8.2 Families and Children

No one doubts that genes affect personality as well as ability, that peers are vital, and that schools and cultures influence what, and how much, children learn, as well as how they feel about themselves. Some researchers have even suggested that genes, peers, and communities have so much influence that parenting has little impact—

As an example, Midgett and his colleagues (2002) examined the relationship between parent–

Shared and Non-shared Environments

Environmental influence on any two children comes either from factors that are shared (both children experience the same environment) or factors that are not shared. For example, all the children raised in one home might be said to share the same parents, and children who grow up in separate nations might have non-

Many studies have found that children are less affected by shared environment than by non-

Even psychopathology (Burt, 2009) and sexual orientation (Långström et al., 2010) arise primarily from genes and non-

300

Since shared environment has little impact, does this mean that parents are merely caretakers, providing basic care (food, shelter) with little influence on children’s personality, intellect, and so on, no matter what rules, routines, or responses they provide? No! Recent findings reassert parental influence. The formula and calculation of shared and non-

For example, if relocation, divorce, unemployment, or a new job occurs in a family, the impact on each child depends on that child’s age, genes, resilience, and gender. Thus, moving to another town might disturb a 9-

The variations just mentioned do not apply equally to all siblings: Differential sensitivity means that one child is more affected, for better or worse, than the other (Pluess & Belsky, 2010). Even if siblings are raised together, the mix of parental personality, genes, age, and gender may lead one child to become antisocial, another to have a personality disorder, and a third to be resilient (Beauchaine et al., 2009).

ESPECIALLY FOR Scientists How would you determine whether parents treat all their children the same way?

Proof is very difficult when human interaction is the subject of investigation, since random assignment is impossible. Ideally, researchers would find identical twins being raised together and would then observe the parents’ behaviour over the years.

In addition to variations within the home, parents choose for their children many outside, non-

Even identical twins, with the same genes, age, and sex, may not share their home or school environment (Caspi et al., 2004). For example, one mother spoke of her monozygotic daughters:

Susan can be very sweet. She loves babies…she can be insecure…she flutters and dances around… There’s not much between her ears… She’s exceptionally vain, more so than Ann. Ann loves any game involving a ball, very sporty, climbs trees, very much a tomboy. One is a serious tomboy and one’s a serious girlie girl. Even when they were babies I always dressed one in blue stuff and one in pink stuff.

[quoted in Caspi et al., 2004]

Even though the mother from the beginning dressed her daughters differently, how the girls reacted, their personalities, their personal preferences, and their activities would then encourage or discourage the environment the mother was creating for them.

Family Structure and Family Function

Family structure refers to the legal and genetic connections among people living in the same household. Family function refers to how a family cares for its members. The data affirm that parents are crucial for family function, determining non-

Part of the answer is known. No matter what the structure, one family function is crucial: People need family love and encouragement. Beyond that, needs vary by age. As you have seen, infants need responsive caregiving, frequent exposure to language, and social interaction; preschoolers need encouragement and guidance. Later chapters of this text describe the needs of adolescents and adults.

301

During middle childhood, children need five things from their families:

- Physical necessities. Although children in middle childhood eat, dress, and go to sleep without help, families furnish food, clothing, and shelter.

- Learning. These are prime learning years: Families choose schools, help with homework, and encourage education.

- Self-

respect . Families give each child a way to shine. Especially if academic success is elusive, opportunities in sports, the arts, and so on are crucial. - Peer relationships. Families foster friendships via play dates, group activities, school choice, and classroom support.

- Harmony and stability. Families provide protective, predictable routines within a home that is a safe haven for everyone.

Now consider the tire-

Continuity and ChangeNo family always functions perfectly, but children worldwide fare better in families than in other institutions (such as group residences), and best if families provide the five functions listed above. Item five, harmony and stability, is especially crucial in middle childhood: Children like continuity, not change; peace, not conflict. To some degree, this is unique to middle childhood. Indeed, a decade or so later, emerging adults enjoy new places, seek challenges, and provoke arguments with friends and family. University students sometimes study in other nations or stay up all night debating issues with friends—

The importance of continuity is evident from the findings of a study from Japan (Tanaka & Nakazawa, 2005). The researchers began with the knowledge that children benefit from living with their fathers. Father absence correlates with poverty and divorce, both also harmful. Given that, the researchers wanted to learn how children would be affected if the father’s absence did not correlate with low income and hostile mother–

An opportunity for such research arose in Japan because many Japanese corporations transfer employees from one location to another to help them understand how the company functions. Some families moved with the father, while others did not. As a result, researchers were able to study two similar groups of children, with only one major difference between the groups: whether the father was present or absent every day.

