Body Development

Biologically, the years from ages 18 to 25 are prime time for hard physical work and safe reproduction. However, the fact that young adults can carry rocks, plow fields, or produce babies is no longer admired.

If a contemporary young couple dropped out of high school to marry and then had a new baby year after year, their neighbors would be appalled, not approving. Societies, families, and young adults themselves expect more education, later marriage, and fewer offspring than the norm a few decades ago.

By this point in your study, the previous paragraph probably raises questions in your mind, because you are well aware of cultural differences in what societies expect. Might some neighbors in some regions of the world approve of a young, fertile couple? As the following Opposing Perspectives suggests, developmentalists also ask this question.

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

A Welcome Stage, or Just WEIRD?

This chapter is about emerging adulthood as a stage of human development, a time for questions, exploration, and experimentation. Careful questioning allows people to choose mates and jobs carefully. But some scholars consider emerging adulthood neither beneficial nor universal. Instead, this new stage may be a cultural phenomenon for privileged youth who can afford to postpone work and family commitments.

The term emerging adulthood was coined by Jeffrey Arnett, a college professor in Missouri who listened to his own students and realized they were neither adolescents nor adults. As a good researcher, he also queried young adults of many backgrounds in other regions of the United States, he read published research about “youth” or “late adolescence,” and he thought about his own life. He decided that a new stage, requiring a new label, had appeared.

Arnett and others have now studied young adults in many Western European nations, and youth there also meet the criteria for emerging adults. For example, when Danish 20-

But some scientists hold an opposing perspective. They are particularly critical of any faculty member at a U.S. university who studies his or her own students and then draws conclusions about all humankind.

Conclusions based on American college students may apply only to those who are WEIRD—

From that perspective, skewed perceptions are apparent. Indeed, referring to “the West” (North America and Western Europe) exposes a bias. Since the earth is round, people in “East Asia” (Japan, Korea, China) should call the United States “the East,” and call the Middle East (Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and so on) “the Midwest.”? Arnett himself contended that too much of developmental science focuses on only 5 percent of humanity (Arnett, 2008).

The Canadian professor who developed the acronym WEIRD wrote, “many psychologists . . . tend to think of cross-

If WEIRD people differ in notable ways from others, that calls into question the stage of emerging adulthood that depicts young adults as autonomous and independent, forging a future untethered by parents, partners, children, or work commitments. A contrasting worldview may be especially apparent in Asia, where social interdependence—

For example, in Thailand youth involvement with parents and community is a bulwark against drug abuse (Wongtongkam et al., 2014). Looking at the data, researchers suggest that Thai youth should be encouraged to stay home until they marry, avoiding the allure of Western independence. Perhaps emerging adulthood is a luxury stage, attained only by U.S. college students.

Some scientists have directly examined the assumption that emerging adulthood is universal. One study of personality development among youth in 62 nations found that this transition time was evident everywhere but also that the age when adulthood began was strongly affected by having a steady job. When work began early (as in Pakistan, Malaysia, and Zimbabwe), personality maturation was rapid; when work began late (as in the Netherlands, Canada, and the United States), emerging adulthood lasted many years (Bleidorn et al., 2013).

Recent research suggests that emerging adulthood is coming to every nation, not just the WEIRD ones. For example, an analysis of Chinese culture over the past 40 years finds that communal values decreased while individual competitiveness increased (Zeng & Greenfield, 2015). Evidence such as this leads most scholars to believe that, although it was first recognized in Missouri, emerging adulthood is now evident worldwide.

Consider statistics on age of first marriage. A century ago, most women married in their teens. Now in sub-

Data on childbearing, college attendance, and career commitment show similar worldwide trends. Perhaps those who do not acknowledge a time between adolescence and adulthood are stuck in the past, when economic pressure meant everyone had to become an adult by age 18.

However, consider a new risk. By bestowing a label on this period, does that imply that it is acceptable or even laudable for young people to experiment and explore in their 20s? Should they refuse to settle down, or is that WEIRD? Is a new opposing perspective needed?

