The Life-Span Perspective

life-

An approach to the study of human development that takes into account all phases of life, not just childhood or adulthood.

The life-

|

Infancy Early childhood Middle childhood Adolescence Emerging adulthood Adulthood Late adulthood |

0 to 2 years 2 to 6 years 6 to 11 years 11 to 18 years 18 to 25 years 25 to 65 years 65 years and older |

As you will learn, developmentalists are reluctant to specify chronological ages for any period of development, since time is only one of many variables that affect each person. However, age is a crucial variable, and development can be segmented into periods of study. Approximate ages for each period are given here.

Development Is Multi-Directional

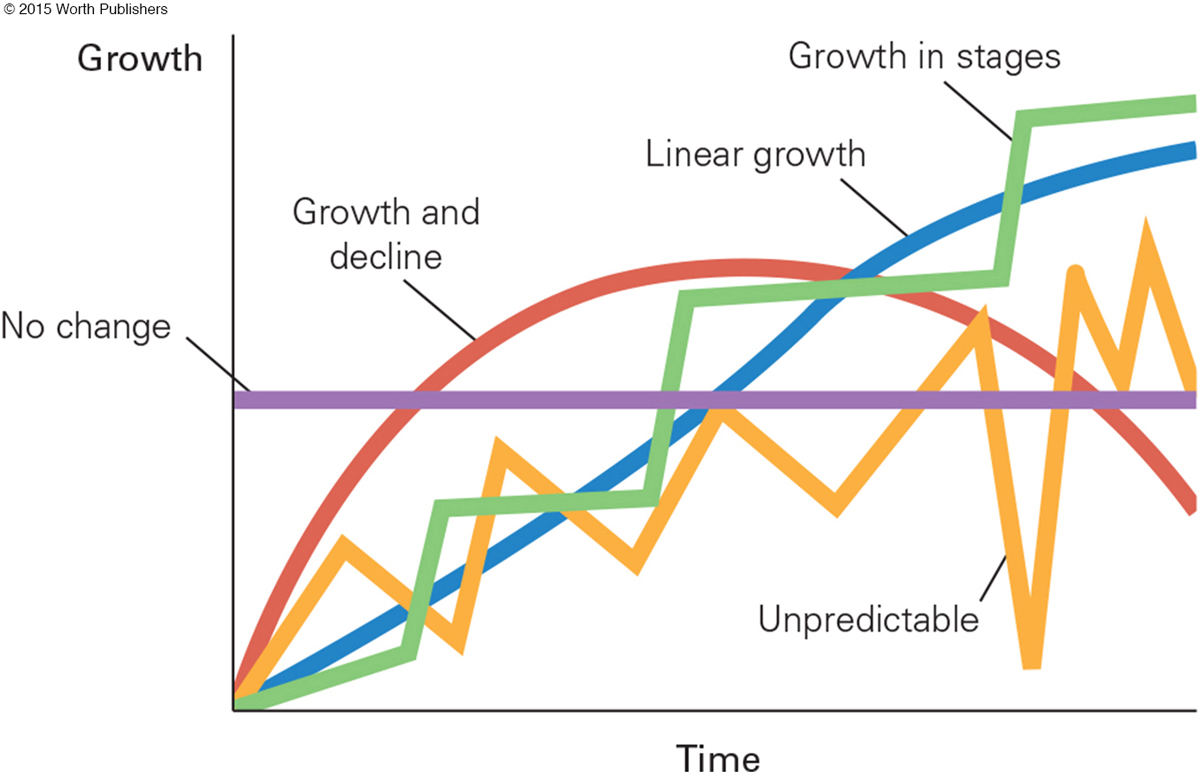

Multiple changes, in every direction, characterize the life span: Development is multi-

The pace of change varies as well. Sometimes discontinuity is evident: Change can occur rapidly and dramatically, as when caterpillars become butterflies. Sometimes continuity is found: Growth can be gradual, as when redwoods grow taller over hundreds of years.

Even stability is possible. Some characteristics seem not to change. For instance, chromosomal sex is lifelong: A zygote that is XY or XX (male or female) for life. Of course, the power and meaning of that biological fact change, but the chromosomes themselves stay the same.

There is simple growth, radical transformation, improvement, and decline as well as stability, stages, and continuity—

critical period

A time when a particular type of developmental growth (in body or behavior) must happen for normal development to occur.

CRITICAL PERIODS The speed and timing of impairments or improvements vary as well. Some changes are sudden and profound because of a critical period, a time when something must occur for normal development or the only time when an abnormality can occur. For instance, the critical period for humans to grow arms and legs, hands and feet, fingers and toes, is between 28 and 54 days after conception.

After day 54, that critical period is over. Unlike some insects, humans never grow replacement limbs or digits.

We know the critical period for limb formation because of a tragic occurrence. Between 1957 and 1961, thousands of newly pregnant women in 30 nations took thalidomide, an antinausea drug. This change in nurture (via the mother’s bloodstream) disrupted nature (the embryo’s genetic program).

If an expectant woman swallowed thalidomide between day 28 and 54, her newborn’s arms or legs were malformed or absent (Moore & Persaud, 2007). Whether all four limbs, or just arms, or just hands were missing depended on dose and timing. If thalidomide was ingested only after day 54, the newborn had normal body structures.

sensitive period

A time when a certain type of development is most likely, although it may still happen later with more difficulty. For example, early childhood is considered a sensitive period for language learning.

