9.3 Thinking, Fast and Slow

Body changes in adolescence are dramatic, but even more life-

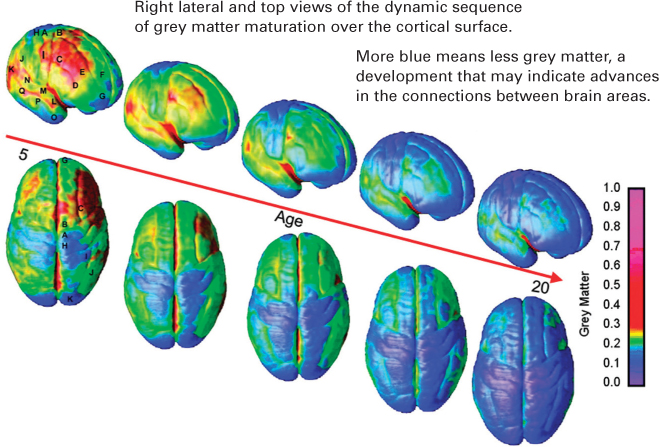

Brain Development

Like the other parts of the body, different parts of the brain grow at different rates (Blakemore, 2008). The limbic system, including the amygdala (where intense fear and excitement originate) matures before the prefrontal cortex (where planning, emotional regulation, and impulse control occur). As a result, the instinctual and emotional areas of the adolescent brain develop ahead of the reflective, analytic areas. Furthermore, pubertal hormones target the amygdala directly, whereas the cortex responds more to age and experience than to hormones. These neurobehavioural changes have been linked with youths’ increased behaviours in risk taking, sensation seeking, and recklessness (Dahl, 2004).

338

This is evident via brain scans. Emotional control, revealed by fMRI studies, is not fully developed until adulthood (Luna et al., 2010). When compared with 18-

Caution NeededThe fact that the frontal lobes (prefrontal cortex) are the last to mature may explain something that has long bewildered adults: Many adolescents are driven by the excitement of new experiences and sensations—

Laurence Steinberg is a noted expert on adolescent thinking. He is also a father.

When my son, Benjamin, was 14, he and three of his friends decided to sneak out of the house where they were spending the night and visit one of their girlfriends at around two in the morning. When they arrived at the girl’s house, they positioned themselves under her bedroom window, threw pebbles against her windowpanes.…The boys set off the house’s burglar alarm, which activated a siren and simultaneously sent a direct notification to the local police station, which dispatched a patrol car. When the siren went off, the boys ran down the street and right smack into the police car, which was heading to the girl’s home.…One of the boys was caught by the police and taken back to his home, where his parents were awakened and the boy questioned.

…After his near brush with the local police, Ben had returned to the house out of which he had snuck, where he slept soundly until I awakened him with an angry telephone call, telling him to gather his clothes and wait for me in front of his friend’s house. On our drive home, after delivering a long lecture about what he had done and about the dangers of running from armed police in the dark when they believe they may have interrupted a burglary, I paused.

“What were you thinking?” I asked.

“That’s the problem, Dad,” Ben replied, “I wasn’t.”

[Steinberg, 2004]

339

Steinberg agrees with his son. As he expresses it, “The problem is not that Ben’s decision-

This neurological shutdown is not reflected in questionnaires that ask teenagers to respond to hypothetical dilemmas. On those tests, most teenagers think carefully and answer correctly. They have been taught the risks of sex and drugs in biology or health classes in school, and they circle the right answers on multiple-

the prospect of visiting a hypothetical girl from class cannot possibly carry the excitement about the possibility of surprising someone you have a crush on with a visit in the middle of the night. It is easier to put on a hypothetical condom during an act of hypothetical sex than it is to put on a real one when one is in the throes of passion. It is easier to just say no to a hypothetical beer than it is to a cold frosty one on a summer night.

[Steinberg, 2004]

Brain immaturity is not the origin of every “troublesome adolescent behavior,” but it is true that teenage brains have underdeveloped “response inhibition, emotional regulation, and organization” (Sowell et al., 2007) because their prefrontal cortexes are immature.

The normal sequence of brain maturation (limbic system at puberty, then prefrontal cortex by the earlier 20s) combined with the early onset of puberty means that, for contemporary teenagers, emotions rule behaviour for years (Blakemore, 2008). The limbic system, unchecked by the slower-

It is not that the prefrontal cortex shuts down completely. In fact, it continues to mature throughout childhood and adolescence, and, when they think about it, adolescents are able to assess risks better than children are (Pfeiffer et al., 2011). However, when they think about it is crucial. The thoughtful parts of the adolescent brain are less synchronized with the limbic system than they were earlier in life, and thus emotions from the amygdala are less modulated than they once were (Pfeiffer et al., 2011). The balance and coordination among the various parts of the brain is off-

YELLOW DOG PRODUCTIONS/GETTY IMAGES

When stress, arousal, passion, sensory bombardment, drug intoxication, or deprivation is extreme, the adolescent brain is flooded with impulses. Teenagers brag about being so drunk they were “wasted,” “bombed,” “smashed”—a state most adults try to avoid and would be ashamed to admit. Unlike adults, some teenagers choose to spend a night without sleep, go through a day without eating, exercise in pain, or play hockey after a mild concussion.

