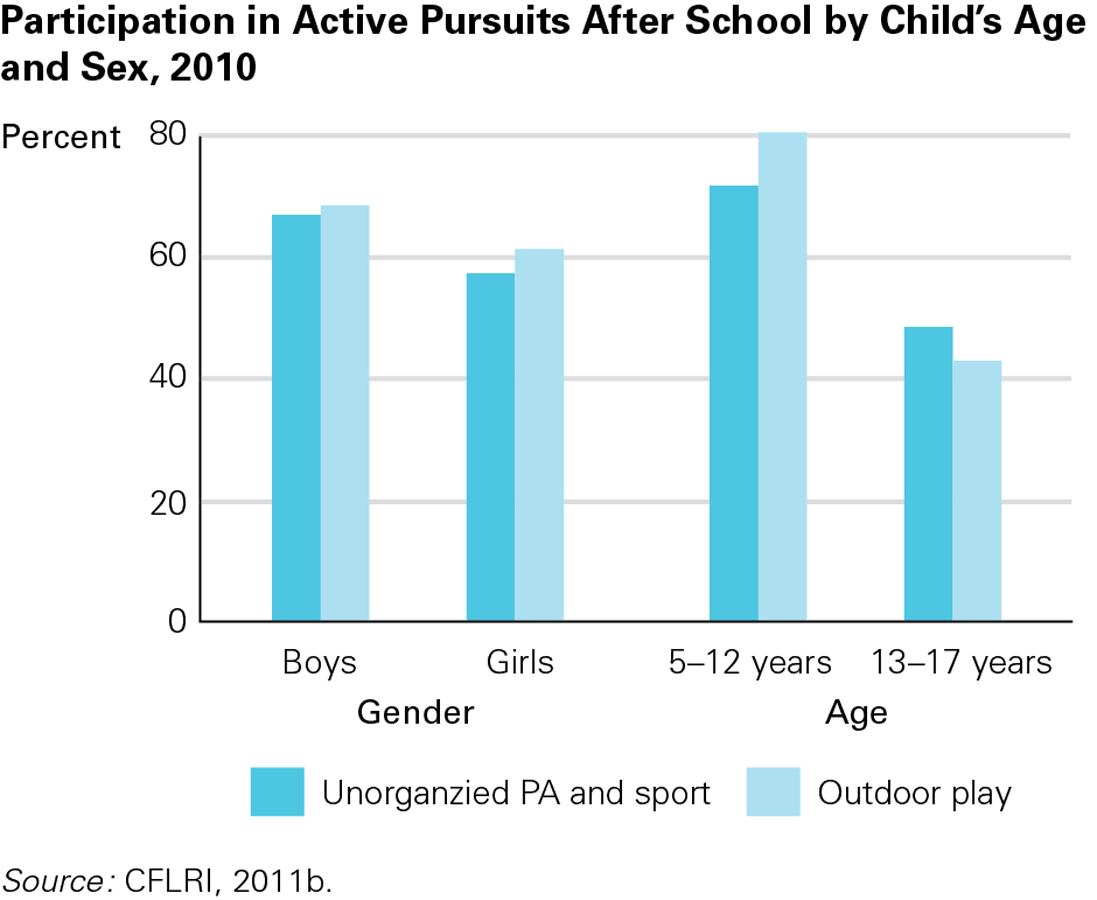

With these proven benefits in mind, it is alarming that researchers have also documented steep declines over the last 50 years in physical activity levels among children in Canada and other countries. For example, data from the research organization Active Healthy Kids Canada (AHKC) show that from 2000 to 2010, the number of children who played outside after school dropped by 14 percent (AHKC, 2012b). The Canadian Fitness & Lifestyle Research Institute (2011b) reported that in 2010, outdoor play was greater among boys than girls, and almost twice as high among 5-

Health Canada and the World Health Organization both recommend that 5-

AHKC issues an annual bulletin in the form of a report card on activity levels of Canadian children. In 2012, the news was so dismal that AHKC entitled its report Is Active Play Extinct? and illustrated it with photographs of dinosaur skeletons juxtaposed with such childhood relics as paddle balls, skipping ropes, and hula hoops. For the sixth straight year, AHKC assigned Canadian children a grade of “F” in the category of physical activity (AHKC, 2012b).

254

The data reported do indeed tell a grim story. Only 7 percent of Canadian children get the recommended 60 minutes of physical activity a day. This means the vast majority—

What has caused this remarkable falling off in activity levels among Canadian schoolchildren? According to the AHKC report, the two main reasons are

- safety concerns that lead to overprotective parenting

- dramatic increases in screen time for children and youth.

