Activities in Late Adulthood

As you read, most of the research finds that active elders live longer and more happily than inactive ones. Elders themselves bear this out. Most of them wish they had more time to do all they want to do, and they enjoy their active, busy lives.

This might surprise young college students, who see few gray hairs at sports events, political rallies, job sites, or midnight concerts. But most of the elderly are far from inactive; it’s just that their activities differ from the young. We now present specifics.

Working

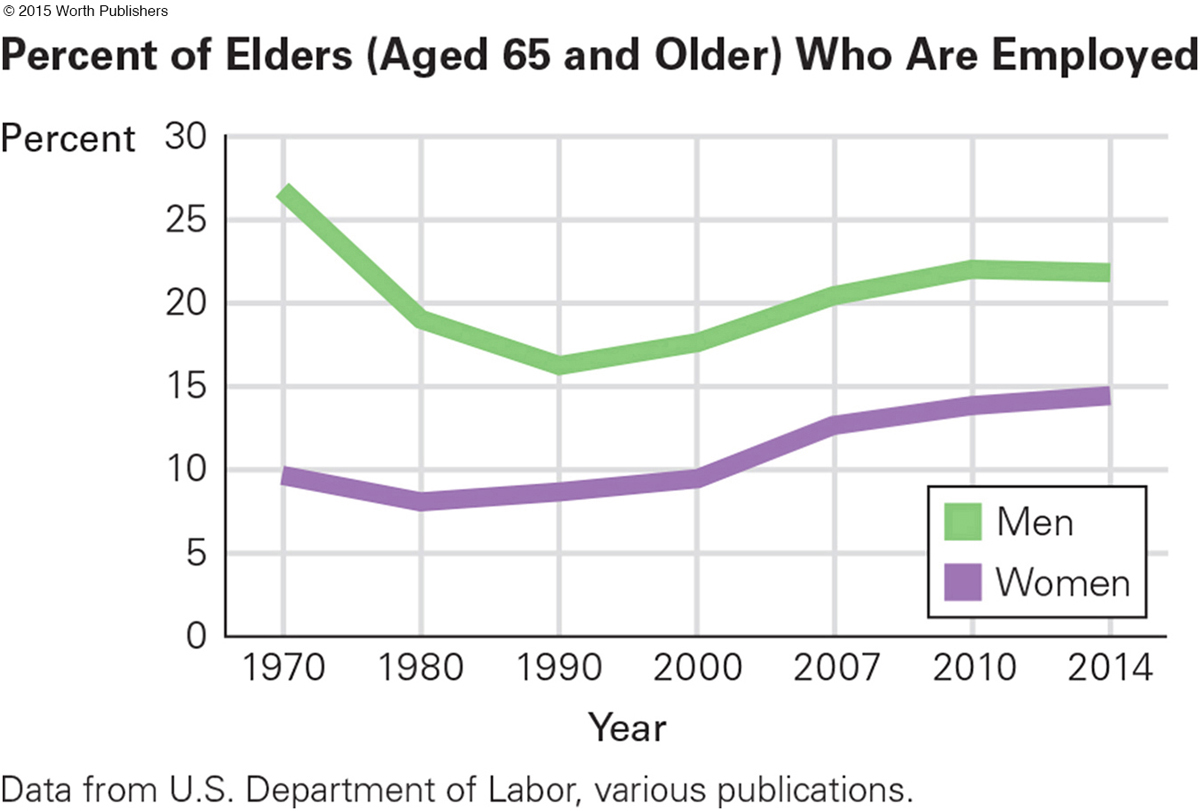

A significant proportion of the elderly continue working, because work provides social support and status. Many elders are reluctant to give that up (see Figure 15.4). Others retire from their paid jobs but nonetheless remain productive.

PAID WORK Employment history affects current health and happiness of older adults (Wahrendorf et al., 2013). Those who lost their jobs because of structural changes (a factory closing, a corporate division eliminated) are, decades later, less likely to be in good health than those who chose to retire (Schröder, 2013). Income matters as well: Those who have sufficient savings and an adequate pension are much more likely to enjoy old age.

