Cognitive Development

Piaget changed our understanding of cognitive development by recognizing that maturation does not simply add knowledge; it allows a leap forward at each stage, first from sensorimotor to preoperational because of language (symbolic thought), and then with more advanced logical operations, from preoperational to concrete to formal (analytic).

Many cognitive psychologists find that post-

Postformal Thought and Brain Development

postformal thought

A proposed adult stage of cognitive development. Postformal is more practical, flexible, and dialectical (i.e., more capable of combining contradictory elements into a comprehensive whole) than earlier cognition.

Some developmentalists propose a fifth stage, called postformal thought, a “type of logical, adaptive problem–

As you remember from Chapter 9, adolescents use two modes of thought (dual processing) but have difficulty combining them. They use formal analysis to learn science, distill principles, develop arguments, and resolve the world’s problems. Alternatively, they think spontaneously and emotionally about personal issues, such as what to wear, whom to befriend, whether to skip class. For personal issues, they prefer quick actions and reactions, only later realizing the consequences.

Postformal thinkers are less impulsive and reactive. They take a more flexible and comprehensive approach, with forethought, noting difficulties and anticipating problems, instead of denying, avoiding, or procrastinating. As a result, postformal thinking is more practical, creative, and imaginative than thinking in previous cognitive stages (Wu & Chiou, 2008). It is particularly useful in human relationships (Sinnott, 2014).

As you have read, some, but certainly not all, developmentalists dispute Piaget’s stage theory of childhood cognition. The ranks of dissenters swell regarding this fifth stage. As two scholars writing about emerging adulthood ask, “Who needs stages anyway?” (Hendry & Kloep, 2011).

Piaget himself never used the term postformal. If the definition of cognitive stage is to attain a new set of intellectual abilities (such as the symbolic use of language that distinguishes sensorimotor from preoperational thought), then adulthood has no stages.

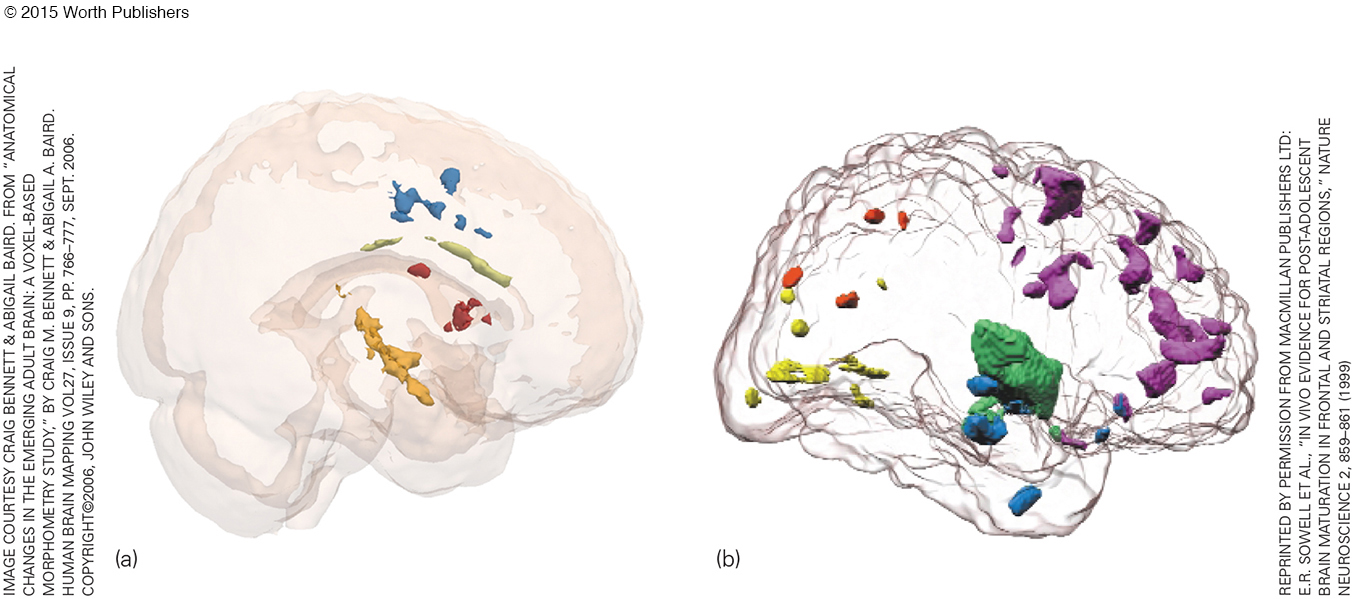

However, the prefrontal cortex is not fully mature until the early 20s, and new dendrites connect throughout life. As more is understood about brain development after adolescence, it seems likely that thinking changes as the brain matures. Of course, maturation never works alone. Several studies find that adult cognition benefits from the varied experiences of the social world beyond home and neighborhood that typically occur during emerging adulthood (Sinnott, 2014).

Piaget may have envisioned a fifth stage, according to one scholar:

we hypothesize that there exists, after the formal thinking stage, a fifth stage of post-

[Lemieux, 2012, p. 404]

Try Video Activity: Brain Development: Emerging Adulthood for a quick look at the changes that occur in a person’s brain between ages 18 and 25.

COUNTERING STEREOTYPES Cognitive flexibility, particularly the ability to change childhood assumptions, helps counter stereotypes. Young adults show many signs of such flexibility. The very fact that emerging adults did marry later than previous generations shows that, couple by couple, thinking is not determined by childhood culture or by traditional norms. Early experiences are influential, but postformal thinkers are not stuck by them.

Research on racial prejudice is another example. Many people are less prejudiced than their parents. This is a cohort change. However, emerging adults may overestimate the change. Tests often reveal implicit discrimination. Thus, many adults have both unconscious prejudice and rational tolerance—

The wider the gap between explicit and implicit, the stronger the stereotypes (Shoda et al., 2014). Ideally, postformal reasoning allows rational thinking to overcome emotional reactions, with responses dependent on reality, not stereotypes (Sinnott, 2014). A characteristic of adult thinking may be the flexibility that allows recognition and reconciliation of contradictions, thus reducing prejudice.

stereotype threat

The thought that one’s appearance or behavior might confirm another person’s oversimplified, prejudiced attitudes, a thought that causes anxiety even when the stereotype is not held by other people.

Unfortunately, many young people do not recognize their own stereotypes, even when false beliefs harm them. One of the most pernicious results is stereotype threat, arising in people who worry that other people might judge them as stupid, lazy, oversexed, or worse because of their ethnicity, sex, age, or appearance.