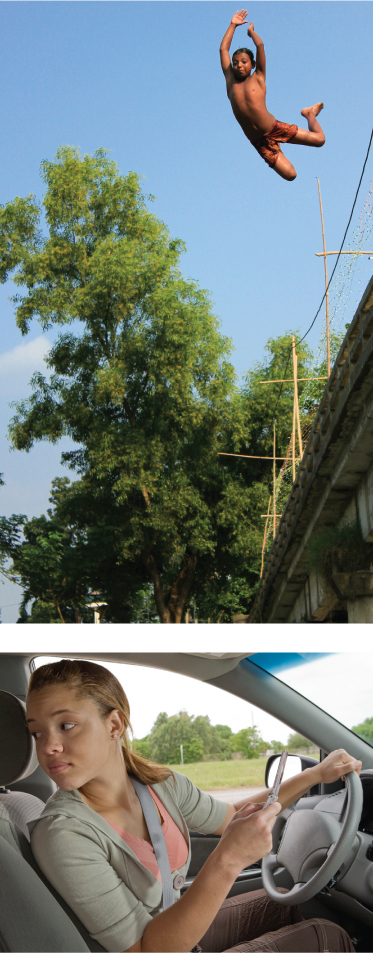

Risk and RewardEvery decision, from whether to eat a peach to when and where to enrol in college or university, requires balancing risk and reward, caution and attraction. For everyone, experiences, memories, emotions, and the prefrontal cortex help in choosing to avoid some actions and perform others. Neurological research finds that the reward parts of adolescents’ brains (the parts that respond to excitement and pleasure) are far stronger than the inhibition parts (the parts that urge caution) (Van Leijenhorst et al., 2010). The parts of the brain dedicated to analysis may be immature until years after the first hormonal rushes and sexual urges.

With regard to risk, by far the most common cause of teenage death is automobile accidents, and this is true despite teens having quicker reflexes and better vision than older people. A Statistics Canada report notes that of all the Canadians who were killed in motor-

340

Thoughtless impulses and poor decisions, rather than problems with reflexes or vision and hearing, are almost always to blame for these accidents. A major problem today is teens texting and talking on cellphones while driving. This has become such a problem in Canada that six provinces—

ESPECIALLY FOR Parents Worried About Their Teenager’s Risk Taking You remember the risky things you did at the same age, and you are alarmed by the possibility that your child will follow in your footsteps. What should you do?

It is normal to be concerned about your child’s behaviour. However, it is important to understand that you won’t be able to control your teenager. Set reasonable limits, and when the opportunity arises, be ready to listen and communicate.

Extensive research reveals that four measures have saved hundreds of lives of teenage drivers: (1) requiring more time between issuing a learner’s permit and granting a full licence, (2) no driving at night, (3) no teenage passengers, and (4) a zero-

Thinking About Oneself

During puberty, young people focus on themselves, in part because maturation of the brain heightens self-

EgocentrismYoung adolescents not only think intensely about themselves, they also think about what others think about them. Together, these two aspects of thought are called adolescent egocentrism, first described by David Elkind (1967). Egocentrism dominates in early adolescence, but it appears at times throughout the teen years, especially when the young person enters a new school or new peer group or goes off to college or university.

In egocentrism, adolescents regard themselves as unique, special, and much more socially significant (i.e., noticed by everyone) than they actually are. Egocentrism creates an imaginary audience in the minds of many adolescents. They believe they are at centre stage, with all eyes on them, and they imagine how others might react to their appearance and behaviour. The imaginary audience can cause teenagers to enter a crowded room as if they are the most attractive human beings alive. Take the case of Edgar, as described by his older sister:

Now in the 8th grade, Edgar has this idea that all the girls are looking at him in school. He got his first pimple about three months ago. I told him to wash it with my face soap but he refused, saying, “Not until I go to school to show it off.” He called the dentist, begging him to approve his braces now instead of waiting for a year. The perfect gifts for him have changed from action figures to a bottle of cologne, a chain, and a fitted baseball hat like the rappers wear.