SENSITIVE PERIODS Life has few critical periods. Often, however, a particular development occurs more easily—

An example is found in language. If children do not communicate in their first language between ages 1 and 3, they might do so later (hence, these years are not critical), but their grammar is often impaired (hence, these years are sensitive).

Similarly, childhood is a sensitive period for learning to pronounce a second or third language. A new language can be learned in adulthood, but strangers might detect an accent and ask, “Where are you from?”

Often in development, individual exceptions to general patterns occur. Accent-

Because of sensitive periods, however, such exceptions are rare. A study of native Dutch speakers who become fluent in English found only 5 percent had mastered native English (Schmid et al., 2014).

Development Is Multi-Contextual

The second insight from the life-

A student might choose to go to a party instead of to the library. The social context of the party, such as whether drinks are free, the music lively, and friends are there, influences that student’s next several decisions. As you can imagine, the context of the party, and the decisions influenced by that context, affect later development: It may be hard to go to class the next day, or, in class, hard to apply math formulas or history facts. Each individual is responsible for his or her actions, of course, but social contexts are powerful.

ecological-

A perspective on human development that considers all the influences from the various contexts of development. (Later renamed bioecological theory.)

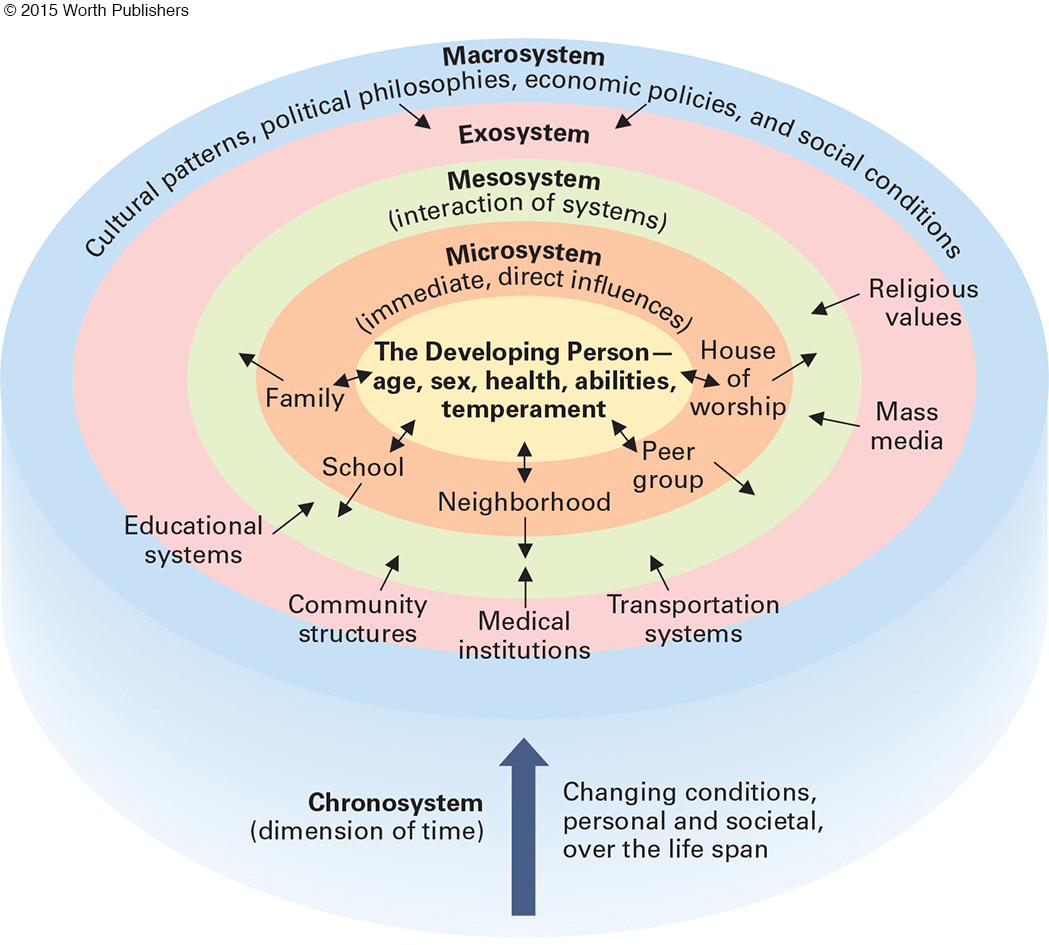

ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS A leading developmentalist, Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917–

The ecological-

Bronfenbrenner also stressed the role of historical conditions and therefore included the chronosystem (literally, “time system”). Further, because he appreciated the dynamic interaction among all the systems, he included a fifth system, the mesosystem, consisting of the connections between and among the other systems.

Throughout his life, Bronfenbrenner studied people in natural settings, interacting with each other at home, at school, or at work instead of coming to a scientist’s laboratory or answering questionnaires. Before he died, he renamed his approach bioecological to highlight the role of biology, recognizing that systems within the body (e.g., the sexual-

As you can see, a contextual approach to development requires simultaneous consideration of many systems. Two contexts—

cohort

People born within the same historical period who therefore move through life together, experiencing historical events (such as wars), new technologies (such as the smartphone), and cultural shifts (such as women’s liberation) at the same ages. For example, the effect of the Internet varies depending on what cohort a person belongs to.