Strong and Active Bodies

Health from ages 18 to 25 is one aspect of development that has not changed, except maybe to improve. As has been true for thousands of years, every body system—

Serious diseases rarely appear, and some childhood ailments are outgrown. As young people with chronic problems such as diabetes develop their identity, their sense of who they are and what they want in life leads some to incorporate good health habits that sustain them lifelong (Schwartz et al., 2013).

EXTRA CAPACITY, EXTRA BURDEN To appreciate emerging adult health, it helps to understand three aspects of body functioning: organ reserve, homeostasis, and allostatic load.

organ reserve

The extra capacity built into each organ, such as the heart and lungs, that allows a person to cope with extraordinary demands and to withstand organ strain.

Organ reserve refers to the extra power that each organ can employ when needed. Organ reserve shrinks each year of adulthood, so by old age, a strain—

In the beginning of adulthood, however, organ reserve allows speedy recovery from physical demands. Emerging adults sometimes exercise too long, stay awake all night, or drink too much alcohol. Usually they recover quickly, unlike older adults who might be affected for days.

homeostasis

The adjustment of all the body’s systems to keep physiological functions in a state of equilibrium, moment by moment. As the body ages, it takes longer for these homeostatic adjustments to occur, so it becomes harder for older bodies to adapt to stress.

Closely related to organ reserve is homeostasis—a balance between various body reactions that keeps every physical function in sync with every other. For example, if the air temperature rises, people sweat, move slowly, and thirst for cold drinks—

The next time you read about a rash of heat-

allostasis

A dynamic body adjustment, related to homeostasis, that over time affects overall physiology. The main difference is that while homeostasis requires an immediate response, allostasis requires longer-

Related to homeostasis is allostasis, a dynamic body adjustment that gradually changes overall physiology. The main difference between homeostasis and allostasis is time: Homeostasis requires an immediate response from body systems, whereas allostasis refers to long-

allostatic load

The stresses of basic body systems that combine to limit overall functioning. Higher allostatic load makes a person more vulnerable to illness.

Allostasis depends on the biological circumstances of every earlier time of life, beginning at conception. The process continues, with early adulthood conditions affecting later life, as evident in a measure called allostatic load. Although organ reserve usually protects emerging adults, the effects accumulate because some of that reserve is spent to maintain health, gradually adding to the burden on overall health.

Because of the protective effects of homeostasis and allostasis, few emerging adults reach the threshold that results in serious illness. However, already by early adulthood, childhood health affects metabolism, weight, lung capacity, and cholesterol. As allostatic load builds, the risk of chronic disease later in life increases.

