8.1 The Nature of the Child

As explained in the previous chapter, steady growth, brain maturation, and intellectual advances make middle childhood a time when children gain independence and autonomy (see At About This Time). They acquire an increasing ability to regulate themselves, to take responsibility, and to exercise self-

One result is that school-

Signs of Psychosocial Maturation over the Years of Middle Childhood

| Children responsibly perform specific chores. |

| Children make decisions about a weekly allowance. |

| Children can tell time, and they have set times for various activities. |

| Children have homework, including some assignments over several days. |

| Children are less often punished physically than when they were younger. |

| Children try to conform to peers in clothes, language, and so on. |

| Children voice preferences about their after- |

| Children are responsible for younger children, pets, and, in some places, work. |

| Children strive for independence from parents. |

Industry and Inferiority

Although adults have always taught 6-

Erikson’s InsightsThe tension between productivity and incompetence is the fourth psychosocial crisis, industry versus inferiority, as described by Erik Erikson. He noted that during these years, the child “must forget past hopes and wishes, while his exuberant imagination is tamed and harnessed to the laws of impersonal things,” and he becomes “ready to apply himself to given skills and tasks” (Erikson, 1963).

Learning to read and add numbers can be a painstaking and boring process. For instance, slowly sounding out “Jane has a dog” or writing “3 + 4 = 7” for the hundredth time is not exciting. Yet children are intrinsically motivated to read a page, finish a worksheet, memorize a spelling word, colour a map, and so on. Similarly, they enjoy collecting, categorizing, and counting whatever they accumulate—

Overall, children judge themselves as either industrious or inferior—deciding whether they are competent or incompetent, productive or useless, winners or losers. Being productive is intrinsically joyous, and it fosters the self-

293

Parents who are supportive of their children’s attempts and initiatives help them master skills and develop a sense of confidence in themselves. In contrast, parents who provide little or no encouragement to their children run the risk of instilling feelings of inferiority and helplessness in them.

A sense of industry may be a defence against early substance use as well. In a longitudinal study in Arizona of 509 Grade 3 and 4 students over a five-

Freud on LatencySigmund Freud described this period as latency, a time when emotional drives are quiet and unconscious sexual conflicts are submerged. Some experts complain that “middle childhood has been neglected at least since Freud relegated these years to the status of an uninteresting ‘latency period’” (Huston & Ripke, 2006).

But in one sense, at least, Freud was correct: Sexual impulses are quiet. Even when children were betrothed before age 12 (rare today, but not uncommon in earlier centuries), the couple had little interaction. Everywhere, boys and girls in middle childhood choose to be with others of their own sex. Indeed, boys who scrawl “Girls stay out!” on their clubhouses and girls who complain that “boys stink” are typical.

Self-Concept

As children mature, they develop their self-

That global self-

As self-

Compared With OthersThe schoolchild’s self-

294

During preadolescence, “the peer group exerts an increasingly salient socializing function” (Thomaes et al., 2010). Research in many nations has found that teaching anxious children to confide in friends as well as to understand their own emotions helps them develop a better self-

Parents, peers, older children, and even strangers become potential critics. Children depend on social comparison, comparing themselves with other people, as they develop their self-

For all children, increasing self-

TAO IMAGES LIMITED/GETTY IMAGES

Culture and Self-

295

Culture seems to be more relevant than objective accomplishment in developing self esteem. For example, Japanese children excel at math on the TIMSS, but only 17 percent are confident of their math ability (Snyder & Dillow, 2010). In Ontario, 33 percent of those taking the TIMSS are confident of their math ability, and those who enjoy math and are confident in their abilities have higher levels of achievement (Mullis et al., 2012a). In contrast, in Estonia low self-

Resilience and Stress

Young children depend on their families for many things, including food, emotional support, learning, and life itself. Then “experiences in middle childhood can sustain, magnify, or reverse the advantages or disadvantages that children acquire in the preschool years” (Huston & Ripke, 2006).

Supportive families continue to be protective, but children may escape destructive family influences by finding their own niche in the larger world. Some children break free, seemingly unscathed by early experiences. They have been called “resilient” or even “invincible.” Resilience has been defined as “a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity” (Luthar et al., 2000). Note the three parts of this definition:

- Resilience is dynamic, not stable: It may be evident at one age but not a later one.

