Intimacy: Connecting with Others

intimacy versus isolation

The sixth of Erikson’s stages of development. Every adult seeks close relationships with other people in order to live a happy and healthy life.

Humans are not meant to be loners. Every adult seeks to connect with other people, experiencing the crisis Erikson called intimacy versus isolation, as already explained in Chapter 11. Decades of research find that physical health and psychological well-

Variations are apparent by culture, age, and personality, with some people more connected with their friends, others with their “family of origin” (the family they were born into), and still others with their “family of choice” (mates and children). Intimacy needs can be met by each of these.

Romantic Partners

We begin our discussion of intimacy with romance. However, although sometimes the term “intimacy” implies sexual intimacy, according to Erikson and other personality theorists, intimacy includes far more than romance. Although we start with romance, we will soon discuss friends and other family members.

MARRIAGE Traditionally, the most common way that adults met intimacy needs was through marriage. Every culture and era had some sort of marriage ceremony. Historically, most adults paired off “till death did them part.”

Marriage is still a major event. Two sets of families come together, routines and rituals are enacted, the couple wears special clothes, makes public vows blessed by a respected elder, and then perhaps travels on a honeymoon, or crosses a threshold, or changes a name.

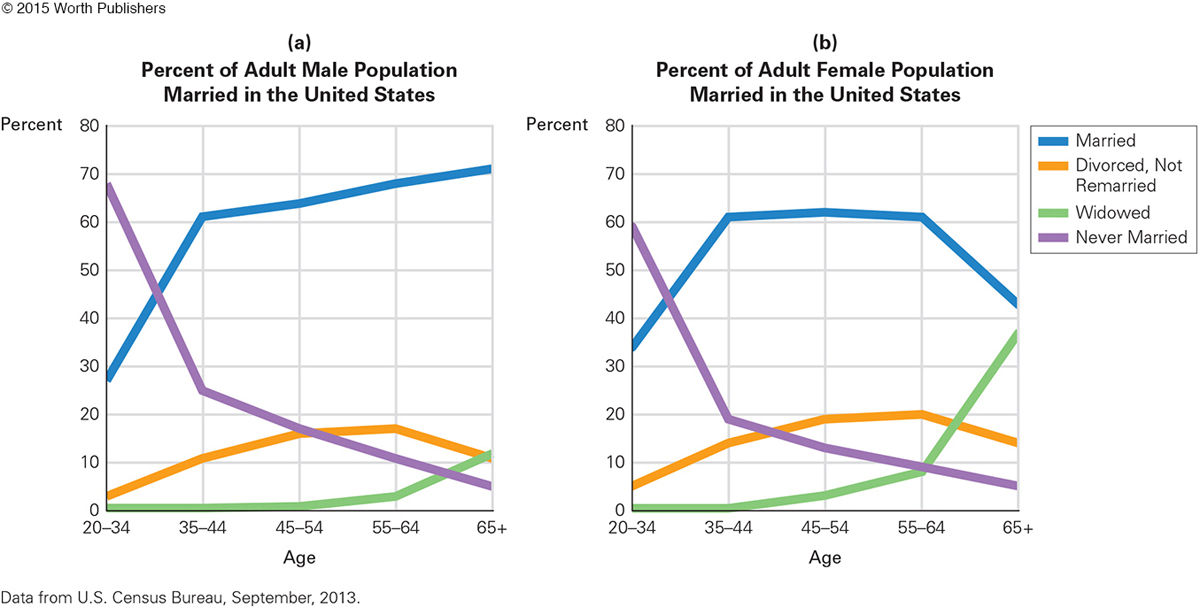

Particulars vary of course, but one trend in universal: Marriage is far less common than it once was. Cohort is crucial (see Figure 13.1).

Question 13.8

OBSERVATION QUIZ

What are the most dramatic gender differences in marriage rates?

Both married and widowed rates diverge dramatically. Probably marriage rates are the most different, since divergence begins at about age 40 and men’s rates rise while women’s fall after age 60.