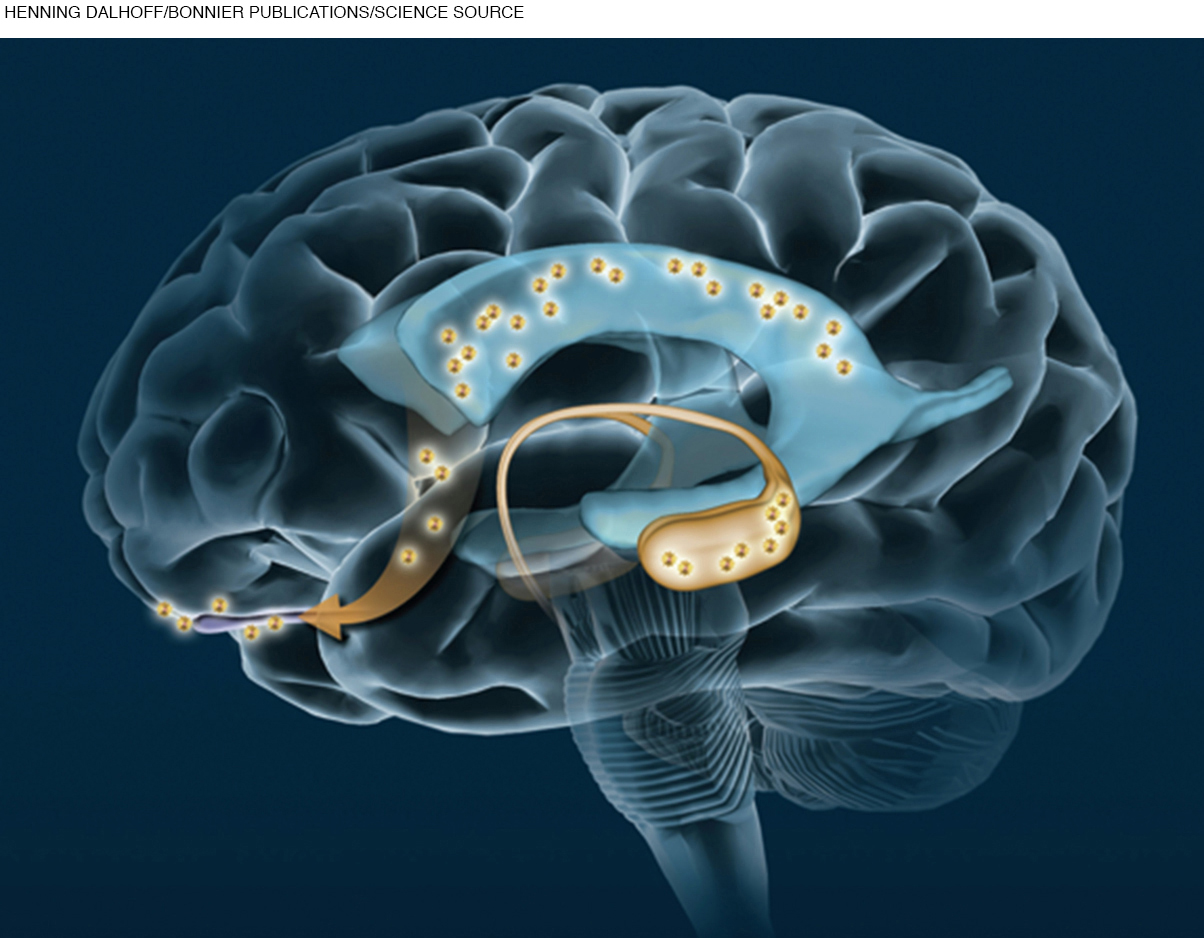

The idea is that people have a stereotype that other people have a stereotype. Then the possibility of being stereotyped arouses emotions and hijacks memory, disrupting cognition (Schmader, 2010). That is stereotype threat, as further explained below.

