Older and Wiser?

You have learned that most older adults maintain adequate intellectual power. Only a minority suffer from a major neurocognitive disorder.

The life-

Erikson and Maslow

Both Erik Erikson and Abraham Maslow were interested in the elderly, interviewing older people to understand their views. Erikson wrote his final book, Vital Involvement in Old Age (Erikson et al., 1986/1994), when he was in his 90s. It was based on responses from other 90-

Erikson found that in old age many people gained interest in the arts, in children, and in the human experience as a whole. His eighth stage, integrity versus despair, marks the time when life comes together in a “re-

self-

The final stage in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, characterized by aesthetic, creative, philosophical, and spiritual understanding.

Maslow maintained that older adults are more likely than younger people to reach what he originally thought was the highest stage of development, self-

The stage of self-

This seems characteristic of many of the elderly. Jeanne Calment, the French woman who lived the maximum (122), was notably happy. She said, “I will die laughing.”

Learning Late in Life

Many people have tried to improve the intellectual abilities of older adults by teaching or training them in various tasks (Lustig et al., 2009; Stine-

Almost all researchers have accepted the conclusion that people younger than 80 can advance in cognition if the educational process is carefully targeted to their motivation and ability.

For instance, in one study in southern Europe elderly people were taught memory strategies and attended motivational discussions to help them understand why and how memory was useful. Their memory improved compared to a control group, and the improvements were still evident 6 months later (Vrani´c et al., 2013).

How about those over age 80? The older people are, the harder it is for them to master new skills and then apply what they know (Stine-

Let’s return to the question of cognitive gains in late adulthood. In many nations, education programs have been created for the old, called Universities for the Third Age in Europe and Australia, and Road Scholar (formerly Exploritas) in the United States. Classes for seniors must take into account their needs and motivations: Some want intellectually challenging courses and others want practical skills (Villar & Celdrán, 2012). When motivated, older adults can learn.

AESTHETIC SENSE AND CREATIVITY Robert Butler was a geriatrician responsible for popularizing the study of aging in the United States. He coined the word ageism and wrote a book, Why Survive?: Being Old in America, first published in 1975. Partly because his grandparents were crucial in his life, Butler understood that the elderly need society to recognize their potential.

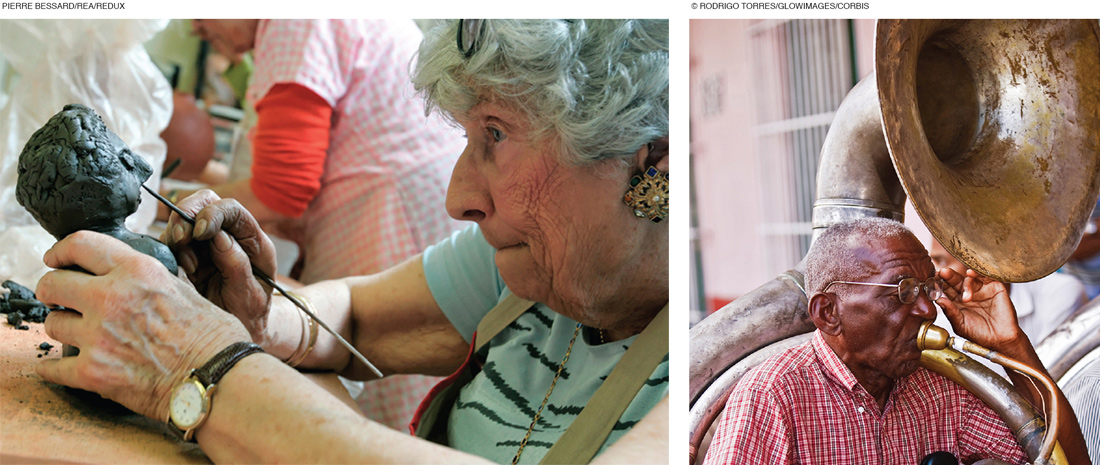

Butler explained that “old age can be a time of emotional sensory awareness and enjoyment” (Butler et al., 1998, p. 65). For example, some of the elderly take up gardening, bird-

Many well-

In a study of extraordinarily creative people, almost none felt that their ability, their goals, or the quality of their work had been much impaired by age. The leader of that study observed, “Now in their seventies, eighties, and nineties, they may lack the fiery ambition of earlier years, but they are just as focused, efficient, and committed as before” (Csikszentmihalyi, 2013, p. 207).

