9.1 Puberty

Puberty refers to the years of rapid physical growth and sexual maturation that end childhood, producing a person of adult size, shape, and sexuality. The forces of puberty are released by a cascade of hormones that produce external growth and internal changes, including heightened emotions and sexual desires.

This process normally starts between ages 8 and 14 and follows the sequence outlined in At About This Time. Most physical growth and maturation end about four years after the first signs appear, although some individuals add height, weight, and muscle until age 20 or so.

For girls, the observable changes of puberty usually begin with nipple growth. Soon a few pubic hairs are visible, then peak growth spurt, widening of the hips, the first menstrual period (menarche), full pubic-

For boys, the usual sequence is growth of the testes, initial pubic-

Unseen Beginnings

Just described are the visible changes of puberty, but the entire process begins with an invisible event: a marked hormonal increase. Throughout adolescence, hormone levels correlate with physiological changes and self-

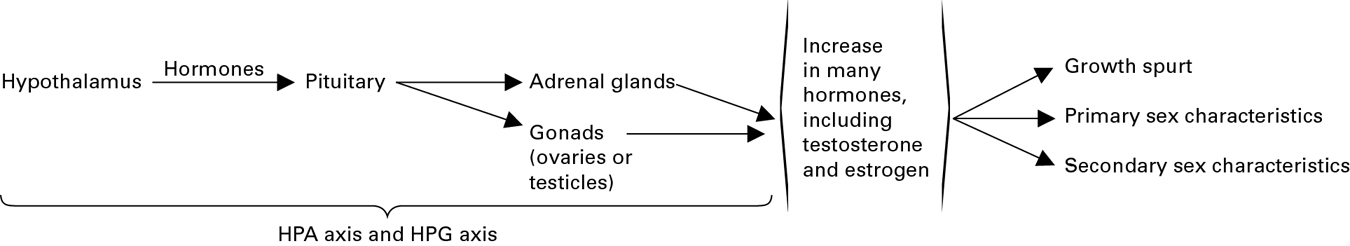

Hormones are body chemicals that regulate hunger, sleep, moods, stress, sexual desire, immunity, reproduction, and many other bodily reactions, including puberty. The process begins deep within the brain when biochemical signals from the hypothalamus signal another brain structure, the pituitary.

329

The Sequence of Puberty

| Girls | Approximate Average Age* | Boys |

|---|---|---|

| Ovaries increase production of estrogen and progesterone** | 9 | |

| Uterus and vagina begin to grow larger | 9½ | Testes increase production of testosterone** |

| Breast “bud” stage | 10 | Testes and scrotum grow larger |

| Pubic hair begins to appear; weight spurt begins | 11 | |

| Peak height spurt | 11½ | Pubic hair begins to appear |

| Peak muscle and organ growth; hips become noticeably wider | 12 | Penis growth begins |

| Menarche (first menstrual period) | 12½ | Spermarche (first ejaculation); weight spurt begins |

| First ovulation | 13 | Peak height spurt |

| Voice lowers | 14 | Peak muscle and organ growth; shoulders become noticeably broader |

| Final pubic- |

15 | Voice lowers; visible facial hair |

| Full breast growth | 16 | |

| 18 | Final pubic- |

|

| *Average ages are rough approximations, with many perfectly normal, healthy adolescents as much as three years ahead of or behind these ages. **Estrogens and testosterone influence sexual characteristics, including reproduction. Charted here are the increases produced by the gonads (sex glands). The ovaries produce estrogens and the testes produce androgens, especially testosterone. Adrenal glands produce some of both kinds of hormones (not shown). |

||

The pituitary produces hormones that stimulate the adrenal glands, located above the kidneys, which produce more hormones. Many hormones that regulate puberty follow this route, known as the HPA (hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal) axis (see Figure 9.1).

The HPG (hypothalamus-pituitary-gonad) axis is another hormonal sequence. In adolescence, gonadotropin-

These sex hormones affect the body’s shape and function, producing additional hormones that regulate stress and immunity (E. A. Young et al., 2008). Estrogens (including estradiol) are female hormones, and androgens (including testosterone) are male hormones, although the adrenal glands produce both hormones in both sexes.

A dramatic increase in estrogens or androgens at puberty produces mature ova or sperm, released in menarche or spermarche. This same hormonal rush awakens interest in sex and makes reproduction biologically possible, although peak fertility occurs four to six years later.

330

Hormonal increases affect psychopathology in sex-

Sexual Maturation

The body characteristics that are directly involved in conception and pregnancy are called primary sex characteristics. During puberty, every primary sex organ (the ovaries, the uterus, the penis, and the testes) increases dramatically in size and matures in function. By the end of the process, reproduction is possible.

At the same time as maturation of the primary sex characteristics, secondary sex characteristics develop. Secondary sex characteristics are bodily features that do not directly affect fertility (hence they are secondary) but that visually signify masculinity or femininity. One secondary characteristic is shape. At puberty, males widen at the shoulders and grow about 13 centimetres taller than females, whereas girls develop breasts and a wider pelvis. Breasts and broad hips are often considered signs of womanhood, but neither is required for conception; thus, they are secondary, not primary, sex characteristics.