Even though Canadian crime rates are no higher today than in the 1970s, parents are more aware of cases of child assault and abduction due to greater media exposure (AHKC, 2012a; Silver, 2007). As a result, many parents have developed a “better safe than sorry” attitude. Whereas in past decades they allowed their children to play unsupervised for hours in empty lots or neighbourhood parks, today’s parents take a much more cautious approach, encouraging their children to stay inside where they are easier to monitor.

Children’s attraction to screen time means that most are only too happy to comply with the wishes of overly protective parents. One study indicates that Canadian children in Grades 6 to 12 spend an average of 7 hours and 48 minutes a day in front of the screens of their computers, televisions, video games, and smart phones (Leatherdale & Ahmed, 2011).

The result of parental worries over safety and their children’s fascination with electronic media is that Canadian kids spend about 63 percent of their free time being sedentary, getting no exercise at all. In fact, on weekends, when they have an abundance of time to spend as they please, they are actually less active than during the week (Garriguet & Colley, 2012).

Both AHKC (2012b) and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (2011) make a number of recommendations that they hope will reverse declining rates of physical activity among children:

- Provide greater access to playing fields, natural areas, and parks, along with equipment such as balls and skipping ropes to encourage active play.

- Encourage children to engage in modes of active transportation such as walking, cycling, and in-

line skating or skateboarding. Facilitate this through improvements to sidewalks, bike lanes, and pedestrian crosswalks. - Support school environments that encourage healthy activity through physical education programs.

- Put in place household rules and limits to discourage excessive amounts of screen time, and provide time for active sport and play.

As Dr. Mark Tremblay, director of the Healthy Active Living and Obesity Research Group at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, noted, all children, regardless of age, should be engaged in regular forms of active play, where they can run, climb, jump, or cartwheel in open and safe places with their friends, like their parents once did. Active play not only improves children’s motor function, but also their levels of creativity, decision making, problem solving, and social skills (AHKC, 2012a).

Health Problems

Although few children are seriously ill during middle childhood, many have at least one chronic condition that might interfere with school, play, or friendship. Individual, family, and contextual influences interact with one another in the causes and treatments of every illness. To illustrate the dynamic interactions of every health condition, we focus on two examples: obesity and asthma.

