Drug Use and Abuse

Hormonal surges, the brain’s reward centers, and cognitive immaturity make adolescents particularly attracted to the sensations produced by psychoactive drugs. But their immature bodies and brains make drug use especially hazardous.

Variations in Drug Use

Video: Risk-

Most teenagers try psychoactive drugs, that is, drugs that activate the brain. Cigarettes, alcohol, and many prescription medicines are as addictive and damaging as illegal psychoactive drugs such as cocaine and heroin. Further, many new “designer drugs” hit the market every month. Merely keeping track of them is difficult: The United States Institute of Drug Abuse analyzed the chemical structure of 300 such drugs in the past decade, finding some (e.g., “bath salts”) highly addictive and dangerous to the brain (Underwood, 2015).

AGE TRENDS For many developmental reasons, adolescence is a sensitive time for experimentation, daily use, and eventual addiction (Schulenberg et al., 2014). Both prevalence and incidence of drug use increase from about age 10 to age 25 and then decrease, as adult responsibilities and experiences make drugs less attractive. Most worrisome is drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes before age 15, because early use escalates. That makes depression, sexual abuse, bullying, and later addiction more likely (Merikangas & McClaire, 2012; Mennis & Mason, 2012).

Although drug use increases as adolescents mature, there is one tragic exception: inhalants (fumes from aerosol containers, glue, cleaning fluid, etc.). Sadly, the youngest adolescents are most likely to try inhalants, because they find them easy to get and they are least able, cognitively, to understand the risk of one-

VARIATIONS BY PLACE, GENERATION, AND GENDER Nations vary markedly. Consider the most common drugs: alcohol and tobacco.

In most European nations, beer or wine is part of every dinner, and children as well as adults partake. The opposite is true in much of the Middle East, where alcohol is illegal as well as forbidden for Muslims. Consequently, teenagers almost never taste it. The only alcohol available is concocted illegally and is dangerous—

Cigarettes are available everywhere, but again national differences are dramatic. In many Asian nations, anyone anywhere may smoke; in the United States, adolescents are forbidden to buy or smoke tobacco, and in many private and public places smoking by anyone of any age is prohibited. Nonetheless, 48 percent of U.S. high school seniors have tried smoking (MMWR, June 13, 2014). In Canada, cigarette advertising is outlawed, and cigarette packs have graphic pictures of diseased lungs, rotting teeth, and so on. Fewer Canadian than U.S. teenagers smoke.