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT All persons born within a few years of one another are said to be a cohort, a group defined by its members’ shared age. Cohorts travel through life together, affected by the interaction of their chronological age with the values, events, technologies, and culture of the era.

If you doubt that historical trends and events touch individuals, consider first names (see Table 1.2). If you know someone named Sophia, she is probably young—

|

Girls: 2013: Sophia, Emma, Olivia, Isabella, Ava 1993: Jessica, Ashley, Sarah, Samantha, Emily 1973: Jennifer, Amy, Michelle, Kimberly, Lisa 1953: Mary, Linda, Deborah, Patricia, Susan 1933: Mary, Betty, Barbara, Dorothy, Joan Boys: 2013: Noah, Liam, Jacob, Mason, William 1993: Michael, Christopher, Matthew, Joshua, Tyler 1973: Michael, Christopher, Jason, James, David 1953:Robert, James, Michael, John, David 1933:Robert, James, John, William, Richard |

Data from U.S. Social Security Administration

Two of my daughters, Rachel and Sarah, have names that were common when they were born: One wishes she had a more unusual name, the other is glad she does not. Your own name is influenced by history; your reaction is yours. Nurture and nature again.

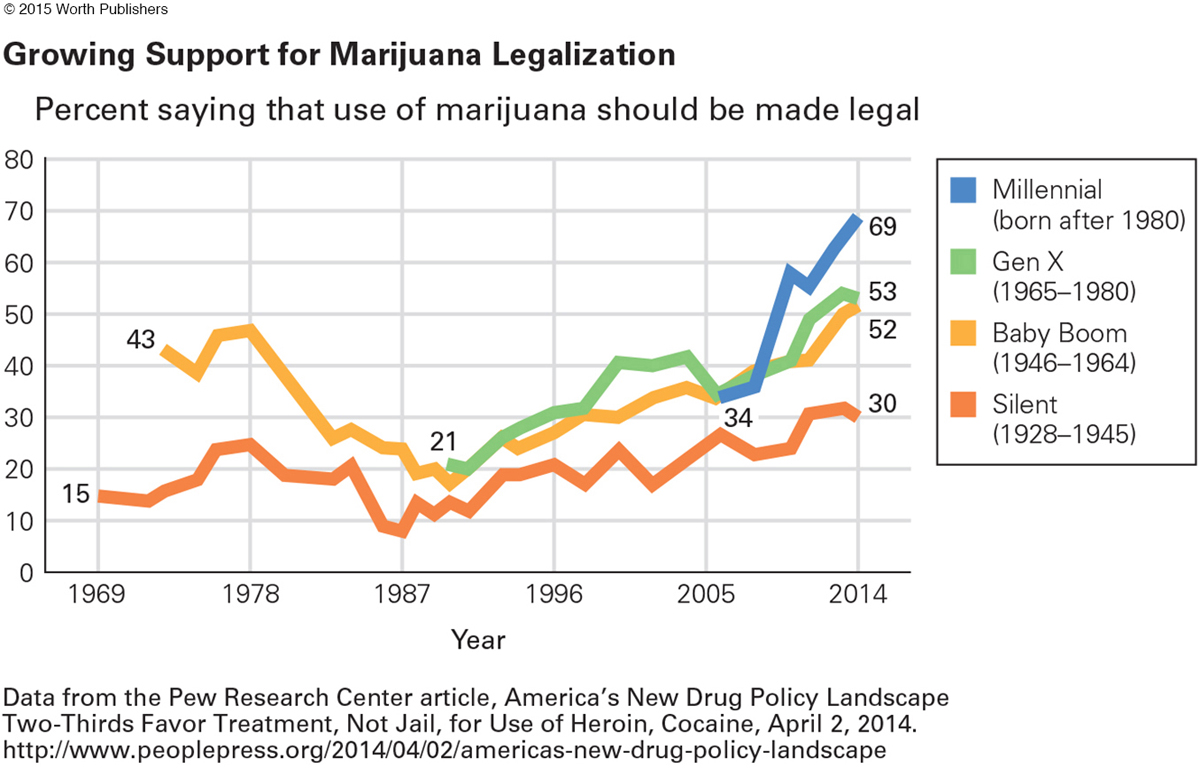

Cohort, more than generation, influences attitudes and behavior. Consider marijuana. In the United States in the 1930s, marijuana was declared illegal, but enforcement was erratic, and some cultures encouraged everyone to smoke “weed.” Virtually all the popular musicians of the 1960s—

Then, during the “war on drugs” in the 1980s, marijuana was labeled a gateway drug, likely to open the floodgates to serious abuse and addiction (Kandel, 2002). People were arrested and jailed for possession of even a few grams.

From 1990 on, attitudes gradually shifted again, such that by 2014 recreational marijuana use became legal in Uruguay and in four U.S. states, with medical use permitted in several others (see Figure 1.6). According to a Gallup poll, more than half (54 percent) of Americans approve legalization of marijuana (Motel, 2014).

Question 1.8

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Why is the line for Millennials much shorter than the line for the Silent Generation?

Because surveys rarely ask children their opinions, and the Millennials did not reach adulthood until about 2005.

