Human Relationships

The adolescent’s search for identity may seem self-

As at every age, adolescents are social beings, dependent on other people to validate whatever identity they seek. Adults as well as peers have an impact: Relationships at home, in school, or with peers correlate with relationships in the other two areas. Likewise, conflict in one setting increases conflict and affects mood in the other settings (Timmons & Margolin, 2015; Flook & Fuligni, 2008; Chung et al. 2011).

With Adults

Adolescence is often characterized as a time when children distance themselves from their elders. That is only half true. Adult influence is less obvious but no less important.

PARENTS Parent–

Conflict peaks in early adolescence, especially with mothers. Typical are repeated, petty arguments (more nagging than fighting) about routine, day-

Each generation tends to misjudge the other, which may add to the conflict. Parents think their offspring resent them more than they actually do, and adolescents imagine their parents want to dominate them more than they actually do (Sillars et al., 2010).

Unspoken concerns need to be aired so that both generations better understand each other. Imagine a parent seeing filthy socks on the living room floor. The parent might interpret that as deliberate disrespect and react angrily to the attack, yelling “Put those socks in the hamper right now!” But perhaps the adolescent was merely egocentric and distracted, oblivious to the parent’s desire for a neat house. If so, then the parent could merely sigh and put the socks in the child’s room.

Some bickering may indicate a healthy family, since close relationships almost always include conflict. A study of mothers and their adolescents suggested that “although too much anger may be harmful . . . some expression of anger may be adaptive” (Hofer et al., 2013, p. 276).

The parent–

You already know that authoritative parenting is best for children and that uninvolved parenting is worst. This continues in adolescence. Neglect is always destructive and authoritarian parenting can boomerang, resulting in teenagers who lie or leave. The effect is reciprocal: Teenagers of authoritarian parents become secretive, which makes the parents even more authoritarian (Kerr et al., 2012).

CLOSENESS WITHIN THE FAMILY More important than conflict may be family closeness, which has four aspects:

Communication (Do family members talk openly with one another?)

Support (Do they rely on one another?)

Connectedness (How emotionally close are they?)

Control (Do parents encourage or limit adolescent autonomy?)

No social scientist doubts that the first two, communication and support, are helpful, perhaps essential, for healthy development. Patterns set in place during childhood continue, ideally buffering the turbulence of adolescence (Amsel & Smetana, 2011; Laursen & Collins, 2009).

Regarding the next two, connectedness and control, consequences vary and observers differ in what they see. How do you react to this example, written by one of my students?

I got pregnant when I was sixteen years old, and if it weren’t for the support of my parents, I would probably not have my son. And if they hadn’t taken care of him, I wouldn’t have been able to finish high school or attend college. My parents also helped me overcome the shame that I felt when . . . my aunts, uncles, and especially my grandparents found out that I was pregnant.

[I., personal communication]

My student is grateful to her parents, but did teenage motherhood give her parents too much control, requiring her to depend on them instead of seeking her identity? Indeed, had they unconsciously encouraged pregnancy, by permitting her to be with her boyfriend but not explaining contraception? The child’s father was no longer in her life when I knew her; was that an unhealthy disconnection?

An added complexity is that this young woman’s parents had emigrated from South America. Cultural expectations affect everyone’s responses, so her dependence may have been normative in her culture but not elsewhere. A longitudinal study of nonimmigrant adolescent mothers in the United States found that most (not all) fared best if their parents were supportive but did not take over child care (Borkowski et al., 2007).

Note that family relationships for this young mother, as potentially for everyone, include other relatives. In this case, the parents buffered the relationship between the 16-

Sometimes parents ask the adolescent’s aunt or uncle to discuss taboo topics, such as sex or delinquency that make parents uncomfortable (Milardo, 2009). Links between teenagers and relatives are especially common in developing nations and among immigrant groups for two reasons: (1) Relatives often live together or nearby, and (2) cultural values make family central.

parental monitoring

Parents’ ongoing awareness of what their children are doing, where, and with whom.

A related issue that is not as simple as it appears is parental monitoring—that is, parental knowledge about each child’s whereabouts, activities, and companions. Many studies have shown that parental monitoring helps adolescents become confident, well-

Video: Parenting in Adolescence examines how family structure can help or hinder parent–

However, researchers note that monitoring is a mutual process, with adults who care and adolescents who communicate. If the parents are cold, strict, and punitive, demands for information may provoke deception and rebellion.

Note that adolescents participate in their own monitoring: Some happily tell everyone about their activities, whereas others are secretive (Vieno et al., 2009). A “dynamic interplay between parent and child behaviors” (Abar et al., 2014, p. 2177) is particularly apparent in adolescence. Most teenagers disclose only part of the truth to their parents, selectively omitting whatever would meet disapproval (Brown & Bakken, 2011).

