Choices in Dying

Do you recoil at the heading, “Choices in Dying”? If so, you may be living in the wrong century. Every twenty-

It might seem that war deaths, or bystander gun deaths, or accidents of many kinds are not chosen. But always, decisions by the society, the family, or the individual make life or death more likely. For instance, 15,000 fewer motor-

A Good Death

People everywhere hope for a good death (Vogel, 2011), one that is:

At the end of a long life

Peaceful

Quick

In familiar surroundings

With family and friends present

Without pain, confusion, or discomfort

Many would add that control over circumstances and acceptance of the outcome are also characteristics of a good death, but on this cultures and individuals differ. Some dying individuals willingly cede control to doctors or caregivers, and others fight every sign that death is near. Some cultures praise the dying for non-

MODERN MEDICINE In some ways, modern medicine makes a good death more likely. The first item on the list has become the norm: Death usually occurs at the end of a long life.

Younger people still get sick, of course, but surgery, drugs, radiation, and rehabilitation typically mean that, in developed countries, the ill go to the hospital and then return home. If young people die, death is typically quick (before medical intervention could save them) and that makes it a good death for them (if not for their loved ones).

In other ways, however, contemporary medical advances have made a bad death more likely, especially the last items on this list. When a cure is impossible, physical and emotional comfort deteriorate (Kastenbaum, 2012). Instead of acceptance, people submit to surgery and drugs that prolong pain and confusion. Hospitals sometimes exclude visitors from intensive-

Video: The End of Life: Interview with Laura Rothenberg

The underlying problem may be medical care itself, which is so focused on lifesaving that dying invites “the dangers of well-

HONEST CONVERSATION In about 1960, researcher Elisabeth Kübler-

From ongoing interviews, Kübler-

Denial (“I am not really dying.”)

Anger (“I blame my doctors, or my family, or God for my death.”)

Bargaining (“I will be good from now on if I can live.”)

Depression (“I don’t care about anything; nothing matters anymore.”)

Acceptance (“I accept my death as part of life.”)

Another set of stages of dying is based on Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, first introduced in Chapter 1 (Zalenski & Raspa, 2006).

Physiological needs (freedom from pain)

Safety (no abandonment)

Love and acceptance (from close family and friends)

Respect (from caregivers)

Self-

actualization (appreciating one’s unique past and present)

Maslow later suggested a possible sixth stage, self-

Other researchers have not found these sequential stages. Remember the woman dying of a sarcoma, cited earlier? She said that she would never accept death and that Kübler-

Nevertheless, both lists remind caregivers that each dying person has strong emotions and needs that may be unlike that same person’s emotions and needs a few days or weeks earlier. Furthermore, those emotions may differ from those of the caregivers, who themselves may have different emotions from each other.

It is vital that everyone—

Most dying people want to be with loved ones and to talk honestly with medical and religious professionals. Individual differences continue, of course. Some people do not want the whole truth; some want every possible medical intervention to occur; some do not want many visitors. In many Asian families, telling people they are dying is thought to destroy hope (Corr & Corr, 2013a).

Better Ways to Die

Several practices have become more prevalent since the contrast between a good death and the traditional hospital death has become clear. The hospice and the palliative care specialty are examples.

hospice

An institution or program in which terminally ill patients receive palliative care to reduce suffering; family and friends of the dying are helped as well.

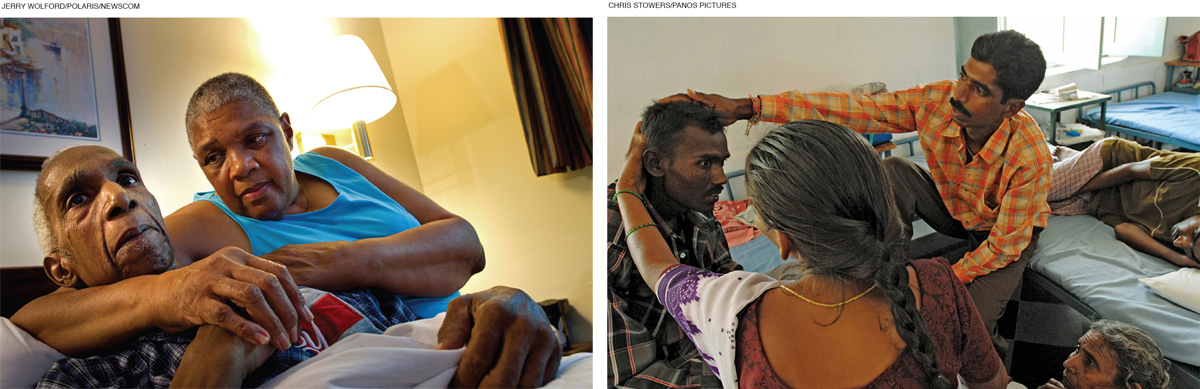

HOSPICE In 1950s London, Cecily Saunders opened the first modern hospice, where terminally ill people could spend their last days in comfort (Saunders, 1978). Thousands of other hospices have opened in many nations, and hundreds of thousands of hospice caregivers now bring medication and care to dying people where they live. In the United States, more than half of all hospice deaths occur at home (NHPCO, 2014).

Hospice professionals relieve discomfort, avoiding measures that merely delay death; their aim is to make dying easier. Comfort can include measures that some hospitals forbid: acupuncture, special foods, flexible schedules, visitors when the patient wants them (which could be 2 A.M.), massage, aromatic oils, and so on (Doka, 2013).