But an older artist does not need to be extraordinarily talented. Some of the elderly learn to play an instrument, and many enjoy singing. In China people gather spontaneously in public parks to sing together. The groups are intergenerational—

Music and singing are often used to reduce anxiety in those who suffer from neurocognitive impairment, because the ability to appreciate music is preserved in the brain when other functions fail (Ueda et al., 2013). Many experts believe that creative activities—

life review

An examination of one’s own role in the history of human life, engaged in by many elderly people. This can be written or oral.

It may be that everyone can become a writer or storyteller in old age. In the life review, elders provide an account of their personal journey by writing or telling their story. They want others to know their history, not only their personal experiences but also those of their family, cohort, or ethnic group. According to Robert Butler:

We have been taught that this nostalgia represents living in the past and a preoccupation with self and that it is generally boring, meaningless, and time-

[Butler et al., 1998, p. 91]

Hundreds of developmentalists, picking up on Butler’s suggestions, have guided elderly people in self-

WISDOM It is possible that “older adults . . . understand who they are in a newly emerging stage of life and discovering the wisdom that they have to offer” (Bateson, 2011, p. 9). A massive international survey of 26 nations from every corner of the world found that most people everywhere agree that wisdom is a characteristic of the elderly (Löckenhoff et al., 2009).

Contrary to these wishes and opinions, most objective research finds that wisdom does not necessarily increase with age. Starting at age 25 or so, some adults of every age are wise, but most, even at age 80, are not (Staudinger & Glück, 2011).

But what is wisdom? Each culture and each cohort has its own concept, with fools sometimes seeming wise (as in the works of Shakespeare) and those who are supposed to be wise sometimes acting foolishly (provide your own examples). Older and younger adults differ in how they make decisions; one interpretation of such differences is that the older adults are wiser, but not every younger adult would agree (Worthy et al., 2011).

One summary describes wisdom as an “expert knowledge system dealing with the conduct and understanding of life” (Baltes & Smith, 2008, p. 58). Several factors just mentioned, including the ability to put aside one’s personal needs (as in self-

If this is true, the elderly may have an advantage in developing wisdom, particularly if they have: (1) dedicated their lives to the “understanding of life,” (2) learned from their experiences, and (3) become more mature and integrated (Ardelt, 2011, p. 283). That may be why popes and Supreme Court justices are usually quite old.

Similarly, the author of a detailed longitudinal study of 814 people concludes that wisdom is not reserved for the old, and yet humor, perspective, and altruism increase over the decades, gradually making people wiser. He then wrote:

To be wise about wisdom we need to accept that wisdom does—

[Vaillant, 2002, p. 256]

In Video: Portrait of Aging: Bill, Age 99, one man shares his secret to longevity.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 14.38

1. How can older people help to improve their own cognitive abilities?

Through cognitive skills training, older adults sometimes learn cognitive strategies and skills and maintain that learning if the strategies and skills are frequently used.

Question 14.39

2. Why might older people become more creative, musical, and spiritual than before?

In a study of extraordinarily creative people, almost none felt that their ability, their goals, or the quality of their work had been much impaired by age. Old age can be a time of emotional sensory awareness and enjoyment.

Question 14.40

3. What educational opportunities are available for the elderly?

In many nations, education programs have been created for the old, called Universities for the Third Age in Europe and Australia, and Road Scholar (formerly Exploritas) in the United States. Elderly people can also experience “emotional sensory awareness and enjoyment” through gardening, bird-

Question 14.41

4. What happens with creative ability as people grow older?

Many well-

Question 14.42

5. What is the purpose of the life review?

Through a life review, elderly people provide an account of their personal journey by writing or telling their story. They want others to know their history, not only their personal experiences but also those of their family, cohort, or ethnic group.

Question 14.43

6. Why are scientists hesitant to say that wisdom comes from age?

Contrary to these wishes and opinions, most objective research finds that wisdom does not necessarily increase with age. Starting at age 25 or so, some adults of every age are wise, but most, even at age 80, are not. An underlying research quandary is that a universal definition of wisdom is elusive.