Variations within nations are also marked. In the United States, three-

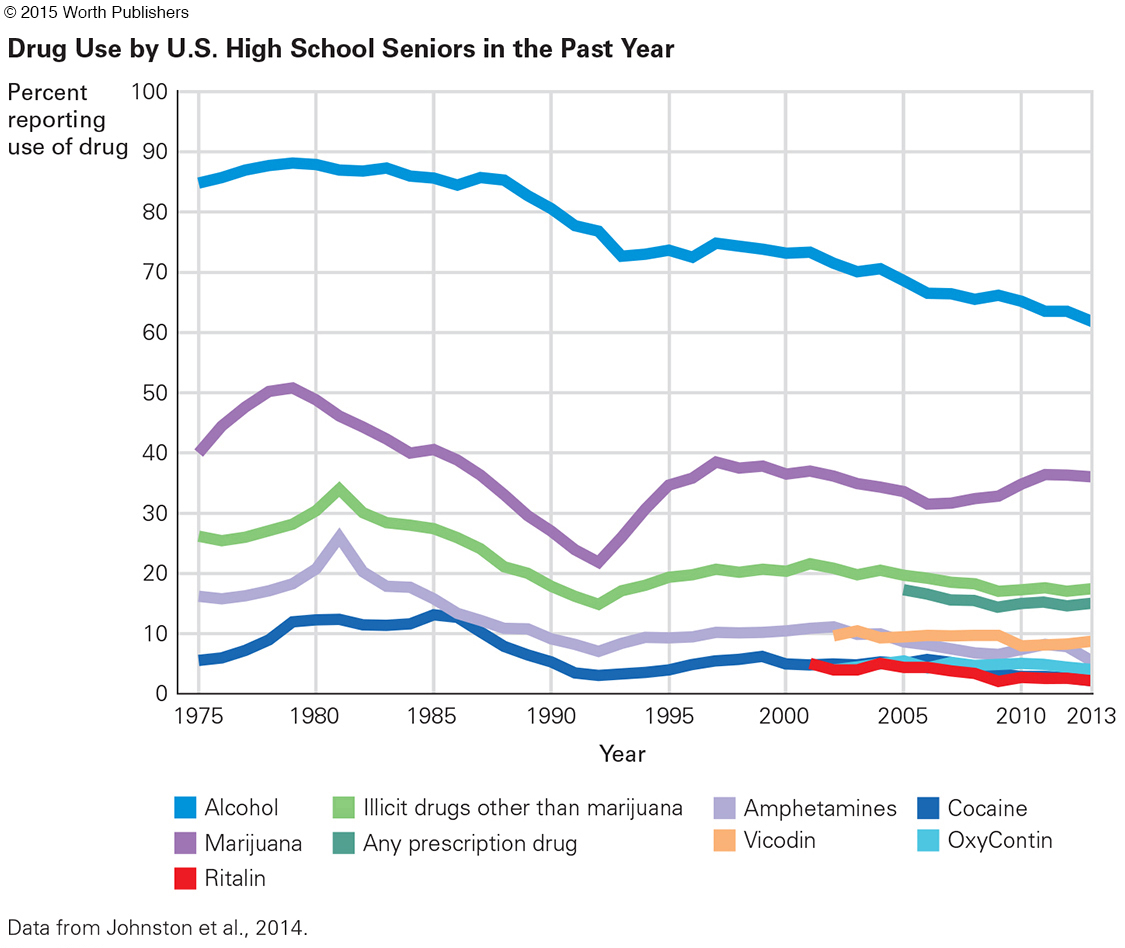

Cohort differences are evident as well, even over a few years. Use of most drugs has decreased in the United States since 1976 (see Figure 10.5), with the most notable decreases in marijuana and the most recent decreases in synthetic narcotics and prescription drugs (Johnston et al., 2014). Vaping (using e-

Not only are data not yet known, but philosophy differs, from those who believe drug use is inevitable and therefore e-

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

E-

Controversial is the use of e-

If e-

However, will adolescents who try e-

Empirical data from one research study are chilling: Among adolescents, three times as many smoked e-

A victory for North American public health has been a marked reduction in regular cigarette smoking. Not only are there only half as many adult smokers as there were in 1950, adolescent smoking has markedly declined and smoking is forbidden in many public places.

In most private homes as well, smoking is not allowed. In 2010 in the United States, such homes are the majority (83 percent), an increase from less than 1 percent in 1970 and 43 percent in 1992. Most of those homes have no smokers, but cigarettes are banned in 46 percent of the homes where a smoker lives (MMWR, September 5, 2014).

That is clearly a victory to celebrate. Although e-

The opposing perspective is that e-

Longitudinal data show that the availability of drugs does not have much impact on use: Most high school students say they could easily get alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana if they wish. However, perception of risks varies by cohort, and that has a large effect on use.

With some exceptions, adolescent boys use more drugs, and use them more often, than girls do, especially outside the United States (Mennis & Mason, 2012). In Asia and South America, about four times as many boys as girls smoke. Although the exact proportion varies by nation, almost everywhere girls smoke less than boys (Giovino et al., 2012).

These gender differences are reinforced by social constructions about proper male and female behavior. In Indonesia, for instance, 38 percent of the boys smoke cigarettes, but only 5 percent of the girls do. One Indonesian boy explained, “If I don’t smoke, I’m not a real man” (quoted in Ng et al., 2007).

Gender differences among U.S. teenagers have diminished in recent years. Females smoke cigarettes about as often as males (19 percent of the senior girls and 20 percent of the senior boys smoked in the past year), but girls drink alcohol at younger ages (MMWR, June 13, 2014), perhaps because they reach puberty sooner. Body image is important for adolescents of both sexes; consequently boys use more steroids and girls use more diet drugs.

Harm from Drugs

Many researchers find that drug use before maturity is particularly likely to harm body and brain growth. However, adolescents typically deny that they experience any harm or could ever become addicted. Few adolescents notice when they or their friends move past use (experimenting) to abuse (experiencing harm) and then to addiction (needing the drug to avoid feeling nervous, anxious, sick, or in pain).

A related problem is the adolescent brain, more activated by sensation-

A major problem is that adolescents assume that some drugs are harmless, especially ones that are prescribed by a doctor, or purchased legally. They are slow to realize that cigarettes, alcohol, prescription drugs, and “energy” drinks can be addictive and even fatal (Meier, 2012).

TOBACCO, ALCOHOL, AND MARIJUANA Each drug is harmful in a particular way. An obvious negative effect of tobacco is that it impairs digestion and nutrition, slowing down growth. This is true not only for cigarettes but also for bidis, cigars, pipes, and chewing tobacco, and probably e-

Since internal organs continue to mature after the height spurt, drug-

Youth are particularly vulnerable to alcohol abuse, because the regions of the brain that are connected to pleasure are more strongly affected by alcohol during adolescence than at later ages. That makes teenagers less conscious of the “intoxicating, aversive, and sedative effects” of alcohol (Spear, 2013, p. 155). Brain damage by alcohol during adolescence has been proven with controlled research on mice, with the results seeming to extend to humans as well.