The American Community Survey, which surveys a cross section of U.S. adults each year, reports that almost all U.S. residents born before 1940 married (96 percent). Of those born between 1940 and 1960, fewer (89 percent) did so, and among those born in the 1970s, 62 percent are married, including about 16 percent in a second or third marriage. Another group, about 16 percent, are separated or divorced and not remarried, and about 22 percent have never married. That trend continues: Marriage rates continue to fall.

Similar trends are found worldwide. Consider Japan. In 1950, almost every Japanese adult was married, with many marrying before age 20. Now the Japanese marry later (on average at age 30), and many (an estimated 20 percent) will never marry (Raymo, 2013).

THINK CRITICALLY: Is marriage a failed institution?

Most adults hope to marry eventually, and a majority still do, but increasing numbers do not. Marriage continues to seem desirable in theory, although not in practice. For instance, most divorced people are not disillusioned with marriage: Typically they find another mate within five years. In the United States, 40 percent of new marriages have at least one partner who has been married before (Livingston, 2014).

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Marriage and Happiness

Researchers disagree as to whether marriage leads to personal happiness or not. However, regarding the benefits to society, marriage increases the happiness of a community.

To be specific, generally adults benefit if a partner is committed to their well-

From the individual’s perspective, the consequences of marriage are more complex. A satisfying marriage improves health, wealth, and happiness, but not all marriages are satisfying (Fincham & Beach, 2010; R. Miller et al., 2013). Married people are happier, healthier, and richer on average than never-

It was once thought that men were happier in marriage and women less happy (Bernard, 1982). Suggested reasons were that women had higher expectations for marriage and thus greater disillusionment, or that women did far more housework, child care, and emotional work. However, that is changing by cohort and varies by culture (Stavrova et al., 2012).

It also varies by education, with low-

A recent meta-

Video: Marriage in Adulthood

Research on marriage and happiness comes to opposing conclusions depending on how the researchers account for factors besides the marriage. The complication is that married adults of every age tend to be wealthier, better educated, and more social than those who are not. In order to decide whether marriage itself is beneficial, those factors need to be controlled.

For example, if a married 50-

Public opinion is also conflicted. For instance, adults from different cohorts have opposite views on whether children should have married parents. More than a third (36 percent) of those under age 50 think current changes in family structure—

THINK CRITICALLY: Are current young adults forgoing happiness by avoiding marriage? Or are they averting the pain of divorce or unhappy marriage?

Research controlling for SES finds that children learn more, are sick less, and present fewer emotional problems if their parents are married—

OTHER FORMS OF ROMANTIC PARTNERSHIP Partnership does not always mean marriage, as already explored in Chapter 11. Cohabitation is particularly common in emerging adulthood. However, for adults over age 25, not only are marriage rates declining but cohabitation rates are increasing. More adults of all ages are living together, often with children. Some plan to marry; some do not.

Cohabiters vary a great deal in their plans and prospects. In general, cohabiters in eastern Europe are more likely to want to marry someday than those in western Europe (Hiekel & Castro-

Many people now prefer cohabitation to marriage. Several decades ago in 1980, about half (52 percent) of new mothers without a high school education were married. Most of the rest planned to marry someday. Thirty years later, only 17 percent of them were wed (Gibson–

A sizable number of adults have found a third way (neither marriage nor cohabitation) to meet their intimacy needs with a steady romantic partner. They are living apart together (LAT). They have separate residences, but especially when the partners are over age 30, they function as a couple for decades, sexually faithful, vacationing together, and so on (Duncan & Phillips, 2010).

Financial patterns are a particular issue for LAT couples. Most married couples pool their money; many cohabiting couples do not (Hamplová et al., 2014). LAT couples struggle with this aspect of their relationship, with the women particularly wanting to pay their own way (Lyssens-

Every couple’s decision to marry, cohabit, or LAT is influenced by their families and cultures. Children are influential. Cohabiters who have had children together are more likely to marry than those without, especially when the children start school. Likewise, married couples sometimes stay together for the children, and sometimes one parent leaves a violent mate to protect the children. As for LAT couples, many older parents maintain separate households because they do not want to upset their grown children (de Jong Gierveld & Merz, 2013).