Adolescents are particularly affected by historical shifts, including those regarding marijuana use. In 1978, only 12 percent of high school students thought experimental use of marijuana was harmful, and more than half had tried the drug. Thirteen years later, 80 percent thought there was “great risk” in regular use, and most were suspicious of experimental use.

Every year since then, marijuana use has increased and attitudes have become more accepting. In 2013, about one-

socioeconomic status (SES)

A person’s position in society as determined by income, occupation, education, and place of residence. (Sometimes called social class.)

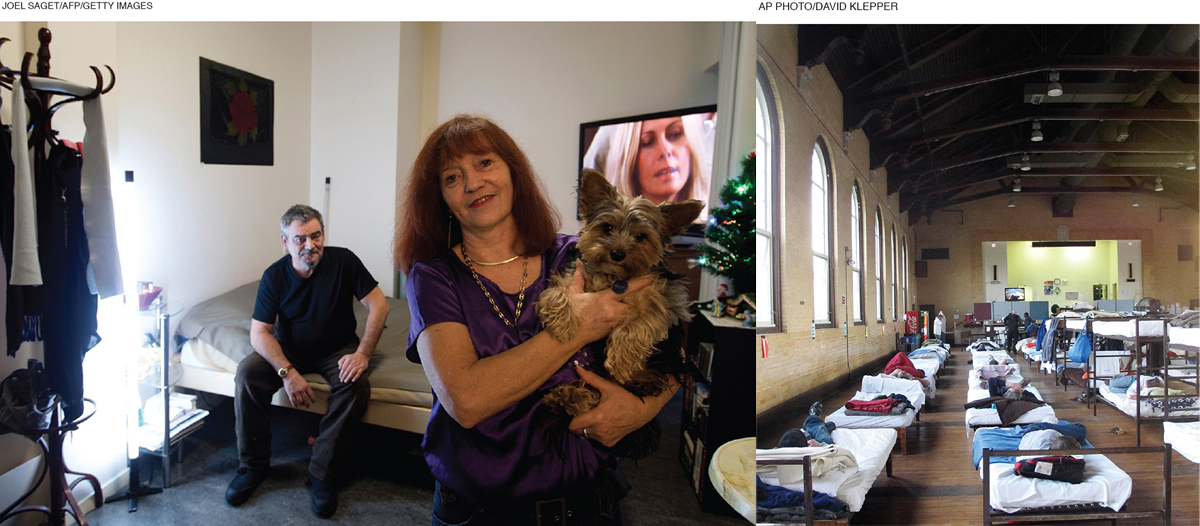

THE SOCIOECONOMIC CONTEXT Another influential context is economic, reflected in a person’s socioeconomic status, abbreviated SES. (Sometimes SES is called social class as in middle class or working class.) SES reflects income and much more, including occupation, education, and neighborhood.

Suppose a U.S. family is comprised of an infant, an unemployed mother, and a father who earns $18,000 a year. Their SES would be low if the wage earner is a high school dropout working 40 hours a week at minimum wage and living in a city slum, but it would be much higher if the wage earner is a postdoctoral student living on campus and teaching part time.