Marijuana seems harmless to many people (especially teenagers), partly because users seem more relaxed than impaired. Yet adolescents who regularly smoke marijuana are more likely to drop out of school, become teenage parents, be depressed, and later be unemployed. Marijuana affects memory, language proficiency, and motivation—

Many developmentalists fear that more acceptance of marijuana among adults will lead to less learning and poorer health among teenagers. Marijuana is often the drug of choice among wealthier adolescents, who then become less motivated to achieve in school and more likely to develop other problems (Ansary & Luthar, 2009). It seems as if, rather than lack of ambition leading to marijuana use, marijuana destroys ambition.

Several states in the United States have legalized marijuana, increasingly for recreational, not merely medical, use. The law everywhere forbids marijuana, as well as cigarettes and alcohol, for teenagers, because of the aforementioned harm to adolescent bodies and brains. It remains to be seen whether adolescents will access marijuana as readily as they do alcohol, and if this is as harmful as some fear.

CORRELATION AND CAUSE Some researchers wonder whether these are correlations, not causes. It is true that depressed and abused adolescents are more likely to use drugs, and that later these same people are likely to be more depressed and further abused. Maybe the stresses of adolescence lead to drug use, not vice versa.

However, longitudinal research suggests that drug use causes more problems than it solves, often preceding anxiety disorders, depression, and rebellion (Maslowsky et al., 2014). Further, adolescents who use alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana recreationally as teenagers are more likely to abuse these and other drugs after age 20 (Moss et al., 2014). That may be true for e-

Longitudinal studies of twins (which allow control for genetics and family influences) find that, although many problems predate drug use, drugs themselves add to the problems (Lynskey et al., 2012; Korhonen et al., 2012). Most adolescents covet the drugs that slightly older youth use, and many 18-

THINK CRITICALLY: Might the fear of adolescent drug use be foolish, if most adolescents use drugs whether or not they are forbidden?

In 1999 New Zealand lowered the age for legal purchase of alcohol from 20 to 18. One result: an uptick in hospital admission for intoxication, car crashes, and injuries from assault in 16-

Preventing Drug Abuse: What Works?