Age and Puberty

Parents often have a very practical concern: When will adolescence begin? Some fear precocious puberty (sexual development before age 8) or very late puberty (after age 16), but both are rare (Cesario & Hughes, 2007). Quite normal are increased hormones at any time from ages 8 to 14, with the precise age affected by genes, gender, body fat, and stress.

Genes and GenderAbout two-

Research in the United States indicates that African-

331

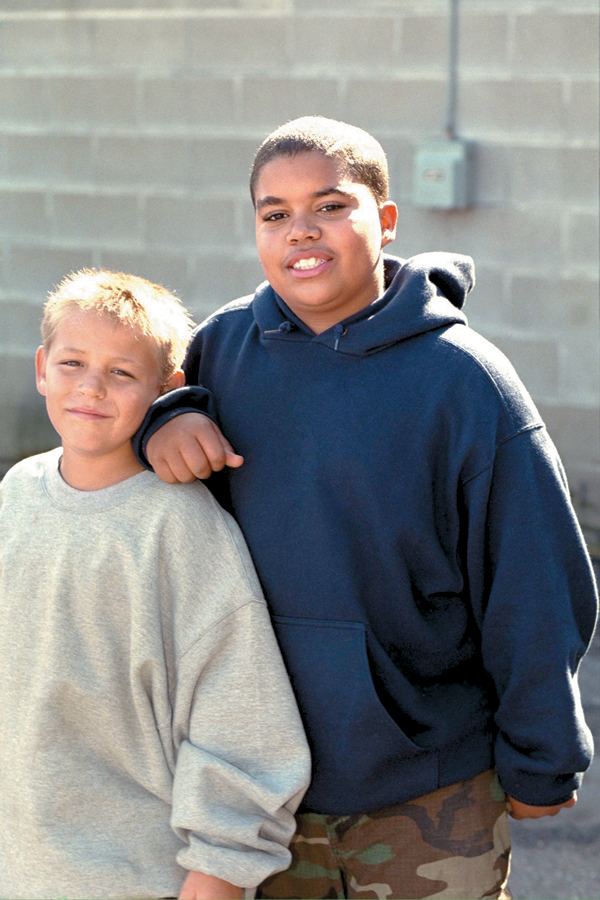

Genes on the sex chromosomes have a marked effect. In height, the average girl is about two years ahead of the average boy. However, the female height spurt occurs before menarche, whereas for boys the increase in height is relatively late, occurring after spermarche (Hughes & Gore, 2007). Thus, when it comes to hormonal and sexual changes, girls are only a few months ahead of boys.

Body FatAnother major influence on the onset of puberty is body fat, at least in girls. Heavy girls reach menarche years earlier than malnourished ones do. Most girls must weigh at least 45 kilograms before they experience their first period (Berkey et al., 2000).

Worldwide, urban children are more often overfed and underexercised compared with rural children. That is probably why puberty starts earlier in the cities of India and China than it does in more remote villages, a year earlier in Warsaw than in rural Poland, and earlier in Athens than in other parts of Greece (Malina et al., 2004).

Body fat also explains why youth reach puberty at age 15 or later in some parts of Africa, although their genetic relatives in North America mature much earlier. Similarly, malnutrition may explain why puberty began at about age 17 in sixteenth-

One hormone causes increased body fat and then triggers puberty: leptin, which stimulates the appetite. Leptin levels in the blood show a natural increase over childhood, peaking at puberty (Rutters et al., 2008). Curiously, leptin affects appetite in females more than it does in males (Geary & Lovejoy, 2008), and body fat is more closely connected to the onset of puberty in girls than in boys. In fact, the well-

Too Early, Too Late

Few adolescents care about speculation regarding hormones or evolution. Only one aspect of pubertal timing matters to them: their friends’ schedules. No one wants to be first or last; every adolescent wants to hit puberty “on time.” Research finds that a wise hope since, for both sexes, early and late puberty increase the rate of almost every adolescent problem.

GirlsThink about the early-

Delayed puberty in girls can be hereditary, but it can also be due to malnutrition, chromosomal abnormalities, genetic disorders, or illness. If puberty is delayed, girls may become distressed by the differences in their bodies compared to others.

BoysThere was a time when early-

332

For the past few decades, early-

ESPECIALLY FOR Parents Worried About Early Puberty Suppose your cousin’s 9-

Probably not. If she is overweight, her diet should change, but the hormone hypothesis is speculative. Genes are the main factor; she shares only one-eighth of her genes with her cousin.

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Stress and Puberty

Stress affects the sexual reproductive system by hastening (not delaying) the hormonal onset of puberty and by making reproduction more difficult in adulthood. Thus puberty arrives earlier if a child experiences, for instance, problems at school, social challenges, low SES, or family instability, such as divorce.

The connection between stress and puberty is provocative. Is stress really a cause of earlier puberty? Perhaps it is only a correlate, and a third variable is the underlying reason why children under stress experience earlier puberty.