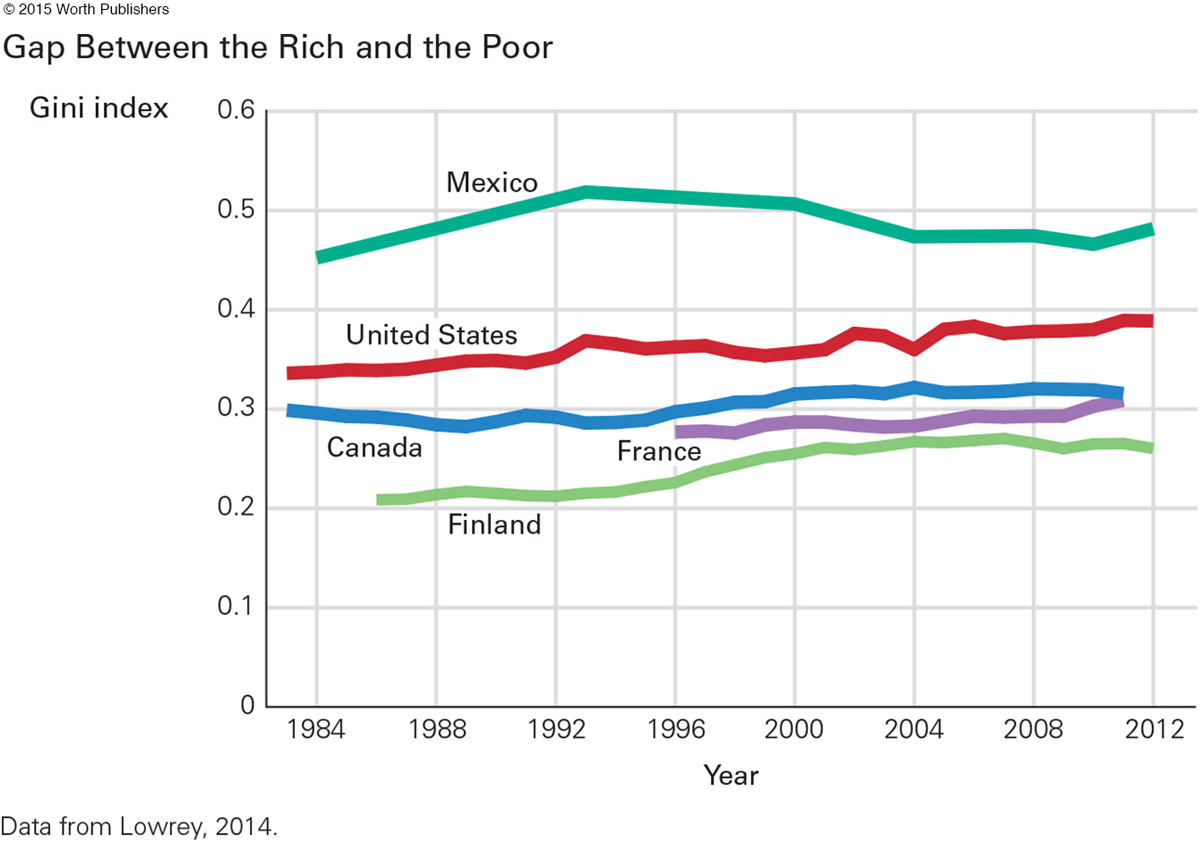

As you see, income alone does not define SES, especially when the historical context is considered. In the United States, the poverty level was set in 1963 by calculating food costs and family size: A family of three is below the 2014 poverty threshold if its household income is less than $19,790 (in Alaska, $24,730).

This way of measuring poverty is less valid currently because food costs are not the most significant family expense: Housing and medical care may be. Ways to measure poverty are complex, especially internationally. The United Nations rates the United States and Canada as rich nations, but some people in those nations might disagree. Another way to measure poverty is to consider the gap between the richest and poorest citizens of a nation (see Figure 1.7). On this, the United States does not do well.

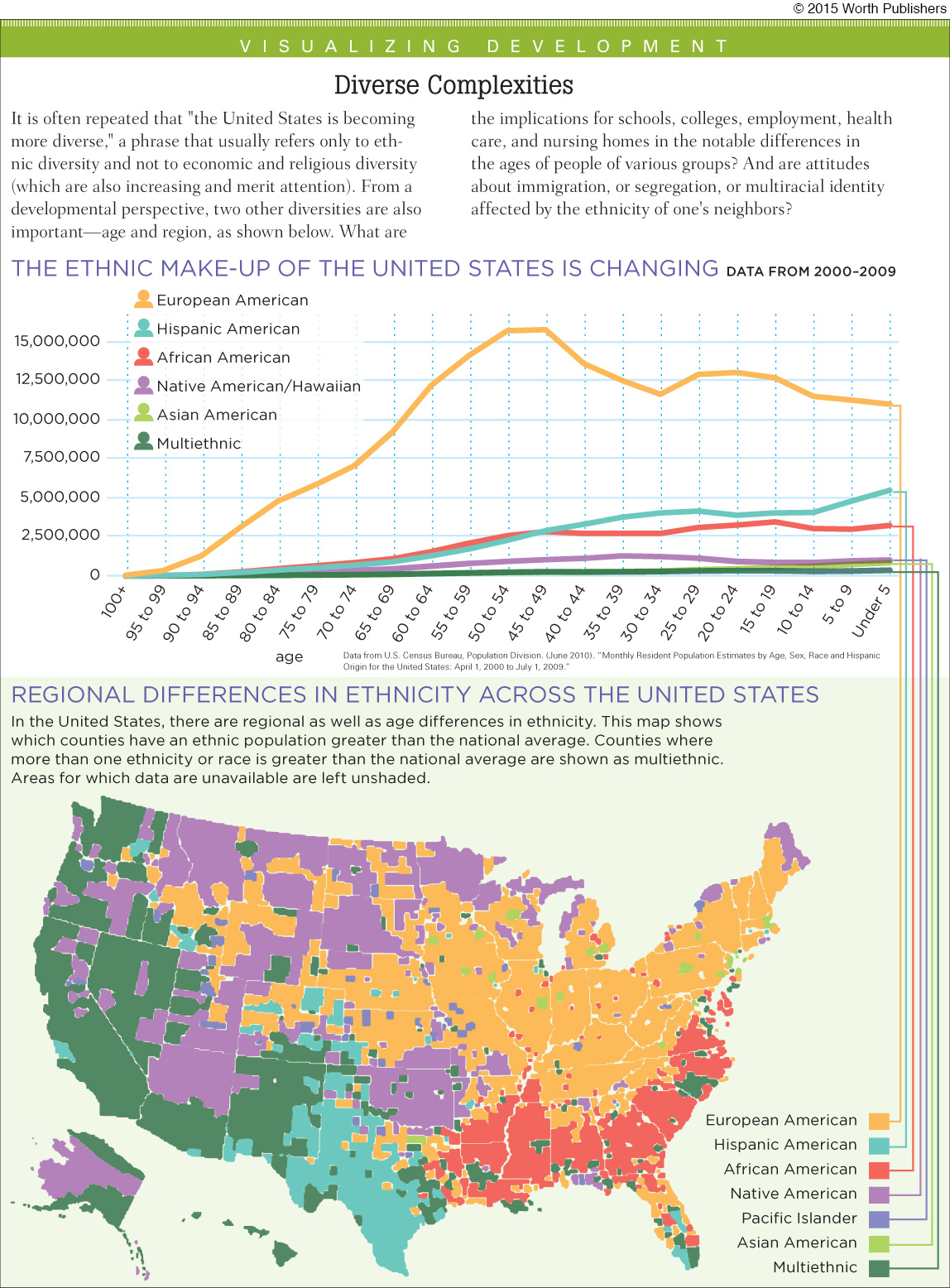

Every method of calculating poverty within North America finds that citizens whose ancestors were Hispanic or African rather than Asian or European are more often poor. A developmental trend is apparent as well: There are more poor children than adults, and more poor young adults than older adults.