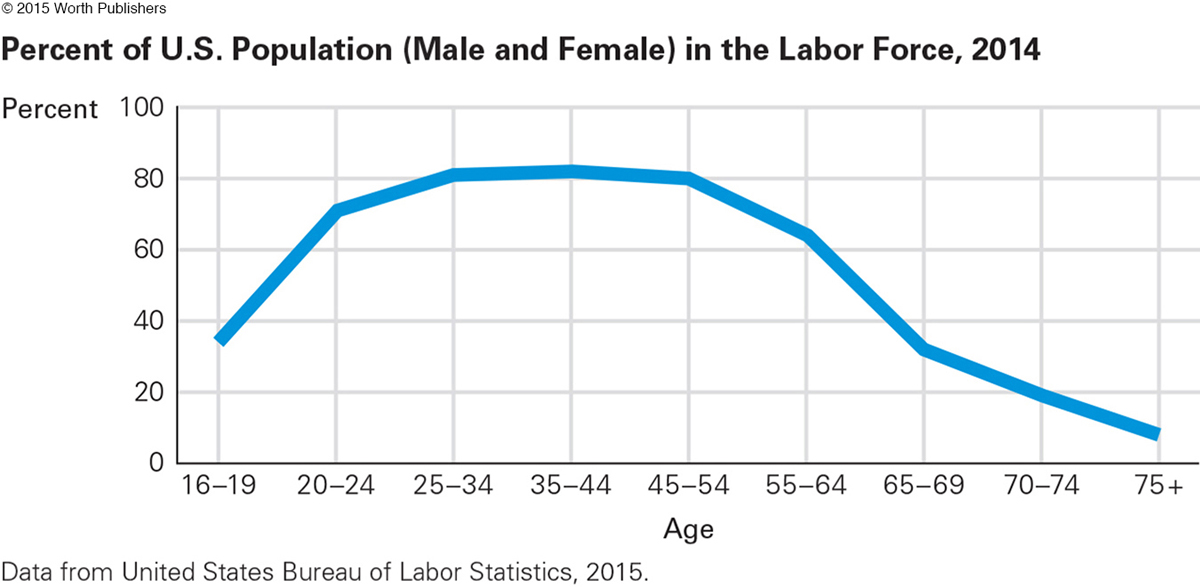

About one in three older adults keeps working after age 65 (see Figure 15.5). The main reason is to keep their paychecks. Some private pensions have been eliminated, and many governments are reducing national pensions. Thus, the elderly stay in the workforce because of the overall economic structure—

For example, in 2010 the French raised the pension age from 60 to 62, a move reversed in 2012 for those who have worked at least 40 years. In the United States, full Social Security benefits begin at age 65 for those born before 1938, but now those born after 1959 must be age 67 to receive their full benefits.

Nonunionized, low-

RETIREMENT Adequate income and poor health are the two primary reasons some people retire before age 60 (Alavinia & Burdorf, 2008); family concerns are also influential. Remember generativity? Adults try to balance family and work needs, and therefore parenthood and grandparenthood affect retirement age. To be specific, fathers tend to work a little longer than other men; mothers tend to retire a little earlier (Hank & Korbmacher, 2013). Being a caregiving grandmother is also a reason for earlier retirement (Hochman & Lewin-

In Video: Retirement, several older adults discuss how they remain active and engaged despite being retired.

Many retirees hope to work part time or become self-

Of course, if retirement is precipitated by poor health or fading competence, it correlates with illness, but the idea that retirement causes illness seems more myth than fact. If quitting work leads to disengagement, it results in mental decline (Mazzonna & Peracchi, 2012; Rohwedder & Willis, 2010), but that is far from inevitable. When retirees voluntarily leave their jobs and then engage in activities and intellectual challenges, as many do, they become healthier and happier than they were before (Coe & Zamarro, 2011).