There are two principles for hospice care:

Each patient’s autonomy and decisions are respected. For example, pain medication is readily available, not on a schedule or minimal dosage. Most hospice patients use less medication than a doctor might prescribe, but they decide when to take it and how much they want.

Family members and friends are counseled before the death, taught to provide care, and guided in mourning. Their needs are as important as those of the patient. Death is thought to happen to a family, not just to an individual.

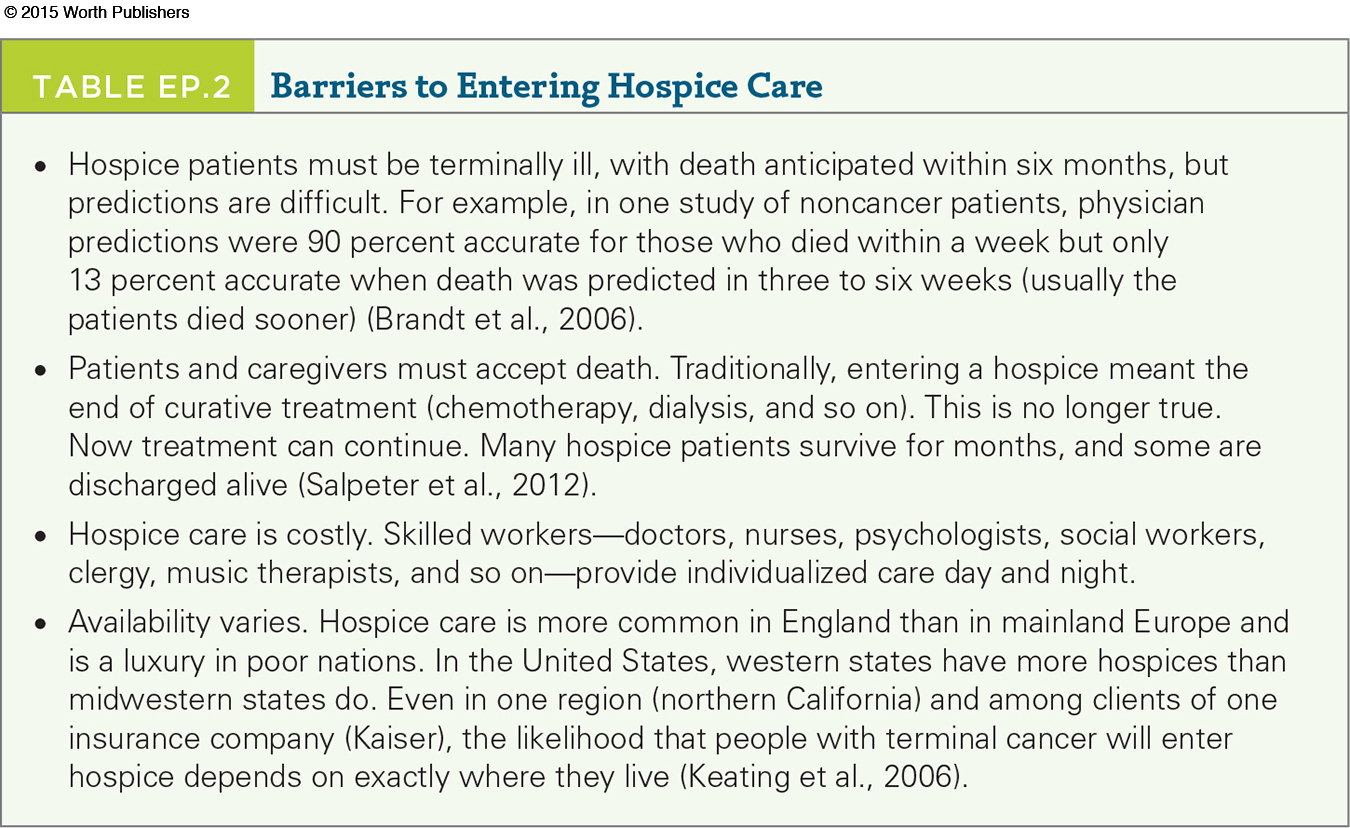

In 2013 in the United States, 43 percent of deaths occurred with hospice care, one-