Thus, monitoring may signify a mutual, close interaction (Kerr et al., 2010). However, monitoring may be harmful when it derives from suspicion. Especially in early adolescence, if adolescents resist telling their parents much of anything, they are more likely to develop problems such as aggression against peers, lawbreaking, and drug abuse (Laird et al., 2013). But lack of communication may be the symptom, not the cause.

If a parent asks “tell me about that party last night,” the adolescent may reply “it was okay” or “nothing happened.” Disclosure may occur, instead, when the parent is tired, busy, or distracted—

THINK CRITICALLY: When do parents forbid an activity they should approve of, or ignore a behavior that should alarm them?

Control can backfire. Adolescents expect adults to exert some control, especially over moral issues. However, overly restrictive and controlling parenting correlates with many problems, including severe depression (Brown & Bakken, 2011). Further, adults may restrict the wrong activity. One researcher laments that parents sometimes refuse to let their children use social media, inadvertently limiting supportive friendship (boyd, 2014).

With Peers

Adolescents rely on peers to help them navigate the physical changes of puberty, the intellectual challenges of high school, and the social changes of leaving childhood. Friendships are important at every stage, but during early adolescence popularity (not just friendship) is especially coveted (LaFontana & Cillessen, 2010).

A CASE TO STUDY

An Ignorant Parent—

Adults are sometimes oblivious to adolescents’ desire for respect from their contemporaries. My own case is presented here.

My oldest daughter wore the same pair of jeans in tenth grade, day after day. She washed them each night by hand and asked me to put them in the dryer early each morning. I did. My husband was bewildered. “Is this some weird female ritual?” he asked. Years later, she explained that she was afraid that if she wore different pants each day, her classmates would think she cared about her clothes and then criticize her choices.

My second daughter, at 16, pierced her ears for the third time. When I asked if this meant she would do drugs, she laughed at my naiveté. I later saw that many of her friends had multiple holes in their earlobes.

At age 15, my third daughter was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease, cancer. My husband and I weighed opinions from four physicians, each explaining treatment that would minimize the risk of death. She had other priorities: “I don’t care what you choose, as long as I keep my hair.” (Now her health is good, and her hair grew back.)

My youngest, in sixth grade, refused to wear her jacket, even in midwinter. I thought the problem may have been egocentric concern for appearance, so I took her shopping and let her buy exactly the jacket she wanted—

not the one I would have chosen. That jacket was almost never worn, despite freezing temperatures. Not until high school did she tell me she did it so that her classmates would think she was tough.

In retrospect, I am amazed that I was unaware of the power of peers.

Sometimes adults conceptualize adolescence as a tug-

Parents and peers are often mutually reinforcing, although many adolescents downplay the influence of their parents and many parents are unaware of the influence of peers, as I was. Only when parents are harsh or neglectful does peer influence reign alone (Brown & Bakken, 2011).

Closeness to parents protects adolescent self-

Helpful friends can be of either gender. Although same-

peer pressure

When people of the same age group encourage particular behavior, dress, and attitude. This is usually considered negative, when peers encourage behavior that is contrary to norms or morals, but can also be positive.

PEER PRESSURE Adults worry about peer pressure; that is, they fear that peers will push innocent children to use drugs, break laws, and so on. But peers can be more helpful than harmful, especially in early adolescence, if biological and social stresses are overwhelming. Some adolescents are more influenced by peers than others, because genes and early experiences differ (Prinstein et al., 2011; Choukas-