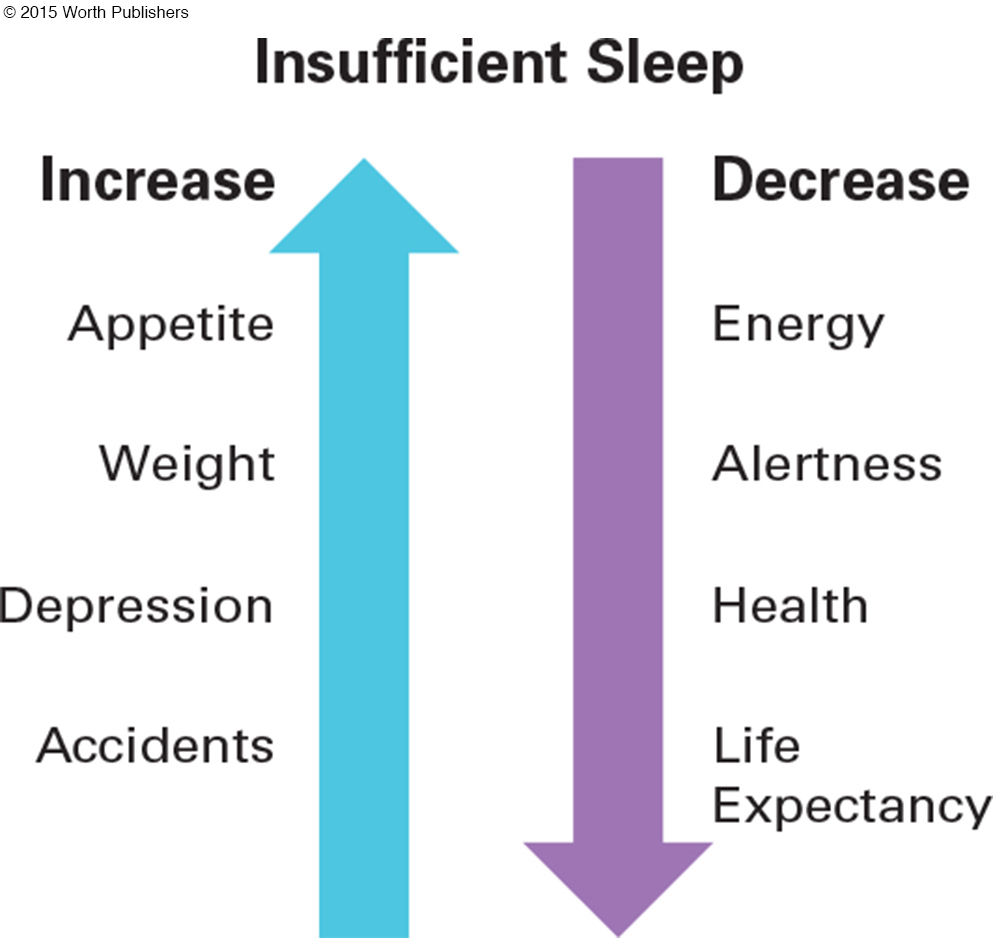

EXAMPLES OF LOAD AND BALANCING Consider sleep. One night’s poor sleep makes a person tired the next day—

Another obvious example is nutrition. If severe malnutrition characterizes fetal or infant development, later on the person might eat too much, becoming obese. Childhood obesity increases the risk of adult obesity—

Of course, appetite is affected by much more than fetal development. How much a person eats on a given day is affected by many factors, as the peripheral nervous system sends messages to the brain. An empty stomach triggers hormones, stomach pains, low blood sugar, and so on, all signaling that it is time to eat. If that is occasional, the cascade of homeostatic reactions makes you suddenly realize at 6 P.M. that you haven’t eaten since breakfast. Dinner becomes a priority; your body tells you that food is needed.

But if a person begins a serious diet, ignoring hunger messages for days and weeks, rapid weight loss soon triggers new homeostatic reactions, allowing the person to function with reduced calorie intake. That makes it harder to lose more weight (Tremblay & Chaput, 2012).

Over the years, allostasis is evident. If a person overeats or starves day after day, the body adjusts: Appetite increases or decreases accordingly. But that ongoing homeostasis increases allostatic load. Obesity is one cause of diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, and so on—

A third example comes from exercise. After a few minutes of exercise, the heart beats faster and breathing becomes heavier—

The opposite is also true, as found in an impressive longitudinal study, CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Adulthood), which began with thousands of healthy 18-

In CARDIA, problems for the least fit began but were unnoticed (except in blood work) when participants were in their 20s. Organ reserve allowed them to function quite well. Nonetheless, each year their allostatic load increased, unless their daily habits changed (Camhi et al., 2013). By age 65, a disproportionate number had died.

These ideas help us understand the long-

FERTILITY, THEN AND NOW As already mentioned, the sexual-

That has changed dramatically. The bodies of emerging adults still crave sex, but their minds know they are not ready for parenthood. Society deems teenage pregnancy a problem, not a blessing. For emerging adults, modern contraception has provided a solution: sex without pregnancy. The world’s 2010 birth rate for 15-

Question 11.1

OBSERVATION QUIZ

One detail in the young man’s hands suggests that the setting is Asia, not North America. What is it?

The cigarette, not the camera. Most young men in Canada and the United States do not smoke, especially publicly and casually, as this man does.

Challenges to Health

Modern medicine has prevented most young-

SEX, NOT MARRIAGE Premarital sex was once forbidden, a taboo enforced with diligent chaperoning, single-

However, effective contraception now allows gratification of sexual impulses without the risk of parenthood. The shotgun wedding “is rapidly becoming a relic” of another era (Jayson, 2014), evidence of a cohort change. When unmarried women today become pregnant, if they continue the pregnancy, less than 10 percent of those in the United States marry before the birth.

