Personality Development in Adulthood

Remember from Chapter 4 that every infant is born with a unique temperament and from Chapter 6 that parents have diverse parenting styles. That is part of what makes up adult personality, but there is much more. Like a tree adding another ring of growth each year, an ongoing mixture of genes, experiences, and cultures results in each person’s unique actions, emotions, and attitudes, a combination called personality.

Continuity is evident: Few adults develop characteristics that are the reverse of their childhood temperament. But one noteworthy finding about adulthood is that people can change, not only in actions but also in personality, usually for the better.

Theories of Adult Personality

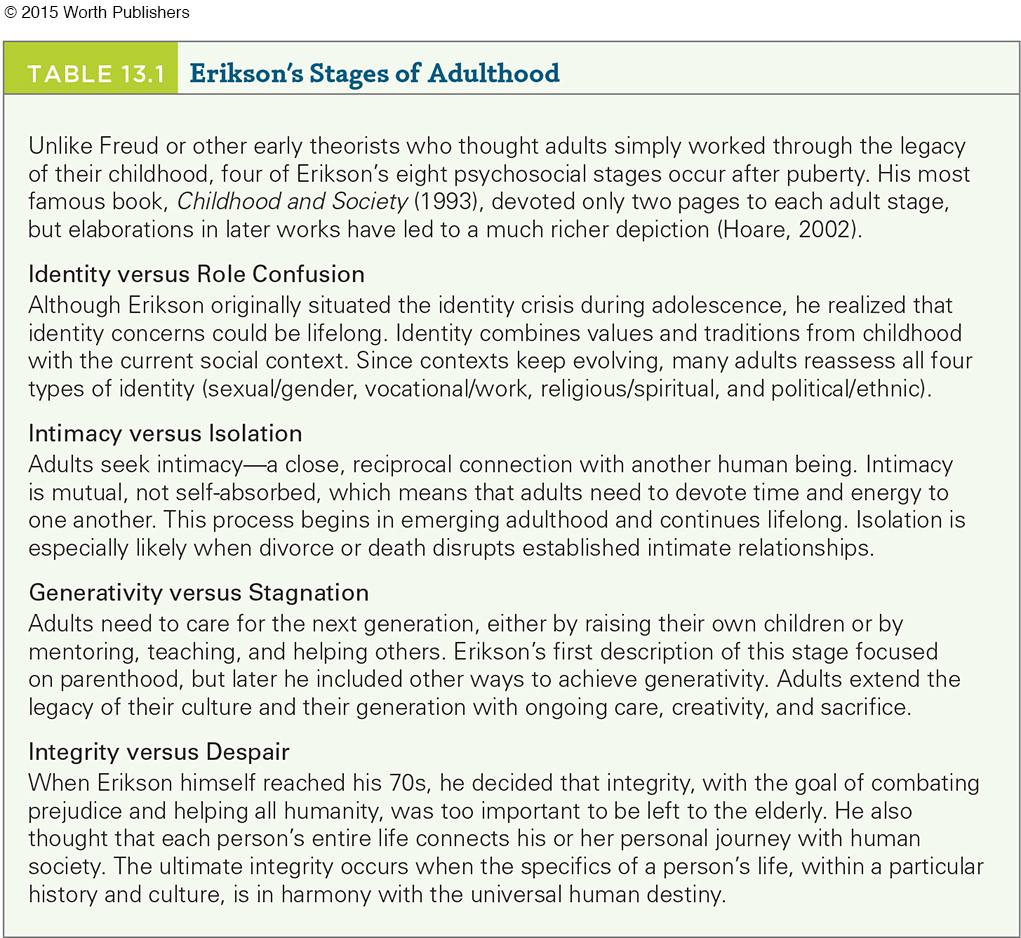

Erikson originally described eight stages of development. His first five stages (already explained) each begin in a particular chronological period. But adult stages are less age-

Chronological age is an imperfect marker in adulthood. The three adult stages—

Further, adult stages disappear and reappear. For example, intimacy needs may seem satisfied in early adulthood with a good marriage, but then they may reappear decades later after an unanticipated divorce.