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Stereotype Threat

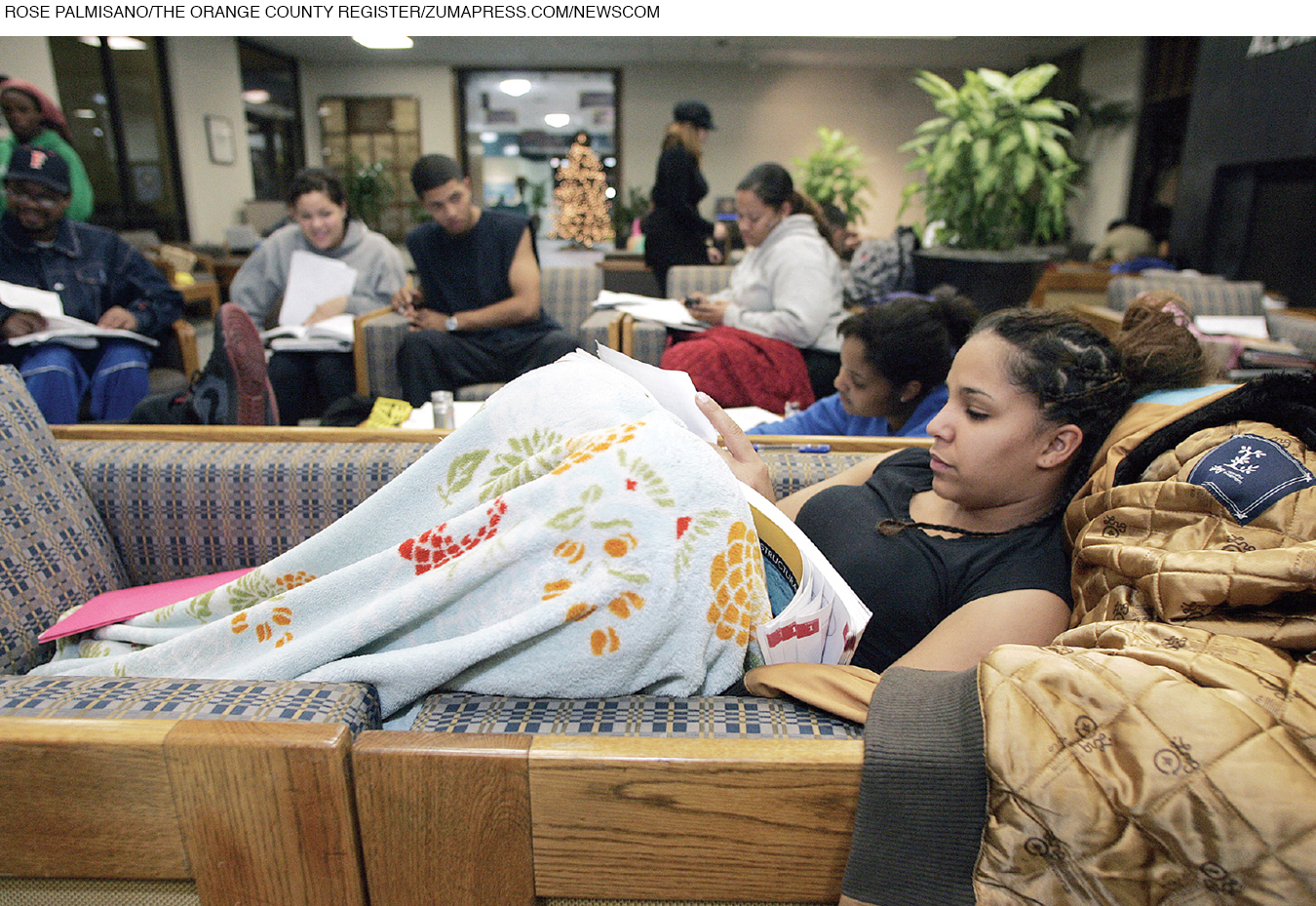

One statistic has troubled social scientists for decades: African American men have lower grades in high school and earn only half as many college degrees as African American women (Chronicle of Higher Education, 2014). This cannot be genetic, since the women have the same genes (except one chromosome) as the men.

Most scientists have blamed the historical context as well as current discrimination, which falls particularly hard on men. Even today, African American women have an easier time finding employment, and the unarmed African Americans who are killed are almost always men (recent examples that became nationally known: Martin, Brown, Garner, Gray, Scott).

Another hypothesis focuses on parenting. According to one study, African American mothers in particular grant far more autonomy to their teenage boys and have higher and stricter standards of achievement for their teenage girls (Varner & Mandara, 2014). These researchers suggest that if sons and daughters were treated equally, most gender differences in achievement would disappear.

One African American scholar, Claude Steele, thought of a third possibility, that the problem originated in the mind, not in the family or society. He labeled it stereotype threat, a “threat in the air,” not in reality (Steele, 1997). The mere possibility of being negatively stereotyped may disrupt cognition and emotional regulation.

Steele suspected that African American males who know the stereotype that they are poor scholars will become anxious in educational settings. Their anxiety may increase stress hormones that reduce their ability to respond to intellectual challenges.

Then, if they score low, they protect their pride by denigrating academics. They come to believe that school doesn’t matter, that people who are “book smart” are not “street smart.” That belief leads them to disengage from high school and college, which results in lower achievement. The greater the threat, the worse they do (Taylor & Walton, 2011).

Stereotype threat is more than a hypothesis. Hundreds of studies show that anxiety reduces achievement. The threat of a stereotype causes women to underperform in math, older people to be forgetful, bilingual students to stumble with English, and every member of a stigmatized minority in every nation to handicap themselves because of what they imagine others might think (Inzlicht & Schmader, 2012).

Not only academic performance but also athletic prowess and health habits may be impaired if stereotype threat makes people anxious (Aronson et al., 2013). Every sphere of life may be affected. One recent example is that blind people are underemployed if stereotype threat makes them hesitate to learn new skills (Silverman & Cohen, 2014).

The worst part of stereotype threat is that it is self-

The harm from anxiety is familiar to those who study sports psychology. When star athletes unexpectedly under perform (called “choking”), stereotype threat arising from past team losses may be the cause (Jordet et al., 2012). Many female players imagine they are not expected to play as well as men (e.g., someone told them “you throw like a girl”), and that itself impairs performance (Hively & El-

The next step for many developmentalists is figuring out how stereotype threat can be eliminated, or at least reduced (Inzlicht & Schmader 2012; Sherman et al., 2013; Dennehy et al., 2014). Reminding people of their own potential, and the need to pursue their goals, is one step. The questions for each of us are, what imagined criticisms from other people impair our own achievement, and how do we overcome that?

The Effects of College

A major reason why emerging adulthood has become a new period of development, when people postpone the usual markers of adult life (marriage, a steady job), is that many older adolescents seek further education instead of taking on adult responsibilities.