Society has adjusted to this new reality in many ways. One example is the demise of the single-

Some feminists contend that, academically, women’s colleges are better, but in terms of protecting women from pregnancy, contraception has replaced segregation. Worldwide, more than 99 percent of college students enroll in co-

NEW DISEASES Fatal diseases are rare during emerging adulthood, and premarital sex without pregnancy seems a good solution to the conflict between physical and psychological maturation. However, that solution creates a new problem.

The rate of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is rising. Organ reserve and medical treatment almost always prevent death in emerging adulthood, but STIs cause infertility and later adult deaths that seem unrelated, such as from cancer and tuberculosis.

Transportation advances have unanticipated consequences. During the same years that contraception improved, travel became far easier and cheaper. In earlier times, prostitution was local, which kept STIs local as well. Now, with globalization, an STI caught in one place quickly spreads. Sex trafficking adds to the problem: Women and girls from one nation who are sent to another sometimes bring infections and sometimes catch diseases they never would have contracted at home.

This proliferation is particularly tragic with HIV/AIDS, which may have existed occasionally and locally for a hundred years. However, within 30 years, primarily because of travel and the sexual activities of young adults, HIV has become a worldwide epidemic, with more female than male victims (Fan et al., 2014).

Young adults are the prime STI vectors (those who spread disease) as well as the most common new victims. Genetic research finds that the subtypes and recombinations of HIV—

Indeed, tracing HIV shows that it originally was confined to one city, Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Then it spread following the route of the railroads built as part of colonial modernization: Carriers took the disease to other nations of Africa, and later to other continents, where it had not been (Faria et al., 2014).

THINK CRITICALLY: What are the benefits and risks of other innovations, such as the cell phone, bypass surgery, frozen food, or air conditioning?

Now jets and bullet trains allow almost every young adult to wander far from home. Travel expands the mind and develops cultural understanding, but it also spreads diseases.

Taking Risks

Remember that each age group has its own gains and losses, characteristics that can be an asset or a liability. This is apparent with risk taking. Some emerging adults bravely, or foolishly, take risks—

In one study, 10-

Risky items were rated more favorably (closer to a good idea) every year from age 10 to 20 and then less favorably (closer to a bad idea) every year from age 20 to 30. Experience increased (the average 15-

The emerging adult’s willingness to take chances sometimes is beneficial. Enrolling in college, moving to a new state or nation, getting married, having a baby—