- Resilience is a positive adaptation to stress. For example, if home problems lead a child to greater involvement with schoolwork and school friends, that is positive adaptation.

- Adversity must be significant. Some adversities are comparatively minor (large class size, poor vision) and some are major (victimization, neglect). Children cope with all kinds of adversities, but not all coping is resilient.

Over the past six decades, researchers across the globe have been exploring resilience in children who have faced adversity. In Canada, Michael Ungar and Linda Liebenberg are directors of the Resilience Research Centre at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, where they have been examining children’s responses to different types of stress in various cultures and countries.

In a 2008 review of the resilience literature, Ungar (2008) found that the term had different meanings depending on its context. Specifically, resilience

- describes a group of characteristics that allow certain children to grow up successfully despite being born into difficult circumstances

- refers to a child’s ability to demonstrate competence under stress

- is the ability to recover from traumatic experiences.

In studying 1500 children around the world, Ungar concluded that culture and context are important factors in determining a child’s ability to deal with stress. As an example, he quotes Mani, a young Innu woman from Sheshatshkiu in Newfoundland and Labrador, who made the following comments in response to her cousin’s suicide:

My coping skills were tested and it was hard.…I never knew that kind of devastation existed in my own family members. I didn’t know how to react or respond.

I didn’t know the difference between what was real and wasn’t real. I just couldn’t get myself to speak or think. It was a scary time for us and the scars will live on. We did receive lots of support from community leaders, workers, and members. It was kind of nice how my whole family were together like that… Our family needs to stay together and focused now. I need them to balance their lives and mine.

[Ungar, 2008]

296

Note that Mani received support from her community and family, which was crucial to her resilient response to this crisis. Note too that even with such support and her determination to cope, Mani realizes that “the scars will live on.”

Indeed, current thinking about resilience (see TABLE 8.1), with insights from dynamic-

| 1965 | All children have the same needs for healthy development. |

| 1970 | Some conditions or circumstances— |

| 1975 | All children are not the same. Some children are resilient, coping easily with stressors that cause harm in other children. |

| 1980 | Nothing inevitably causes harm. Both maternal employment and preschool education, once thought to be risks, are often helpful. |

| 1985 | Factors beyond the family, both in the child (low birth weight, prenatal alcohol exposure, aggressive temperament) and in the community (poverty, violence), can be very risky for children. |

| 1990 | Risk- |

| 1995 | No child is invincibly resilient. Risks are always harmful— |

| 2000 | Risk- |

| 2008 | Focus on strengths, not risks. Assets in child (intelligence, personality), family (secure attachment, warmth), community (schools, after- |

| 2010 | Strengths vary by culture and national values. Both universal ideals and local variations must be recognized and respected. |

| 2012 | Genes as well as cultural practices can be either strengths or weaknesses; differential sensitivity means identical stressors can benefit one child and harm another. |

Cumulative StressOne important discovery is that accumulated stresses over time, including minor ones (called “daily hassles”), are more devastating than an isolated major stress. Almost every child can withstand a single stressful, momentary event, but repeated stresses make resilience difficult (Jaffee et al., 2007).

Another example comes from children who survived Hurricane Katrina, in Louisiana. Years after the hurricane, about half were resilient but the other half (especially those in middle childhood) were still traumatized. The incidence of serious psychological problems was affected more by ongoing problems—

An international example of resilience comes from Sri Lanka, where many children have been exposed to war, the 2004 tsunami, poverty, deaths of relatives, and relocation. The accumulated stresses, more than any single problem, increased pathology and decreased achievement. Researchers point to “the importance of multiple contextual, past, and current factors in influencing children’s adaptation” (Catani et al., 2010).

Cognitive CopingCoping measures reduce the impact of repeated stress. One factor is the child’s own interpretation of events. For example, cortisol levels increased in low-

297

In general, a child’s interpretation of a family situation (poverty, divorce, and so on) determines how that context affects him or her (Olson & Dweck, 2008). Some children consider the family they were born into a temporary hardship; they look forward to the day when they can leave childhood behind. Other children experience parentification: They act as parents, taking on the roles and responsibilities that are traditionally associated with adults (Hooper, 2007). When this happens, it can interfere with or halt a child’s own development.

Researchers have noted two distinct types of parentification:

- emotional, in which children try to respond to the emotional demands of their parents and siblings, for example, by being the peacemaker in the family

- practical, in which children do all the household’s daily chores, such as cooking meals, cleaning up, and paying bills.

