9.4 Teaching and Learning

What does our knowledge of adolescent thought imply about education? Which curricula and school structures (single-

345

Given personal and cultural variations, no specific school curriculum, structure, or teaching method is best for everyone. Various scientists, nations, schools, and teachers try many strategies. To analyze these, we begin with definitions and facts.

Definitions and Facts

Each year of schooling advances human potential, as recognized by leaders and scholars in every nation and discipline. As you have read, adolescents are capable of deep and wide-

Secondary education—traditionally Grades 7 through 12 (Grade 11 in Quebec)—denotes the school years after elementary or grade school (known as primary education) and before college or university (known as tertiary education, or more commonly as post-

Secondary EducationSecondary education is important to adults’ health. Data on almost every ailment, from every nation and ethnic group, confirm that high school graduation correlates with better health. Some of the reasons are only indirectly related to education (e.g., income and place of residence), but even when such factors are taken into account, health improves with education. Even such a seemingly unrelated condition as serious hearing loss in late adulthood is twice as common among those who never graduated from high school as it is among high school graduates (National Center for Health Statistics, 2010).

Secondary education is also important for a nation’s economic growth, since that growth depends on highly educated workers. Partly because political leaders recognize that educated adults advance national wealth and health, every nation is increasing the number of students in secondary schools. Education is compulsory until at least age 12 almost everywhere (UNESCO, 2008), and several national leaders advocate compulsory education until age 18 or high school graduation, whichever comes first.

ESPECIALLY FOR Middle School Teachers You think your lessons are interesting, but many of your students seem disinterested, distract their fellow classmates, or simply tune you out. What do you do?

Students need both challenge and involvement; avoid lessons that are too easy or too passive. Create small groups; assign oral reports, debates, role-plays, and so on. Remember that adolescents like to hear each other’s thoughts and their own voices.

Middle SchoolMiddle school is a challenging time for students. The average grades on report cards fall, achievement tests show less learning each year, students are less motivated to study and learn, and behavioural problems rise. Do these middle school experiences matter for later achievement? One team believes so: “Long-

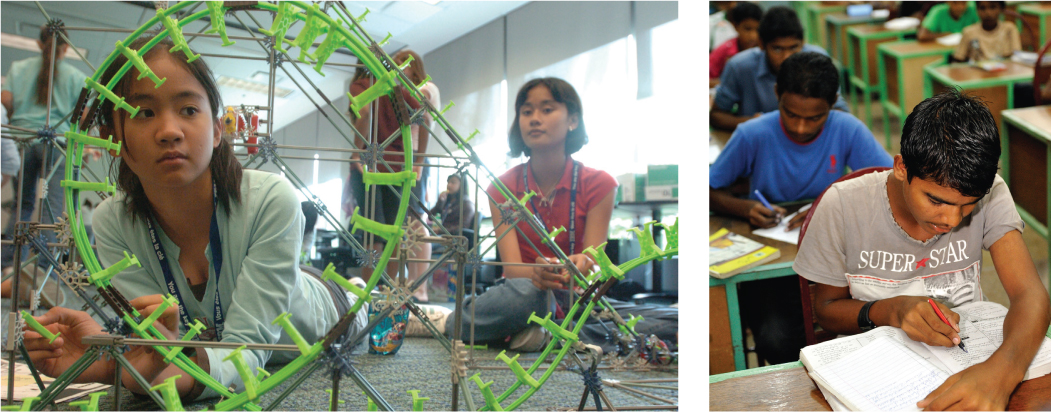

IMAGEBROKER/ALAMY

Puberty itself is part of the problem. At least for other animals, especially when under stress, learning slows down at puberty (McCormick et al., 2010). The same is probably true for humans, who experience biological and psychological stresses during puberty. However, many experts do not believe stresses of puberty are the main reasons learning suffers in early adolescence. Instead, they blame the organizational structure of many middle schools (Meece & Eccles, 2010). To be specific, unlike in primary school, where each teacher is responsible for one classroom of children, middle school teachers are not connected to any small group. Instead, they specialize in an academic subject, taught to hundreds of students each year. This makes them impersonal and distant: Students learn less and risk more because no one teacher is aware of their actions (Crosnoe et al., 2004). It is ironic that just when egocentrism leads young people to feelings of shame or fantasies of stardom (the imaginary audience), many middle schools require them to change rooms, teachers, and classmates every 40 minutes or so. That makes public acclaim and personal recognition difficult.