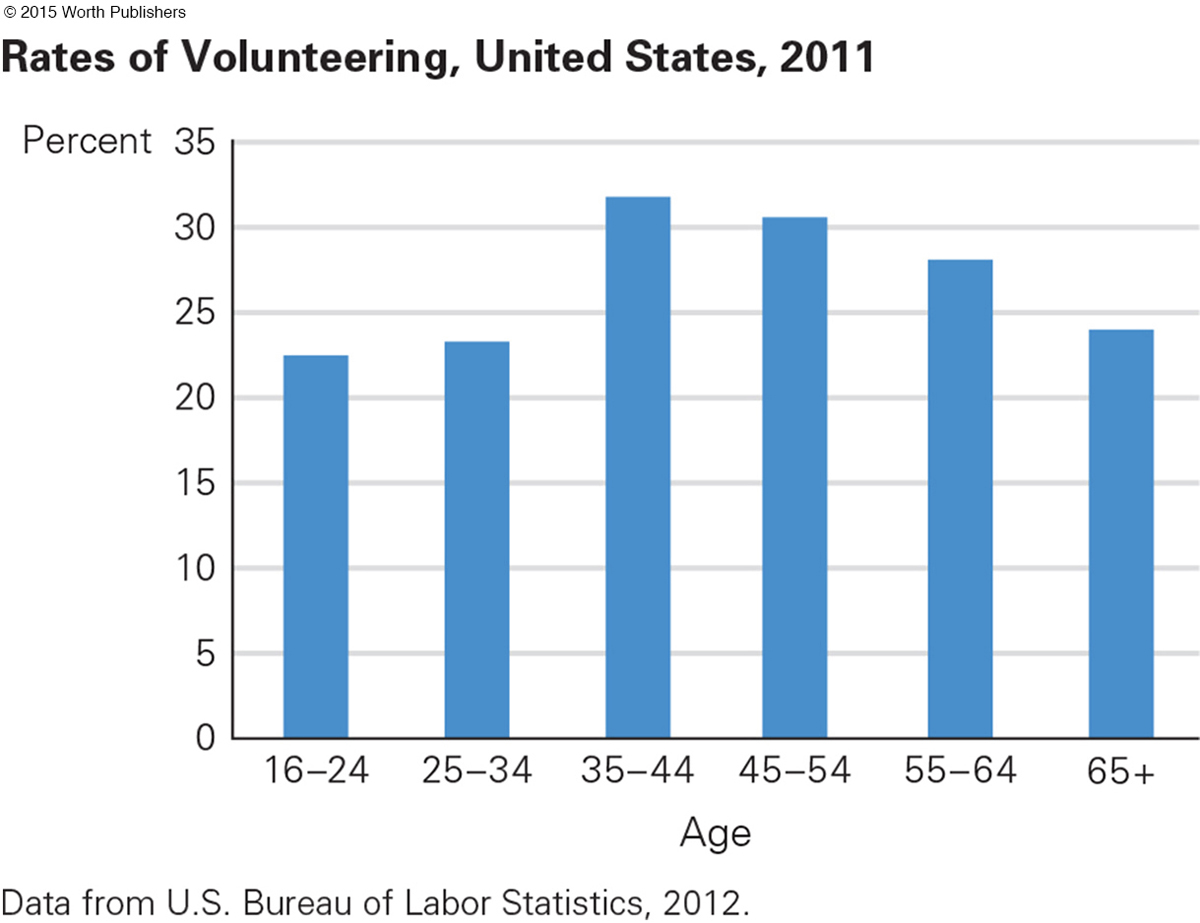

VOLUNTEER WORK Volunteering offers some of the benefits of paid employment (generativity, social connections). Longitudinal as well as cross-

As self theory would predict, volunteer work attracts older people who always were strongly committed to their community and had more social contacts (Pilkington et al., 2012). Beyond that, volunteering itself protects health, even for the very old. A meta-

Culture or national policy affects volunteering: Nordic elders (in Sweden and Norway) volunteer more often than their Mediterranean counterparts (in Italy and Greece). People in the United States are more likely to volunteer than people in Germany, partly because much of U.S. volunteering occurs with religious organizations, which are less popular in Germany.

Researchers in Germany hypothesized that the elderly needed encouragement and suggestions (Warner et al., 2014). Accordingly, they provided a two-

The attendees already expressed interest in “active retirement,” but a third of them had done no volunteering at all. Six weeks later, volunteering among the attendees doubled. Specifically, some non-

The conclusion of that study is that elders benefit from encouragement and suggestions. Half of all volunteers of any age do so because someone asked them. Knowing someone else who volunteers is also an incentive. Being married to a volunteer increases volunteering.

THINK CRITICALLY: Can you think of another definition of volunteering that would increase the rate for elderly adults?

Overall, data on volunteering reveal two areas of concern, however. First, older retirees are less likely to volunteer than middle-

Home Sweet Home

One of the favorite activities of many retirees is caring for their own homes and taking care of their own needs. Typically, both men and women do more housework and meal preparation (less fast food, more fresh ingredients) after retirement (Luengo-

Both sexes do yard work, redecorate, build shelves, hang pictures, rearrange furniture. One study found that husbands did much more housework and yard work when they retired, but wives did not reduce their work proportionally when husbands became more helpful around the house. Apparently, couples found more things to do when they had more time to do them (Leopold & Skopek, 2015).