SES brings advantages and disadvantages, opportunities and limitations—

THINK CRITICALLY: If the worst effects of poverty—

For example, Northern European nations eliminate SES disparities as much as possible. By contrast, the largest gaps between rich and poor tend to be in developing nations, especially in Latin America (Ravallion, 2014). Among advanced nations, the United States has “recently earned the distinction of being the most unequal of all developed countries” (Aizer & Currie, 2014, p. 856), not only by ethnic group but also by age—

Worldwide, abject poverty is less common than it was a few decades ago, but the rich are even richer than before. As one economist says, “the rising tide has indeed raised all boats . . . But the big yachts have done better, so overall income inequality is increasing” (Vanneman, quoted in Hvistendahl, 2014, p. 832).

Development Is Multi-Cultural

culture

A system of shared beliefs, norms, behaviors, and expectations that persist over time and prescribe social behavior and assumptions.

In order to study “all kinds of people, everywhere, at every age,” as developmental science does, it is essential that people of many cultures be considered. For social scientists, culture is “the system of shared beliefs, conventions, norms, behaviors, expectations and symbolic representations that persist over time and prescribe social rules of conduct” (Bornstein et al., 2011, p. 30).

Question 1.9

OBSERVATION QUIZ

How many children are sleeping here in this photograph?

Nine—

social construction

An idea that is built on shared perceptions, not on objective reality. Many age-

SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONS Thus, culture is far more than food, clothes, or rituals; it is a set of ideas that people share. This makes culture a powerful social construction, a concept constructed, or made, by a society. Social constructions affect how people think and behave as well as what they value, ignore, and punish.

Because culture is so basic to thinking and emotions, people are usually unaware that their values are socially constructed. Fish do not realize that they are surrounded by water; people do not realize that their assumptions about life and death arise from their own culture.

One assumption is evident if the word culture is used to refer to large groups of other people, as in “Asian culture” or “Hispanic culture.” That invites stereotyping and prejudice, since such large groups include people of many cultures. For instance, people from Korea and Japan are aware of notable cultural differences between their nationalities, as are people from Mexico and Guatemala.

In today’s United States, most people are influenced by several cultures, not just one. One observer contends that people with Jamaican heritage in the United States are tri-

To appreciate that culture is a matter of beliefs and values more than superficial differences, consider language. Of course, people speak distinct languages, but that in itself is not a cultural difference, although language may reflect culture. However, certain slang words and phrases signal cultural differences: Some people are offended by words that other people proudly say. That is cultural.

Watch Video: Interview with Barbara Rogoff to learn more about the role of culture in the development of Mayan children in Guatemala.

More generally, among some English-

One of my students remembered:

My mom was outside on the porch talking to my aunt. I decided to go outside; I guess I was being nosey. While they were talking I jumped into their conversation which was very rude. When I realized what I did it was too late. My mother slapped me in my face so hard that it took a couple of seconds to feel my face again.

[C., personal communication]

Notice how my student reflects her culture; she labels her own behavior “nosey” and “very rude.” She later wrote that she expects children to be seen but not heard and that her own son makes her “very angry” when he interrupts. Whether you agree depends on your culture.

difference-

The mistaken belief that a deviation from some norm is necessarily inferior to behavior or characteristics that are more typical.

DEFICIT OR JUST DIFFERENCE? Whatever a person’s culture or cultures may be, humans tend to believe that they, their nation, their group, and their culture are better than others. That belief becomes destructive if it reduces respect and appreciation. Developmentalists recognize the difference-

Negative judgments are often made about how other people raise children, or worship God, or even eat. Age differences are also stereotyped. Have you heard adults complain about the attitudes, abilities, or actions of teenagers, or of senior citizens? Such age stereotypes are evidence of judging a difference as a deficit.

Gender differences are another easy example. We are amused when young girls say, “Boys stink,” or their male classmates say, “Girls are stupid.” However, even though the sexes have far more similarities than differences, humans of all ages tend to notice differences and then make sexist judgments.

According to one scholar, even neuroscientists make that mistake. They are susceptible to “neurosexism,” seeing and explaining gender differences “in the absence of data” (Fine, 2014, p. 915).

One of the very few proven gender differences is that women are more tenderhearted and men more sexually driven (Hyde, 2014). If you are male, do you think that women are weak because they are too emotional; if you are female, do you think men are too obsessed with sex? If you answer yes, how human of you. And how mistaken.