346

Since public acclaim is elusive, many middle school students seek acceptance from their peers. Bullying increases, appearance becomes important, status symbols are displayed (from gang colours to expensive shoes), and sexual conquests are flaunted, with boys bragging and girls gaining status if they are dating an older person. Values change too: In Grade 4 the “coolest” peers are good students; by Grade 8, cool peers are not involved in school and are likely to be antisocial (not kind, antagonistic to adults) (Galván et al., 2011). Of course, much depends on the cultural context, but almost every middle school student seeks peer approval in ways that adults disapprove of (Véronneau & Dishion, 2010).

Motivation

A cognitive perspective on development highlights the academic disengagement typical of many middle school students, and tries to understand its causes and seek effective prevention. Some reasons have already been suggested: puberty, alienation from teachers, reliance on peers. But an additional reason may be adolescents’ assumptions about their potential and how to achieve what they wish.

If they believe in the entity approach to intelligence (i.e., that ability is innate, a fixed quantity present at birth), then they think it is hopeless to study, especially in subjects that do not come easily. All they can do is accept their deficiencies, such as for math, or writing, or languages. They are convinced that they are incapable of mastering particular skill sets and this will never change, making comments such as, “I’m just not good at math.” This entity belief reduces stress but also reduces achievement.

By contrast, if students believe in the incremental approach to intelligence (i.e., that ability increases if they work on it), then they will pay attention, participate in class, study, complete their homework, and so on. That is called mastery motivation.

This is not just a hypothesis. In the first year of middle school, students with entity beliefs tend not to be academically successful, whereas those with mastery motivation show achievement gains (Blackwell et al., 2007). In one study, some students in their first year of middle school took part in a program in which they were taught eight lessons designed to convey the idea that being smart was incremental. For instance, they were taught ways to “Grow Your Intelligence,” as one segment of the program was called. Those students gained—

347

Teachers themselves were surprised at the effect. Among the typical comments was a teacher explaining that a boy

who never puts in any extra effort and doesn’t turn in homework on time, actually stayed up late working for hours to finish an assignment early so I could review it and give him a chance to revise it. He earned a B+…he had been getting C’s and lower.

[quoted in Blackwell et al., 2007]

The concept that skills and intelligence can be mastered motivates the learning of social skills as well as academic subjects (Olson & Dweck, 2008). This makes it particularly important in adolescence, when peers are so important.

The contrast between the entity and incremental approaches is apparent not only for individual adolescents, but also for teachers, parents, schools, and cultures. If a school is structured so that children individually compete with each another rather than in cooperative groups, then individuals who score low are likely to cope by endorsing the entity theory (Eccles & Roeser, 2011). By contrast, when teachers and students are supportive of each other’s learning, the belief in mastery is evident. (Patrick et al., 2011).

According to international comparisons, educational systems that track students into higher or lower classes, that expel students who are not learning, and that allow competition between schools for the brightest students (all reflecting entity, not incremental, theory) are also school systems with lower average achievement and a larger gap between the scores of students at the highest and lowest score quartiles (Organisation for Economic Co-

Before assuming that all middle school students are disengaged, remember that adolescents vary in every aspect of development, including motivation. A study of student emotional and academic engagement from Grade 5 to Grade 8 found that, as expected, the overall direction was less engagement. Yet, a distinct group (about 18 percent) was highly engaged throughout, and only a few (about 5 percent) decreased drastically in engagement from Grades 5 to 8. The disengaged students were more often minority boys from low-

School Transitions

Every transition is stressful. The most difficult times are the first year of middle school, the first year of high school, and the first year of college or university. The larger and less personal the new institution is, and the more egocentric the student is, the more difficult the transition.

Strangers in SchoolsWhen students enter a new school with classmates and customs unlike those in their old school, they often feel alienated, fearing failure (Benner & Graham, 2007). This is especially true for students entering large schools from more intimate ones. Some research suggests that school enrolment should be 600 or fewer students, although many urban high schools boast more than 1000 students. When schools are that large, many students are strangers to each other. In addition, for most (though not all) students, engagement decreases as school size increases (Weiss et al., 2010). However, school size may be less problematic than school organization, such as having many different students for each teacher (too impersonal) and weak school norms, loyalty, and spirit (a problem for large schools) (Gottfredson & DiPietro, 2011).