The hypothesis was that children who moved with their fathers would benefit because his daily presence would help them with self-

302

Military FamiliesNorth American children in military families face particular challenges in terms of the fifth point on the list of family functions, stability. Military parents repeatedly depart and return, and families typically relocate every few years (Riggs & Riggs, 2011; Titus, 2007). Generally, adults are happy when a soldier comes home safely, but even a safe return may disrupt the children’s lives. Military children experience emotional problems and a decrease in achievement with each change (Hall, 2008).

For that reason, since 1991, the Canadian Forces (CF) and the Canadian/Military Family Resource Centres (C/MFRCs) have partnered together to try to deliver responsible services and support to CF families. Currently there are 32 C/MFRCs across Canada, five in the United States, and six more overseas. These centres are designed to provide various educational and support services to meet the unique needs of these families, especially in regard to stressful situations that may arise from a parent’s deployment overseas.

Specifically, such support includes information on issues such as the emotional cycle family members are likely to experience when a parent is deployed; preparing for departure; dealing with the absence; preparing for the return; and creating a new family routine after the return (National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces, 2013).

The same underlying principles apply to non-

Diversity of StructuresWorldwide, two cohort factors—

Two-

Single- One-

More Than Two Adults

|

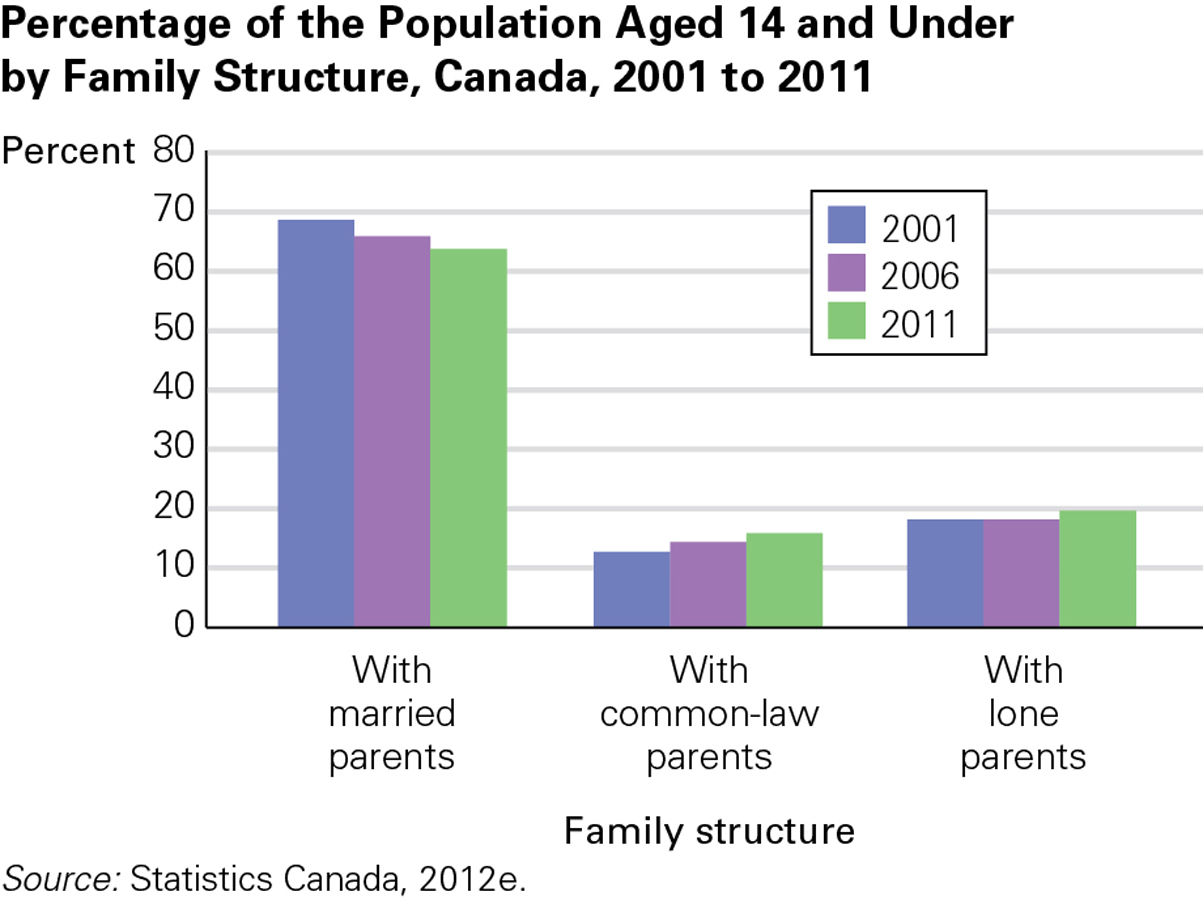

In Canada, about 80 percent of children aged 14 and under live in two-

GREG ELMS/GETTY IMAGES

The number of same-

303

Almost 1 in 5 Canadian children (19 percent) currently live in a single-parent family. By far, most of these children (82 percent) live with a female single parent. Overall, the number of single-

Two-

The distinction between one-

304

Connecting Family Structure and Function

Structure influences but does not determine function. Which structures make it more likely that the five family functions (necessities, learning, self-

Benefits of Nuclear FamiliesIn general, nuclear families function best; children in the nuclear structure tend to achieve higher grades in school and have fewer psychological problems. A scholar who summarized dozens of studies concluded, “Children living with two biological married parents experience better educational, social, cognitive, and behavioural outcomes than do other children” (Brown, 2010). Does this mean that parents should all marry and stay married? Developmentalists are not that prescriptive because some of the benefits are correlates, not causes.

Many advantages of nuclear families begin before the wedding because education, earning potential, and emotional maturity all make it more likely that people will marry, have children, and stay married. Thus, brides and grooms bring personal assets to their new family. In other words, there is a correlation between child success and married parents partly because of who marries, not because of the fact of marriage itself.

To some extent, however, marriage in itself does benefit children. The selection effects noted earlier are not the entire story (Amato, 2005; Brown, 2010). Ideally, mutual affection between spouses encourages them to become wealthier and healthier than either would be alone, and that helps their children. Furthermore, the parental alliance, in which the mother and father support each other in their commitment to the child, decreases neglect and abuse and increases the likelihood that children have someone to read to them, check homework, invite friends over, buy new clothes, and save for their future.