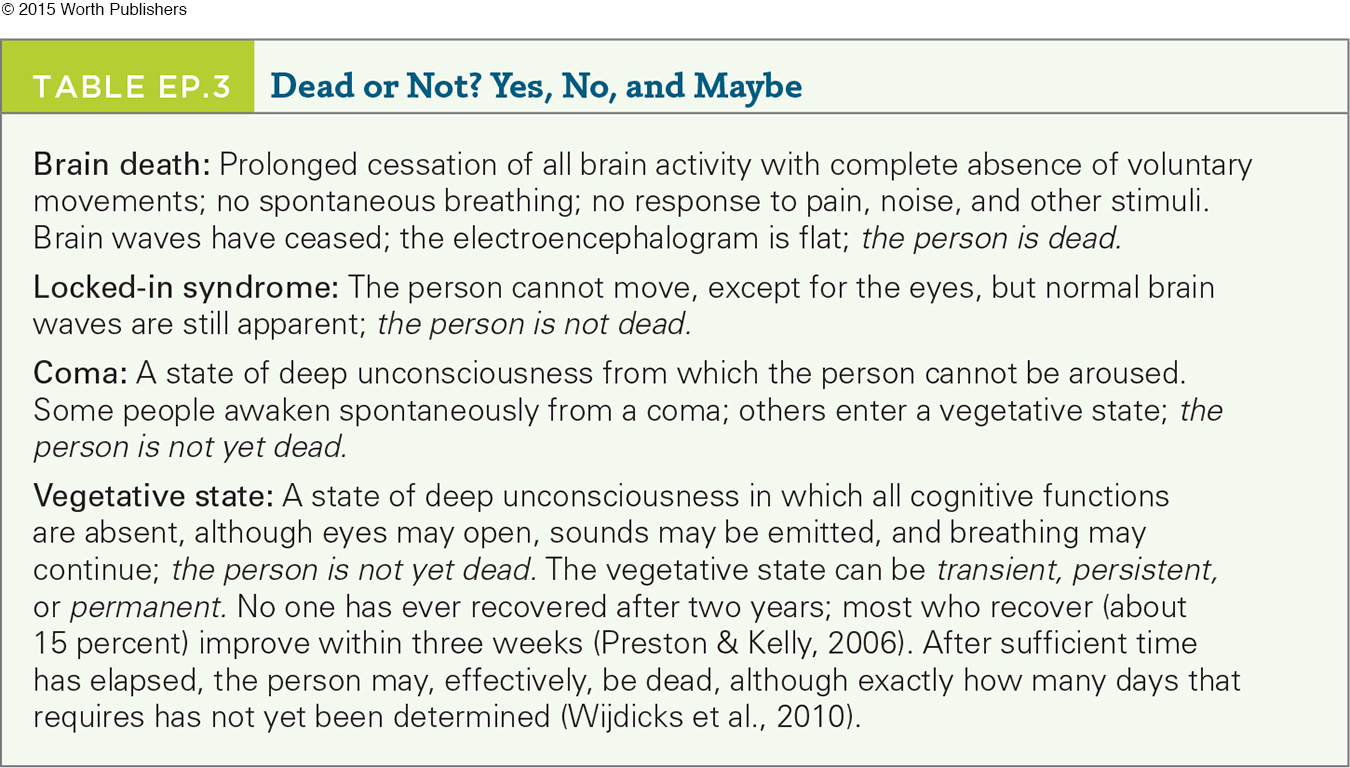

Unfortunately, hospice does not reach many dying people (see Table EP.2), even in wealthy nations, much less in developing ones (Kiernan, 2010).

THINK CRITICALLY: What are the possible reasons that fewer people in hospice are from non-

There are ethnic differences as well. In the United States, only 6 percent of hospice patients are Latino (NHPCO, 2014). Compared to European Americans, African Americans are more often admitted to hospice from a hospital than from a home and are likely to die relatively quickly (one week, on average), whereas the average hospice death occurs two weeks after admission (K. S. Johnson et al., 2011). The reason is thought to be cultural, not economic, since Medicare now pays most hospice expenses.

Nationally, about 15 percent of hospice patients are discharged alive. Sometimes their health has improved. However, the hospices with the highest “live discharge” rates tend to be recently founded, private, profit-

Home hospice care requires family or friends trained by hospice workers to provide care. Although this has led to an increase of “good deaths” at home, not everyone has available caregivers. Most deaths still occur in hospitals, and many others occur in nursing homes (see Figure EP.4).

palliative care

Medical treatment designed primarily to provide physical and emotional comfort to the dying patient and guidance to his or her loved ones.

PALLIATIVE CARE In 2006, the American Medical Association approved a new specialty, palliative care, which focuses on relieving pain and suffering, in hospitals, homes, or hospice. Palliative doctors are trained to discuss options with patients and their families. Some interventions (especially surgery) may be refused if people understand the risks and benefits (Mynatt & Mowery, 2013). Palliative doctors also prescribe powerful drugs and procedures that make patients comfortable.

double effect

When an action (such as administering opiates) has two effects, such as relieving pain and suppressing respiration.

Morphine and other opiates have a double effect: They relieve pain (a positive effect), but they also slow down respiration (a negative effect). Painkillers that reduce both pain and breathing are allowed by law, ethics, and medical practice.

In England, for instance, although it is illegal to cause death, even of a terminally ill patient who repeatedly asks to die, it is legal to prescribe drugs that have a double effect. One-

Heavy sedation is another method sometimes used to alleviate pain. Concerns have been raised that this may merely delay death rather than prolong meaningful life, since the patient becomes unconscious, unable to think or feel (Raus et al., 2011).

Ethical Issues

As you see, the success of medicine has created new dilemmas. Death is no longer the natural outcome of age and disease; when and how death occurs involves human choices.

DECIDING WHEN DEATH OCCURS No longer does death necessarily occur when a vital organ stops. Breathing continues with respirators; stopped hearts are restarted; stomach tubes provide calories; drugs fight pneumonia.

Almost every life-

THINK CRITICALLY: At what point, if ever, should intervention stop in order to allow death?

Religious advisers, doctors, and lawyers disagree with colleagues within their respective professions. Family members disagree with one another. Members of every group disagree with members of their own group and the other groups (Ball, 2012; Engelhardt, 2012; Nelson-

One physician, a specialist in palliative care, advised his colleagues:

The highway of aggressive medical treatment runs fast, is heavily travelled, but can lack landmarks and the signage necessary to know when it is time to make for the exit ramp . . . These signs are there and it is your responsibility to communicate them to patients and families.

[Fins, 2006, p. 73]

Good advice, hard to follow.