Video: Research of Geoffrey Saxe

The difference-

Sometimes a difference is actually an asset (Marschark & Spencer, 2003). For example, cultures that discourage dissent also foster harmony. The opposite is also true—

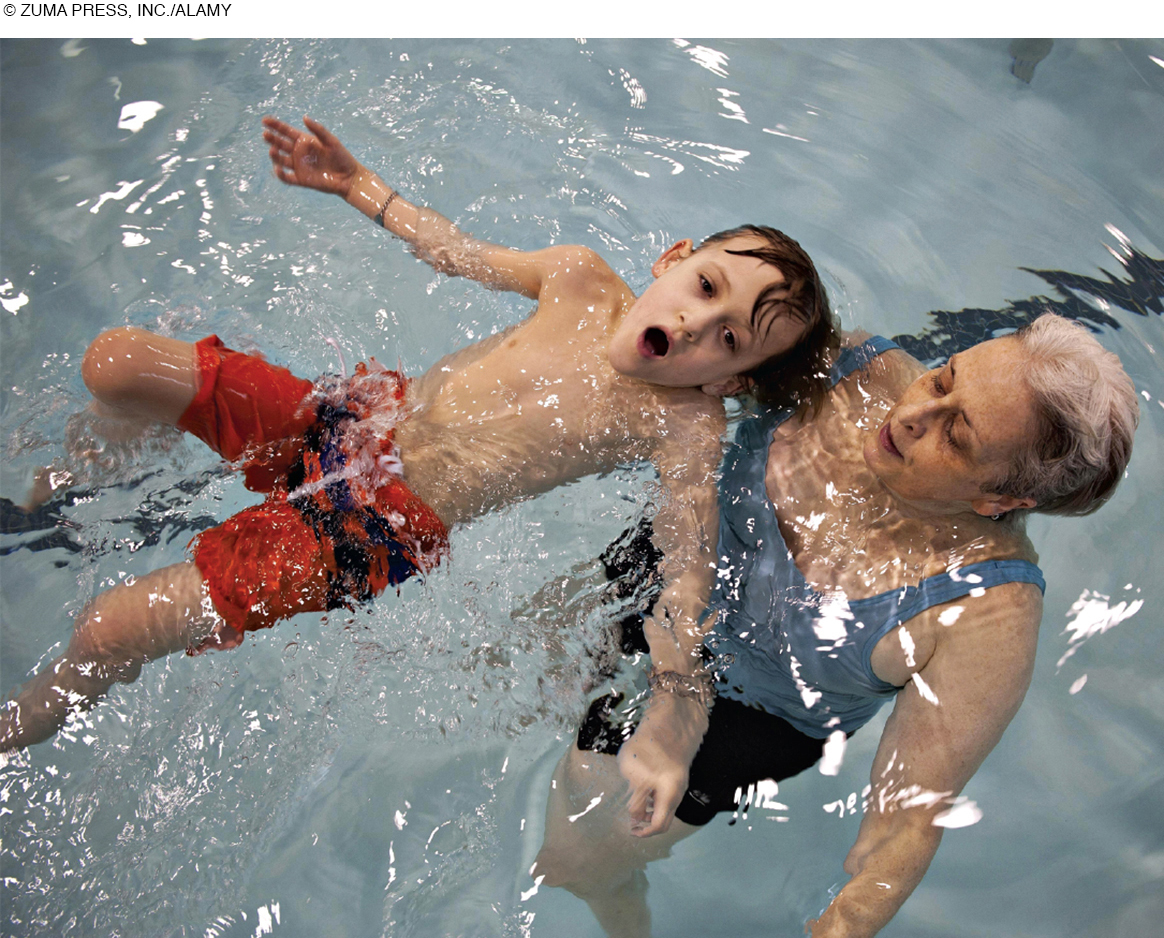

LEARNING WITHIN A CULTURE Russian developmentalist Lev Vygotsky (1896–

Vygotsky (discussed in more detail in Chapter 5) believed that guided participation is a universal process used by mentors to teach cultural knowledge, skills, and habits. Guided participation can occur via school instruction but more often happens informally, through “mutual involvement in several widespread cultural practices with great importance for learning: narratives, routines, and play” (Rogoff, 2003, p. 285).

ethnic group

People whose ancestors were born in the same region and who often share a language, culture, and religion.