[adapted from Eva, personal communication, 2007]

The reverse is also possible: Unlike with Edgar, egocentrism might cause adolescents to avoid scrutiny lest someone notice a blemish on their chin or make fun of their braces.

Egocentrism also leads adolescents to interpret everyone else’s behaviour as if it were a judgment on them. A stranger’s frown or a teacher’s critique could make a teenager conclude that “No one likes me” and then deduce that “I am unlovable” or even to claim that “I can’t leave the house.” More positive casual reactions—

341

Elkind named several aspects of adolescent egocentrism, including the personal fable and the invincibility fable, which often appear together (Alberts et al., 2007). The personal fable is the belief that one is unique and destined to have a heroic, fabled, even legendary life. Some 12-

Formal Operational Thought

In his theory of cognitive development, Jean Piaget described a shift in adolescence from concrete operational thought to what he called formal operational thought. Adolescents begin to consider abstractions and can make “assumptions that have no necessary relation to reality” (Piaget, 1972).

One way to distinguish formal from concrete thinking is to compare curricula in primary school and high school. For example in math, younger children multiply real numbers, such as 4 × 3 × 8; adolescents multiply abstract (algebraic) numbers, such as (2x)(3y) or (25xy2)(3zy3). In social studies, younger children learn about other cultures by reading about daily life or experiencing aspects of the culture themselves—

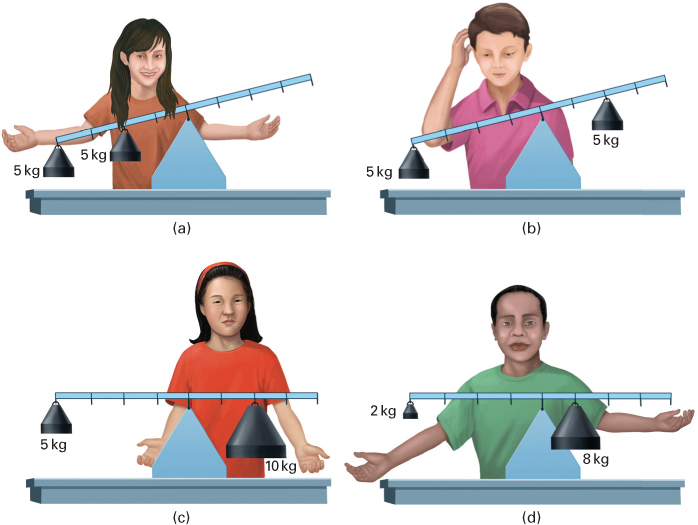

Piaget’s ExperimentsPiaget and his colleagues devised a number of tasks to assess formal operational thought (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958). In one experiment (diagrammed in Figure 9.2), children of many ages balance a scale by hooking weights onto the scale’s arms. To master this task, they must realize that the weights’ heaviness and distance from the centre interact reciprocally to affect balance.

342

The concept of balancing (that a heavy weight close to the centre could be balanced by a lighter weight farther from the centre on the other side) was completely beyond the 3-

Hypothetical-

The adolescent…thinks beyond the present and forms theories about everything, delighting especially in considerations of that which is not.

[Piaget, 1972]

Adolescents are primed to engage in hypothetical thought, reasoning about if–

If all mammals can walk,

And whales are mammals,

Can whales walk?

Younger adolescents often answer “No!” They know that whales swim, not walk, so the logic escapes them. Some adolescents answer “Yes.” They understand the concept of if:

Possibility no longer appears merely as an extension of an empirical situation or of action actually performed. Instead, it is reality that is now secondary to possibility.

[Inhelder & Piaget, 1958; emphasis in original]