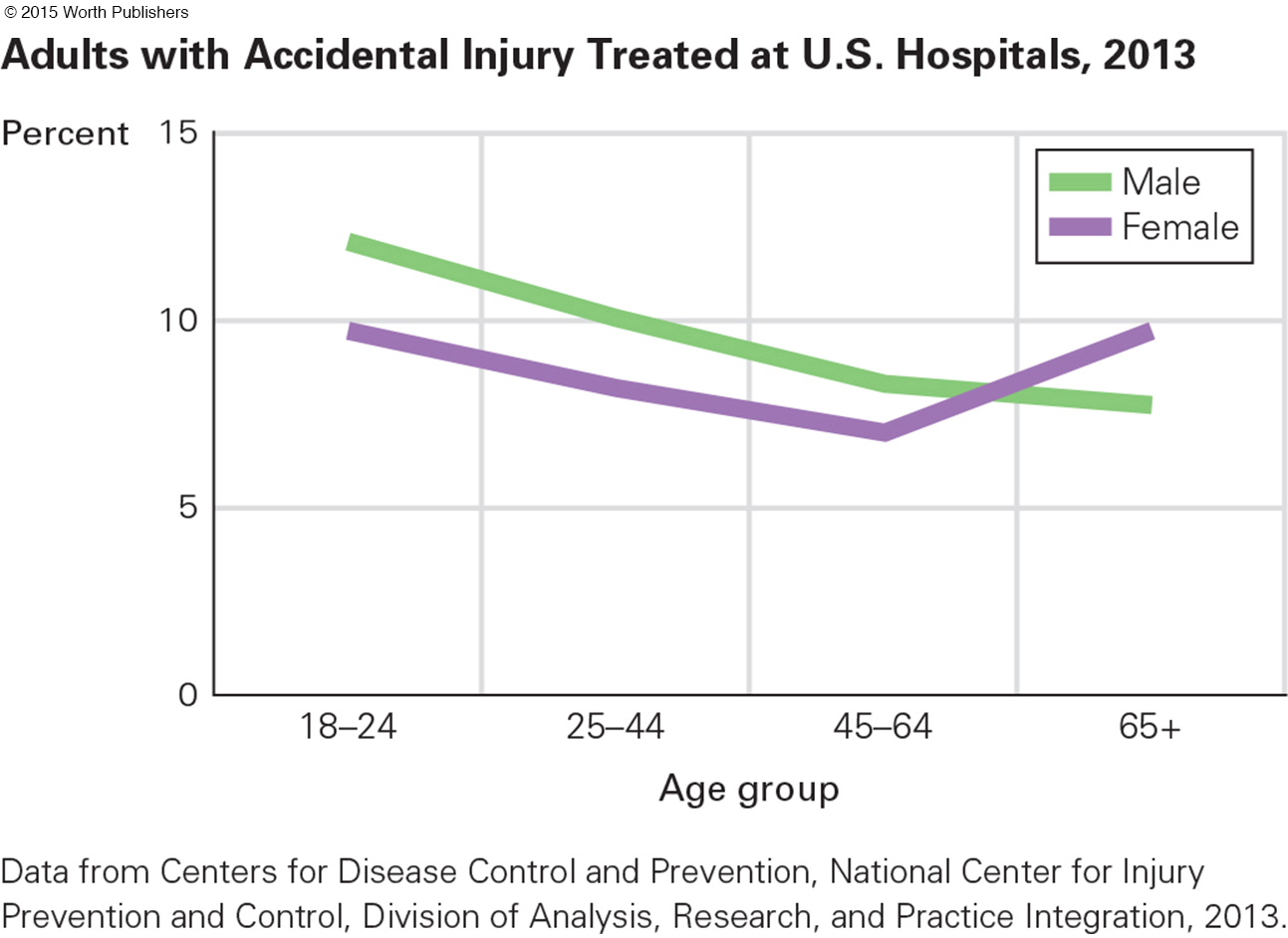

DANGEROUS RISKS However, risk taking is often destructive. Although their bodies are strong and their reactions quick, emerging adults nonetheless have more serious accidents than do people of any other age (see Figure 11.1). The low rate of disease between ages 18 and 25 is counterbalanced by a high rate of violent death.

Risks that are more common in emerging adulthood than any other time include unprotected sex with a new partner, driving without a seat belt, carrying a loaded gun, abusing drugs, and addictive gambling—

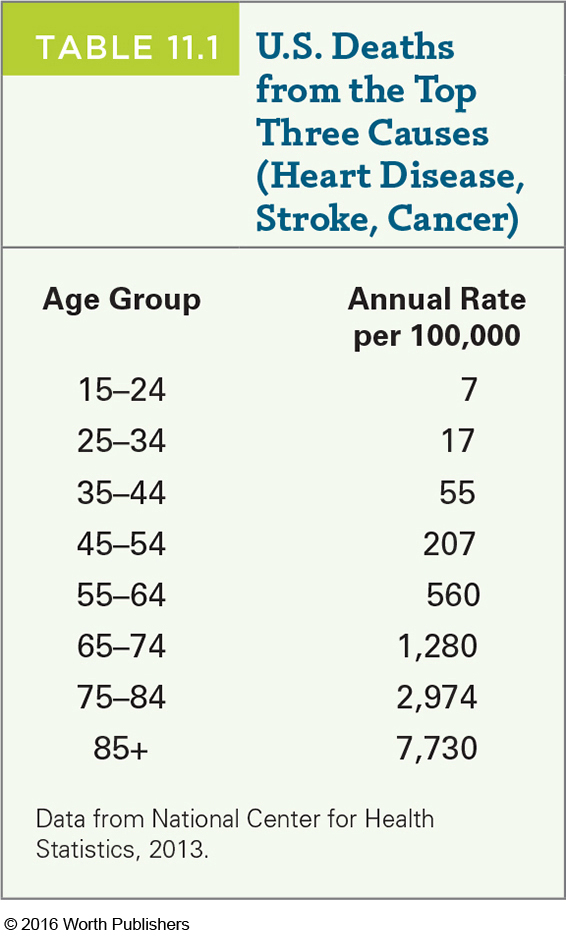

Fatal accidents, homicide, and suicide result in more deaths in emerging adulthood than all other causes combined, even in nations with high rates of infectious diseases and malnutrition. The contrast between sudden, violent deaths and slower, disease-

In the United States, of the 15-

RISKY SPORTS Many young adults enjoy challenging recreation: They climb mountains, swim in oceans, run in pain, play past exhaustion, and so on. This has always been true. Marriage and parenthood slow down risk taking, so when adult responsibilities began earlier, risks were less common. But the impulse to seek danger has always been apparent in young men (think of the soldiers of the previous centuries).