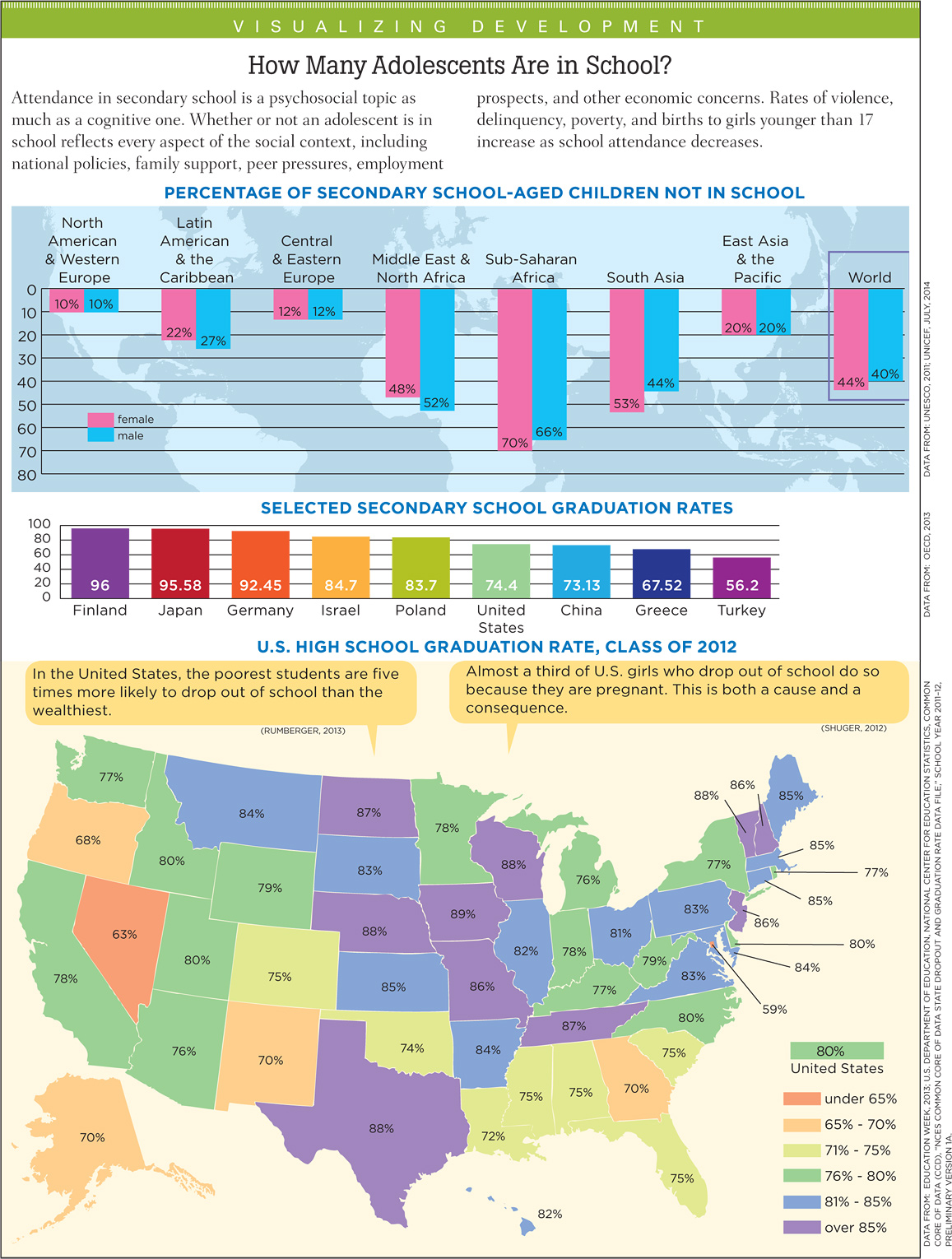

Drug abuse is progressive, beginning with a social interaction and ending alone. The first use usually occurs with friends; occasional use is a common expression of friendship or generational solidarity. An early sign of trouble is a drop in school grades, but few notice that as early as they should (see Visualizing Development, p. 382).

However, the Monitoring the Future study found that among high school seniors in 2013:

22 percent had five drinks in a row in the past two weeks.

9 percent smoked cigarettes every day for the past month.

6.5 percent smoked marijuana every day.

[Johnston et al., 2014]

These figures are ominous, suggesting that addiction is the next step. Another problem is synthetic marijuana (“spice,” not widely available until 2009), which was used by 11 percent of high school seniors in 2012 (Johnston et al., 2014), and e-

Remember that most adolescents think they are exceptions, sometimes feeling invincible, sometimes extremely fearful of social disapproval, but almost never worried that they themselves will become addicts. They rarely realize that every psychoactive drug excites the limbic system and interferes with the prefrontal cortex.

Because of these neurological reactions, drug users are more emotional (varying from euphoria to terror, from paranoia to rage) than they would otherwise be. They are also less reflective. Moodiness and impulsivity are characteristic of adolescents, and drugs make them worse. Every hazard—

generational forgetting

The idea that each new generation forgets what the previous generation learned.

With harmful drugs, as with many aspects of life, each generation prefers to learn things for themselves. A common phenomenon is generational forgetting, that each new generation forgets what the previous generation learned (Chassin et al., 2014; Johnston et al., 2012).

Mistrust of the older generation, and loyalty to peers, leads not only to generational forgetting but also to a backlash against prohibitions. If something is forbidden, that is a reason to try it, especially if adults exaggerate the dangers of drugs. If a friend passes out from drug use, adolescents hesitate to get medical help because that would be an admission that the drug was harmful.

Some antidrug curricula and advertisements actually make drugs seem exciting. Antismoking announcements produced by cigarette companies (such as a clean-

This does not mean that trying to halt early drug use is hopeless. Massive ad campaigns by public health advocates in Florida and California cut adolescent smoking almost in half, in part because the publicity appealed to the young. Public health advocates have learned that teenagers respond to graphic images. In one example:

A young man walks up to a convenience store counter and asks for a pack of cigarettes. He throws some money on the counter, but the cashier says “That’s not enough.” So the young man pulls out a pair of pliers, wrenches out one of his teeth and hands it over. . . . a voiceover asks: “What’s a pack of smokes cost? Your teeth.”

[Krisberg, 2014]

Parental example and social changes also make a difference. Throughout the United States, higher prices, targeted warnings, and better law enforcement have led to a marked decline in cigarette smoking among younger adolescents. In 2012, only 5 percent of eighth-

Looking broadly at the past two chapters and the past 40 years in the United States, we see that universal biological processes do not lead to universal psychosocial problems. Sharply declining rates of teenage births and abortions, increasing numbers graduating from high school, and less misuse of legal drugs are apparent in many nations. Adolescence starts with puberty; that much is universal. But what happens next depends on parents, peers, schools, communities, and cultures.