A logical third variable would be genes. For instance, mothers who are genetically programmed for early menarche may also be more likely to have early sex. That would make them vulnerable to teenage pregnancy, and if they marry while they are immature, the marriages would likely be turbulent. The fact that their children experience early puberty would then be the result not of the conflicted marriage, but of genes, inherited from their mother.

However, although genes affect age of puberty, careful research finds that stress is in fact a cause, not merely a correlate, of early menarche. It seems that stress hormones, particularly cortisol, directly cause early puberty. For example, in one research study, a group of sexually abused girls began puberty 7 months earlier, on average, than did a matched comparison group. The stress and trauma that the girls faced in their earlier years influenced the timing of puberty (Trickett et al., 2011).

One longitudinal study followed 756 children from infancy to adolescence. Those who were harshly treated (rarely hugged and often spanked) in childhood also had earlier puberty. This study also found that harsh parenting correlated with earlier puberty for daughters, not sons—

A follow-

So why is stress a cause of early puberty? One explanation comes from evolutionary theory:

Maturing quickly and breeding promiscuously would enhance reproductive fitness more than would delaying development, mating cautiously, and investing heavily in parenting. The latter strategy, in contrast, would make biological sense, for virtually the same reproductive-

[Belsky et al., 2010]

This evolutionary explanation seems in accord with the existing evidence (Ellis et al., 2011). In stressful times in the past, for species survival, stressed adolescents needed to replace themselves before they died. Of course, natural selection would postpone puberty during extreme famine (so that pregnant girls or their newborns would not die of malnutrition).

However, natural selection would favour genes that hastened puberty for well-

Today this evolutionary explanation no longer applies. However, the genome has been shaped over millennia; change takes centuries.

333

Growing Bigger and Stronger

For every child, puberty begins a growth spurt—an uneven jump in the size of almost every body part. Growth proceeds from the extremities to the core (the opposite of the earlier proximodistal growth). Thus, fingers and toes lengthen before hands and feet, hands and feet before arms and legs, arms and legs before the torso. Many pubescent children are temporarily big-

Sequence: Weight, Height, and MusclesAs the bones lengthen and harden (visible on X-

A height spurt follows the weight spurt. Then, a year or two later, a muscle spurt occurs. Thus, the pudginess and clumsiness of early puberty are usually gone by late adolescence.

Lungs triple in weight; consequently, adolescents breathe more deeply and slowly. The heart doubles in size as the heart beat slows, decreasing the pulse rate while increasing blood pressure (Malina et al., 2004). Red blood cells increase in both sexes, but dramatically more so in boys, which aids oxygen transport during intense exercise. Endurance improves: Some teenagers can run for long distances or dance for hours.

Both weight and height increase before muscles and internal organs: Athletic training and weight lifting should be tailored to an adolescent’s size the previous year to protect immature muscles and organs. Sports injuries are the most common school accidents. Injuries increase at puberty, partly because the height spurt precedes increases in bone mass, making young adolescents particularly vulnerable to fractures (Mathison & Agrawal, 2010).

Only one organ system, the lymphoid system (which includes the tonsils and adenoids), decreases in size, so teenagers are less susceptible to respiratory ailments. Consequently, mild asthma often disappears at puberty (Busse & Lemanske, 2005), and teenagers have fewer colds than younger children do. This is aided by growth of the larynx, which gives deeper voices to both sexes, dramatically noticeable in boys.

Skin and HairBecause of the increased hormones, the fatty acid composition of perspiration changes into more “adult” body odour. Secretion of oils from the skin also increases, which results in a greater susceptibility to acne.

Hair also changes. During puberty, hair on the head and limbs becomes coarser and darker. New hair grows under arms, on faces, and over sex organs. For males, visible facial and chest hair is sometimes considered a sign of manliness, although hairiness in either sex depends on genes as well as on hormones.

To become more attractive, many teenagers spend considerable time, money, and thought on their head hair—

334

Body Rhythms

The brain of every living creature responds to the environment with natural rhythms that rise and fall by the hours, days, and seasons. Some biorhythms are on a day-

ESPECIALLY FOR Parents of Teenagers Why would parents blame adolescent moods on hormones?

Hormones disrupt adolescents’ circadian rhythms, which in turn can lead to sleep deprivation and mood swings.

The hypothalamus and the pituitary regulate the hormones that affect biorhythms of stress, appetite, sleep, and so on. Hormones of the HPA axis at puberty cause a phase delay in sleep–

Biology (circadian rhythms) and culture (socializing with friends and technology) work in opposite directions, making teenagers increasingly sleep-

Research indicates that 25 percent of Canadians are sleep-

KEY Points

- Hormones begin the sequence of biological changes known as puberty, affecting every body function, including appetite, sleep, and reproductive potential.

- Although many similarities are evident in how boys and girls experience puberty, timing differs, with girls beginning between 6 months and 2 years ahead of boys, depending on the specific pubertal characteristic.

- The onset of puberty depends on genes, gender, body fat, and stress, with the normal hormonal changes beginning at any time from 8 to 14 years.

- Puberty changes every part of the body and every aspect of sexuality; weight gain precedes increases in height, muscles, and sexuality.