In fact, a broad survey of parental contributions to college and university tuition found that the highest contributions came from nuclear families. These results might be expected when two-

Function of Other Two-

Same-

The step-

305

Income and intimacy aside, another disadvantage of step-

Harmony may also be absent, especially if the child’s loyalty to both biological parents is undermined by ongoing disputes between them. A solid parental alliance is more difficult to form when it includes three adults—

Another version of a two-

Adequate health care and schooling for children is particularly difficult in skipped-

Finally, adoptive families typically function well for children, although they can vary tremendously in their ability to meet the needs of children. Many of the children in such families pose special challenges, particularly at puberty and later. Support from agencies and communities is needed, but not always available.

Single-

Family and community support for single parents make a difference. Some support programs help single parents access education, legal assistance, or financial counselling, which can help with their overall well-

ESPECIALLY FOR Single Parents You have heard that children raised in one-

Do not get married mainly to provide a second parent for your child. If you were to do so, things would probably get worse rather than better. Do make an effort to have friends of both sexes with whom your child can interact.

On the other hand, millions of children raised by single parents are well loved and nurtured. It is important to keep in mind that single parents are a diverse group, and most are not depressed or in poor health. Remember that difference is not always deficit; good caregiving is more difficult in the single parent structure, but it is far from impossible.

306

Culture and Family StructureCultural variations in the support provided for various family structures make it hard to conclude that a particular structure is always best. For example, many French parents are unmarried. Some might assume that an unmarried mother is also a single mother. However, French unmarried mothers generally live with their children’s fathers. French cohabiting parents separate less often than do married parents in North America, which suggests more stability in the average French cohabiting family than in the average married structure in North America. An analysis of 27 countries found that for women in particular, social context had a major impact on their happiness (Lee & Ono, 2012), which probably would affect their ability to parent successfully.

For children in North America, the cohabiting structure is more challenging than marriage because cohabiting parents separate more often than married parents do (Musick & Bumpass, 2012). This is one example of a general truth: Function is affected by national mores (S. L. Brown, 2004; Gibson-

Ethnic norms matter as well. Single parenthood is more accepted among African-

Another family structure that has emerged in Canada and some other countries is that of the astronaut family in which family members live in different and often widely separated countries across the globe. A common example of astronaut families consists of Chinese parents (from Hong Kong, Taiwan, or mainland China) and their children (known as satellite or parachute children) who have emigrated from their home country for the sake of economic or educational opportunities abroad. At some point, the father or mother or both return to the home country to pursue their careers (Man, 1994, 2013).