Now recreational risks are more popular, including new ones advertised for hundreds of millions of emerging adults. Among such activities are skydiving, bungee jumping, pond swooping, parkour, potholing (in caves), waterfall kayaking, and ziplining. Serious injury is not the goal, but the possibility adds to the thrill.

extreme sports

Forms of recreation that include apparent risk of injury or death and are attractive and thrilling as a result.

Competitive extreme sports (such as freestyle motocross—motorcycle jumping off a ramp into “big air,” doing tricks during the fall, and hoping to land upright) are new sports for some emerging adults, who find golf, bowling, and so on too tame (Breivik, 2010).

A CASE TO STUDY

An Adrenaline Junkie

The fact that extreme sports are age-

Four years later, Pastrana set a new record for leaping through big air in an automobile, as he drove over the ocean from a ramp on the California shoreline to a barge more than 250 feet out. He crashed into a barrier on the boat but emerged, seemingly ecstatic and unhurt, to the thunderous cheers of thousands of other young adults on the shore (Roberts, 2010).

In 2011, a broken foot and ankle made him temporarily halt extreme sports—

DRUG ABUSE The same impulses that are admired by the young in extreme sports also lead to actions that are clearly destructive, not only for individuals but for the community. The most studied of these are sexual risks and drug abuse.

Both promiscuity and drug use increase in emerging adulthood, which suggests that one might lead to the other. Many colleges now restrict alcohol on campus, believing this will prevent or reduce sexual assault, which tends to occur only when both parties have been drinking or drugging (Zinzow & Thompson, 2015). However, although they often co-

drug abuse

The ingestion of a drug to the extent that it impairs the user’s biological or psychological well-

By definition, drug abuse occurs whenever a drug (legal or illegal, prescribed or not) is used in a harmful way, damaging a person’s physical, cognitive, or psychosocial well-