PARTNERSHIPS OVER THE YEARS The four boxes that questionnaires typically provide—

My whole life I have been searching for love. At a personal level, after a number of false starts, I have found it. In my research—

[Sternberg, 2013a, p. 98]

Since 1986, Sternberg has studied three aspects of love: passion, intimacy, and commitment. That triad continues to be explored by many other researchers (Sternberg & Weis, 2006; Sumter et al., 2013; Fletcher et al., 2015). Among twenty-

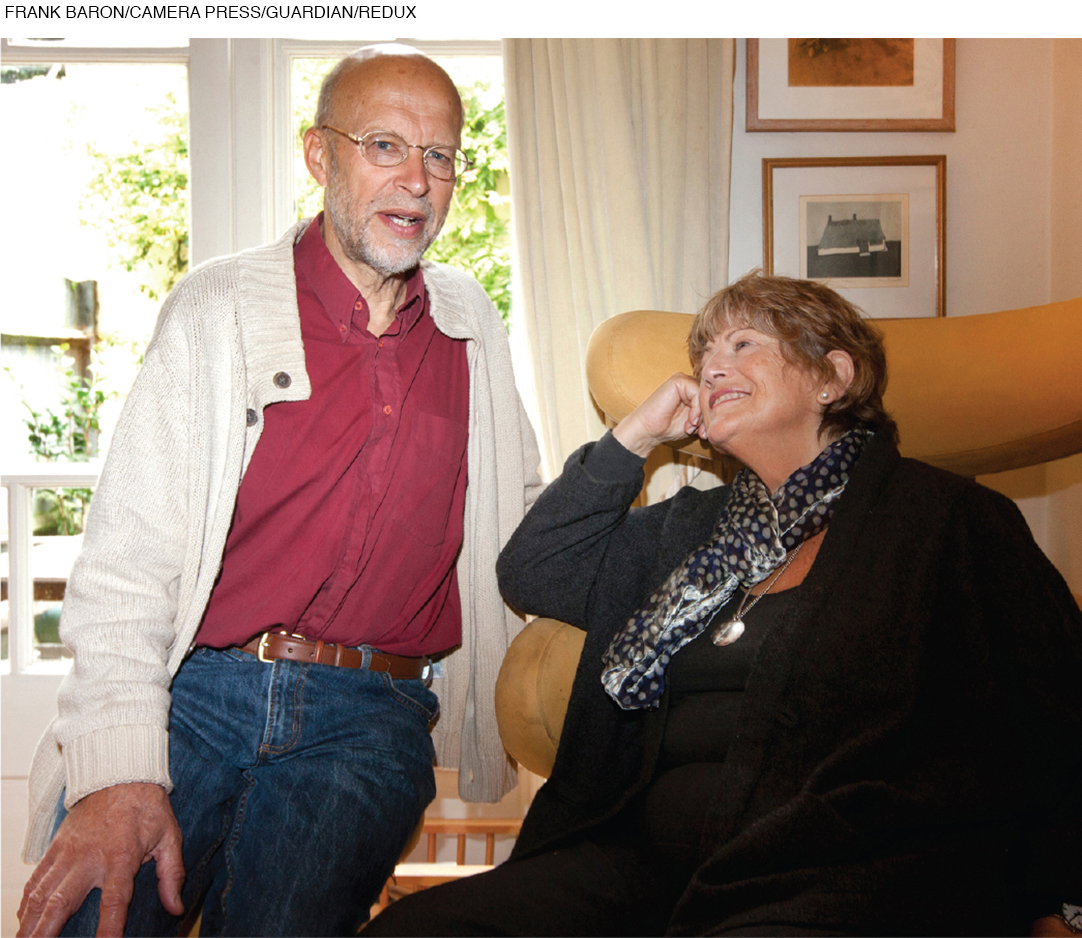

A wealth of research finds that for most adults mutual commitment is the most crucial of the three. A long-