Question 10.11

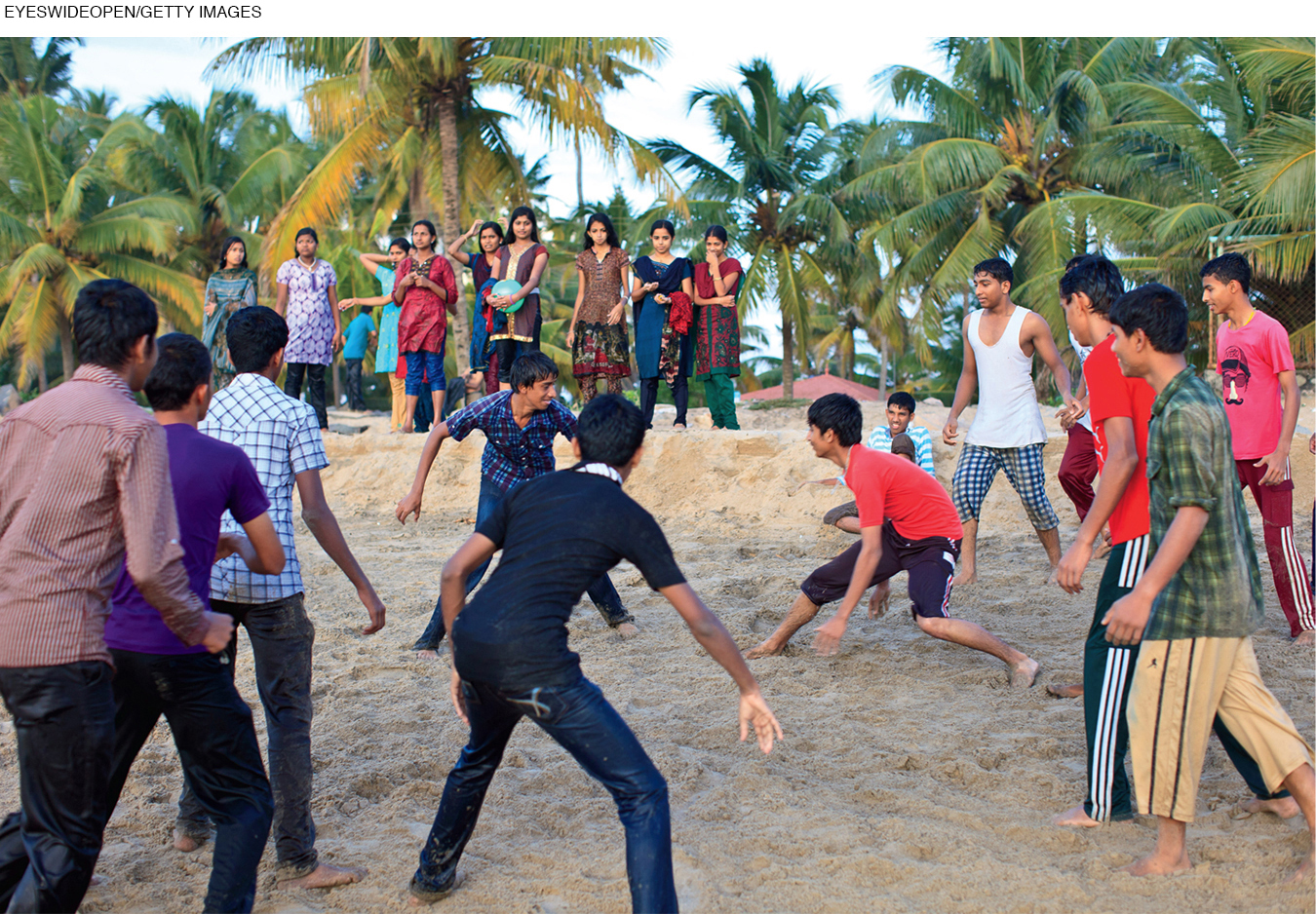

OBSERVATION QUIZ

What evidence do you see that traditional norms remain in this culture?

The girls are only observers, keeping a respectful distance.

Peers are particularly needed by adolescents of minority and immigrant groups as they strive to achieve ethnic identity, attaining their own firm self-

The larger society may promulgate stereotypes and prejudice, and that may make teenagers depressed. Ideally, parents combat that with racial socialization, describing ethnic heroes and reasons to be proud (Umana-

For example, a study of Hispanic adolescents found that, compared to those who did not notice discrimination, those who experienced ethnic prejudice were more likely to abuse drugs. However, their risk of drug abuse was reduced if they proudly identified as Hispanic (Grigsby et al., 2014).

The particular peers who are most influential are those with the adolescent at the moment. This was found in a study in which all the eleventh-

The two versions were:

Your decision to sign up for the course will be kept completely private from everyone, except the other students in the room.

or:

Your decision to sign up for the course will be kept completely private from everyone, including the other students in the room.

A marked difference was found if students thought their classmates would learn of their decision, with the honors students more likely to sign up and the non-

When the decisions of these 107 were said to be unknown to classmates, acceptance rates were similar (72 and 79 percent) no matter which class they were in at the moment of the sign up. But if they thought their classmates might know their decision, imagined peer pressure affected them. For those students who were enrolled in two honors classes and several non-

SOCIAL NETWORKING You read in Chapter 9 about the dangers of technology. Remember, however, that technology is a tool. It might exacerbate depression or self-

Indeed, technology usually brings friends together in adolescence (Mesch & Talmud, 2010). This is obvious with texting, instant messaging, and social media, but it also occurs with video games. Many games now pit one player against another or require cooperation among several players (Collins & Freeman, 2013). Technology users, including video game players, are usually at least as extraverted and socially connected as other adolescents.

Although most social networking is between friends who know each other well, the Internet may be a lifeline for teenagers who are isolated because of their sexual orientation, culture, religion, or home language. These teenagers are vulnerable to depression; technology can help.