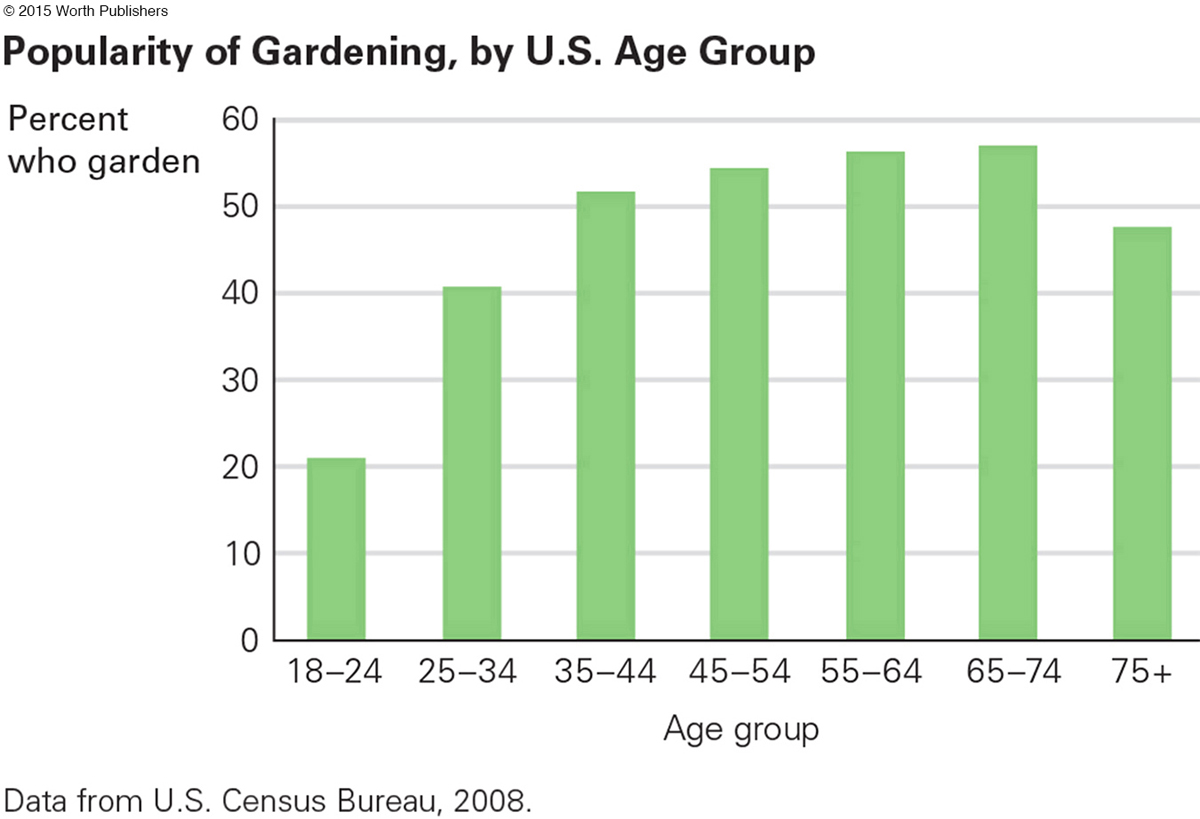

Gardening is particularly popular: More than half the elderly in the United States do it (see Figure 15.7). Tending flowers, herbs, and vegetables is productive because it involves both exercise and social interaction (Schupp & Sharp, 2012).

age in place

To remain in the same home and community in later life, adjusting but not leaving when health fades.