For example, a couple with two children may leave Hong Kong for Vancouver, where the parents work for several years before the father (the “astronaut”) returns to Hong Kong to establish a business there. If the mother and father both return, the children may be left with grandparents in Vancouver, or, if they are old enough, they may be left on their own while they finish university and begin their careers. Typically, parents will travel frequently between their home and adopted countries to maintain family ties.

Astronaut families differ from single-

In discussing various and different family structures, it is important not to conclude that one is better than another. Contrary to the averages, thousands of nuclear families are dysfunctional, thousands of step-

307

Family Challenges

Two factors interfere with family function in every structure, ethnic group, and nation: low income and high conflict. Many families experience both poverty and acrimony because financial stress increases conflict and vice versa (McLanahan, 2009).

PovertySuppose a 6-

What if the 6-

Family income correlates with structure. Many low-

Family function is also affected by income: Obviously money is needed for the first of the five functions listed earlier—

The effects of poverty on children are cumulative; most children are resilient if income drops for a year, but an entire childhood in poverty is difficult to overcome. Low SES may be especially damaging during middle childhood (Duncan et al., 2010). Several researchers have developed the family-

Reaction to wealth may also be harmful. Children in high-

Some intervention programs aim to teach parents to be more encouraging and patient (McLoyd et al., 2006). In low-

Remember the dynamic-

If that is so, more income might improve family functioning. Some support for this idea comes from research indicating that children in single-