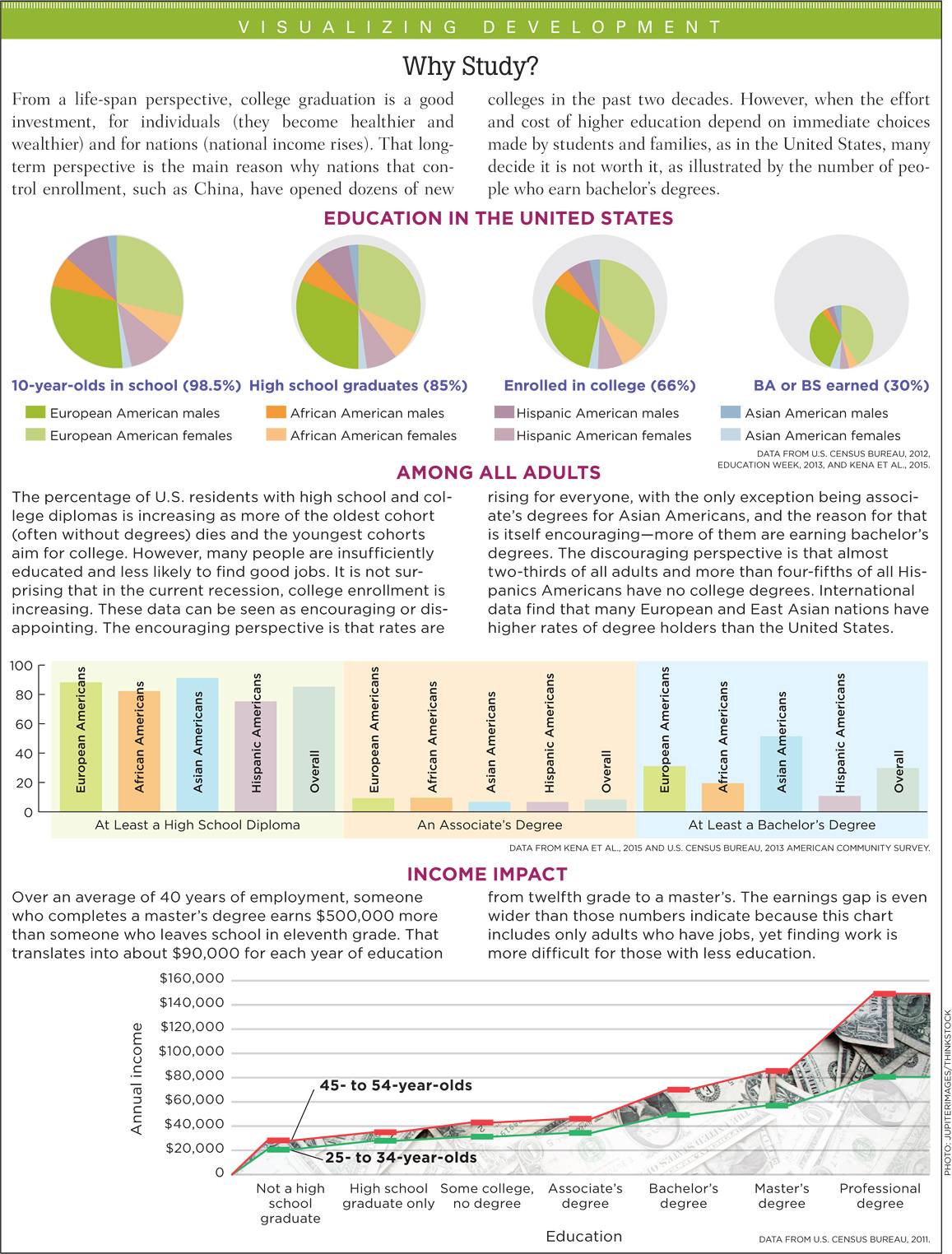

MASSIFICATION There is no dispute that tertiary education improves health and wealth. The data on virtually every physical condition, and every indicator of material success, show that college graduates are ahead of high school graduates, who themselves are ahead of those without a high school diploma. This is apparent even when the comparisons are between students of equal ability: It’s the education, not just the potential, that makes a difference.

Because of that, every nation has increased the number of college students. This is a phenomenon called massification, based on the idea that college could benefit almost everyone (the masses) (Altbach et al., 2010).

The United States was the first major nation to endorse massification, with state-

Recently, however, other nations have increased public funding for college while the United States has decreased it. As a result, eleven other nations have a higher proportion of 25-

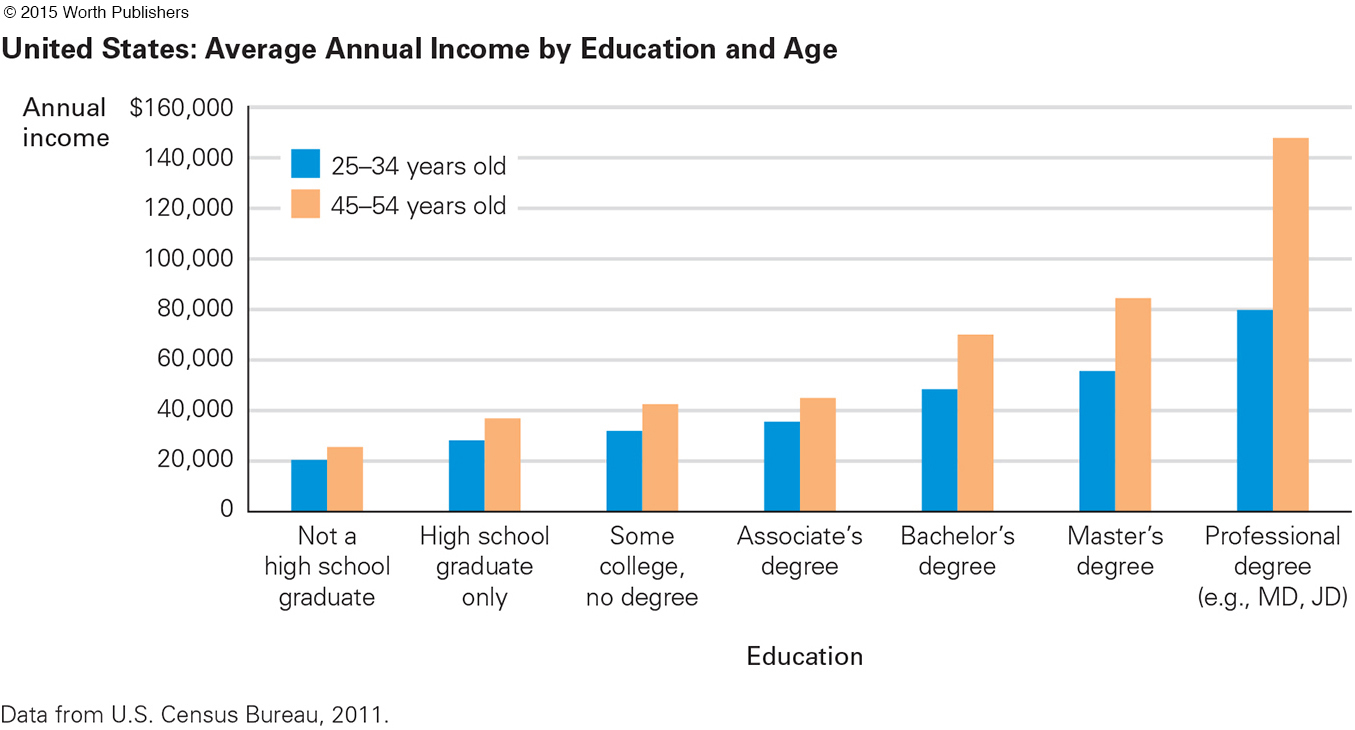

U.S. Census data and surveys of individuals find that college education pays off for individuals as well as for societies more than it did 30 years ago. The average college man earns an additional $17,558 per year compared to a high school graduate. Women also benefit, but not as much, earning $10,393 more per year (Autor, 2014). That higher salary is averaged over the years of employment: Most new graduates do not see such a large wage difference; but in a decade or two, the differences are dramatic.

The reasons for the gender gap are many. Some observers blame culture, some blame employers, and others blame the women themselves, who are less likely to demand more pay. Even among contemporary emerging adults, women seem to undervalue their worth (stereotype threat again). This was one conclusion of a series of experiments with college students in which women were more likely to attribute success of a team project to a male partner than to themselves (Haynes & Heilman, 2013).