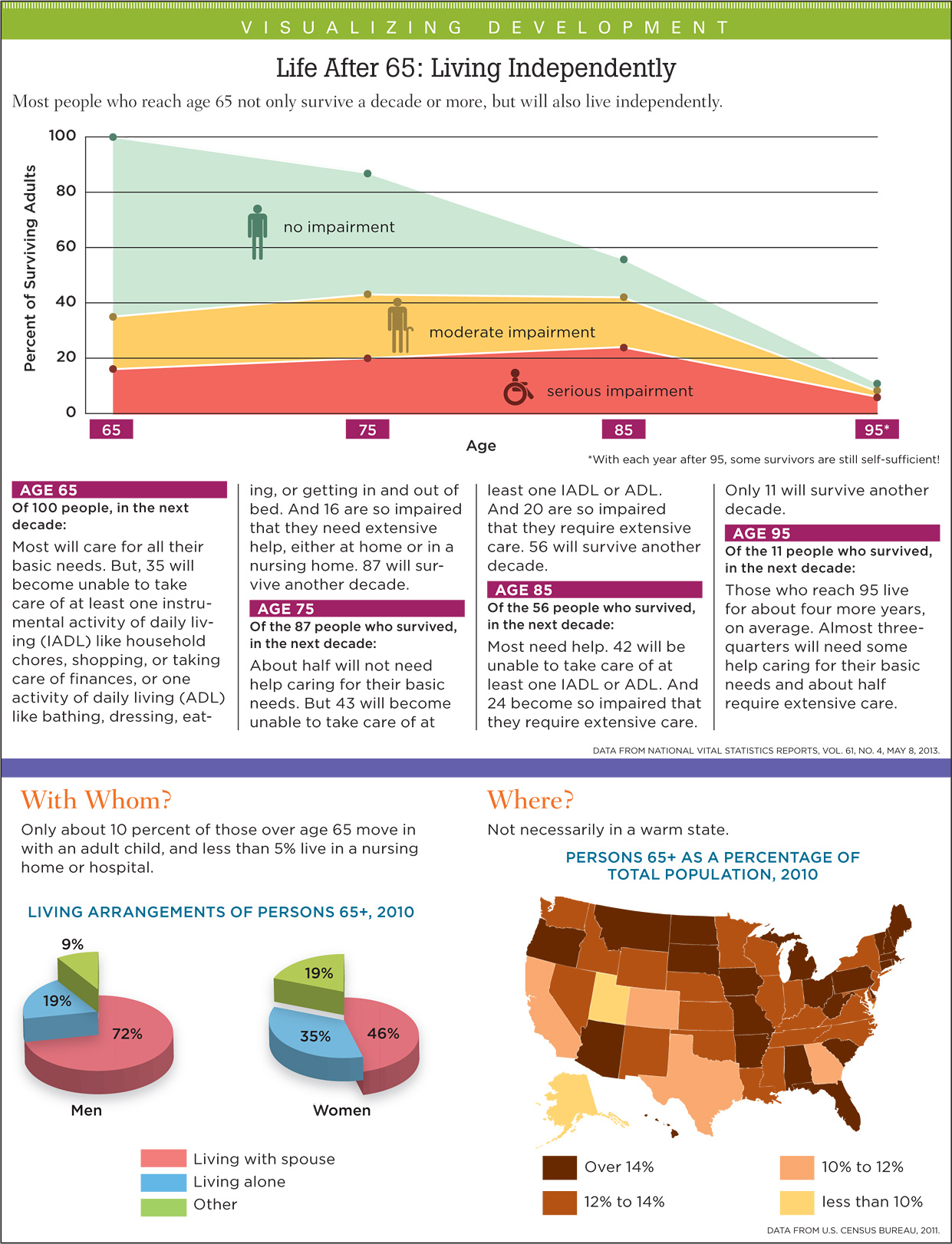

In keeping up with household tasks and maintaining their property, almost all older people—

Except for those immigrants, most of those who move do not go far. They may find a smaller apartment with an elevator and less upkeep, but Americans rarely uproot themselves to another city or state unless they already know people there. That is wise: Elders fare best surrounded by long-

The preference for aging in place is evident in state statistics. Of the 50 states, Florida has the largest percentage of people over age 65, many of whom moved there not only for the climate but also because they already knew people there. The next three states highest in proportion of population over age 65 are Maine, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania, all places where older people have aged in place.

Fortunately, aging in place has become easier. One successful project sent a team (a nurse, occupational therapist, and handyman) to vulnerable aged adults, most of whom became better able to take care of themselves at home, avoiding institutions (Szanton et al., 2015). Elders themselves use selective optimization with compensation as they envision staying in their homes despite age-

About 4,000 consultants are now certified by the National Association of Homebuilders to advise about universal design, which includes making a home livable for people who find it hard to reach the top shelves, to climb stairs, to respond to the doorbell. Non-

naturally occurring retirement community (NORC)

A neighborhood or apartment complex whose population is mostly retired people who moved to the location as younger adults and never left.

Assistance to allow a person to age in place is particularly needed in rural areas, where isolation may become dangerous. A better setting is a neighborhood or an apartment complex that has become a naturally occurring retirement community (NORC).

A NORC develops when young adults move into a new suburb or large building and then stay for decades as they age. People in NORCs may live alone, after children have left and partners have died. They enjoy home repair, housework, and gardening, partly because their lifelong neighbors notice the new curtains, the polished door, the blooming rose bush.