Technology may also be vital for adolescents with special health needs. During these years, many refuse to follow special diets, take medication, see doctors, do exercises, or whatever. However, among teenagers with diabetes, some monitor their insulin via smart phone, talk to the doctor via Skype, and chat with other young people with diabetes via the Internet (Harris et al., 2012).

deviancy training

Destructive peer support in which one person shows another how to rebel against authority or social norms.

SELECTING FRIENDS Of course, peers can lead one another into trouble. Collectively, they may provide deviancy training, when one person shows another how to resist social norms (Dishion et al., 2001).

The same phenomenon occurs for many destructive behaviors. A study found that the suicide of a peer, of an admired celebrity, or of a family member, markedly increased the risk of adolescent suicide (Abrutyn & Mueller, 2014).

Especially during adolescence, the actions of other people are contagious. However, innocent teens are not corrupted by deviant peers. Adolescents choose their friends and models—

A developmental progression can be traced: The combination of “problem behavior, school marginalization, and low academic performance” at age 11 leads to gang involvement two years later, deviancy training two years after that, and violent behavior at age 18 or 19 (Dishion et al., 2010, p. 603). This cascade is not inevitable; adults need to engage marginalized 11-

To further understand the impact of peers, two concepts are helpful: selection and facilitation. Teenagers select friends whose values and interests they share, abandoning former friends who follow other paths. Then friends facilitate destructive or constructive behaviors. It is easier to do wrong (“Let’s all skip school on Friday”) or right (“Let’s study together for the chem exam”) with friends. Peer facilitation helps adolescents do things with friends that they might not do alone.

Thus, adolescents select and facilitate, choose and are chosen. Happy, energetic, and successful teens have close friends who themselves are high achievers, with no major emotional problems. The opposite also holds: Those who are drug users, sexually active, and alienated from school choose compatible friends.

A study of identical twins from ages 14 to 17 found that selection typically precedes facilitation, rather than the other way around. Those who later rebelled chose more lawbreaking friends at age 14 compared to their more conventional twin (Burt et al., 2009).

THINK CRITICALLY: Why is peer pressure thought to be much more sinister than it actually is?

Research on teenage cigarette smoking also found that selection precedes peer pressure (Kiuru et al., 2010). Another study found that young adolescents tend to select peers who drink alcohol and then start drinking themselves (Osgood et al., 2013). Finally, a third study, of teenage sexual activity, again found that peer selection was crucial (van de Bongardt et al., 2014). Thus, peers provide opportunity, companions, and encouragement for what adolescents are inclined to do.

With Romantic Partners

A half-

Groups of friends, exclusively one sex or the other

A loose association of girls and boys, with public interactions within a crowd

Small mixed-

sex groups of the advanced members of the crowd Formation of couples, with private intimacies

Culture affects the timing and manifestation of each step on Dunphy’s list, but subsequent research in many nations validates the sequence. Heterosexual youths worldwide (and even the young of other primates) avoid the other sex in childhood and are attracted to them by adulthood. Biology underlies this universal sequence, but the specific types of interaction—

The peer group is part of the process. Romantic partners, especially in early adolescence, are selected not for their individual traits as much as for the traits that peers admire. If the leader of a girls’ group pairs with the leader of a boys’ group, the unattached members of the two cliques tend to pair off as well.

A classic example is football players and cheerleaders: They often socialize together and then pair off with someone from the other group. Which particular football player or cheerleader is chosen depends more on availability than compatibility, which helps explain why adolescent romantic partners tend to have less in common, in personality and attitudes, than adult couples do (Zimmer-

Video: Romantic Relationships in Adolescence explores teens’ attitudes and assumptions about romance and sexuality.

FIRST LOVE Teens’ first romances typically occur in high school, with girls having a steady partner more often than boys do. Exclusive commitment is the ideal, but it is hard to maintain: “cheating,” flirting, switching, and disloyalty are rife. Breakups are common, as are unreciprocated crushes.

All teen romances are fraught with complications, and emotions zigzag from exhilaration to despair, leading to revenge or depression. In such cases, peer support can be a lifesaver; friends help adolescents cope with romantic ups and downs (Mehta & Strough, 2009).

Check out the Data Connections activity Sexual Behaviors of U.S. High School Students, which examines how sexually active teens really are.