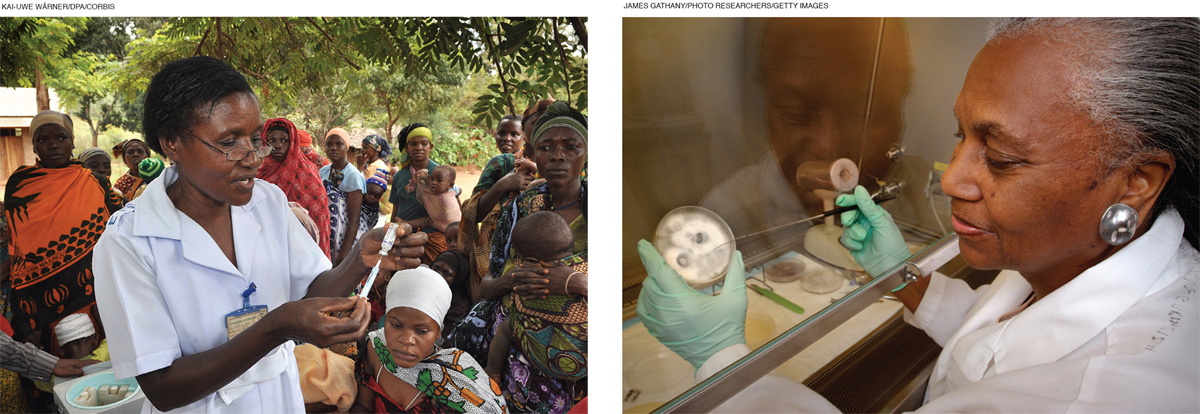

Maslow’s hierarchy of five needs (explained in Chapter 1) is thought to characterize everyone. Unless mired in poverty or war, or suffering from severe early trauma, adults have moved past the two lower stages (safety and basic needs) and seek love and then respect (levels three and four). Only a few reach self-

Not only Maslow and Erikson, but also every well-

Personality Traits

Some babies are shy, others outgoing; some are frightened, others fearless. Such traits begin with genes, but they are affected by experiences.

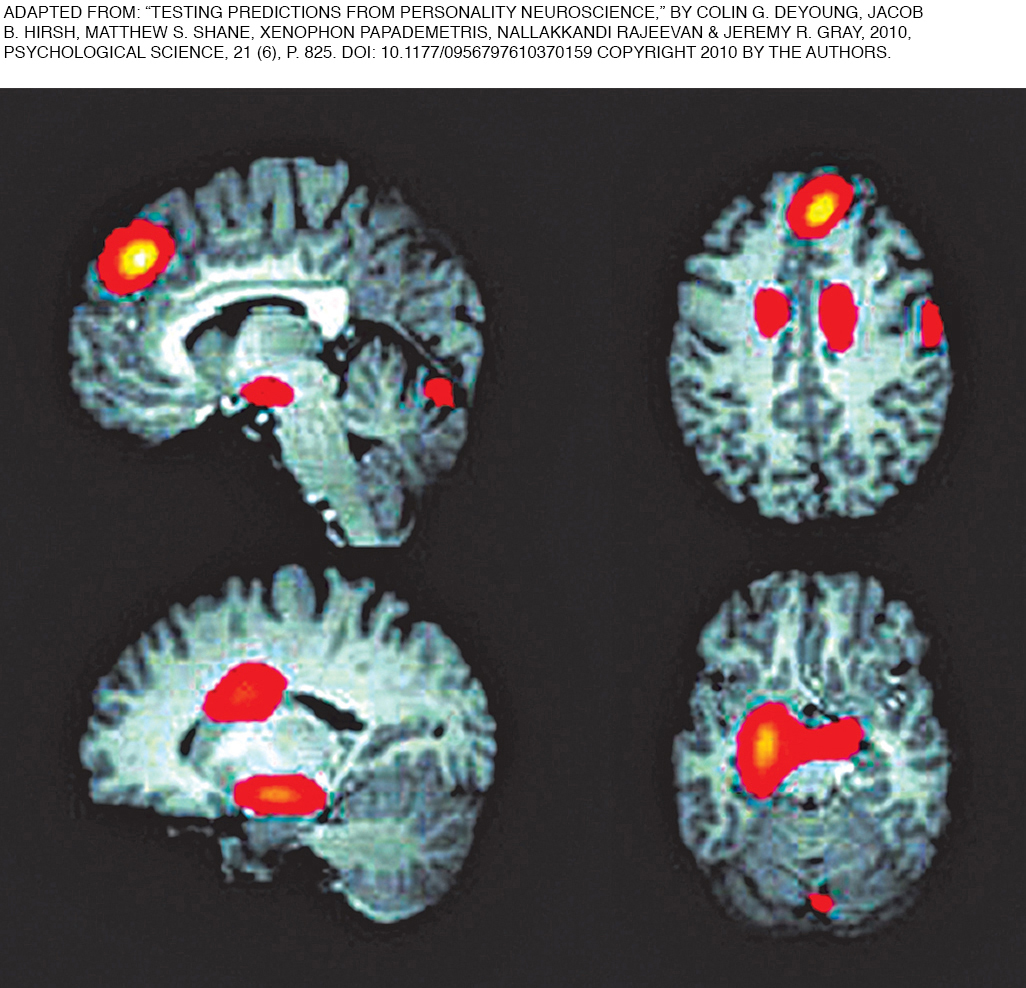

THE BIG FIVE Temperament is partly genetic; genes are lifelong. There are hundreds of examples, some that are surprising. One study found, for instance, that temperament at age 3 predicted gambling addiction at age 32 (Slutske et al., 2012).