308

These findings are suggestive, but controversial and value-

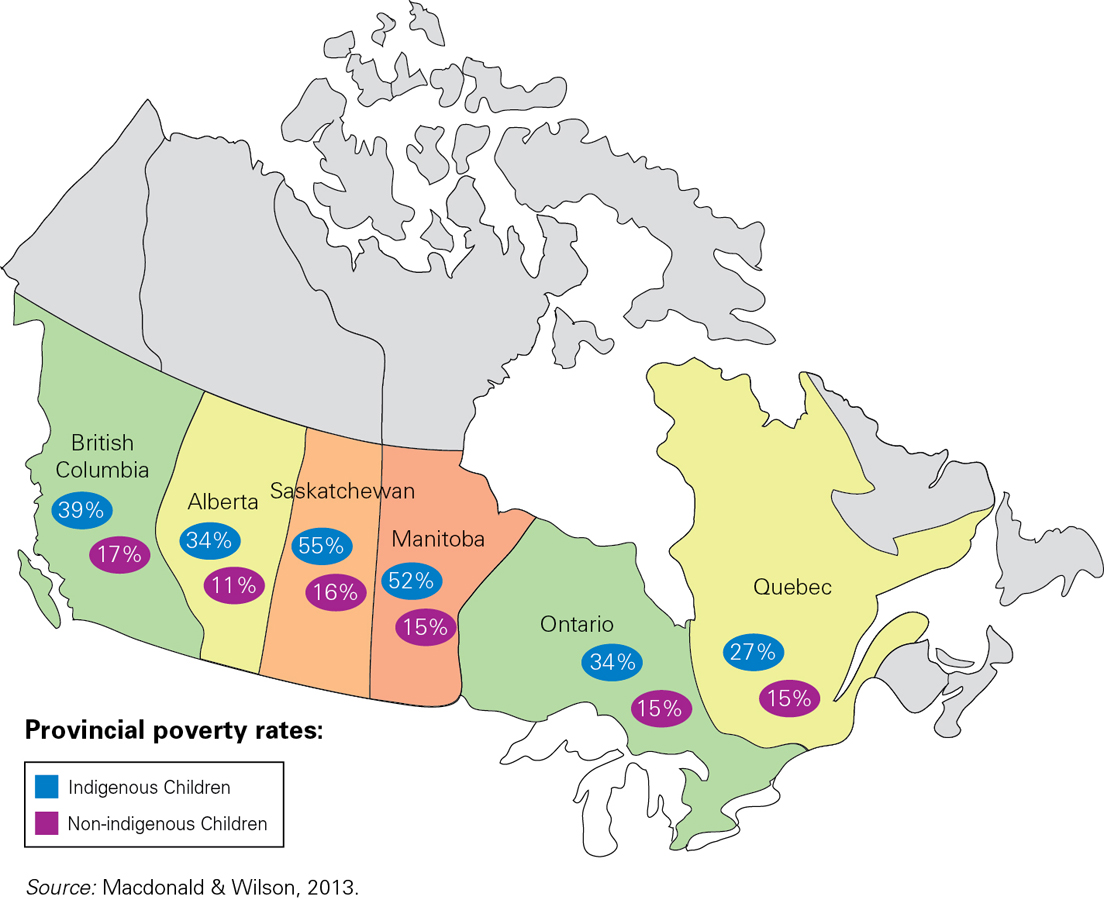

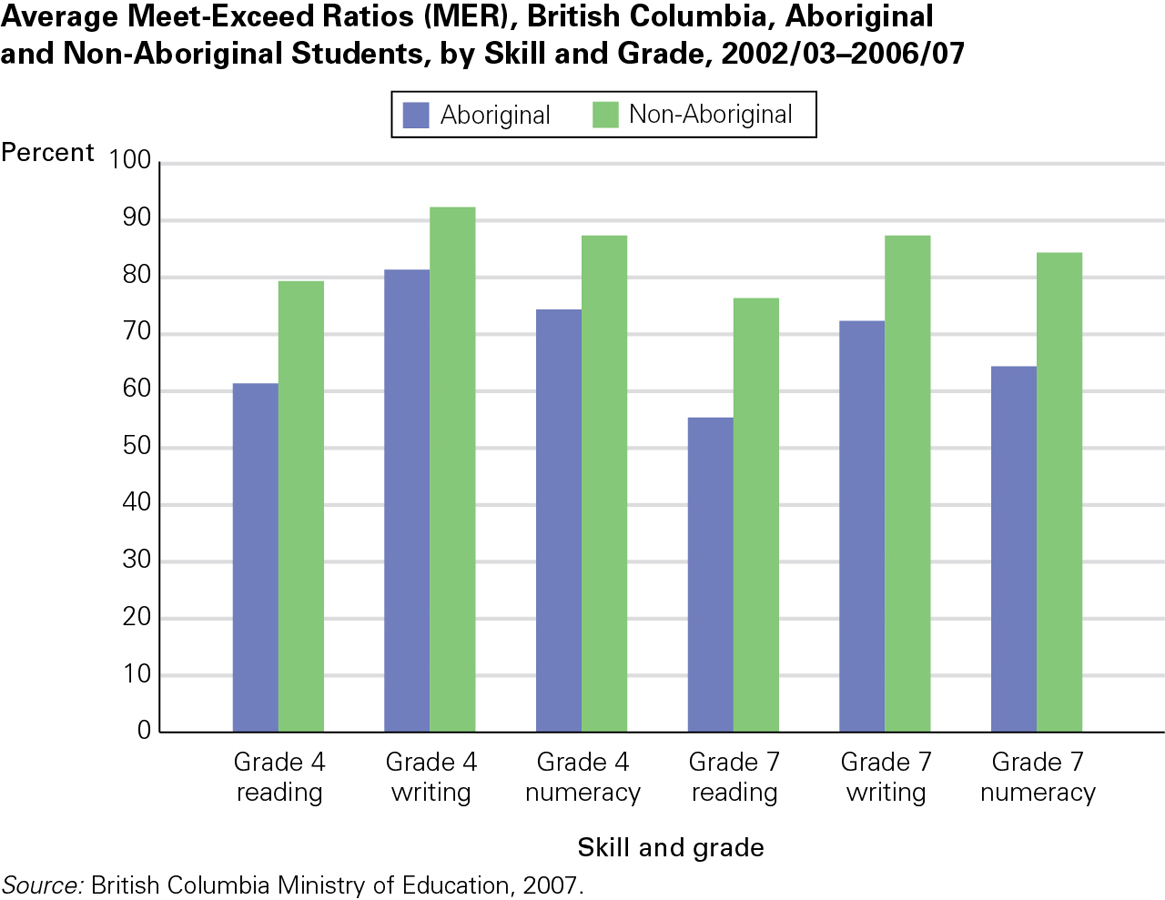

As you read in Chapter 7, many experts have called for closing the “education gap” that exists between Aboriginals and non-

A Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) report makes a number of recommendations for eliminating poverty among Aboriginal children, some of which involve increasing government funding for various programs. For example, the report suggests that if the government increased Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada’s budget by 11 percent, the worst child poverty among status First Nations children could be completely eliminated (Macdonald & Wilson, 2013). This is a worthy goal, the price does not seem prohibitive, and as noted in Chapter 7, some experts believe that doing so could boost the Canadian economy by about $170 billion over the next 15 years (Sharpe & Arsenault, 2010). The question remains whether the political willpower and popular support exist to achieve such a goal.