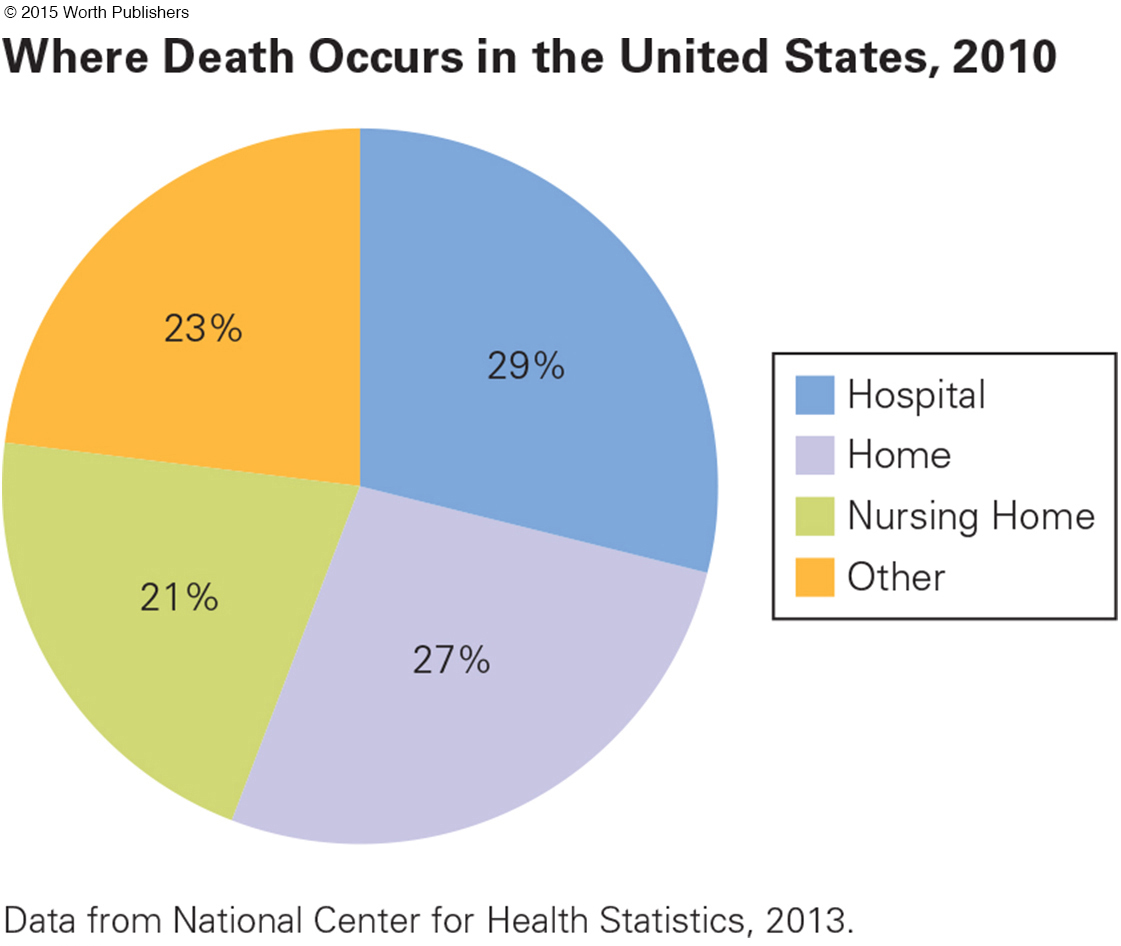

EVIDENCE OF DEATH Historically, death was determined by listening to a person’s chest: No heartbeat meant death. To make sure, a feather was put to the person’s nose to indicate respiration—

Modern medicine has changed that: Hearts and lungs need not function on their own. Many life-

But how do we know when death has happened? In the late 1970s, a group of Harvard physicians concluded that death occurred when brain waves ceased, a definition now used worldwide (Wijdicks et al., 2010). However, many doctors believe that death can occur even if primitive brain waves continue (Kellehear, 2008; Truog, 2007) (see Table EP.3).

It is critical to know when people are in a permanent vegetative state (and thus will never regain the ability to think) and when they are merely in a coma but might recover. One crucial factor is whether the person could ever again breathe without a respirator, but that is hard to guarantee if “ever again” includes 10 or 20 years hence.

In 2008, the American Academy of Neurology gathered experts to conduct a meta-

As this article points out, everyone needs to know when a person is brain-

Consequently, a person who wanted to donate organs after death is unable to do so because so much time elapsed between death and donation that the organs are no longer usable. A survey of many nations found that there is no international agreement as to brain death, nor does that seem possible in the near future (Wahlster et al., 2015).

passive euthanasia

When a person is allowed to die naturally, instead of intervening with active attempts to prolong life.

DNR (do not resuscitate) order

A written order from a physician (sometimes initiated by a patient’s advance directive or by a health care proxy’s request) that no attempt should be made to revive a patient if he or she suffers cardiac or respiratory arrest.

EUTHANASIA Euthanasia, sometimes called mercy killing, is common for pets but rare for people. Many people see a major distinction between active and passive euthanasia, although the final result is the same. In passive euthanasia, a person near death is allowed to die. They may have a DNR (do not resuscitate) order, instructing medical staff not to restore breathing or restart the heart if breathing or pulsating stops.

Passive euthanasia is legal everywhere if the dying person chooses it, but many emergency personnel start artificial respiration and stimulate hearts without asking whether a patient has a DNR. That makes passive euthanasia impossible.

active euthanasia

When someone does something that hastens another person’s death, hoping to end that person’s suffering.

