8.4 Children’s Moral Values

Although the origins of morality are debatable (see Chapter 6), researchers have found significant evidence showing that even very young children understand moral issues, that is, the difference between right and wrong. Ages 7 to 11 are

years of eager, lively searching on the part of children…as they try to understand things, to figure them out, but also to weigh the rights and wrongs.…This is the time for growth of the moral imagination, fueled constantly by the willingness, the eagerness of children to put themselves in the shoes of others.

[Coles, 1997]

317

This optimistic assessment seems validated by detailed research. In middle childhood, children are quite capable of making moral judgments, differentiating universal principles from mere conventional norms (Turiel, 2008a). Empirical studies show that throughout middle childhood, children readily suggest moral arguments to distinguish right from wrong (Killen, 2007).

Many forces drive children’s growing interest in such issues. Three of them are (1) peer culture, (2) personal experience, and (3) empathy. As already explained, part of the culture of children involves moral values, such as being loyal to friends and protecting children from adults. A child’s personal experiences also matter. For example, children in multi-

Empathy becomes stronger in middle childhood because children are more aware of one another. This increasing perception can backfire, however. One example was just described: Bullies become adept at picking victims who are rejected by classmates, and then others admire the bullies (Veenstra et al., 2010). However, the increase in empathy during middle childhood at least allows the possibility of moral judgment that notices, and defends, children who are unfairly rejected.

Obviously, ethical advances are not automatic. Children who are slow to develop theory of mind—

Moral Reasoning

Much of the developmental research on children’s moral thinking began with Piaget’s descriptions of the rules used by children as they play (Piaget, 1932/1997). This led to Lawrence Kohlberg’s description of cognitive stages of morality (Kohlberg, 1963).

Kohlberg’s Levels of Moral ThoughtKohlberg described three levels of moral reasoning and two stages at each level (see TABLE 8.3), with parallels to Piaget’s stages of cognition (see also TABLE 1.5).

- Preconventional moral reasoning is similar to preoperational thought in that it is egocentric; children seek pleasure and avoid pain rather than focusing on social concerns.

- Conventional moral reasoning parallels concrete operational thought in that it relates to specific practices: Children try to follow societal norms, that is, what parents, teachers, and friends do.

- Postconventional moral reasoning uses formal operational thought; people use logic in developing a personal moral code, questioning “what is” in order to decide “what should be.”

| Level I: Preconventional Moral Reasoning The goal is to get rewards and avoid punishments; this is a self-

Level II: Conventional Moral Reasoning Emphasis is placed on social rules; this is a parent-

Level III: Postconventional Moral Reasoning Emphasis is placed on moral principles; this level is centred on ideals.

|

According to Kohlberg, cognition advances morality. During early and middle childhood, children’s answers shift from being preconventional to conventional: Concrete thought and peer experiences help children move past the first two stages (level I) to the next two stages (level II). Postconventional reasoning does not appear until later, if at all.

Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to school-

318

Heinz went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said “no.” The husband got desperate and broke into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife. Should the husband have done that? Why?

[Kohlberg, 1963]

Kohlberg judged moral development not by answers, but by the reasons for the answers. Thus, the why is crucial. For instance, someone might say that the husband should steal the drug because he needs his wife to care for him (preconventional), or because people will blame him if he lets his wife die (conventional), or because human life is more important than obeying the law (postconventional).

Criticisms of KohlbergKohlberg has been criticized for not appreciating cultural or gender differences or the cognitive advancement of young children from early on. He valued abstract justice more than family or cultural loyalty: Not every culture agrees (Sherblom, 2008). Furthermore, his original participants were all boys, which has led to criticisms of gender bias (e.g., Gilligan, 1982).

Some developmentalists maintain that children are actually capable of postconventional moral reasoning at much younger ages than Kohlberg believed. This argument was made most notably by Turiel, who worked with Kohlberg for several years, first as a graduate student at Yale University in 1960 and later as a professor at Harvard. In his own research, Turiel tried to show empirically when young people pass from conventional (stage 4) to postconventional (stage 5) moral reasoning. He found that they actually make this transition while still in early childhood, not in adolescence, as Kohlberg had thought. This discovery led Turiel to formulate the social domain theory, discussed in Chapter 6 (Chuang, private communication, 2013).

319

Turiel argued that even children as young as 2 or 3 years of age can distinguish between different kinds of moral transgressions because of the experiences they have either as direct participants or witnesses. As children interact with their social environment, they interpret and make meaning of these experiences. They can see that not all transgressions are of the same kind. Transgressions that involve issues ofjustice, rights, and welfare (morality) are obviously different from those that are based in the social order (social conventions). For instance, stealing another child’s chocolate bar (a moral transgression) is quite a different matter from wearing pyjamas to school (which violates a social convention).

Many other researchers have conducted experiments that seem to substantiate Turiel’s theory. For example, Judi Smetana (1981) asked 2-

In one respect, however, Kohlberg was undeniably correct: Children use their intellectual abilities to justify their moral actions. The role of cognition was evident when trios of 8-

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Developing Moral Values

Many adults wonder how best to instill moral values in children. The first thought is to punish immoral behaviour, the authoritarian approach explained in Chapter 6. However, that stops overt behaviour but not covert actions. Ideally children should internalize standards, doing the right thing even when being caught is unlikely.

As noted above, Turiel believed that even very young children can understand the difference between right and wrong and distinguish among transgressions that violate a moral code, those that violate social conventions, and those that violate a personal standard. By middle childhood, children should be using their cognitive advances to develop their own moral code. In other words, they should avoid stealing because they believe it is wrong, not because they are afraid of being punished if caught. How do they learn that?