255

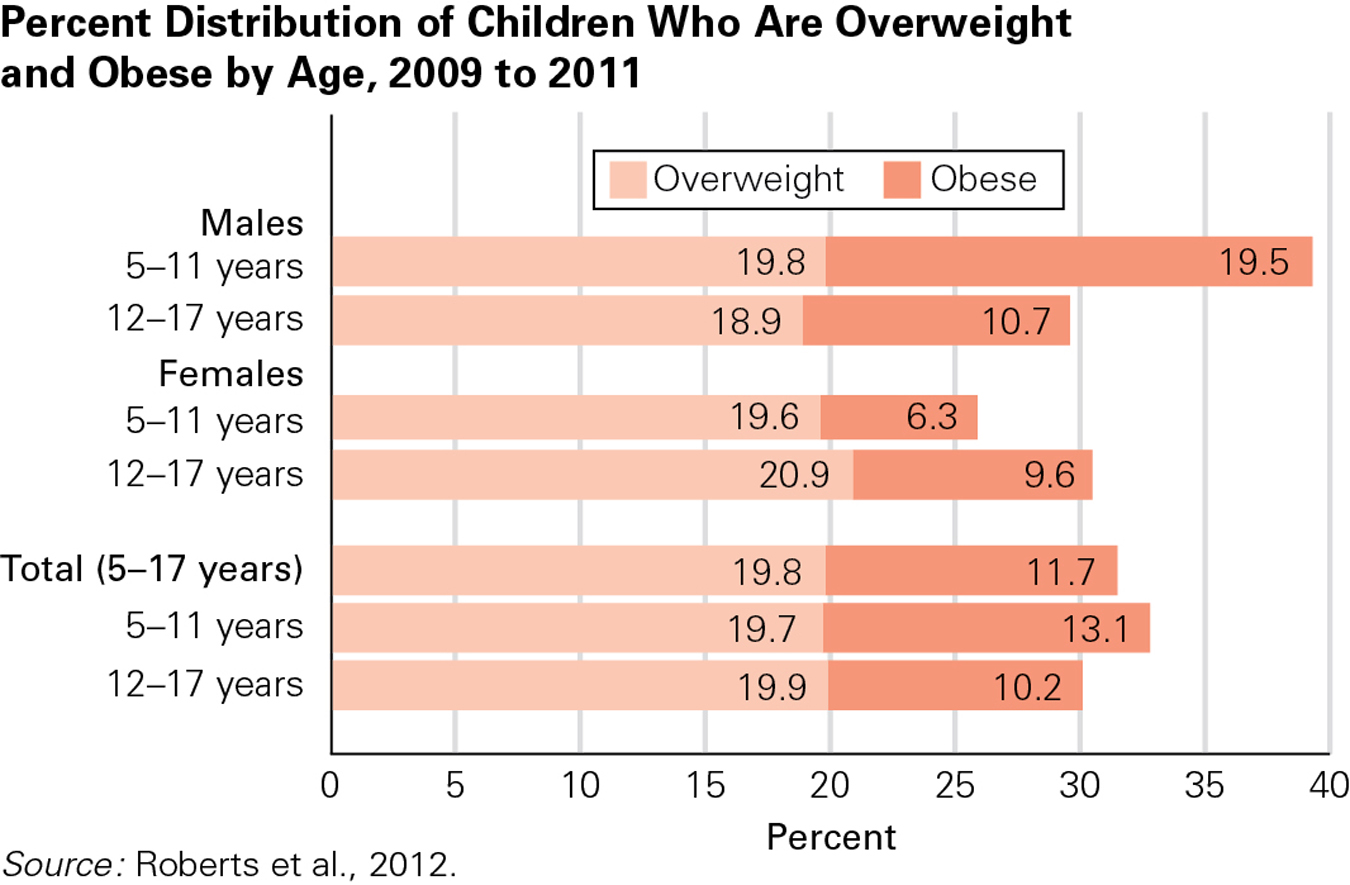

Childhood ObesityBody mass index (BMI), as mentioned in Chapter 5, is the ratio of weight to height. Childhood overweight is usually defined as having a BMI above the 85th percentile, and childhood obesity as having a BMI above the 95th percentile of children of the same age (Barlow & the Expert Committee, 2007).

Childhood obesity is increasing worldwide, having more than doubled since 1980 in all three nations of North America (Canada, the United States, and Mexico) (Ogden et al., 2011). Statistics Canada reports that about one-

Childhood obesity is linked to asthma, high blood pressure, and elevated cholesterol (especially LDL, the “lousy” cholesterol). According to the Canadian Diabetes Association (2012), 95 percent of children with Type 2 diabetes—

There are hundreds if not thousands of contributing factors for childhood obesity, from the cells of the body to the norms of the society (Harrison et al., 2011). More than 200 genes affect weight by influencing activity level, food preference, body type, and metabolism (Gluckman & Hanson, 2006). Having two copies of an allele called FTO increases the likelihood of both obesity and diabetes (Frayling et al., 2007).

But we cannot solely blame genes for today’s increased obesity, since genes change little from one generation to the next (Harrison et al., 2011). Rather, family practices and eating habits have changed. Obesity is more common in infants who are not breastfed, in preschoolers who watch TV and drink soft drinks, and in school-

ESPECIALLY FOR Teachers You are concerned about a child in your class who is overweight. What can you do to help?

You could incorporate lessons about healthy snacks and exercise levels into the school day for the whole class so the child doesn’t feel singled out. Children who learn about health from their teachers may then ask their parents for opportunities to exercise, to join a sports team, and so on.

During middle childhood, children themselves may contribute to their weight gain by pestering parents for calorie-

One particular culprit is advertising for candy, cereal, and fast food (Linn & Novosat, 2008); the rate of childhood obesity correlates with how often children see food commercials (Lobstein & Dibb, 2005). As one researcher at the Université du Québec à Montréal reported, the various advertising strategies used by companies have increased children’s temptation as marketers have given products effective appeal—

Since every system (bio-

256

BLOOM IMAGE/GETTY IMAGES

Rather than trying to zero in on any single factor, a dynamic-

AsthmaAsthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways that makes breathing difficult. Although asthma affects people of every age, rates are highest among school-