Active euthanasia is deliberately doing something to cause death, such as turning off a respirator or giving a lethal drug. Some physicians condone active euthanasia when three conditions occur: (1) suffering cannot be relieved, (2) incurable illness, and (3) a patient who wants to die. Active euthanasia is legal in the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Switzerland, and illegal (but rarely prosecuted) elsewhere.

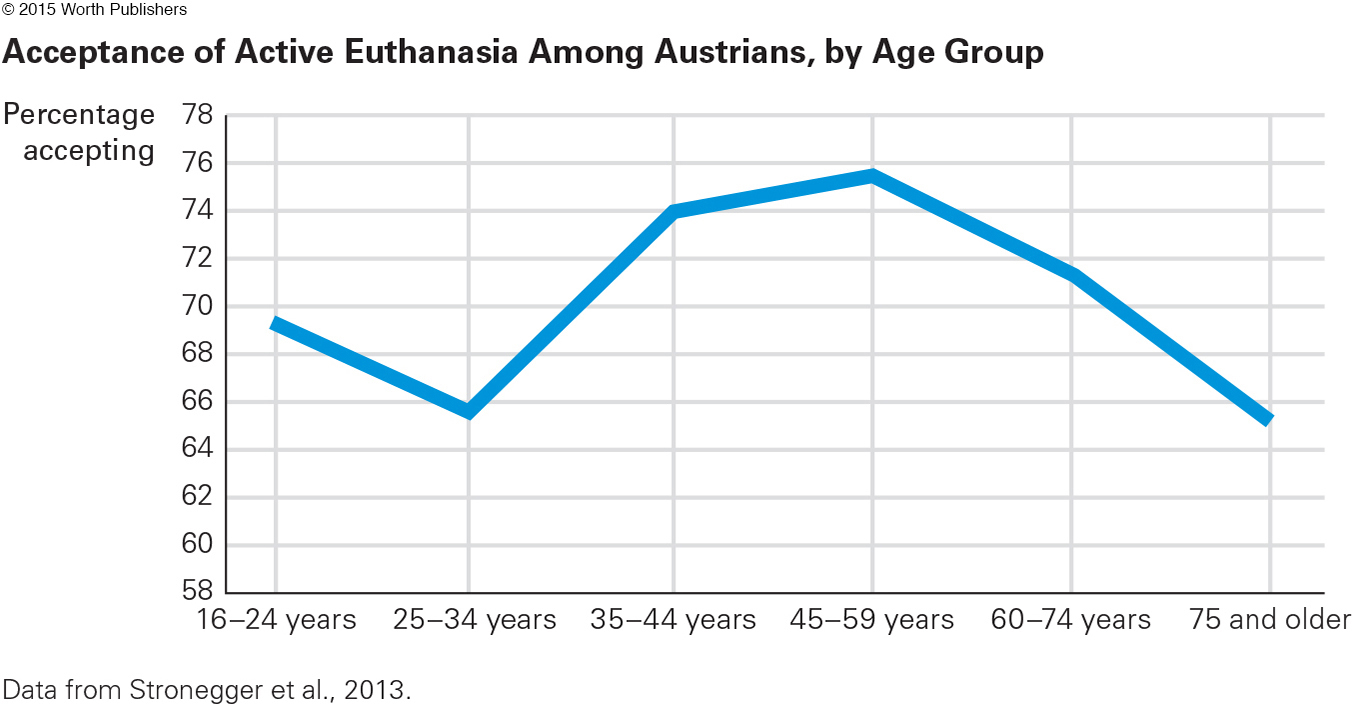

Attitudes may be changing. For example, over the past decade in Austria, doctors in training have increasingly valued patients’ autonomy, which has led to more acceptance of active euthanasia (Stronegger et al., 2013) (see Figure EP.5). In every nation surveyed, some physicians would never perform active euthanasia and others have done so. Opinions from the public vary as well, although generally nations in eastern Europe are less accepting than those in western Europe (J. Cohen et al., 2013).

physician-

A form of active euthanasia in which a doctor provides the means for someone to end his or her own life, usually by prescribing lethal drugs.

THE DOCTOR’S ROLE Between passive and active euthanasia is another option: A doctor may provide the means for patients to end their own lives, typically by prescribing lethal medication. This is called physician-

Physician-

Question 16.12

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Where did this rally take place?

Paris, France. Two clues: That is the Eiffel Tower, and François Hollande was elected president of France in 2012.

For example, some cultures believe that suicide may be noble, as when Buddhist monks publicly burned themselves to death to advocate Tibetan independence from China, or when people choose to die for the honor of their nation or themselves. However, in the United States, physicians of Asian heritage are less likely to condone physician-

This reluctance of Asian doctors to speed up death helps explain a practice in Thailand: When it becomes apparent that a hospitalized patient will soon die, an ambulance takes that person back home, where death occurs naturally. Then the person and the family can benefit from a better understanding of life, suffering, and death (Stonington, 2012).

PAIN: PHYSICAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL The Netherlands has permitted active euthanasia and physician-

However, a qualitative analysis found that “fatigue, pain, decline, negative feelings, loss of self, fear of future suffering, dependency, loss of autonomy, being worn out, being a burden, loneliness, loss of all that makes life worth living, hopelessness, pointlessness and being tired of living were constituent elements of unbearable suffering” (Dees et al., 2011, p. 727). Obviously, medication cannot alleviate all that.