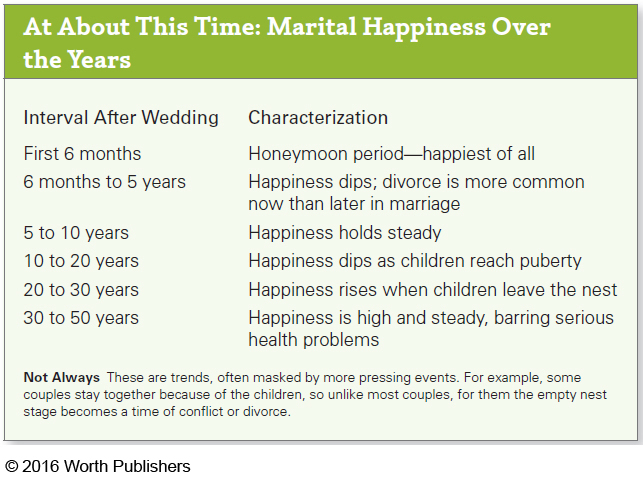

The passage of time also makes a difference. In general, the honeymoon period tends to be happy, but frustration with a partnership increases as conflicts—

Remember, however, that averages obscure many differences of age, ethnicity, personality, and circumstances. In the United States, Asian Americans are least likely to divorce and African Americans are most likely to do so. These ethnic differences are partly cultural and partly economic, making any broad effort to encourage marriage for everyone doomed to disappoint the politicians, social workers, and individuals involved (Johnson, 2012).

Education matters too: College-

As already noted, the divorce risk falls with age, but older couples are divorcing at increasing rates. In 1990, 8 percent of divorces were of people age 50 and older; in 2010, 25 percent of divorcees were that old, often in marriages that had lasted for decades (Brown & Lin, 2013).

empty nest

The time in the lives of parents when their children have left the family home to pursue their own lives.

Contrary to outdated impressions, the empty nest—when parents are alone again after the children have left—

Of course, time does not fix every relationship. Economic stress causes marital friction no matter how many years a couple has been together (Conger et al., 2010). Under the weight of major crises—

Remember the concept of linked lives from Chapter 11. Couples increasingly link their lives over time, with marital satisfaction connected to what they have achieved together and how happy the other one is (Carr et al., 2014). Children suffer or benefit accordingly.

GAY AND LESBIAN PARTNERS Almost everything just described applies to gay and lesbian partners as well as to heterosexual ones (Biblarz & Savci, 2010; Cherlin, 2013; Herek, 2006). Some same-

Others are conflicted: Problems of finances, communication, and domestic abuse resemble those in heterosexual marriages. As the U.S. Supreme Court recently confirmed, love between partners is the crucial bond. As with every romance, when love fades, problems arise.

The similarity of all partnerships was apparent in a study of alcohol abuse in romantic couples. Researchers expected that the stress of minority status among the gay and lesbian couples would increase the rate of alcohol use disorder. That was not what the data revealed. Instead, the crucial variable was whether the couple was married or cohabiting. For both same-

Another finding is relevant for all partnerships—

In a study of married gay couples in Iowa, one man decided to marry because of his mother: “I had a partner that I lived with . . . And I think she, as much as she accepted him, it wasn’t anything permanent in her eyes” (Ocobock, 2013, p. 196). Another man wrote about his father: “[He] told us how proud of us he was that we were taking this step, and now he didn’t have three sons, he had four sons, and it was enough to make you cry” (p. 197).

In this study, most family members were supportive, but some were not—

Some research says divorce is less common for same-

DIVORCE AND REMARRIAGE Throughout this text, developmental events that seem isolated, personal, and transitory are shown to be interconnected and socially constructed, with enduring consequences. Relationships never improve or end in a vacuum; they are influenced by the macrosystem and exosystem. For example, a study of many nations found that the happiness as well as the likelihood of separation of married and cohabiting couples were powerfully influenced by national norms (Wiik et al., 2012).

Divorce occurs because at least one partner believes that he or she would be happier without the spouse, a conclusion reached fairly often in the United States: Since 1980, almost half as many divorces or permanent separations have occurred as marriages. (More than one-

Divorce is a process that begins long before the official decree. Typically, happiness dips in the months before a divorce and then increases after official separation (Luhmann et al., 2012). People divorce because some part of the marriage has become difficult to endure, and they are relieved to be free of it. Over the years, however, reduced income, lost friendships, and weaker relationships with offspring are common (Kalmijn, 2010; Mustonen et al., 2011).