Big Five

The five basic clusters of personality traits that remain quite stable throughout adulthood: openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

Longitudinal, cross-

Openness: imaginative, curious, artistic, creative, open to new experiences

Conscientiousness: organized, deliberate, conforming, self-

disciplined Extroversion: outgoing, assertive, active

Agreeableness: kind, helpful, easygoing, generous

Neuroticism: anxious, moody, self-

punishing, critical

Each person’s personality is somewhere between extremely high and extremely low on each of these five. The low end might be described, in the same order as above, with these five adjectives: closed, careless, introverted, hard to please, and placid.

Adults choose their contexts, selecting vocations, hobbies, health habits, mates, and neighborhoods in part because of their own traits. Personality affects almost everything, including whether an emerging adult develops an eating disorder, an adult becomes an impulsive shopper, or an older adult retires (Sansone & Sansone, 2013; Thompson & Prendergast, 2015; Robinson et al., 2010).

Among the actions and attitudes linked to the Big Five are education (conscientious people are more likely to complete college), cheating on exams (low on agreeableness), marriage (extroverts more often marry), divorce (more likely for neurotics), IQ (higher in openness), verbal fluency (again, openness and extroversion), and even political views (conservatives less open) (Duckworth et al., 2007; Gerber et al., 2011; Silvia & Sanders, 2010; Giluk & Postlethwaite, 2015).

International research confirms that human personality traits (there are hundreds of them) can be grouped in the Big Five (Carlo et al., 2014), although some scholars believe another list of five or six might be better. Everyone agrees that personality is influenced by many factors beyond temperament. The paragraph above notes tendencies, not always realities. People try to shape their personality to the norms of their culture. As one team wrote, “personality may acculturate” (Güngör et al., 2013, p. 713).

THINK CRITICALLY: Would your personality fit better in another culture?

Generally, a study of well-

AGE AND COHORT Many researchers find that personality shifts slightly with age, but the rank order of various traits stays the same. Thus, 20-

The general age trend is positive. People are more likely to grow closer to their cultural norms, as well as to become more stable in their traits. Personality change, if it ever is to occur, is more likely early or late in life, not in the middle (Specht et al., 2011).

Traits that are considered pathological (such as neuroticism) tend to be modified as people mature. By contrast, traits that are valued (such as conscientiousness) increase slightly (L. Clark, 2009; Lehman et al., 2013). Not surprisingly, then, self-

Both nature and nurture are always relevant, but the power of each may be affected by a person’s age. People under the age of 30 “actively try to change their environment,” moving away from home and finding new friends, changing their nurture. Later in life, context shapes traits, because once adults have chosen their vocation, family, and neighborhoods, they “change the self to fit the environment” (Kandler, 2012, p. 294).

Cohort is important too, affecting the interaction of personality and behavior. This is evident in one of the most important decisions an adult must make—

For both men and women born in 1920, those high in openness had about the same number of children as those low in that trait because the entire culture valued fertility. Consequently, no matter what an individual’s personality, everyone hoped to marry and have several children unless biology made that impossible.

For those born in 1960, biology was less significant but personality traits mattered more. The average person had only two children, a new norm. Those high in openness had fewer than average, sometimes choosing to have one or none, particularly if that open person was a woman high in conscientiousness (Jokela, 2012). Her openness may have encouraged her to consider family planning, overpopulation, and nontraditional roles, and her conscientiousness made her careful to plan each birth. Context matters, always interacting with personality.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 13.1

1. What are other names for Erikson’s intimacy stage?

(1) affiliation; (2) emotional; and (3) communion

Question 13.2

2. What are the descriptions of what Freud called the need to work?

Freud said that adults need lieben und arbeiten—to love and to work. Erikson referred to generativity versus stagnation, maintaining that adults need to care for the next generation, either by raising their own children or by mentoring, teaching, and helping others.

Question 13.3

3. What are thought to be the origins of personality?

Personality begins with genes.

Question 13.4

4. Why does personality change as people grow older?

People try to shape their personality to the norms of their culture.

Question 13.5

5. How might the personality trait of openness affect people’s choice of jobs, mates, lifestyle, and neighborhood?

People who are higher in openness tend to have higher IQs and more verbal fluency. They are more likely to consider all possible options and may therefore plan and choose more wisely in all aspects of their lives.

Question 13.6

6. How might the personality trait of extraversion affect people’s choice of colleges, friends, and community involvement?

Extroverts are more active, assertive, and outgoing, and are therefore likely to attend better schools, have more friends, and be more of a leader overall.

Question 13.7

7. How might the trait of conscientiousness affect a parent’s interactions with his or her children?

Conscientious parents may be more measured with their children, instilling discipline, stability, and routine without losing their tempers or making rash decisions.