Oregon voters approved physician-

The dying person must be an Oregon resident and over age 17.

The dying person must request the lethal drugs twice orally and once in writing.

Fifteen days must elapse between the first request and the prescription.

Two physicians must confirm that the person is terminally ill, has less than six months to live, and is competent (i.e., not mentally impaired or depressed).

The law also requires record-

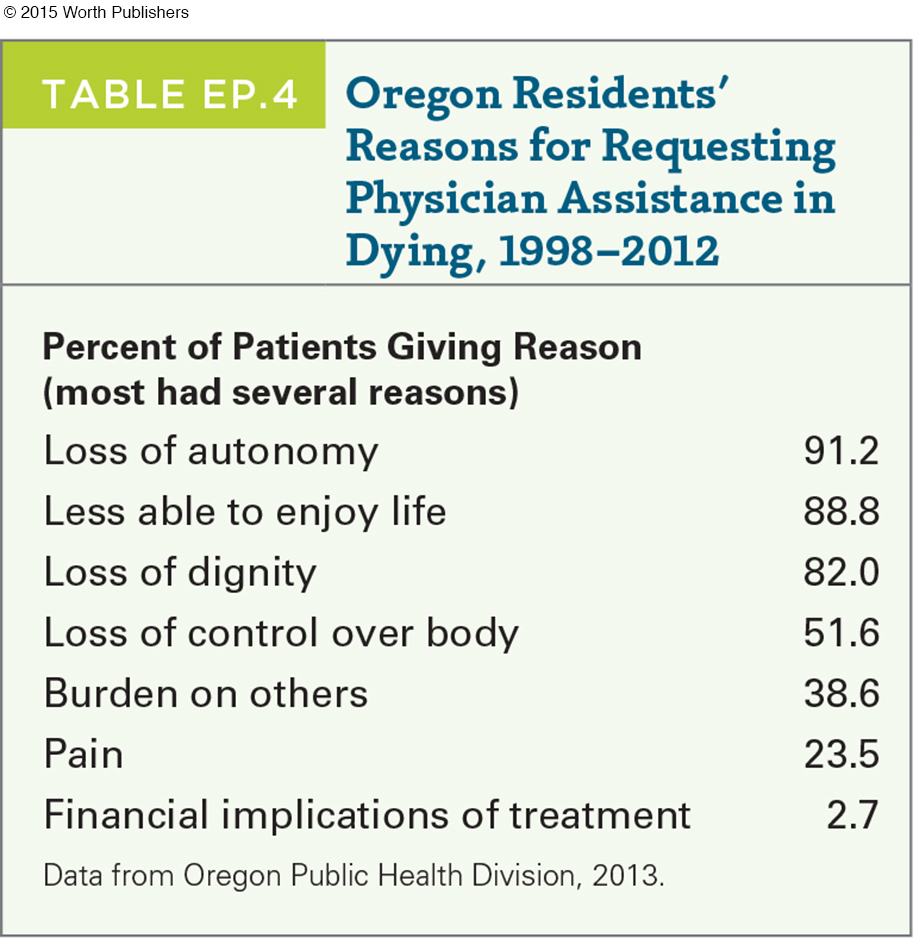

As Table EP.4 shows, Oregon residents requested the drugs primarily for psychological, not biological, reasons—

THINK CRITICALLY: Why would someone take all the steps to obtain a lethal prescription and then not use it?

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

The “Right to Die”?

slippery slope

The argument that a given action will start a chain of events that will culminate in an undesirable outcome.