Parents and other adults sometimes lecture children, sometimes hope children will follow the adult’s example, and sometimes discuss issues, expressing opinions but also listening to their children. What works? A detailed examination of the effect of conversation on morality began with an update on one of Piaget’s moral issues: whether retribution (hurting the transgressor) or restitution (restoring what was lost) is best when someone does something wrong. Piaget believed that restitution was the more advanced punishment; he also found that between ages 8 and 10, children progress from retribution to restitution (Piaget, 1932/1937).

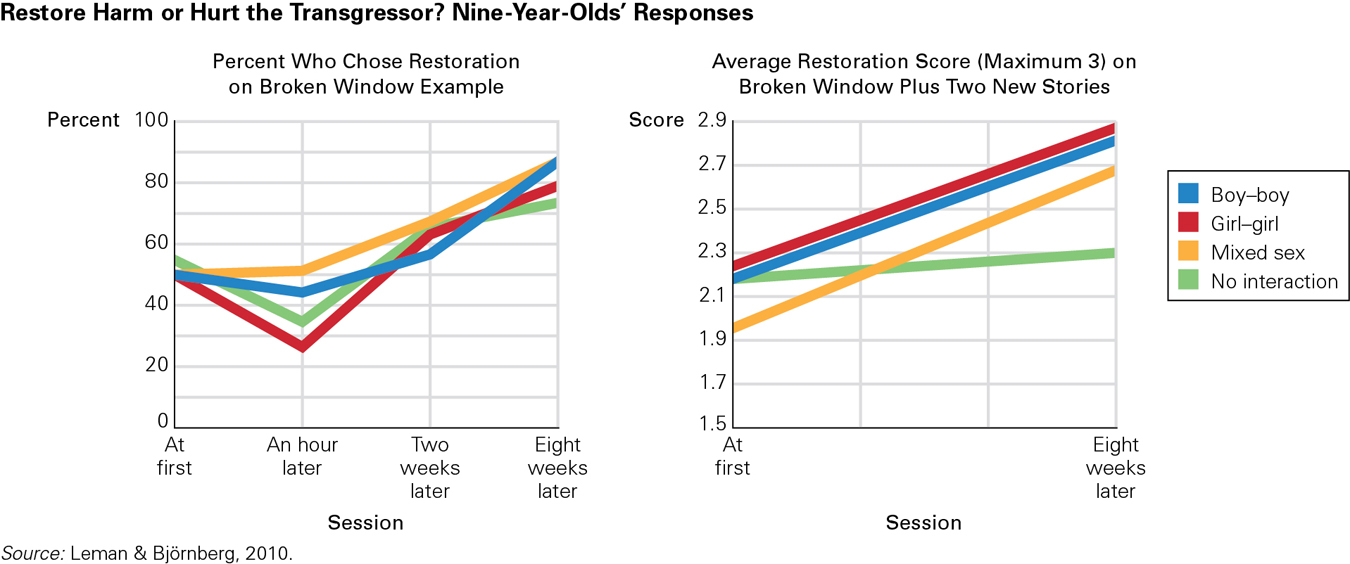

Following Piaget’s hypothesis, researchers asked 133 9-

Late one afternoon there was a boy who was playing with a ball on his own in the garden. His dad saw him playing with it and asked him not to play with it so near the house because it might break a window. The boy didn’t really listen to his dad, and carried on playing near the house. Then suddenly, the ball bounced up high and broke the window in the boy’s room. His dad heard the noise and came to see what had happened. The father wonders what would be the fairest way to punish the boy. He thinks of two punishments. The first is to say: “Now, you didn’t do as I asked. You will have to pay for the window to be mended, and I am going to take the money from your pocket money.” The second is to say: “Now, you didn’t do as I asked. As a punishment you have to go to your room and stay there for the rest of the evening.” Which of these punishments do you think is the fairest?

[Leman & Björnberg, 2010]

The 9-

320

The conversations typically took only five minutes, and the retribution side was more often chosen—

The main conclusion from this study was that children’s “conversation on a topic may stimulate a process of individual reflection that triggers developmental advances” (Leman & Björnberg, 2010). Raising moral issues, and letting children talk about them, may advance their understanding of morality.

What Children Value

Many lines of research have shown that children begin to develop their own morality early on, guided by peers, parents, and culture (Turiel, 2006). Some prosocial values are evident in early childhood. Among these are caring for close family members, cooperating with other children, and not hurting anyone intentionally (Eisenberg et al., 2006).

As children become more aware of themselves and others in middle childhood, they realize that one person’s values may conflict with another’s. Concrete operational cognition, which gives children the ability to use logic about what they see, propels them to think and act ethically (Turiel, 2006), and to recognize immorality in their peers (Abrams et al., 2008) and, later, in their parents, themselves, and their culture. During middle childhood, morality can be scaffolded just as cognitive skills are, with mentors—

321

As children learn to make moral distinctions, another domain of knowledge develops, the psychological or personal domain (see Chapter 6). This domain involves preferences and choices that are purely personal, such as what to eat or wear, and that children tend to think should be outside the jurisdiction of adult authority (Smetana, 2002). Issues of personal freedom often spark intergenerational conflicts between children and parents. Choices that seem strictly personal to children may strike their parents more as involving issues of safety or social conventions. For instance, in Canada, parents may want their 10-

In a study on Taiwanese-

The moral lesson of this chapter, then, is that the psychosocial development of children must be carefully assessed, child by child. As you have seen, self-

KEY Points

- During middle childhood, children are intensely concerned about moral issues.

- Kohlberg believed that cognition and morality advance together, as children gradually become less self-

centred and more concerned about universal principles. - Children learn from the morality and customs of their peers and may choose loyalty to friends over cultural or familial values.

- Ongoing conversation and discussion seems to be the best way for children to internalize a moral perspective.