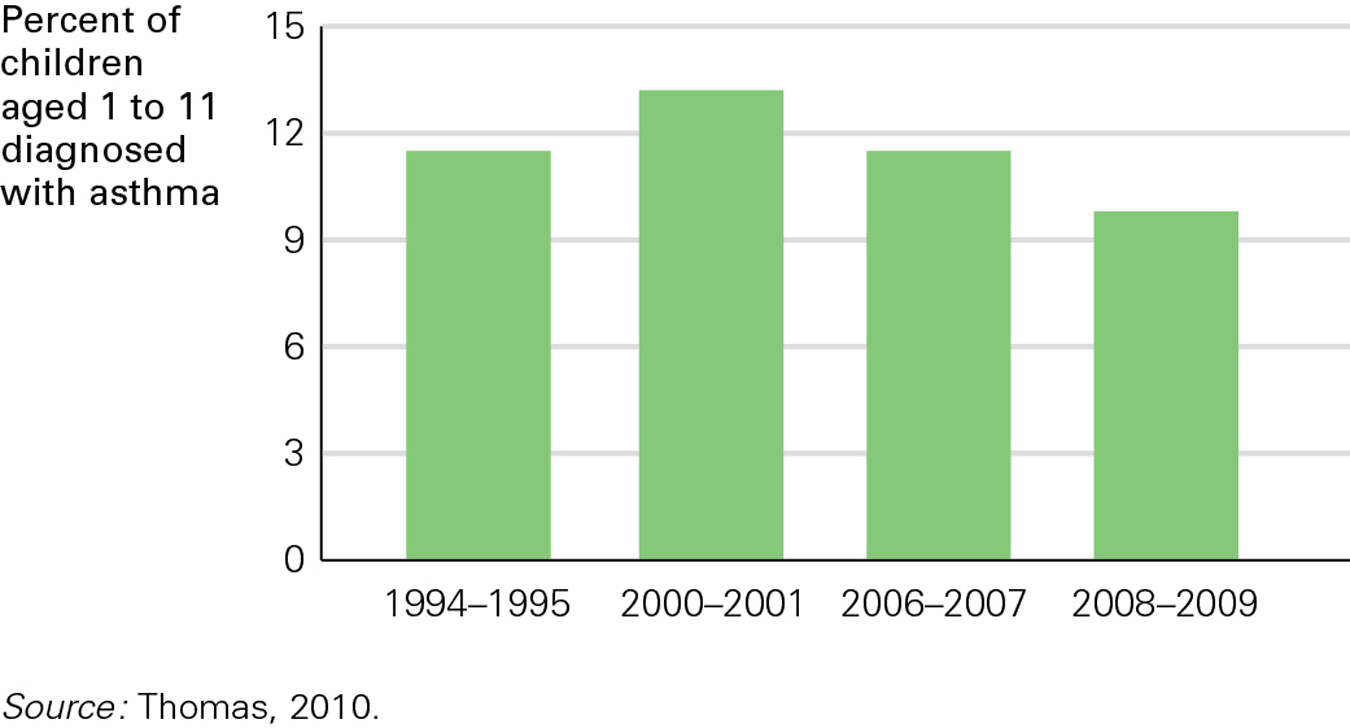

In Canada, asthma is one of the most common chronic childhood diseases (Garner & Kohen, 2008). After increasing steadily for several decades, the childhood asthma rate in Canada has levelled off and even declined slightly over the past few years (see Figure 7.4). Statistics Canada reports that asthma rates for children between the ages of 2 and 7 years rose from 11 percent in 1995 to as high as 13 percent in 2001, but then fell to 10 percent in 2009 (Thomas, 2010).

Many researchers are looking for the causes of asthma. A few alleles have been identified as contributing factors, but none acts in isolation (Akinbami et al., 2010; Bossé & Hudson, 2007). Several aspects of modern life—

257

Some experts suggest a hygiene hypothesis, proposing that “the immune system needs to tangle with microbes when we are young” (Leslie, 2012). Parents are so worried about viruses and bacteria that they overprotect their children, preventing minor infections and diseases that would strengthen their immunity. This hypothesis is supported by data showing that (1) first-

The incidence of asthma increases as nations get richer, as seen dramatically in Brazil and China. Better hygiene is one explanation, but so is increasing urbanization, which correlates with more cars, more pollution, more allergens, and better medical diagnosis (Cruz et al., 2010). One review of the hygiene hypothesis notes that “the picture can be dishearteningly complex” (Couzin-

Prevention of Health ProblemsThe three levels of prevention (discussed in Chapters 5 and 6) apply to every health problem, including the two just reviewed: obesity and asthma.

Primary prevention requires changes in the entire society. Better ventilation of schools and homes, less pollution, fewer cockroaches, fewer antibiotics, and more outdoor play would benefit everyone. ParticipACTION’s “Bring Back Play” initiative to promote outdoor play use is an example of primary prevention if it makes everyone more likely to be active.

Secondary prevention decreases illness among high-

Finally, tertiary prevention treats problems after they appear. For asthma, for instance, that means prompt use of injections and inhalers. Even if tertiary prevention does not halt a condition, it can reduce the burden on the child.

258

KEY Points

- Most 6-

to 11- olds are healthy and capable of self- care, with less disease than at any other time of life. - Active play is crucial at this age, for learning as well as for health.

- Unfortunately, obesity and asthma are increasingly common among school-

age children. - Health problems among children are partly genetic, partly familial, and partly the result of laws and values in the society.