For adults, satisfaction with a romantic relationship is a powerful antidote to depression. However, teen romances are unlike adult ones. One study of 60 adolescent couples found that “Contrary to expectation, relationship break-

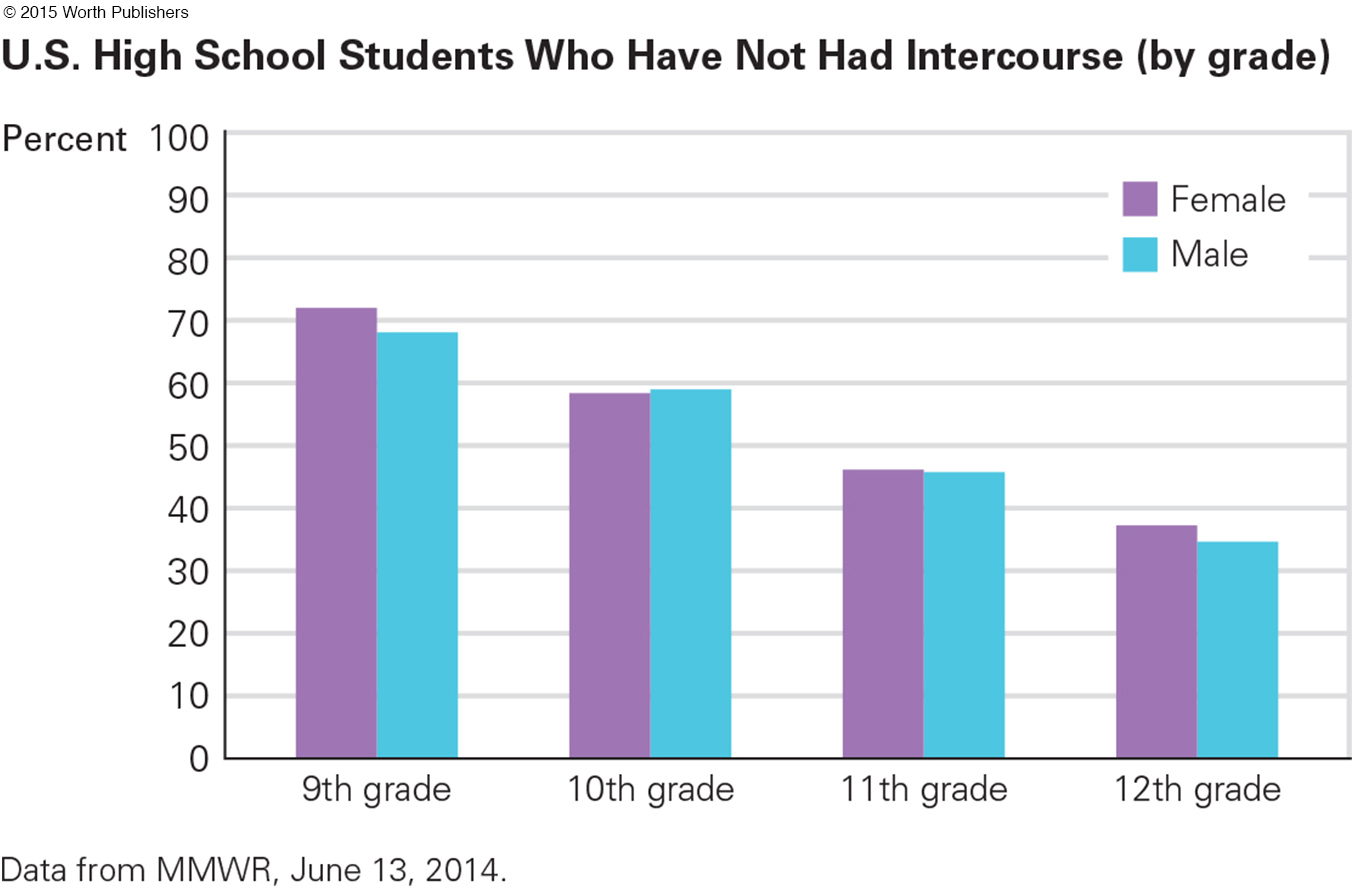

Many teenage romances do not include coitus. In the United States in 2013, even though more than one-

For instance, more than twice as many high school students in Memphis than in San Francisco say they have had intercourse (60 percent versus 26 percent) (MMWR, June 13, 2014). Within every city are many subgroups, each with its own norms.

Parents have an impact. Thus, when parent–

sexual orientation

A person’s sexual and romantic attraction to others of the same sex, the other sex, or both sexes.