Many people fear that legalizing euthanasia or physician-

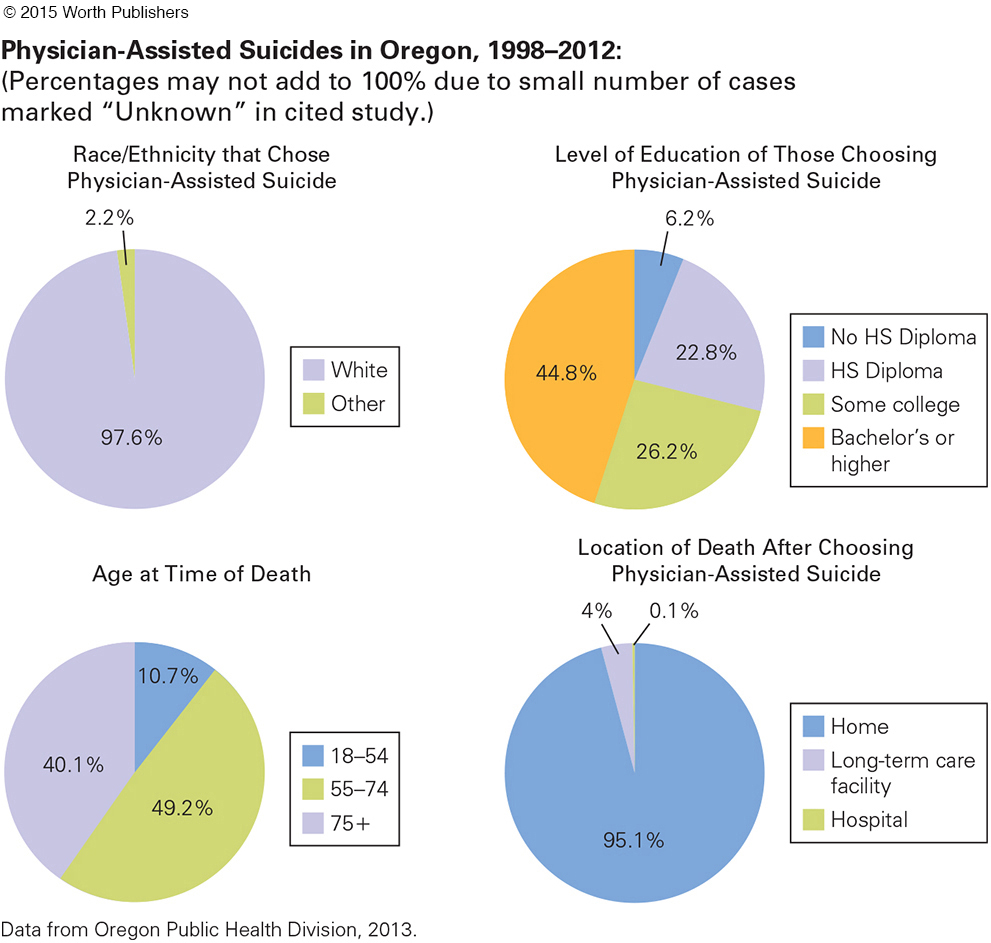

In Oregon and the Netherlands, people from non-

All these statistics refute both the slippery-

The 1980 Netherlands law was revised in 2002 to allow euthanasia not only when a person is terminally ill but also when a person is chronically ill and in pain. The number of Dutch people who choose euthanasia is increasing, about 1 in 30 deaths in 2012. Is this a slippery slope? Some people think so, especially those who believe that God alone decides the moment of death and that anyone who interferes is defying God.

Arguing against that perspective, a cancer specialist writes:

To be forced to continue living a life that one deems intolerable when there are doctors who are willing either to end one’s life or to assist one in ending one’s own life, is an unspeakable violation of an individual’s freedom to live—

[Benatar, 2011, p. 206]

Not everyone agrees with that cancer specialist. Might the decision to die be evidence of depression? If so, no physician should prescribe lethal drugs (Finlay & George, 2011). Declining ability to enjoy life was cited by 89 percent of Oregonians who requested physician-

Acceptance of death signifies mental health in the aged but not necessarily in the young: Should death with dignity be allowed only after age 54? That would have excluded 11 percent of Oregonians who have used the act thus far. Is the idea that only the old be allowed to choose death an ageist idea, perhaps assuming that the young don’t understand what they are choosing or that the old are the ones for whom life is over?

The number of people who die by taking advantage of Oregon’s law has increased steadily, from 16 in 1998 (the first year) to 77 in 2012. Some might see that as evidence of a slippery slope. Others consider it proof that the practice is useful though rare—

People with disabling, painful, and terminal conditions who die after choosing futile measures to prolong life are eulogized as “fighters” who “never gave up.” That indicates social approval of such choices. This same attitude about life and death is held by most voters and lawmakers around the world. The majority oppose laws that allow physician-

However, that majority is not evident everywhere.

In November 2008, in the state of Washington, just north of Oregon, 58 percent of voters approved a death with dignity law.

In 2009, Luxembourg joined the Netherlands and Belgium in allowing active euthanasia.

In 2011, the Montana senate refused to forbid physician-

assisted suicide. In 2012, a legal scholar contended that the U.S. Constitution’s defense of liberty includes the freedom to decide how to die (Ball, 2012).

In 2013, Vermont joined Oregon.

In 2014, New Mexico courts allowed such deaths (but legislators may disallow it in 2015).

In October 2015, after California’s End of Life Option Act passed in the state Senate and Assembly, Governor Jerry Brown signed the bill into law.

All that might seem like a growing trend, but proposals to legalize physician-

advance directives

Any description of what a person wants to happen as they die and after they die. This can include medical measures, visitors, funeral arrangements, cremation and so on.

ADVANCE DIRECTIVES Advance directives can describe everything regarding end-

Among the explicit statements in medical directives are: whether artificial feeding, breathing, or heart stimulation should be used; whether antibiotics that might merely prolong life or pain medication that causes coma or hallucinations are desired; whether religious music or clergy are welcome; and so on.

The legality of such directives varies by jurisdiction. Sometimes a lawyer is needed to ensure that documents are legal; sometimes a written request, signed and witnessed, is adequate.

Many people want personal choice about death; thus they approve of advance directives in theory but are uncertain about specifics. For example, few know that restarting the heart may extend life for decades in a healthy young adult but is likely to cause major brain damage, or merely prolong dying, in an elderly person whose health is failing.

Added to the complications are personal factors, such as additional morbidities and exactly what other factors are present. For example, the effect of cardiopulmonary resuscitation depends partly on how long the heart has stopped (Bass, 2011). Data on overall averages are contradictory (Elliot et al., 2011). Furthermore, the data given to family about the consequences may include only the medical consequences for survivors, not the odds of death.

Even talking about choices is controversial. Originally, the U.S. health care bill passed in 2010 allowed doctors to be paid for describing treatment options (e.g., Kettl, 2010). Opponents called those “death panels,” an accusation that almost torpedoed the entire package. As a result, that measure was scrapped: Physicians cannot bill for time spent explaining palliative care, options for treatment, or dying.

WILLS AND PROXIES Advance directives often include a living will and/or a health care proxy. Hospitals and hospices strongly recommend both of these. Nonetheless, most people resist: A study of cancer patients in a leading hospital found that only 16 percent had living wills and only 48 percent had designated a proxy (Halpern et al., 2011).

living will

A document that indicates what medical intervention an individual prefers if he or she is not conscious when a decision is to be expressed. For example, some do not want mechanical breathing.