Emotional parentification almost always has a destructive effect on children’s development. Spending long periods as their parent’s confidante can mean children suppress their own emotional needs, and this can cripple their ability to develop adult relationships (Earley & Cushway, 2002; Jurkovic et al., 2001).

Practical parentification has milder effects on a child’s development. As mentioned in Chapter 1 in the discussion on family systems theory, the actions of one family member always affect the other members. If a child takes on more household responsibilities, this may reduce the parents’ anxieties. Consequently, the child may feel a sense of accomplishment as the parents’ stress levels decrease (Jurkovic & Casey, 2000; Minuchin et al., 1967).

Escaping Family StressesA 40-

One such infant was Michael, born preterm, weighing just over 2 kilograms. His parents were low-

Michael was not the only resilient one. Amazingly, about one-

As was true for many of these children, school and then college can be an escape. An easygoing temperament and a high IQ help children cope with adversity, but they are not essential. For the Hawaiian children, “a realistic goal orientation, persistence, and ‘learned creativity’ enabled…a remarkable degree of personal, social, and occupational success,” even for those with learning disabilities (E. Werner & Smith, 2001).

298

Social Support and Religious FaithSocial support is a major factor that strengthens the ability to deal with stress, especially for minority children who are aware of prejudice against them (Gillen-

When children attempt to seek out experiences that will help them overcome adversity, it is critical that resources, in the form of supportive adults or learning opportunities, be made available to them so that their own self-

[Kim-

A specific example is seen in a study of refugee children in Alberta. Fantino and Colak (2001) recount the story of 11-

In the beginning, Sanela had nightmares so vivid they kept her terrified for days at a time. She refused to talk about the war, her father, or her homeland. It was only after receiving extensive settlement support and counselling and being connected to a Canadian “host friendship” family that Sanela began to show a sense of relief and some signs of optimism about her future.

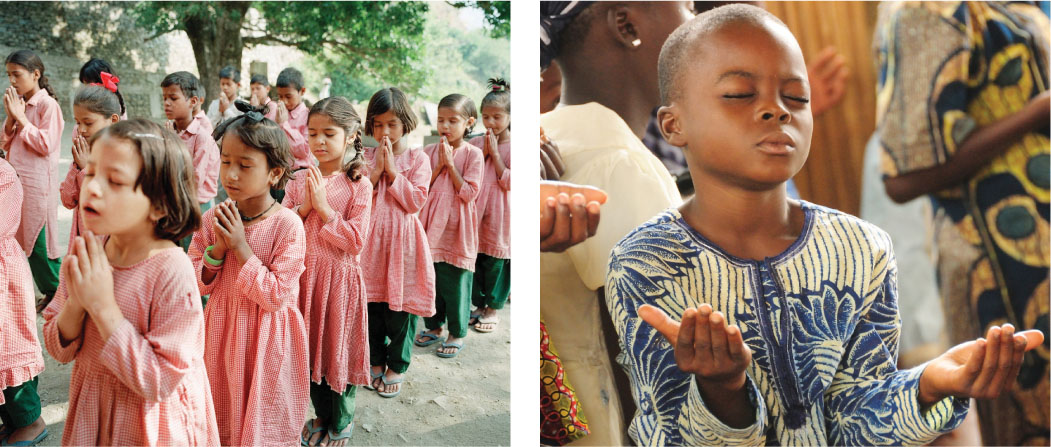

Aside from social support services, children may also make use of religion to bolster their resilience. Religion often provides support via adults from the same faith group (P. E. King & Furrow, 2004). Church involvement particularly helps African-

NAFTALI HILGER/LAIF/REDUX

299

Prayer may also foster resilience. In one study, adults were required to pray for a specific person for several weeks. Their attitude about that person changed (Lambert et al., 2010). Ethics precludes such an experiment with children, but it is known that children often pray, expecting that prayer will make them feel better, especially when they are sad or angry (Bamford & Lagattuta, 2010). As you now know, expectations and interpretations can be powerful.

KEY Points

- In middle childhood, children seek to be industrious, actively mastering various skills.

- Social comparison helps children refine their self-

concept. - Resilient children cope well with major adversities.

- Schools, places of worship, and many other institutions help children deal with difficult family conditions.