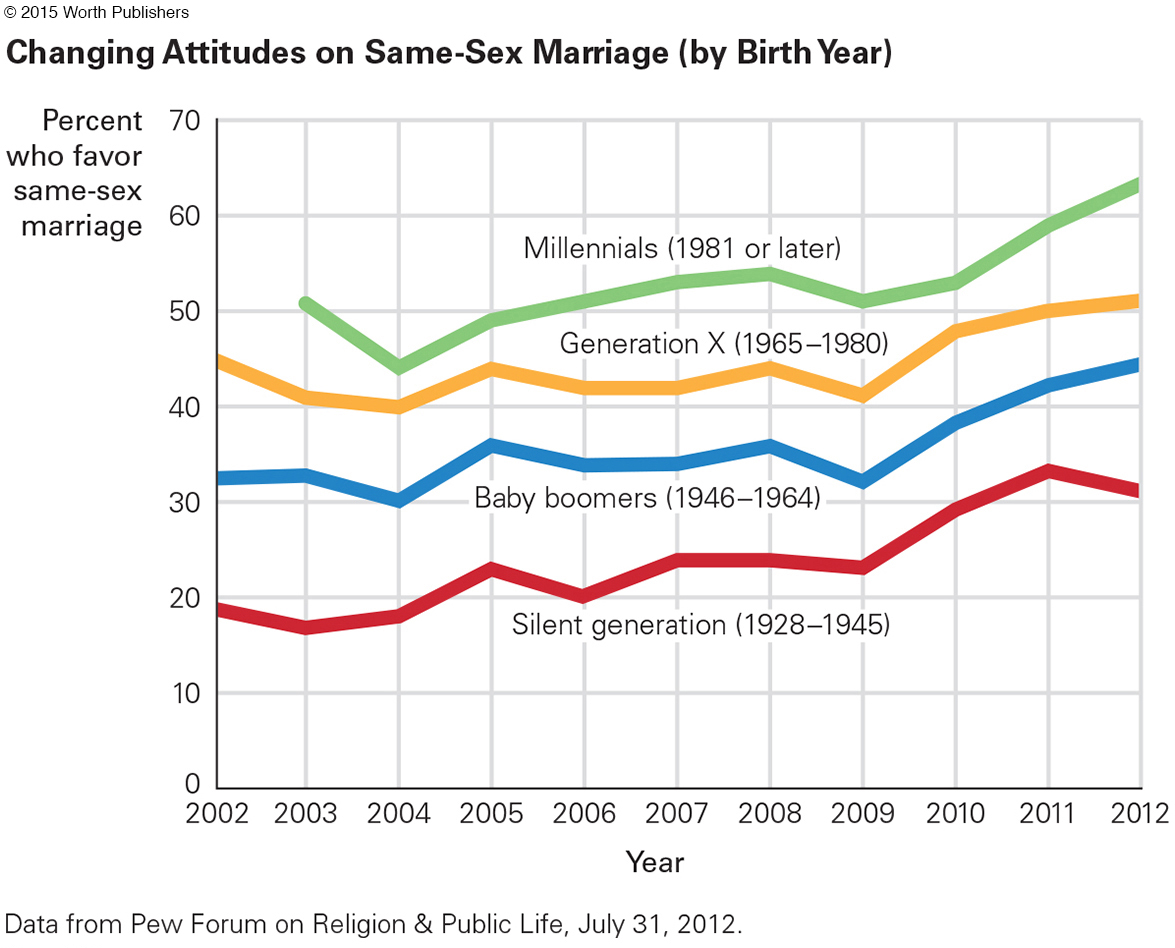

SAME-

Obviously, culture and cohort are powerful. Some cultures accept youth who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender (the census in India asks people to identify as male, female, or Hijra [transgender]). Other cultures criminalize them (as do 38 of the 53 African nations), sometimes even killing them (Uganda).

Worldwide, many gay youths date members of the other sex to hide their orientation; deception puts them at risk for binge drinking, suicidal thoughts, and drug use. Those hazards are less common in cultures where same-

At least in the United States, adolescents have similar difficulties and strengths whether they are gay or straight (Saewyc, 2011). However, lesbian, gay, transsexual, and bisexual youth are at greater risk of depression and anxiety, for reasons from every level of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological approach (Mustanski et al., 2014).

Sexual orientation is surprisingly fluid during the teen years. Girls often recognize their orientation only after their first sexual experiences; many adult lesbians had other-

sexually transmitted infection (STI)

An infection spread by sexual contact; includes syphilis, gonorrhea, genital herpes, chlamydia, and HIV.

In one detailed study, 10 percent of sexually active teenagers had had same-

SEX EDUCATION Many adolescents have strong sexual urges but minimal logic about pregnancy and disease, as might be expected from the ten-

As a result, “students seem to waffle their way through sexually relevant encounters driven both by the allure of reward and the fear of negative consequences” (Wagner, 2011, p. 193). They have much to learn. Where do they learn it?

Many adolescents learn about sex from the media. The Internet is a common source. Unfortunately, Web sites are often frightening (featuring pictures of diseased sexual organs) or mesmerizing (containing pornography), and young adolescents are particularly naive. Further, adolescents tend to focus on what is funny or odd, not on what is accurate, because, as one young man explained, “no one wants to get a lecture whilst they are online and trying to be doing their social thing” (quoted in Evers et al., 2013, p. 269).