348

The transition to a new school is even more challenging for immigrant students. In a study of 125 Canadian youths (aged 11 to 19 years) from immigrant families in five provinces (Alberta, British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec), students cited several challenges in adjusting to their new school environment. Most prominent among these challenges were the structure of the school (i.e., having to rotate from classroom to classroom), class assignments such as group projects, and their inability to speak either official language (English or French) (Chuang & Canadian Immigrant Settlement Sector Alliance, 2009).

Another important problem is stereotype threat, the anxiety-

A study of the transition from middle to high school confirmed that personal relationships are crucial in helping students adapt to unfamiliar circumstances: Students are less likely to drop out if they have friends in the new school and teachers who encourage learning. School policies (e.g., class placement, group discussions) can facilitate such relationships (Langenkamp, 2010).

Students already at risk of emotional problems may suffer more than others because of the transition; anxiety, depression, and quitting may result. Worse psychological disorders may occur. As one expert notes, “Depression, self-

Of course, transitions are not the only cause of adolescent pathology; hormones, body changes, sexual experiences, family conflict, and cultural expectations also contribute. In addition, puberty may activate genes that predispose a person to mental disorders (Erath et al., 2009), and the sequence of brain development may cause emotional difficulties. Nonetheless, for many reasons, adolescent newcomers to a school community need extra support to learn well.

To eliminate one transition, some school systems and even some countries (e.g., Finland) have children attend the same institution from Grade 1 through Grades 8 and 9. In Canada and the United States, districts vary in terms of when and whether children leave primary school. When the move occurs early, after Grade 4 (as opposed to after Grade 5, 6, or 7), or not until after Grade 8, children seem to learn more (Schwartz et al., 2011).

Some small private schools eliminate transitions by having one school from kindergarten through Grade 12. This may facilitate learning, or it may make it more difficult for graduates to adjust to college or university, to the workplace, or to a new community.

BullyingBullying decreases each year of elementary school, perhaps because students learn from classmates and teachers that there are better ways to interact with other children. However, many studies find that bullying increases in the first year of middle school and again in the first year of high school. This occurs between the sexes as well as within them, with girls likely to bully other girls they perceive as sexual rivals, and boys likely to bully other boys they perceive as weaker. Beyond that, students new to a larger school may feel they need to assert themselves. Some students, especially bully-

349

Although the causes of all forms of bullying seem similar, each carries its own sting. All bullying is harmful when the self-

All forms of bullying are affected by the school climate. When students consider their school a good place to be—

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Misconceptions about Bullying

Amanda Todd was born on November 26, 1996. She committed suicide on October 10, 2012, one month shy of her 16th birthday. But one month before this terrible end, Amanda powerfully chronicled her tragic life events on YouTube.

Amanda was twelve years old when she was befriended by a boy online. Flattered by his comments, Amanda lifted up her top and flashed the person via her webcam. This single moment of indiscretion followed her for three years before she ended her life. In Gillian Shaw’s interview with Amanda Todd’s mother for the Vancouver Sun, Carol Todd stated,

The Internet stalker she flashed kept stalking her. Every time she moved schools he would go undercover and become a Facebook friend. What the guy did was he went online to the kids who went to (the new school) and said that he was going to be a new student—

The cyberstalker then sent the video and pictures of Amanda to everybody at her new school—

PREVNet is a network of 69 Canadian researchers and 55 national youth-

As PREVNet has reported, ongoing misunderstanding and misconceptions about bullying hinder the efforts being made to eliminate bullying. First, bullying does cause serious harm, and it has short-

Another misconception about bullying is that children who bully will grow out of it. Childhood bullies who are not identified early and do not receive intervention are more likely to bully in adolescence and adulthood. Their bullying behaviour progresses into more sophisticated forms over time as their thinking and social skills develop, and they become even more aware of their victims’ vulnerabilities. These behaviours include sexual and work harassment, dating violence, marital abuse, child abuse, and elder abuse.

Children who are victimized cannot stop the bullying on their own. Due to the victim’s vulnerable position in the relationship, adult intervention is required to correct the power imbalance. Children and parents may even need to report bullying to various adults in authority, such as a teacher or principal.