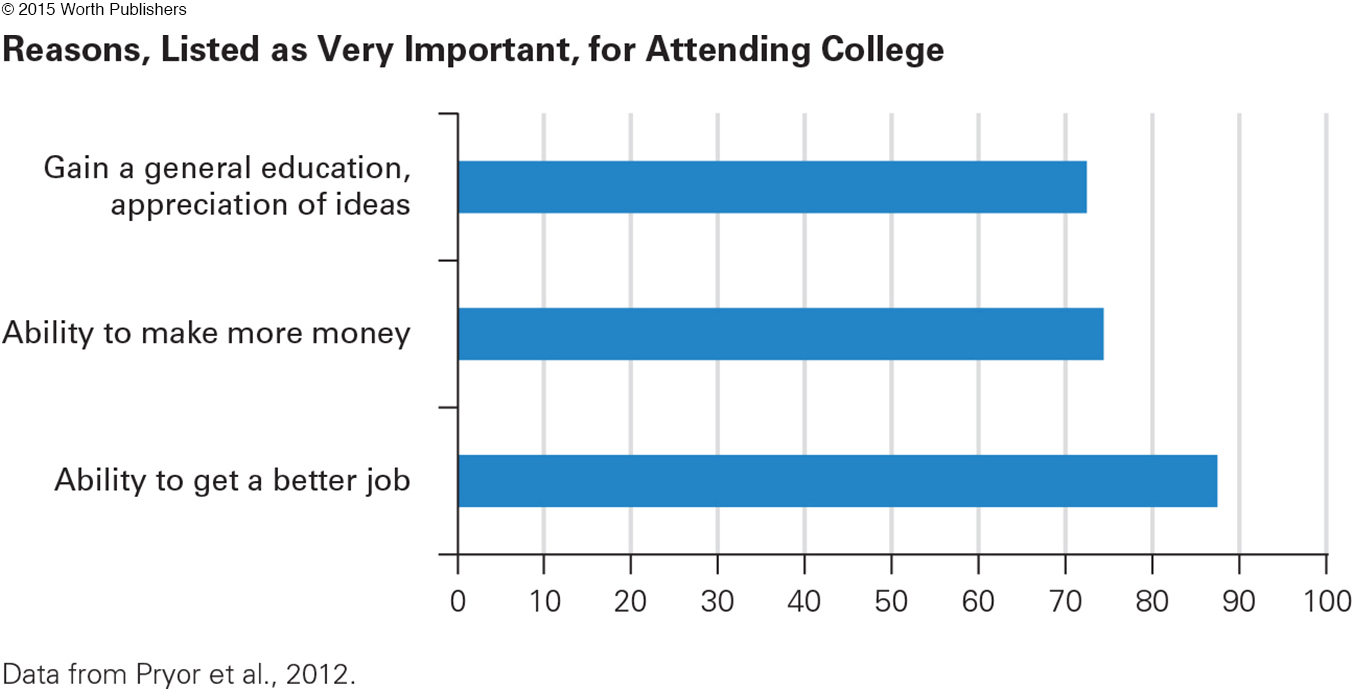

DEBTS AND DROPOUTS The typical American with a master’s degree earns twice as much as the typical one with only a high school diploma (Doubleday, 2013) (see Figure 11.3), but most U.S. adults believe that college is too expensive. According to a survey, 94 percent of parents expect their children to go to college, but 75 percent of the public (parents or not) believe that college costs are beyond what most parents can afford (Pew Research Center, May 17, 2012).

The longitudinal data make it clear that a college degree is worth the expense and that investing in college education returns the initial expense more than five times. That means if a student spends a nickel now, they get a quarter back in a few years, or if a degree costs $200,000, over a lifetime the return is a million dollars.

However, there is a major problem with that calculation. Although most freshmen expect to graduate, many of them leave college before graduating. Some income benefits come from simply attending college, but most result from earning a degree. Yet the costs come from enrolling, not from graduating, so the benefits may be far less than the million dollars mentioned in the previous paragraph.

Statistics on college graduation are discouraging. Even six years after entering a college designed to award a bachelor’s degree after four years of study, less than half the students graduate. Data from 2013 find that only 34 percent of the students at private, for-

Ironically, schools with the lowest graduation rates are the most popular: 2,352,054 students attend for-

The sad truth is that many freshmen will be disappointed: Almost all (88 percent) expect to earn a degree in four years, and many (76 percent) expect a master’s or professional degree after completing their bachelor’s (Chronicle of Higher Education, 2014). Rates of completed advanced degrees are also discouraging.

One effort to improve graduation rates is to make college loans easier to obtain so that fewer students leave because they cannot afford college or because their paid job interferes with study time. However, for some emerging adults, paying back loans is a major burden, especially because interest on those loans is high. Many analysts question the impact of such loans, which may burden students, taxpayers, and society without increasing graduation rates or employment prospects (Best & Best, 2014; Webber, 2015).

Nonetheless, every study over the past several decades reaches the same conclusion: When 18-

The financial benefits of college seem particularly strong for ethnic minorities and low-

COLLEGE AND COGNITION For developmentalists interested in cognition, the crucial question about college education is not about wealth, health, rates, expense, or even graduation. Instead, developmentalists wonder whether college advances critical thinking and postformal thought. The answer seems to be yes, but some studies dispute that.