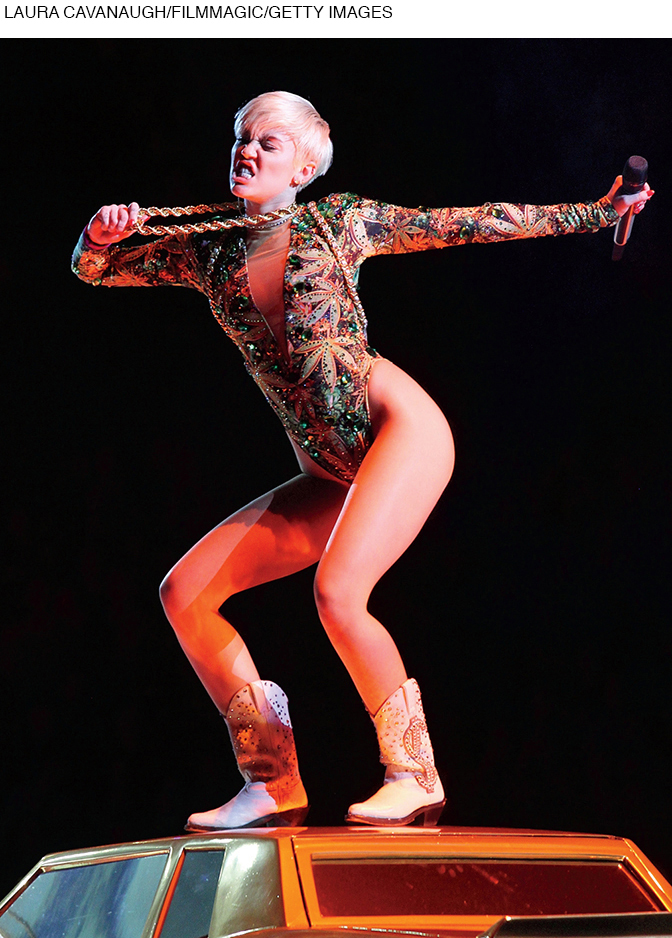

Media consumption peaks at puberty. The TV shows most watched by teenagers include sexual content almost seven times per hour (Steinberg & Monahan, 2011). That content is alluring: Almost never does a television character develop an STI, deal with an unwanted pregnancy, or mention (much less use) a condom.

Music and magazines may be worse. One study found that men’s magazines convince teenage boys that maleness means sexual conquests (Ward et al., 2011).

Adolescents with intense exposure to sexual content on the screen and in music are more often sexually active, but the direction of this correlation is controversial. Are teenagers drawn to sexy images because they are sexually active, or does the media cause them to be sexually involved? One analysis concludes that “the most important influences on adolescents’ sexual behavior may be closer to home than to Hollywood” (Sternberg & Monahan, 2011, p. 575).

As that quote implies, sex education begins within the family. Every study finds that parental communication influences adolescents’ behavior, and many programs of sex education explicitly require parental participation (Silk & Romero, 2014; J. Grossman et al., 2014). However, some parents wait too long and are uninformed about current STIs and contraception.

Parents often express clichés and generalities, unaware of their adolescents’ sexuality, and adolescents conclude that parents know nothing about sex. Embarrassment, silence, and ignorance are common. An attempt to combat that is a program of sex education for parents of adolescents, which increased conversation as well as information (Colarossi et al., 2014).

It is not unusual for parents to think their own child is not sexually active while fearing that the child’s social connections are far too sexual (Elliott, 2012). One study makes the point: Parents of 12-

The Data Connections activity Major Sexually Transmitted Infections: Some Basics offers more information about the causes, symptoms, and rates of various STIs.

What should parents say? That is the wrong question, according to a longitudinal study of thousands of adolescents. Teens who were most likely to risk an STI had parents who warned them to stay away from sex.

In contrast, adolescents were more likely to remain virgins if their relationship with their parents was good. Specific information was less important than open communication (Deptula et al., 2010). Parents should not avoid talking about sex, but honest conversation provides better protection than specifics (Hicks et al., 2013).

Especially when parents are silent, forbidding, or vague, adolescent sexual behavior is strongly influenced by peers. Boys learn about sex from other boys (Henry et al., 2012), girls from other girls, with the strongest influence being what peers say they have done, not something abstract or moral (Choukas-

Partners also teach each other. However, their lessons are more about pleasure than consequences: Most U.S. adolescent couples do not decide together before they have sex how they will prevent pregnancy and disease, and what they will do if their prevention efforts fail. Adolescents were asked with whom they discussed sexual issues. Friends were the most common confidants, then parents, and last of all dating partners. Indeed, only half of them had ever discussed anything about sex with their romantic partner (Widman et al., 2014).