If low-

In many other ways, public and private institutions as well as neighbors support aging in place (A. Smith, 2009). That is true for Doris, my friend noted in the introduction to this chapter. Dozens of people in the community care for her. Recently in the park, two strangers started to talk with her. Half a dozen homeless men stopped what they were doing to watch, as the strangers’ body positions raised their suspicions. Nothing untoward happened, but one of the men approached and said, “OK Doris, I will walk you home.” Doris appreciated his protection; I do, too.

Public policy where Doris lives, as in other cities, affects all the elderly. Rents are reduced for seniors; special transportation is provided for those who cannot walk to the subway; aides, therapists, and meal services come to homes. Doris has made me well aware that all of these are flawed and inadequate. Nonetheless, she—

Religious Involvement

Older adults attend fewer religious services than do the middle-

Religious prohibitions encourage good habits (e.g., less drug use).

Faith communities promote caring relationships.

Beliefs give meaning for life and death, thus reducing stress.

[Atchley, 2009; Lim & Putnam, 2010; Noronha, 2015]

Religious identity and institutions are especially important for older members of minority groups, who often identify more strongly with their religious heritage than with their national or ethnic background. A nearby house of worship, with familiar words, music, and rituals, is one reason American elders prefer to age in place.

Immigrants bring their religion with them. About a third of all U.S. Catholics are immigrants, as are almost all U.S. Hindus and Buddhists and most U.S. Muslims (Pew Research Center, May 12, 2015). Although the average congregant in these newer groups is younger than the average devotee of the traditional U.S. Christian or Jewish groups, in every group the elderly members are usually the most devout. Religious faith seems to increase with age.

Faith may explain an oddity in mortality statistics, specifically in suicide data (Chatters et al., 2011). In the United States, suicide after age 65 among elderly European American men occurs 50 times more often than among African American women. One explanation is that African American women’s religious faith is often very strong, making them less depressed about their daily lives (Colbert et al., 2009).

Political Activity

It is easy to assume that elders are not political activists. Few turn out for rallies, and only about 2 percent are active in political campaigns. Indeed, in 2014, only 7 percent of U.S. residents older than 65 volunteered for any political, civic, international, or professional group (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 25, 2014).

By other measures, however, the elderly are very political. More than any other age group, they write letters to their representatives, identify with a political party, and vote.

In addition, they keep up with the news. The Pew Research Center for the People and the Press periodically asks a cross section of U.S. residents a dozen questions about current events. The elderly usually best the young. For example, elders (65 and older) beat the youngest (aged 18 to 30) by a ratio of about 3-

Many government policies affect the elderly, especially those regarding housing, pensions, prescription drugs, and medical costs. However, members of this age group do not necessarily vote their own economic interests or vote as a bloc. Instead, they are divided on most national issues, including global warming, military conflicts, and public education.

Political scientists believe the idea of “gray power” (that the elderly vote as a bloc) is a myth, promulgated to reduce support for programs that benefit the old (Walker, 2012). Given that ageism zigzags from hostile to benign—

In the United States, the media sometimes stereotypes people who support the Tea Party (about 18 percent of all adults in 2010) as elderly, but that is not accurate. Most Tea Party supporters are middle-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 15.12

1. Why would a person keep working after age 65?

A person may continue working based on financial need, because they like the status of the position, or because the job and community associated with work is something the person enjoys and values and is reluctant to give up.

Question 15.13

2. How does retirement affect the health of people who have worked all their lives?

If retirees voluntarily leave their jobs and engage in activities and intellectual challenges, they become healthier and happier than they were before.

Question 15.14

3. Who is more likely to volunteer and why?

According to official statistics, older adults volunteer less often than do middle-

Question 15.15

4. What are the benefits and liabilities for elders who want to age in place?

Many elders prefer to age in place, comfortable in the familiarity of their home and community. Such social ties lead to a greater sense of well-

Question 15.16

5. How does religion affect the well-

Religious practice correlates with health because religions tend to encourage healthy behaviors, provide opportunities for social engagement, offer insight on the meaning of life, and give hope in death. Religious institutions often provide a host of social services that benefit the elderly, while also providing a sense of community.

Question 15.17

6. How does the political activity of older and younger adults differ?

While older adults are less likely to be involved in campaigns and political activism, they are more likely to write to elected officials, to vote, and to follow current events.