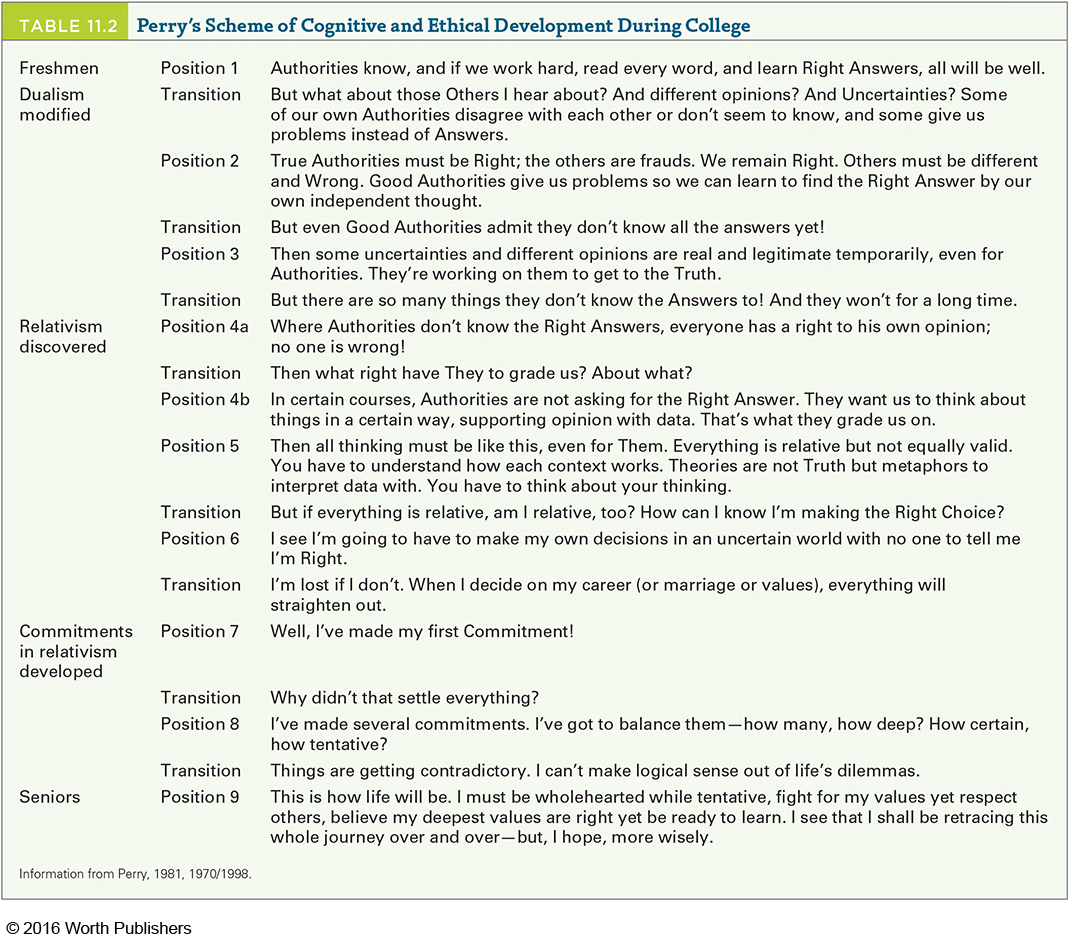

Let us begin with the classic work of William Perry (1981, 1970/1998). After repeatedly questioning students at Harvard, Perry described students’ thinking through nine levels of complexity over the four years that led to a bachelor’s degree (see Table 11.2).

Perry found that freshmen arrived thinking in a simplistic dualism. Most tended to think in absolutes, believing that things were either right or wrong. Answers to questions were yes or no, the future led to success or failure, and the job of the professor (Authorities) was to distinguish between the two and then tell the students.

By the end of college, Perry’s subjects believed strongly in relativism, recognizing that many perspectives might be valid and that almost nothing was totally right or wrong. But they were able to overcome that discouraging idea: They had become critical thinkers, realizing that they needed to move forward in their lives by adopting one point of view, yet expecting to change their thinking if new challenges and experiences produced greater insight.

Perry found that the college experience itself caused this progression: Peers, professors, books, and class discussion all stimulated new questions and thoughts. Other research confirmed Perry’s conclusions. In general, the more years of higher education a person had, the deeper and more postformal that person’s reasoning became (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991).

CURRENT CONTEXTS But wait. You probably noticed that Perry’s study was first published decades ago. Hundreds of other studies in the twentieth century also found that college deepens cognition. Since you know that cohort and culture are influential, you are right to wonder whether those conclusions still hold in the twenty-

Many recent books criticize college education on exactly those grounds. Notably, a twenty-

The reasons were many. Compared to decades ago, students study less, professors expect less, and students avoid classes that require reading at least 40 pages a week or writing 20 pages a semester. Administrators and faculty still hope for intellectual growth, but rigorous classes are canceled, not required, or taken by only a few.

A follow-

Other observers blame the exosystem for forcing colleges to follow a corporate model with students as customers who need to be satisfied rather than youth who need to be challenged (Deresiewicz, 2014). Customers, apparently, demand dormitories and sports facilities that are costly, and students take out loans to pay for them. The fact that the United States has slipped in massification is not surprising, given the political, economic, and cultural contexts of contemporary college.