Along similar lines, telling children to fight back may worsen the situation. Research has shown that children who use aggressive strategies to combat their victimizer tend to experience longer and more severe bullying interactions. As a result, all adults, including parents, teachers, and other adults in the community, are responsible for supporting children in developing effective social skills and learning to respect each other, regardless of ethnicity, gender, or citizenship (PREVNet.ca, n.d.).

350

Succeeding in High School

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” is a question often asked of children. Younger children often aspire to a career that fewer than one in a million will obtain—

Measuring Practical CognitionEmployers hope their future employees will have learned in secondary school how to think, explain, write, concentrate, and get along with other people. Those skills are hard to measure, especially on the two international tests described in Chapter 7, the PIRLS and the TIMSS.

The PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment), also mentioned in Chapter 7, was designed to measure the cognitive abilities needed in adult life. The PISA is taken by 15-

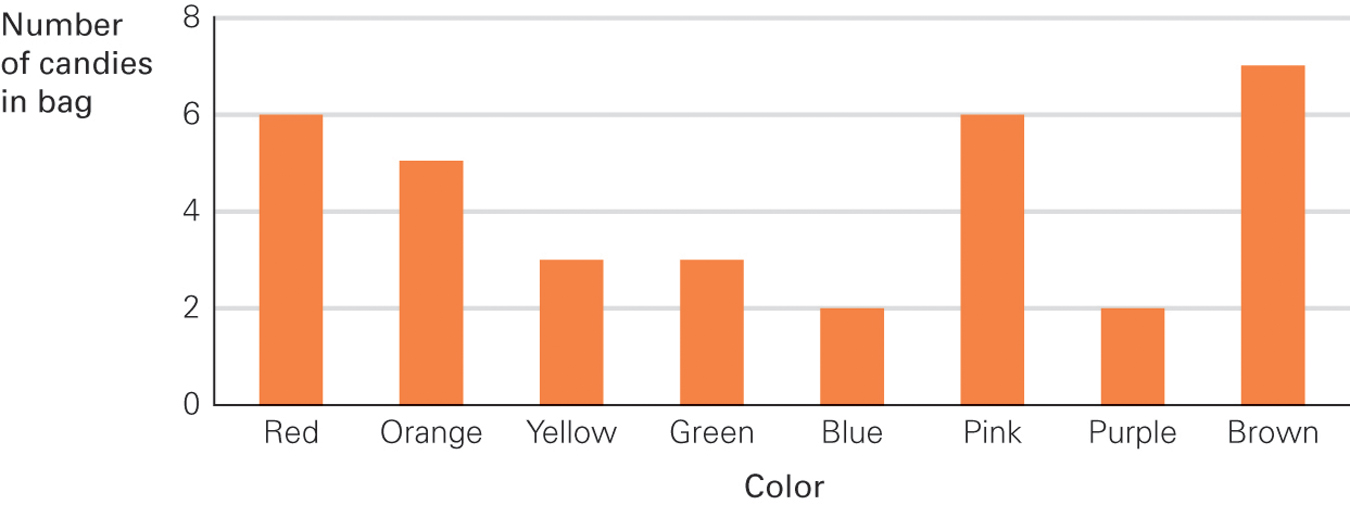

Robert’s mother lets him pick one candy from a bag. He can’t see the candies. The number of candies of each color in the bag is shown in the following graph.

What is the probability that Robert will pick a red candy?

A. 10% B. 20% C. 25% D. 50%

For that and the other questions on the PISA, the calculations are quite simple—

In 2009, on the PISA overall (reading, science, and math), China, Finland, and Korea were at the top; Canada was close to the top; and the United States scored near average (see TABLE 9.1 for math scores). Analysis of nations and scores on the PISA finds four factors that correlate with high achievement (OECD, 2010a):

- Leaders, parents, and citizens overall value education, with individualized approaches to learning so that all students learn what they need.

- Standards are high and clear, so every student knows what he or she must do, with a focus on the acquisition of complex, higher order thinking skills.

- Teachers and administrators are valued, given considerable discretion in determining content and sufficient salary as well as time for collaboration.

- Learning is prioritized across the entire system, with high-

quality teachers working in the most challenging environments.