A living will indicates what sort of medical intervention a person wants or does not want in the event that they become unable to express their preferences. (If the person is conscious, hospital personnel ask about each specific procedure, often requiring written consent before surgery. Patients who are conscious and lucid can choose to override any instructions they wrote earlier in their living will.)

The reason a person might want to override their own earlier wishes is that living wills include phrases such as “incurable,” “reasonable chance of recovery,” and “extraordinary measures,” and it is difficult to know what those phrases mean until a specific issue arises. Even then, medical judgments vary. Doctors and family members disagree about what is “extraordinary” or “reasonable.”

health care proxy

A person chosen to make medical decisions if a patient is unable to do so, as when in a coma.

Some people designate a health care proxy—another person to make medical decisions for them if they become unable to do so. That seems logical, but unfortunately neither a living will nor a health care proxy guarantees that medical care will be exactly what a person would choose.

For one thing, proxies find it difficult to allow a loved one to die. A larger problem is that few people—

Medical professionals advocate advance directives, but they also acknowledge the problems with them. As one couple wrote:

Working within the reality of mortality, coming to death is then an inevitable part of life, an event to be lived rather than a problem to be solved. Ideally, we would live the end of our life from the same values that have given meaning to the story of our life up to that time. But in a medical crisis, there is little time, language, or ritual to guide patients and their families in conceptualizing or expressing their values and goals.

[Farber & Farber, 2014, p. 109]

THE SCHIAVO CASE A famous example of the need for a health care proxy occurred with Theresa (Terri) Schiavo, who was 26 years old when her heart suddenly stopped. Emergency personnel restarted her heart, but she fell into a deep coma. Like almost everyone her age, Terri had no advance directives. A court designated Michael, her husband of six years, as her proxy.

Michael attempted many measures to bring back his wife, but after 11 years he accepted her doctors’ repeated diagnosis: Terri was in a persistent vegetative state. He petitioned to have her feeding tube removed. The court agreed, noting the testimony of witnesses who said that Terri had told them that she never wanted to be on life support. Terri’s parents appealed the decision but lost. They pleaded with the public.

The Florida legislature responded, passing a law that required that the tube be reinserted. After three more years of legal wrangling, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the lower courts were correct and the legislature overstepped its authority. At this point, every North American newspaper and TV station was following the case. Congress passed a law requiring that artificial feeding be continued, but that law, too, was overturned as unconstitutional.

The stomach tube was removed, and Terri died on March 31, 2005—

Partly because of the conflicts among family members and between appointed judges and elected politicians, Terri’s case caught media attention, inspiring vigils and protests. Lost in that blitz are the thousands of other mothers and fathers, husbands and wives, sons and daughters, judges and legislators, doctors and nurses who struggle less publicly with similar issues. As of 2015, the underlying problems have not been solved.

Advance directives may provide caregivers some peace. But, as the Schiavo case makes clear, discussion with every family member is needed long before a crisis occurs (Rogne & McCune, 2014).

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 16.13

1. What is a good death?

A good death is typically thought to take place after a long life, peacefully, quickly, in a familiar place, surrounded by loved ones, and without pain or discomfort.

Question 16.14

2. According to Kübler-

Kübler-

Question 16.15

3. Why doesn’t everyone agree with Kübler-

Some people do not agree with her stages because not everyone moves through all five stages in this order—

Question 16.16

4. What determines whether a dying person will receive hospice care?

Hospice patients must be terminally ill, with death anticipated within six months, and the patient and his or her family must be willing to accept death. In addition, where a person lives and even insurance (or ability to pay) are factors in determining if a person will receive hospice care.

Question 16.17

5. What are the guiding principles of hospice care, and why is each important?

Two guiding principles for hospice care are that the dying person’s autonomy and decisions be respected, and that the needs of the mourners be met. By providing the kind of environment and pain management a patient desires, and by supporting mourners during and after the loss of a loved one, hospice aims to make the dying process easier and less frightening.

Question 16.18

6. Why is the double effect legal everywhere, even though it speeds death?

Morphine and other opiates have a double effect: They relieve pain (a positive effect), but they also slow down respiration (a negative effect). A painkiller that reduces pain but also breathing is allowed by law, ethics, and medical practice.

Question 16.19

7. What differences of opinion are there with respect to the definition of death?

While the prevailing opinion for decades was that death occurred when brain waves stopped, many doctors now argue that a person may still have primitive brain waves even after death. Researchers seek to more clearly distinguish between people in a permanent vegetative state and those in a coma, from which they may recover.

Question 16.20

8. What is the difference between passive and active euthanasia?

In passive euthanasia, a person is allowed to die naturally, through the cessation of medical intervention. In active euthanasia, someone takes action to bring about another person’s death, with the intention of ending that person’s suffering.

Question 16.21

9. What are the four conditions of physician-

1) The dying person must be an adult and an Oregon resident (which is important since physician-

Question 16.22

10. Why would a person who has a living will also need a health care proxy?

Living wills stipulate the medical interventions that people would like to have (or not have) if they are ever unconscious and unable to articulate these preferences for themselves. However, no document can completely cover every circumstance and situation. A health care proxy is a person designated to make medical decisions for another person; in the event that a situation that is not clearly identified in a living will emerges, the person’s health care proxy would be called upon to make decisions for the person.