309

OBSERVATION QUIZ

What do you think are some of the reasons for the Aboriginal education gap?

There are many complex reasons, including poverty, unstable living conditions, feelings of isolation, lack of funds for books and equipment, racism, and mistrust of educational institutions.

ConflictThere is no controversy about conflict. Every researcher agrees that family conflict harms children, especially when adults fight about child-

The impact of genes on children’s reactions to conflict was explored in a longitudinal study of family conflict in 1734 married parents, each with a twin who was also a parent and part of the research. The twins’ husbands or wives, and an adolescent from each family, were also studied. Genetics as well as conflict could be analyzed, since 388 of the pairs of twins were monozygotic and 479 were dizygotic. Each adolescent was compared with a cousin, who had half (if the parent was monozygotic) or a quarter (if the parent was dizygotic) of the same genes (Schermerhorn et al., 2011).

Participants consisted of 5202 individuals, one-

The researchers found that although genes had some effect, conflict itself was the main influence on the child’s well-

Simple disagreement (assessed by both members of each couple) did not do much harm to the child—

Even though conflict had a greater impact than genes, one measure did show genetic influence—

310

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Divorce for the Sake of the Children

Opposing perspectives on divorce begin with three facts:

- About 40 percent of Canadian marriages end in divorce. The divorce and remarriage rate in the United States is even higher: Almost half of all marriages end in divorce.

- On average, children fare best, emotionally and academically, with married parents.

- Divorce tends to impair children’s academic achievement and psychosocial development for years, even decades.

A simple conclusion from these three facts might be that every couple should marry before they have children, and that no married couple should divorce. That is the perspective taken by many adults. But the opposite side—

Opinions are strongly influenced by each person’s past history and cultural values. For example, married parents who stay together are much more negative about divorce than are divorced adults. Adults whose parents divorced tend to have a much more positive take on divorce than adults whose parents stayed together (Moon, 2011).

Some argue that attitudes toward marriage account for the problem of high divorce rates (Cherlin, 2009). North American culture idealizes both marriage and personal freedom. As a result, many young adults assert their independence by marrying “for love.” Then, when they are overwhelmed by child care and financial stress, romance fades, the marriage becomes strained, and they divorce.

Often the happiest time is right after the wedding, before children are born; the least happy time is when the children are infants or young teenagers. Marriage happiness dips during children’s infancy and rises when the children are self-

Because marriage remains the ideal, divorced adults often blame their former mate or their own poor decision for the breakup. They may then enter into a second marriage—

Scholars now describe marriage and divorce as a process, with transitions and conflicts before and after the formal events (Magnuson & Berger, 2009; Potter, 2010). As you remember, resilience is difficult when a child must contend with repeated changes and ongoing hassles. All couples experience some disagreement and conflict, which are not harmful if the conflict is resolved in a healthy way. How parents deal with conflict is critical in the relationship as well as to the well-

Children’s emotional reactions and coping behaviours are also impacted by the emotionality of their parents’ conflicts (e.g., positive emotions, anger, sadness, fear) (Cummings et al., 2002). Coping is particularly hard when children are at a developmental transition, such as entering Grade 1 or beginning puberty, and when their parents involve them in the conflict.

Looking internationally, it is noteworthy that divorce is rare in some nations, especially in the Middle East and Africa. In those regions, adults expect marriages to endure, so in-

Given all of this, young adults may avoid marriage to avoid divorce. This strategy is working—

On the one hand, marriages need not be satisfying to the parents in order to function well for the children—

Can any conclusion be drawn by developmental study as to whether divorce is good for the children? As with many other issues, the answer depends on careful analysis, case by case.

311

KEY Points

- Parents influence their children’s development primarily in non-

shared ways that differ for each child. - During middle childhood, families ideally provide basic necessities and foster learning opportunities, self-

respect, friendships, harmony, and stability. - Every family structure can support child development, but children from nuclear families, on average, are most likely to develop well.

- Family poverty and conflict are usually harmful to 6-

to 11- year- olds, although genes and culture can provide some protection. - When parents are stressed by poverty, divorce, or anything else, they are less likely to nurture children well.