351

| Nation | Score | Nation | Score | Nation | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China Shanghai | 600/n/a | Denmark | 503/513 | Greece | 466/459 |

| Singapore | 562/n/a | Norway | 498/490 | Israel | 447/442 |

| Hong Kong | 555/547 | France | 497/496 | Turkey | 445/424 |

| South Korea | 546/547 | Austria | 496/505 | Uruguay | 427/427 |

| Chinese Taipei | 543/549 | Poland | 495/495 | Romania | 427/415 |

| Finland | 541/548 | Sweden | 494/502 | Chile | 421/411 |

| Switzerland | 534/530 | Czech Republic | 493/510 | Thailand | 419/417 |

| Japan | 529/523 | United Kingdom | 492/495 | Mexico | 419/406 |

| Canada | 527/527 | Hungary | 490/491 | Argentina | 388/381 |

| Netherlands | 526/531 | Ireland | 487/501 | Jordan | 387/384 |

| New Zealand | 519/522 | United States | 487/474 | Brazil | 386/370 |

| Belgium | 515/520 | Portugal | 487/466 | Colombia | 381/370 |

| Australia | 514/520 | Spain | 483/480 | Indonesia | 371/391 |

| Germany | 513/504 | Italy | 483/462 | Tunisia | 371/365 |

| Iceland | 507/506 | Russia | 468/476 | ||

| Source: PISA, 2009. | |||||

Practical Knowledge Tested by the PISA The PISA is taken by 15-

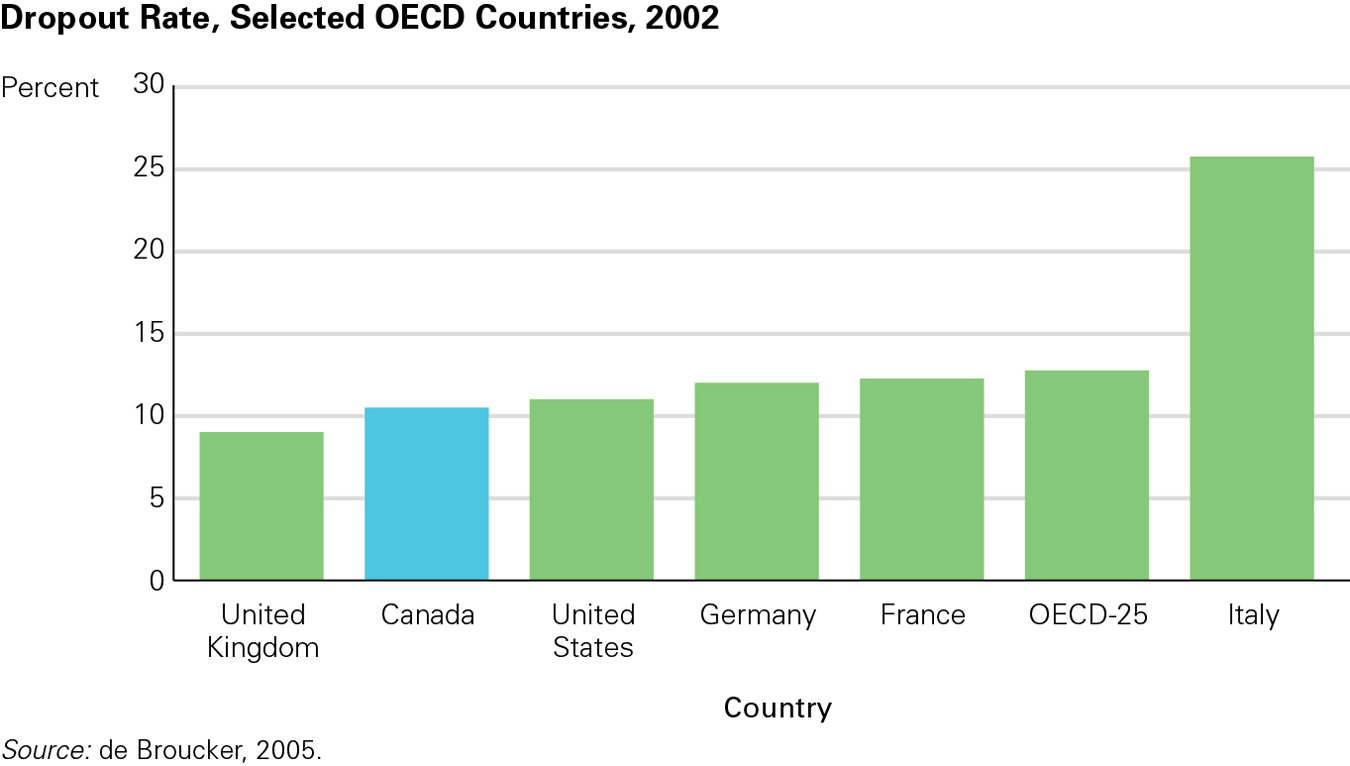

Dropout RatesIndications from the PISA and from international comparisons of high school dropout rates suggest that secondary education can be improved for those who do not go to college or university. Surprisingly, students who are capable of passing their classes drop out as often as those who are less capable, at least as measured on IQ tests.

Persistence, engagement, and motivation seem more crucial for high school success than is intellectual ability (Archambault et al., 2009). One study that measured engagement and motivation reported developmental differences: Students were most motivated and engaged in primary school, somewhat engaged in college or university, but least engaged in secondary school (Martin, 2009).

According to a study conducted in 2002, Canada has been more successful at reducing dropout rates than many other developed countries. Canada’s dropout rate was almost 4 points lower than the average for the 25 OECD industrialized countries (see Figure 9.4). Except for Great Britain, Canada had the lowest dropout rate among the G7 nations that year.