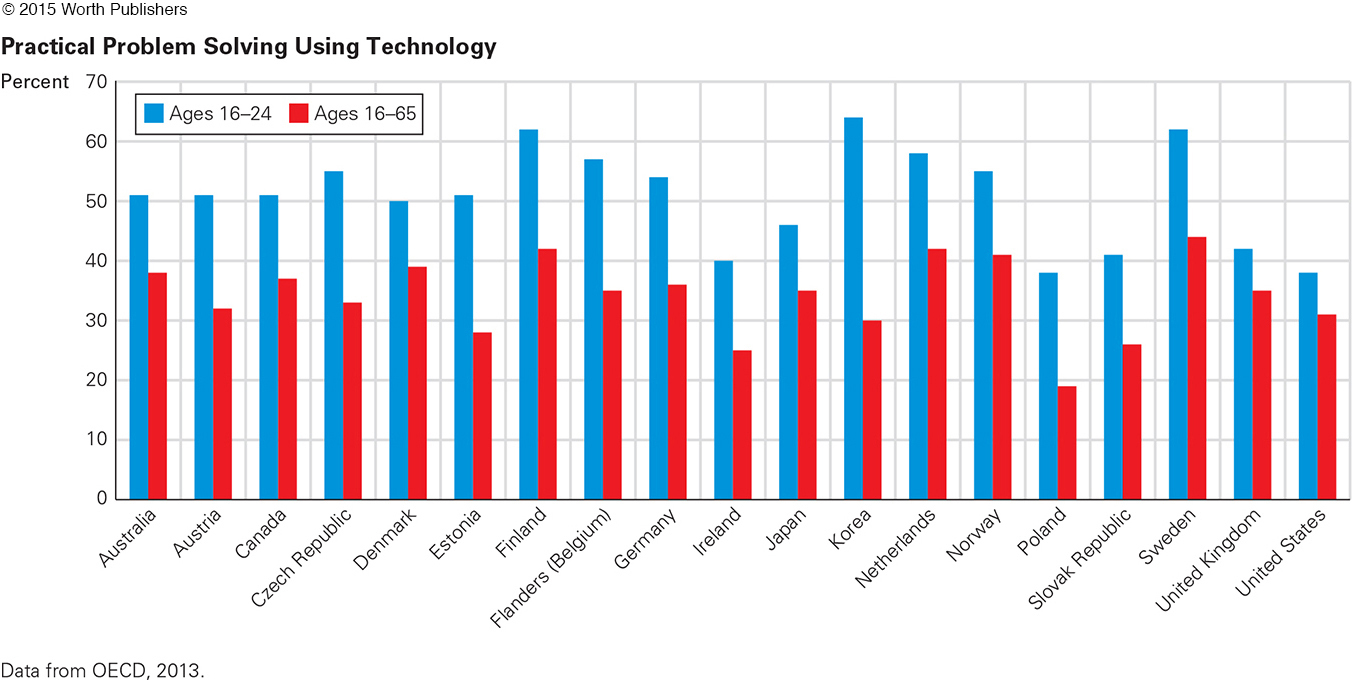

A related development is that U.S. young adults are less proficient in various skills, including reading comprehension, problem solving, and especially math, according to international tests (see Figure 11.4). A report highlighting those results is particularly critical of the disparity in education between the rich and the poor, stating “to put it bluntly, we no longer share the growth and prosperity of the nation the way we did in the decades between 1940 and 1980” (Goodman et al., 2015, p. 2).

Two new pedagogical techniques may foster greater learning, or may be evidence of the decline of standards. One is called the flipped class, in which students are required to watch videos of a lecture on their computers or other devices before class. They then use class time for discussion, with the professor prodding and encouraging but not lecturing.

massive open online courses (MOOCs)

College courses that are offered solely online. Typically, thousands of students enroll.

The other technique is classes that are totally online, including massive open online courses (MOOCs). A student can enroll in such a class and do all the work off campus. Among the advantages of MOOCs is that students can be anywhere.

Question 11.9

OBSERVATION QUIZ

In what nation do emerging adults excel the most compared to older adults, and in what nation is the contrast smallest?

Most—

For example, MOOCs have enrolled students who are: in rural areas far from college; unable to leave home because they have young children or mobility problems; serving in the armed forces far from college; living in countries with few rigorous or specialized classes. The first MOOC offered by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard enrolled 155,000 students from 194 nations, including 13,044 from India (Breslow et al., 2013).

Only 4 percent of the students in that first MOOC completed the course. Completion rates have risen in later courses, but almost always the dropout rate is over 80 percent. Researchers agree that “learning is not a spectator sport,” that active engagement, not merely clicking on a screen, is needed for education. Although MOOCs are attractive for many reasons, colleges are wary of “knee-

The crucial variable may be the students. MOOCs are most successful if students are highly motivated, adept at computer use, and have the needed prerequisites (Reich, 2015). That first MIT course had many enrollees who did not have the necessary math skills (Breslow et al., 2013).

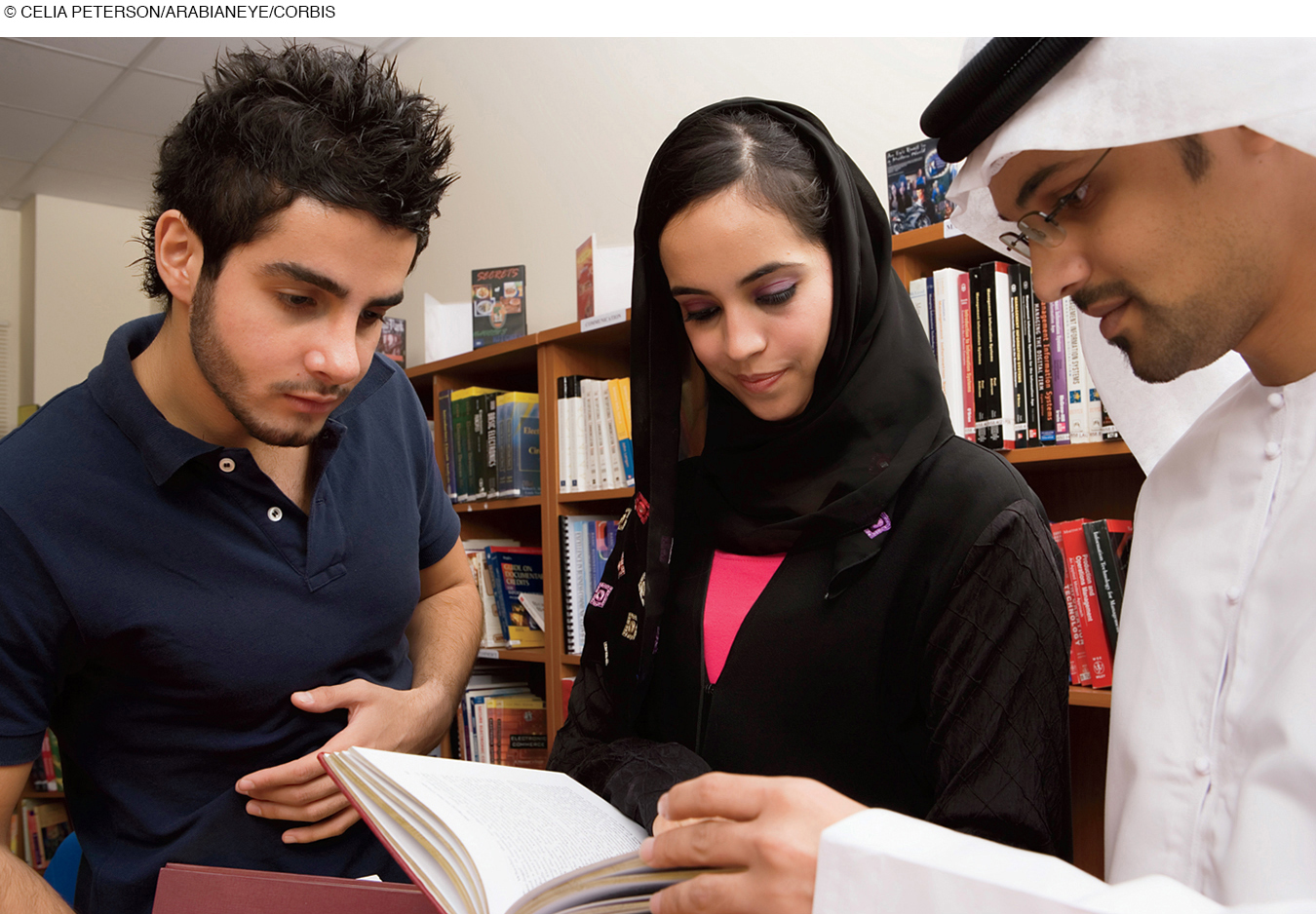

Students learn best in MOOCs if they have another classmate, or an expert, as a personal guide. This is true for all kinds of college learning: Face-

MOTIVATION TO ATTEND COLLEGE Motivation is crucial for every intellectual accomplishment. An underlying problem in the controversy about college education is that people disagree about its purpose, and thus, students who are motivated to accomplish one thing clash with professors who are motivated to teach something else. Parents and governments who subsidize college may have a third goal in mind.