Family problems arise from divorce not only with children (usually custodial parents become stricter and noncustodial parents become distant) but also with other relatives. The divorced adult’s parents may be financially supportive but not emotionally supportive. Some married adults have good relationships with their in-

Intimacy needs are jeopardized when couples separate. Sometimes divorced adults confide in their children, explaining why the other spouse was difficult to live with. That may help the adults but not the children. Even if adults avoid that trap, children need extra stability and understanding just when the parents are consumed by their own emotions (H. S. Kim, 2011).

Some research finds that women suffer from divorce more than men (their income, in particular, is lower), but men’s intimacy needs are especially at risk. Many husbands rely on their wives for companionship and social interaction; they are unaccustomed to inviting friends over or chatting on the phone. Divorced fathers are often lonely, alienated from their adult children and grandchildren.

Given the loss of intimacy, it is not surprising that both former partners in a severed relationship attempt to reestablish friendships and often resume dating, with men particularly likely to remarry. Remarriage is more common as SES rises and less common among those with custodial children. Ethnicity is also a factor; divorced African American mothers, especially those with less than a high school education, rarely remarry (McNamee & Raley, 2011).

Initially, remarriage restores intimacy, health, and financial security. For fathers, bonds with stepchildren or with a new baby may replace strained relationships with their children from the earlier marriage, a benefit for the men but not for the children (Noël-

Divorce is never easy, but the negative consequences just explained are not inevitable. If divorce ends an abusive, destructive relationship (as it does about one-

On average, divorce causes long-

Friends and Acquaintances

social convoy

Collectively, the family members, friends, acquaintances, and even strangers who move through the years of life with a person, all aging together.

Each person is part of a social convoy. The term convoy originally referred to a group of travelers in hostile territory, such as the pioneers in ox-

As people move through life, their social convoy functions as those earlier convoys did, a group of people who provide “a protective layer of social relations to guide, socialize, and encourage individuals as they move through life” (Antonucci et al., 2001, p. 572).

FRIENDSHIP OVER THE YEARS Friends are part of the social convoy; they are chosen for the traits that make them reliable fellow travelers. Mutual loyalty and aid characterize friendship: An unbalanced friendship (one giving and the other taking) often ends because both parties are uncomfortable.

Of course, sometimes a friend needs care and cannot reciprocate at the time, but it is understood that later the roles may be reversed. Friends provide practical help and useful advice when serious problems—

Adults consult their friends about everyday issues such as how to get children to eat their vegetables, whether to remodel or replace the kitchen cabinets, when to ask for a raise, why a particular acquaintance is unreasonable. Such issues are best discussed with another person of the same age, gender, and situation—

Friendships tend to improve over the decades of adulthood. As adults grow older, they tend to have fewer friends overall, but they keep their close friends and nurture those relationships (English & Carstensen, 2014).

Friendship aids physical and mental health throughout life (Bowers & Lerner, 2013). Friends encourage one another to eat better, to quit smoking, to exercise, and so on. The reverse is also true: If someone gains weight over the years of adulthood, his or her best friend is likely to do so as well. In fact, although most friendships last for decades, conflicting health habits may end a relationship (O’Malley & Christakis, 2011). For instance, a chain smoker and a friend who quit smoking are likely to part ways.

If an adult has no close and positive friends, health suffers (Couzin, 2009; Fuller-

ACQUAINTANCES In addition to friends, people have hundreds of casual acquaintances who provide information, support, social integration, and new ideas (Fingerman, 2009). With age, the number of peripheral friends usually decreases (English & Carstensen, 2014) because of personal choice and because of social context. For example, retirement can sever work friendships.

As in all of adulthood, individual variation—

consequential strangers

People who are not in a person’s closest friendship circle but nonetheless have an impact.

Some acquaintances—

Among the consequential strangers in an adult’s life might be:

Other people who commute daily on the same bus or train

A barber or beautician if adults regularly get their hair cut

A street vendor or store owner who is patronized daily

A friend of a friend

A friend’s family member

A consequential stranger may even be literally a stranger: someone who sits next to you on an airplane, or directs you when you are lost, or gives you a seat on the bus. Not all such people are consequential. Some cultures and contexts make such strangers part of the informal social support; others discourage talking to strangers.