Most parents of pre-

Teachers in most northern European middle schools discuss masturbation, same-

Rates of teenage pregnancy in European nations are less than half those in the United States. Perhaps curriculum is the reason, although schools are affected by society, and cultural differences regarding sexual values and behavior are vast. Nonetheless, in non-

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Sex Education in School

Within the United States, the timing and content of sex education vary by state and community. Among the variations:

Some middle and high schools provide comprehensive education, free condoms, and medical treatment; others provide nothing.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, in 2013, recommended condom distribution in school, but many school board members disagree.

Some schools begin sex education in the sixth grade; others wait until senior year of high school.

Some middle school sex-

education programs successfully increase condom use and delay sexual activity, but other programs have no apparent impact

[Hamilton et al., 2013; Kirby & Laris, 2009]

One controversy has been whether sexual abstinence should be taught as the only acceptable strategy. Of course, abstaining from sex (including oral and anal sex) prevents STIs and pregnancy, but longitudinal data on abstinence-

In that research, students in the abstinence group were found to know slightly less about preventing disease and pregnancy, but every measured sexual activity was similar in both groups. A more recent meta-

A developmental concern is that for the past thirty years adolescents in the United States have more STIs and unwanted pregnancies than adolescents in other developed nations. In some European nations, sex education is part of the curriculum even before puberty, although politics sometimes clash with comprehensive, early sex education in every nation (Parker et al., 2009).

The problem may be that sex education does not consider what we know about adolescent thinking and psychology. Teachers present morals and facts, but teens respond to customs, impulses, and emotions. Sexual behavior does not spring from the prefrontal cortex but from deep within the brain. Knowing how and why to use a condom does not guarantee a wise choice when passions run high and the pain of social rejection looms.

Consequently, effective sex education must engage emotions more than logic, and it must include role-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 10.12

1. How does the influence of peers and parents differ for adolescents?

Disputes between parents and adolescents are common because the adolescent’s drive for independence, arising from biological as well as psychological impulses, clashes with the parents’ desire to maintain control. Adolescents rely on peers to help them navigate the physical changes of puberty, the intellectual challenges of high school, and the social changes of leaving childhood. For every adolescent, peer opinions and friends are vital. Adults sometimes fear peer pressure; that is, they fear that peers will push an adolescent to use drugs, break the law, or do other things their child would never do alone. But peers are more helpful than harmful, especially in early adolescence, when biological and social stresses can be overwhelming. Each young person must fashion his or her own identity, distinct from that of either society or parents. For this, peers may be pivotal.

Question 10.13

2. When, and about what, are parents and adolescents most likely to argue?

Adolescents are establishing their independence and asserting their autonomy while parents still want to maintain some control over their adolescents’ lives. Each generation misjudges the other: Parents think their offspring resent them more than they actually do, and adolescents imagine their parents want to dominate them more than they actually do. Unspoken concerns need to be aired so both generations better understand each other. Some bickering may indicate a healthy family, since close relationships almost always include conflict.

Question 10.14

3. When is parental monitoring of adolescent activity beneficial and when is it not helpful?

When parental monitoring grows out of a warm, supportive relationship, children are likely to become confident, well-

Question 10.15

4. Why do many adults misunderstand the role of peer pressure?

Sometimes adults conceptualize adolescence as a time when peers and parents are at odds, or worse, as a time when peer influence overtakes parental influence. However, healthy communication and support from parents make constructive peer relationships more likely.

Question 10.16

5. How do parents and society affect an adolescent’s development of ethnic identity?

Peers may be particularly helpful for adolescents of minority and immigrant groups as they strive to achieve ethnic identity, attaining their own firm (not confused or foreclosed) understanding of what it means to be their ethnicity. The larger society provides stereotypes and prejudice, and parents ideally describe ethnic heroes and reasons to be proud.

Question 10.17

6. How do friends help adolescents?

Teenagers select friends whose values and interests they share, abandoning former friends who follow other paths. Then friends facilitate destructive or constructive behaviors. It is easier to do wrong or right with friends. Peer facilitation helps adolescents act in ways they are unlikely to act on their own. Adults are not as susceptible to peer facilitation.

Question 10.18

7. How do adolescents choose romantic partners?

Adolescents select romantic partners based on traits that their peers admire, which helps explain why adolescent couples tend to have less in common than adult couples.

Question 10.19

8. How does culture affect sexual orientation?

Culture determines the norms and standards associated with sexual orientation. Adolescents are aware of these norms and standards, which can influence the acceptance and expression of their own sexual orientation. Worldwide, many gay youths date members of the other sex to hide their orientation, and they are at higher risk for binge-

Question 10.20

9. From whom do adolescents usually learn about sex?

Adolescents learn about sex from the media, their peers, and their families, as well as their religious institutions. They also receive instruction from teachers at school.

Question 10.21

10. What are national variations in sex education in schools?

Some high schools provide comprehensive education, free condoms, and medical treatment; some teach abstinence as the only sexual strategy for adolescents; others provide nothing. If they begin early, many sex-