352

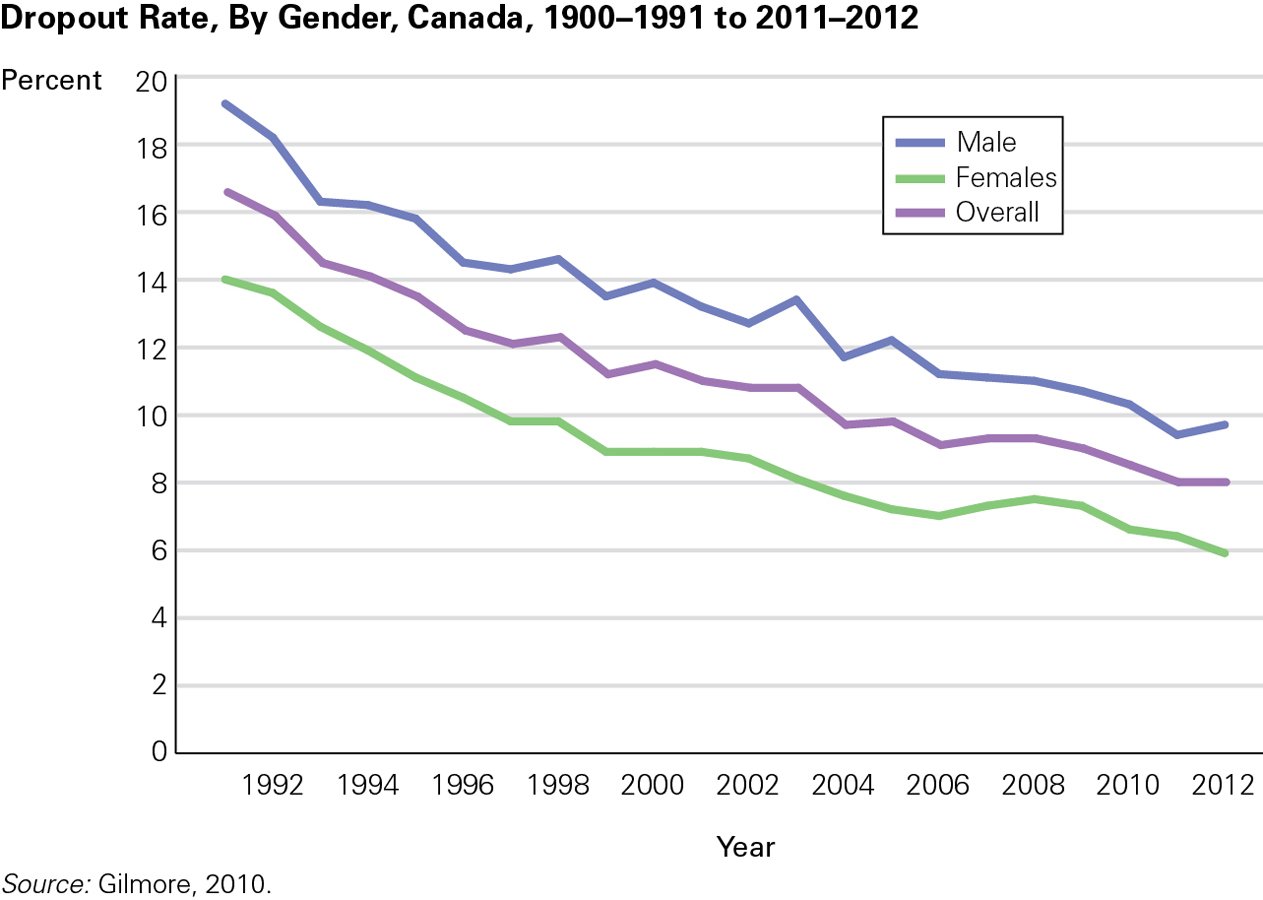

According to Statistics Canada, the high school dropout rate decreased significantly over the last 20 years—

Generally, Canadian dropout rates tend to be somewhat higher in rural areas, in Quebec, and in the Western provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. However, between 2007 and 2010, the three territories had the highest dropout rates in Canada by far: 16 percent in the Yukon, 30 percent in the Northwest Territories, and 50 percent in Nunavut (Gilmore, 2010). As noted in Chapter 7, this reflects the generally high dropout rate among Aboriginal peoples in Canada, which in 2006 reached 40 percent.

On the plus side, dropout rates for immigrant youth (6 percent) were lower than for Canadian-

ESPECIALLY FOR High School Teachers You are much more interested in the nuances and controversies than in the basic facts of your subject, but you know that your students need to learn the required curriculum and their final grades will have a major impact on their futures. What should you do?

Use a variety of strategies to teach the information your students need to master as a foundation for the exciting and innovative topics you want to teach. This will help your students feel a personal connection to the information, they may learn more, and student achievement should improve.

Two good reasons for getting a high school diploma are that graduates usually make more money than students who drop out, and they also have better rates of employment during tough economic times. For example, in the fiscal year 2009/2010, even those people who had dropped out of high school but were employed full time and worked longer hours than high school graduates earned on average $70 less per week than the graduates did. Moreover, during the recession of 2008 to 2009, employment rates decreased by 10 percent for those without a high school diploma but only by 4 percent for graduates (Statistics Canada, 2013g).