Whether called acquaintances or strangers, such people are unlike the inner circle in that many are not of the same religion, ethnic group, age, or political views. That diversity is one reason they may be consequential, particularly in current times (Fingerman, 2009).

THINK CRITICALLY: Does the rising divorce rate indicate stronger or weaker family links?

Consequential strangers need not be notably helpful. Although encouragement is welcome, simply having contact with next-

For truly reliable support, most people turn to family, as now explained.

Family Bonds

Family links span generations and endure over time, even more than friendship networks or romantic partnership. Childhood connections (or lack of them) influence social relationships in adulthood. For example, one’s parents’ marriage, divorce, and birth patterns affect adult’s behavior.

This does not always mean that adults do what their own parents did: Sometimes the opposite occurs. One of my students complained about her life as one of sixteen children; she had only one child, and she said that was enough. As she explained this to the class, it seemed apparent that her choice was in reaction to her childhood.

The power of family experiences was documented in data from all the twins in Denmark. They married less often than single-

More generally, family members have linked lives, which means that events or conditions that affect one family member affect them all (e.g., Wickrama et al., 2013). This is obvious positive events—

In another example, if a man goes to prison, every member of his family is affected (J. Murray et al., 2012). If he is married, and the marriage endures (divorce is particularly common when a man is jailed), one study found that upon release wives tend to report much less satisfaction with the marriage than husbands do (Turney, 2015). Obviously, the wife is linked to the husband’s experiences.

PARENTS AND THEIR ADULT CHILDREN Of course, a crucial part of family life for many adults is bearing and raising young children, a topic discussed soon as part of generativity. Here we focus on family bonds that can meet adult intimacy needs, specifically on the relationship between parents and their adult children. Such relationships are often a source of companionship, support, and affection for both generations of adults.

At the outset, we should explain that this adult–

If income allows, most adults seek to establish their own households. A study of 7,578 adults in seven nations found that physical separation did not weaken family ties. Indeed, intergenerational relationships seem to be strengthened, not weakened, as adult children lived apart from their parents (Treas & Gubernskaya, 2012). Between parents and adult children, “the intergenerational support network is both durable and flexible” (Bucx et al., 2012, p. 101), recently including Skype, smartphones, and jets to minimize distance.

That flexibility is apparent worldwide. When adult children have serious financial, legal, or marital problems, parents try to help, with the particular form of help dependent on the circumstances. For example, if a divorced child has custody of children, the grandparents (usually middle-

The recent economic recession led to “boomerang” children, adults who live with their parents for a while. In the United States, in 1980 only 11 percent of 25-

All the research shows that parents provide more financial and emotional support to their adult children than vice versa. Although such support is often needed and welcome, financial subsidies to adult children who are no longer in college correlate with symptoms of depression in the offspring (Johnson, 2013).

For middle-

SIBLINGS In adolescence and early adulthood, brothers and sisters often fight or keep their distance. Then in adulthood, siblings become closer. Not always, of course. With adulthood often comes “marriage and childbearing, both of which have the potential to enhance closeness in sibling relationships or exacerbate previous difficulties” (Conger & Little, 2010, p. 89). Parenthood often reconnects siblings, partly because children benefit from relationships with aunts, uncles, and cousins.

One factor that decreases sibling closeness is parental favoritism of one adult child over another. Particularly when fathers show favoritism, both favored and unfavored adults are likely to be distressed (Jensen et al., 2013).

Generally, conflicts that arise in childhood (almost inevitable with shared rooms, computers, schools, parents, and so on) are moot in adulthood. That allows adults to differ amicably in habits or lifestyles, releasing them to share information and concerns.

Sometimes sibling closeness is assumed by the culture. In several South Asian nations, brothers are obligated to bestow gifts on their sisters, who in turn are expected to cook for and nurture their brothers (Conger & Little, 2010). Encouraging siblings to care for one another helps satisfy their intimacy needs.

Such interdependence may impede individual growth, but it reduces poverty and strengthens family bonds. Another cause of stronger bonds may be government programs such as health care, senior residences, and child care. When adults do not argue over material needs, they are likely to seek emotional intimacy.