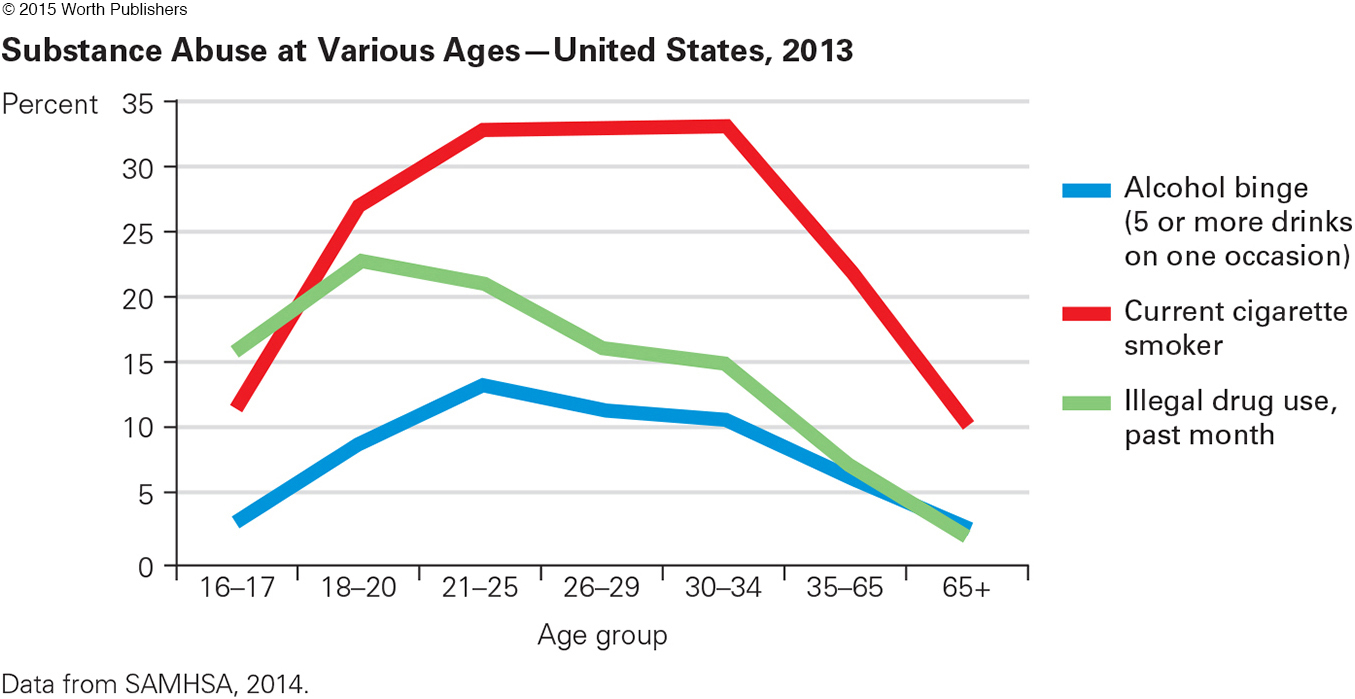

Illegal drug use peaks at about age 20 and declines sharply with age (see Figure 11.2). Addiction to legal drugs (no arrest imminent) may continue in adulthood, but after age 25, most who drink and smoke to excess want to quit.

Quitting an addictive drug is difficult at any age, but as the years go on, adults no longer enjoy the taste, the thrill, or the sensation as they once did. They use drugs to relieve anxiety, or out of habit, not primarily for pleasure. For that reason, abstinence becomes more common, a source of pride not embarrassment, after emerging adulthood (Heyman, 2013).

Drug abuse is more frequent among college students than among emerging adults who are not in college, partly because groups of emerging adults urge each other on. For instance, some hazing rituals for college fraternities involve excessive consumption of alcohol. Such forced drinking is a symptom of a general problem: One study found that 25 percent of young college men consumed 10 or more drinks in a row at least once in the previous two weeks (Johnston et al., 2009).

In the United States, the problem is not confined to men. A nationwide study found that 24 percent of women aged 18–

THINK CRITICALLY: Why are wealthier emerging adults more likely to drink too much alcohol than their less wealthy contemporaries?

Many colleges try to reduce alcohol consumption and enforce age restrictions—

Video: College Binge Drinking shows college students engaging in (and rationalizing) this risky behavior.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 11.2

1. Why is maximum physical strength usually attained in emerging adulthood?

Every human body system is at optimal physical functioning during emerging adulthood. Many serious diseases have not yet developed, and some childhood ailments are outgrown. Physiologically, the early 20s are considered the prime of life.

Question 11.3

2. What has changed, and what has not changed, in the past decades regarding sexual and reproductive development?

Whereas in previous generations, when couples married around age 20 and had their first child within a few years of marriage, they are now more likely to wait to get married. This is in part due to modern contraception, which has enabled sex without marriage.

Question 11.4

3. Why are STIs more common today than they were 50 years ago?

There is a consequence of sexual freedom: the rise of STIs. The single best way to prevent STIs is lifelong monogamy, but most emerging adults practice serial monogamy, beginning a new relationship soon after one ends. At times a new sexual liaison overlaps an existing one, and sometimes a steady relationship is interspersed with a fling with someone else.

Question 11.5

4. What are the social benefits of risk taking?

Many occupations are filled with risk takers—

Question 11.6

5. Why are some sports more attractive to emerging adults than to other adults?

Emerging adults may take part in risky sports such as motocross or snowboarding because they seek an adrenaline rush. The desire to experience a thrill may also overwhelm their ability to evaluate the potential risks associated with the activity, making emerging adults less concerned with the possibility of injury or death.

Question 11.7

6. Why are serious accidents more common in emerging adulthood than later?

Many emerging adults bravely, or foolishly, risk their lives. The reasons for such risk-

Question 11.8

7. Why are college students more likely to abuse drugs than those who are not in college?

Drug abuse—