Innovative Programs in CanadaIn high schools across Canada, guidance counsellors work to support students in realizing their vocations. Their goal is try to find ways to keep students in school and help them plan for the future. As provinces and territories acknowledge the individual differences among students, innovative programs are being developed that are customized to students’ strengths and learning needs. These governmental efforts are aimed at increasing graduation rates.

353

MELANIE STETSON FREEMAN/THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR/GETTY IMAGES

As an example, Aberta Education identified the outcomes for students’ programs of study in consultation with educators, business, industry, and other community organizations. While these outcomes are established at the provincial level and applied to all students, how they are implemented is individualized to each student or group of students. For example, the Career and Technology Studies (CTS) program has been designed around career pathways. Currently, there are five clusters: (1) business, administration, finance, and information technology; (2) health, recreation, and human services; (3) media, design, and communication arts; (4) natural resources; and (5) trades, manufacturing, and transportation. Students can take other courses that will enhance not only their academic skills and learning, but also their competencies in the workforce, thus increasing chances of their success in transitioning into employment or other education (college, university) and training opportunities (Alberta Education, 2013).

In Ontario, high schools are partnering with local communities, employers, colleges, universities, and training centres to foster students’ interests. For example, students can enrol in programs such as specialist high skills majors, cooperative education, and dual credit programs.

Specialist high skills majors are 8 to 10 courses in a specific field, such as the economic sector, agriculture, or information technology. Along with their coursework, students complete industry certifications (including first aid and CPR qualifications), and learn important job skills. Students who choose this track include those who want to do an apprenticeship, training, or workforce program, or attend college or university. The program gives students an opportunity to identify and explore potential careers early on.