Video: The Effects of Mentoring on Intellectual Development: The University-

Developmentalists, most professors, and many college graduates believe that the main purpose of higher education is “personal and intellectual growth,” which means that professors should focus on fostering critical thinking and analysis. However, adults who have never attended college believe that “acquiring specific skills and knowledge” is more important. For them, success is a high-

In the Arum and Roksa report (2011), students majoring in business and other career fields were less likely to gain in critical thinking compared to those in the liberal arts (courses that demand more reading and writing). These researchers suggest that colleges, professors, and students themselves who seek easier, more popular courses are short-

However, many students attend college primarily for career reasons (see Figure 11.5). They want jobs with good pay; they select majors and institutions accordingly, not for intellectual challenge and advanced communication skills. Business has become a popular major. Professors are critical when college success is measured via the future salaries of graduates, but that metric may be what the public expects. Cohorts clash.

In 1955, most U.S. colleges were four-

No nation has reached consensus on the purpose of college. For example in China, where the number of college students now exceeds the U.S. number (but remember that the Chinese population is much larger), the central government has fostered thousands of new institutions of higher learning. The main reason is to provide more skilled workers for economic advancement, not to deepen intellectual understanding and critical thinking. However, even in that centralized government, disagreement about the goals and practices of college is evident (Ross & Wang, 2013).

For example, in 2009, a new Chinese university (called South University of Science and Technology of China, or SUSTC) was founded to encourage analysis and critical thinking. SUSTC does not require prospective students to take the national college entry exam (Gao Kao); instead, “creativity and passion for learning” are the admission criteria (Stone, 2011, p. 161).

THINK CRITICALLY: What is the purpose of college education?

It is not clear whether SUSTC is successful, again because people disagree about how to measure success. The Chinese government praises SUSTC’s accomplishments but has not replicated it (Shenzhen Daily, 2014).

The Effects of Diversity

One development of the twenty-

DIVERSITY IN COLLEGE The most obvious diversity in colleges worldwide is gender: In 1970, at least two-

A historic example is Virginia Military Institute (VMI), a state-

In addition to gender diversity, students’ ethnic, economic, religious, and cultural backgrounds are more varied. Compared to 1970, more students are parents, are older than age 24, are of non-

In the United States, when undergraduate and graduate students are tallied by ethnicity, 35 percent are “minorities” of some kind (Black, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander, two or more races). Faculty members are also more diverse; 19 percent are non-

These numbers overstate diversity: It is not true that most colleges are a third minority. Instead, some colleges are almost exclusively minority (usually only one minority, as with historically African American or Native American colleges). Many other colleges are almost entirely European American, as are most tenured professors. Further, the typical college student is still 18 to 22 years old and attends college full-

DIVERSITY AS THOUGHT-

Colleges that make use of their diversity—

Such advances are not guaranteed. Emerging adults, like people of every age, tend to feel most comfortable with people who agree with them. Critical thinking develops outside the personal comfort zone, when cognitive dissonance requires deeper thought.

Regarding colleges, some people hypothesize that critical thinking is less likely to develop when students enroll in colleges near home or when they join fraternities or sororities. However, that hypothesis does not seem valid (Martin et al., 2015).

The crucial factor seems to be honest talk with a peer who differs in background and values, and that can happen in many places—

Again, meeting people who are from various backgrounds is a first step. For cognitive development to occur, the willingness to listen to someone with opinions unlike one’s own, and to modify one’s own thinking accordingly, is crucial. That openness, and flexibility, is characteristic of postformal thought.

The validity of this conclusion is illustrated by the remarkable acceptance of homosexuality over the past 50 years, not only in recognition of marriage but in everything from bullying in middle school to adoption of children by gay and lesbian parents. Fourteen percent of Americans—

The main reason that individuals became more accepting of homosexuality is that people realized that they knew LGBT people personally (Pew Research Center, March 20, 2013). That occurred not only because people were more open about their sexual orientation but also because young adults in particular spoke with their LGBT peers. The research finds that those in the vanguard of this social revolution were emerging adults, for all the reasons just described about cognitive development.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 11.10

1. Why did scholars choose the term postformal to describe the fifth stage of cognition?

The term postformal thought originated because several developmentalists agreed that Piaget’s fourth stage, formal operational thought, was inadequate to describe adult thinking.

Question 11.11

2. How does postformal thinking differ from typical adolescent thought?

In contrast to typical adolescent thought, postformal thought is more practical, more flexible, and is dialectical. It engages in problem finding in addition to the problem solving of adolescent thought, and has the ability to combine emotion and logic. Emerging adults tend to be more practical, creative, and innovative in thinking than adolescents. Emerging adults, in contrast to adolescents, combine both emotions and logic in thought.

Question 11.12

3. Why might the threat of a stereotype affect cognition?

The mere possibility of being negatively stereotyped arouses emotions that can disrupt cognition as well as emotional regulation. The worst part of stereotype threat is that it is self-

Question 11.13

4. Who is vulnerable to stereotype threat and why?

Stereotype threat has been shown with hundreds of studies on dozens of stereotyped groups, of every ethnicity, sex, sexual orientation, and age.

Question 11.14

5. How do current college enrollment patterns differ from those of 50 years ago?

College is no longer for the elite few. There is more gender, ethnic, economic, religious, and cultural diversity in the student body. Courses of study—

Question 11.15

6. How has college attendance changed internationally in recent decades?

College attendance has increased dramatically in other nations, as a result of increased public funding for college. This is in contrast to the United States, which has steadily decreased its public funding for college in recent years.

Question 11.16

7. Why do people disagree about the goals of a college education?

Developmentalists, academics, and many college graduates may believe that the main purpose of a college education is to gain critical thinking and analytic skills, but adults who have never attended college believe that learning the skills needed to attain a high-

Question 11.17

8. In what way does exposure to diversity affect college students’ learning?

Exposure to diversity advances cognition, in that honest conversations among people of different backgrounds and varied perspectives lead to intellectual challenge and deeper thought.