FICTIVE KIN Most adults seek to maintain connections with family members, sometimes traveling great distances to attend weddings, funerals, and holidays. The power of this link is apparent when we note that, unlike friends, family members may be on opposite sides of political or lifestyle issues. Even radically different views do not usually keep them apart.

fictive kin

People who become accepted as part of a family who have no genetic or legal relationship to that family.

Sometimes, however, adults avoid their blood relatives because they find them toxic—

Fictive kin can be a lifeline to those adults who are rejected by their original family (perhaps because of their sexual orientation) or are isolated far from home (perhaps immigrants) or are changing their family habits (such as stopping addiction) (Ebaugh & Curry, 2000; Heslin et al., 2011; E. Kim, 2009; Muraco, 2006). The need for fictive kin reinforces a general theme: Adults benefit from kin, fictive or not.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 13.9

1. What needs do long-

Long-

Question 13.10

2. How and why does marital happiness change from the wedding to old age?

The honeymoon period tends to be the happiest time, but soon frustration increases as conflicts arise. Partnerships tend to be less happy after the first child is born, and again when children reach puberty. Divorce risk rises and then falls during these times. Happiness rises when children leave the nest and happiness continues to be high and steady after that, barring serious health problems.

Question 13.11

3. How do same-

Just like heterosexual couples, some same-

Question 13.12

4. What are the usual consequences of divorce?

Consequences of divorce often include reduced income, family problems, lost friendships, and weakened relationships with one’s children. That said, if the divorce ends an abusive or difficult situation, it could improve life for at least one adult and for the children.

Question 13.13

5. Why do remarriages have a higher divorce rate than first marriages?

Personality tends to change only slightly over the lifespan; therefore, people who were chronically unhappy in their first marriage may also become unhappy in their second. In addition, if there are stepchildren, they add unexpected stresses, and stepparents may have difficulty letting the spouse’s former mate continue to care for their own children.

Question 13.14

6. Why would people choose to live apart together (LAT)?

A couple’s decision to LAT is influenced by their families and cultures. For instance, cohabiters who have had children together are more likely to marry than those without, especially when the children start school. Many older parents maintain separate households because they do not want to upset their grown children. Finances also play a part; while most married couples pool their money, many cohabiting couples do not. LAT couples struggle with this aspect of their relationship, with the women particularly wanting to pay their own way.

Question 13.15

7. Why do people need a “social convoy”?

A social convoy provides a protective layer of social relationships that guide, encourage, and socialize the individual.

Question 13.16

8. What roles do friends play in a person’s life?

Friends are chosen for the traits that make them reliable fellow travelers through life. Mutual loyalty and aid are expected from friends. Friends offer companionship, information, and laughter in daily life. Unlike family members, if friends are not supportive, the relationship ends.

Question 13.17

9. What are the differences between friends and consequential strangers?

Individuals choose their friends and develop an intimate connection with them. Consequential strangers are neighbors, coworkers, store clerks, local police officers, or members of a religious or other community group. A consequential stranger is not in a person’s closest convoy but is one who nonetheless has an impact on the person’s experience through at least one, and often repeated, interactions. Consequential strangers include people of diverse religions, ethnic groups, ages, and political opinions without the shared values, lifestyles, and background that are often the glue that keeps friendships close.

Question 13.18

10. What is the usual relationship between adult children and their parents?

The relationship between adult children and their parents becomes stronger, not weaker, as adult children live apart from their parents. The intergenerational support network is both durable and flexible. Due to the economic recession, more adult children 25 to 34 years old have been living with their parents than during the last major recession in 1980. Most of these modern young adults report feeling comfortable staying with their parents when they needed to.

Question 13.19

11. What usually happens to sibling relationships over the course of adulthood?

Marriage and childbearing in adulthood typically enhance closeness in sibling relationships. Parents want their children to know their aunts, uncles, and cousins, and that reduces sibling distance. Furthermore, adulthood frees siblings from forced cohabitation and rivalry, allowing them to differ without fighting.

Question 13.20

12. Why do people have fictive kin?

Some adults may become fictive kin in another family because they have been rejected by their original family, are far from home, or are changing their habits. Adults benefit from kin, fictive or not.