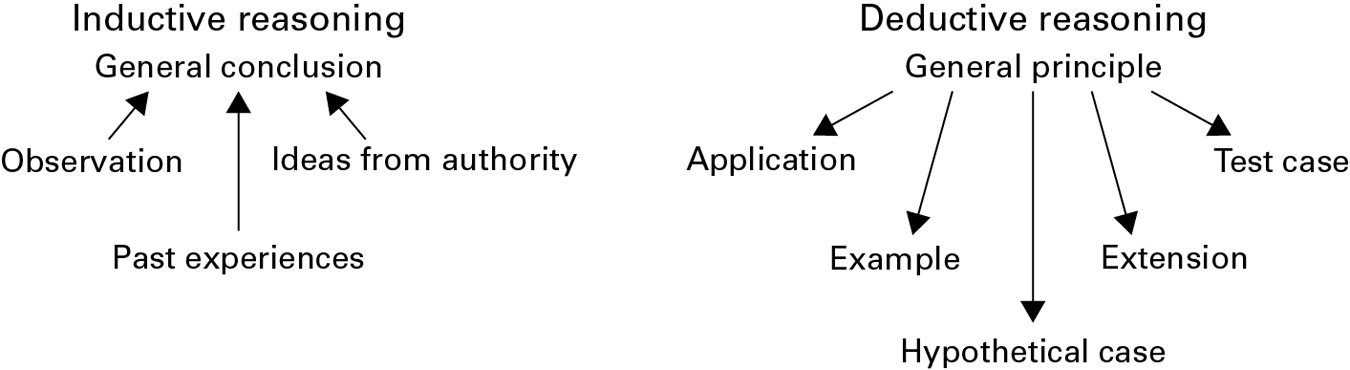

In developing the capacity to think hypothetically, adolescents gradually become capable of deductive reasoning, or top-

343

Two Modes of Thinking

The fact that adolescents and adults can use hypothetical-

In adolescence, abstract logic is counterbalanced by the increasing power of intuitive thinking. A dual-process model of adolescent cognition has been formulated (Albert & Steinberg, 2011). Various scholars choose different terms and sometimes distinct definitions of the two processes of thinking, such as: intuitive and analytic, implicit and explicit, creative and factual, contextualized and decontextualized, unconscious and conscious, hot and cold, gist and quantitative, emotional and intellectual, experiential and rational, and system 1 and system 2.

The thinking described by the first half of each pair (intuitive, implicit, creative, contextualized, unconscious, hot, gist, emotional, experiential, system 1) is preferred in everyday life. Sometimes, however, circumstances and experience compel people to use the second mode, when deeper thought is demanded. Because of the discrepancy between the maturation of the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex, adolescents are particularly likely to use intuition, not analysis (Gerrard et al., 2008). Intuitive thought begins with a belief, assumption, or general rule (called a heuristic) rather than with logic. Intuition is quick and powerful; it feels “right.” Analytic thought is the formal, logical, hypothetical-

When the two modes of thinking conflict, people sometimes use one mode and sometimes the other. Experiences and role models influence the choice. For example, one study found that when adolescents enter a multicultural high school, some rely on old stereotypes and others reassess their thoughts to consider new perspectives. Which of these two modes of thinking predominates depends on the students’ specific experiences and on the attitudes of the adults in the school (Crisp & Turner, 2011).

Comparing Intuition and AnalysisPaul Klaczynski conducted dozens of studies comparing the thinking of children, young adolescents, and older adolescents (usually 9-

Timothy is very good-

Based on this [description], rank each statement in terms of how likely it is to be true.…The most likely statement should get a 1. The least likely statement should get a 6.

_________ Timothy has a girlfriend.

_________ Timothy is an athlete.

_________ Timothy is popular and an athlete.

_________ Timothy is a teacher’s pet and has a girlfriend.

_________ Timothy is a teacher’s pet.

_________ Timothy is popular.

344

In ranking these statements, most adolescents (73 percent) made at least one analytic error, ranking a double statement (e.g., popular and an athlete) as more likely than a single statement included in it (popular or an athlete). They intuitively jumped to the more inclusive statement, rather than sticking to logic. In many other studies, adults often make the same mistake (Kahneman, 2011).

Klaczynski found that almost all adolescents were analytical and logical on some of the 19 problems but not on others. Logical thinking improved with age and education, although not with IQ. In other words, being smarter as measured by an intelligence test did not advance logic as much as did having more experience, in school and in life. Klaczynski (2001) concluded that, even though teenagers can use logic, “most adolescents do not demonstrate a level of performance commensurate with their abilities” (p. 854).

Preferring EmotionsWhat would motivate adolescents to use—

Dozens of experiments and extensive theorizing have found some answers (Albert & Steinberg, 2011; Kahneman, 2011). Essentially, analytic thought is more difficult than intuition, and it requires examination of comforting, familiar prejudices.

Once people of any age reach an emotional conclusion (sometimes called a “gut feeling”), they resist changing their minds. As people gain experience in making decisions and thinking things through, they become better at knowing when analysis is needed (Milkman et al., 2009).

For example, in contrast to younger students, older adolescents are more suspicious of authority and more likely to consider mitigating circumstances when judging the legitimacy of a rule (Klaczynski, 2011). Both suspicion of authority and awareness of context signify advances in reasoning, but both also complicate simple issues.

KEY Points

- Uneven brain development characterizes adolescence, with the limbic system developing faster than the prefrontal cortex.

- Young adolescents are often egocentric, thinking of themselves as invincible and performing for an imaginary audience.

- Adolescents are also capable of logical, hypothetical thought, what Piaget described as formal operational thinking.

- Both emotional intuition and logical analysis are stronger in adolescence than earlier in life. Adolescents usually prefer the former because it is faster and easier.