Cooperative education is similar to the specialist high skills majors as it combines both classroom and workplace learning. However, in this track, students complete at least two co-

354

Lastly, the dual credit programs provide opportunities for students to earn both their high school diploma as well as credits toward a college diploma or apprenticeship certification. Students in this track participate in college courses. This track is especially meaningful for students who may be at risk of not graduating from high school or those who had left high school but are now deciding to return (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2012).

Alberta and Ontario are just two examples of provinces whose ministries of education are building meaningful learning experiences for students, which will ease their transition to the next stage of their lives, whether it be post-

The College-

What are the rates of registration in universities and colleges? Data from the Postsecondary Student Information System (PSIS) includes information from 1992 to 2007 for universities and 2000 to 2006 for colleges across Canada. In 2006, over 1.6 million students were registered in colleges and universities, with about 400 000 graduating that year. The majority of the students (75 percent) were between the ages of 17 and 27. There was little gender difference by age for both college and university graduates (Dale, 2013).

Aboriginal youth are one of the fastest growing age groups in Canada; there are more than 560 000 Aboriginal youth under the age of 25. However, only 8 percent of Aboriginals complete a university degree, one third of the Canadian average (Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, 2013). As a result, Canada’s universities have launched an online program specifically for Aboriginal students to provide them with better access to information about various relevant programs and services on campuses nationwide. The Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada developed the searchable database, which includes information about 286 academic programs designed for Aboriginal students. It also includes other useful information about financial assistance, housing, counselling, cultural activities, availability of Elders, and gathering spaces and mentoring.

Praising Adolescent Cognition

It is easy to conclude that adolescent thinking is immature and self-

Benefits of Adolescent Brain DevelopmentWith increased myelination and slower inhibition, reactions become lightning fast; such speed is valuable in cognition as well as in other domains. For instance, adolescent athletes are potential superstars, not only quick but fearless as they steal a base, skate at full speed to the net, tackle a fullback, or race when their lungs feel about to burst. Ideally, coaches have the wisdom to channel such bravery.

Furthermore, as the reward areas of the brain activate and the production of certain mood-

Before another wave of pruning (at about age 18), and before the brain becomes fully mature (at about age 25), “young brains have both fast-

355

Synaptic growth enhances moral development as well. Adolescents question their elders and seek to forge their own standards. In short, several aspects of adolescent brain development can be positive. The fact that the prefrontal cortex is still developing “confers benefits as well as risks. It helps explain the creativity of adolescence and early adulthood, before the brain becomes set in its ways” (Monastersky, 2007, p. A-

Even those aspects of adolescent thinking that could be considered negative, such as a tendency toward intutitive thinking and egocentrism, may have their advantages. At every age, the best thinking may be “fast and frugal” (Gigerenzer, 2008). Weighing alternatives, and thinking of possibilities, is sometimes paralyzing. Few adolescents have that problem.

As for egocentrism, it protects the self each time an individual enters a new environmental context or life situation (Schwartz et al., 2008). Young adolescents who feel psychologically invincible (not harmed by others’ judgments) tend to be resilient and less likely to be depressed (Hill et al., 2012).

Of course, if a criticism from a peer cuts too deep, friends and family need to help the young person gain perspective, but difficult experiences build resilience as long as they are not overwhelming (Seery, 2011). All the sudden and erratic body changes of puberty that we have described are easier if a person feels special and strong.

What Adults Can DoDoes learning during adolescence matter when considering the entire life span? For individuals, the answer is a resounding yes. Not only health, but also almost every other indicator of a good life—

For society, the answer is yes as well. Nations gain from the quality of secondary education. For example, the cognitive skills that boost economic development are creativity, flexibility, and analytic ability; they allow innovation and mastery of new technology. When nations raise their human capital by having more adults with those skills, their economies prosper (Cohen & Soto, 2007).

Those cognitive abilities that nations need in the twenty-

KEY Points

- Secondary education is crucial for personal health and for national economic development.

- Many students become alienated from learning during middle school; middle schools are not usually organized to encourage relationships between teachers and students.

- Transitions to new schools are always challenging, as illustrated by the increase in bullying, especially cyberbullying, as middle school begins.

- International tests such as the PISA indicate that Canadian students are achieving well in math, reading, and science.

- Adolescents are capable of intense learning of new ideas and of questioning traditional beliefs.

356