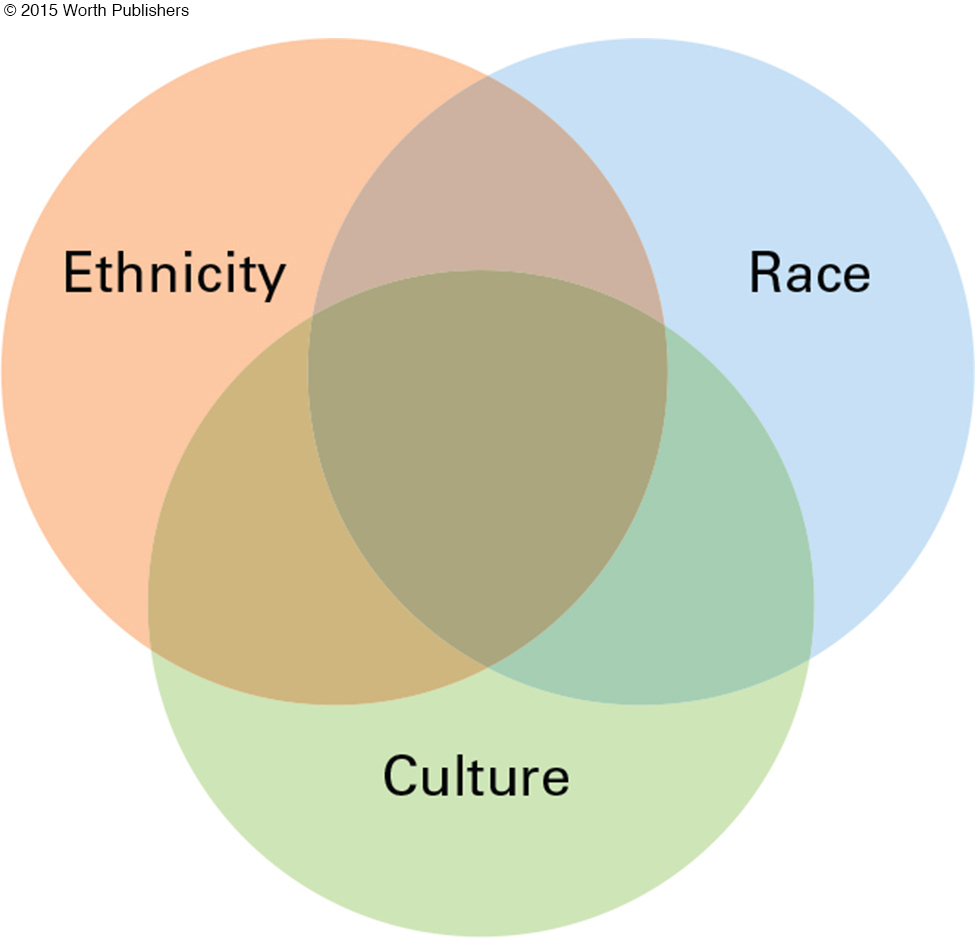

ETHNIC AND RACIAL GROUPS It is easy to confuse culture, ethnicity, and race because these terms sometimes overlap (see Figure 1.8). People of an ethnic group share certain attributes, almost always including ancestral heritage and usually national origin, religion, and language (Whitfield & McClearn, 2005). That means that ethnic groups often share a culture, but this is not a requirement. Some people of a particular ethnicity differ culturally (consider people of Irish descent in Ireland, Australia, and North America), and some cultures include people of several ethnic groups (consider British culture).

Ethnic groups are primarily social constructions, dependent on context. For example, African-

Race is also a social construction—

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

*

Using the Word Race

race

A group of people who are regarded by themselves or by others as distinct from other groups on the basis of physical appearance, typically skin color. Social scientists think race is a misleading concept, as biological differences are not signified by outward appearance.

The term race is used to categorize people via physical markers, particularly outward appearance. Historically, most North Americans believed that race was the outward manifestation of inborn biological differences. Fifty years ago, races were categorized by skin color: white, black, red, and yellow (Coon, 1962).

It is obvious now, but was not a few decades ago, that no one’s skin is white (like this page) or black (like these letters) or red or yellow. Social scientists consider race a social construction. They contend that color terms were used to exaggerate differences in skin tones.

Genetic analysis confirms that the biological concept of race is inaccurate. Although most genes are identical in every human, those few genetic differences that distinguish one person from another are poorly indexed by appearance (Race, Ethnicity, and Genetics Working Group, 2005).

Skin color is particularly misleading because dark-

Race is more than a flawed concept; it is a destructive one. Slavery, lynching, and segregation were directly connected to the conviction that race was inborn. Racism continues today in less obvious ways (some highlighted later in this book), impeding the goal of our study—

Since race is a social construction that leads to racism, some social scientists believe that the term should be abandoned (Gilroy, 2000). It is no longer used in many nations. A study of 141 nations found that 85 percent never use the word race on their census forms (Morning, 2008). Only in the United States does the census still distinguish between race and ethnicity, stating that Hispanics “may be of any race.”

Because of the way human cognition works, such labels encourage stereotyping (Kelly et al., 2010). As one scholar explains:

The United States’ unique conceptual distinction between race and ethnicity may unwittingly support the longstanding belief that race reflects biological difference and ethnicity stems from cultural difference . . . [and] preclude understanding of the ways in which racial categories are also socially constructed.

[Morning, 2008, p. 255]

Perhaps to avoid racism, the word race should not be used.

But consider the opposite perspective (Bliss, 2012). In a society with a history of racial discrimination, reversing that cultural heritage may require recognizing race. Although race is a social construction, not a biological distinction, it is powerful nonetheless. Many medical, educational, and economic conditions—

Furthermore, particularly in adolescence, people who are proud of their racial identity are likely to achieve academically, resist drug addiction, and feel better about themselves (Crosnoe & Johnson, 2011; Zimmerman et al., 2013). To encourage racial pride, race may first need to be recognized.

Indeed, many social scientists argue that pretending that race does not exist allows racism to thrive (e.g., sociologists Marvasti & McKinney, 2011; anthropologist McCabe, 2011). Two political scientists studying criminal justice found that people who claim to be color-

According to some scholars, criticism of President Obama reveals racial prejudice, and uninformed anti-

THINK CRITICALLY: To fight racism, must race be named and recognized?

Development Is Plastic

Both brain and behavior are far more plastic than once was thought. The term plasticity denotes two complementary aspects of development: Human traits can be molded (as plastic can be), and yet people maintain a certain durability (as plastic does). This provides both hope and realism—

Plasticity is basic to our contemporary understanding of human development because it simultaneously incorporates two facts: People can change over time, and new behavior depends partly on what has already happened.

dynamic-

A view of human development as an ongoing, ever-

This is evident in the dynamic-

Question 1.10

OBSERVATION QUIZ

What country is this?

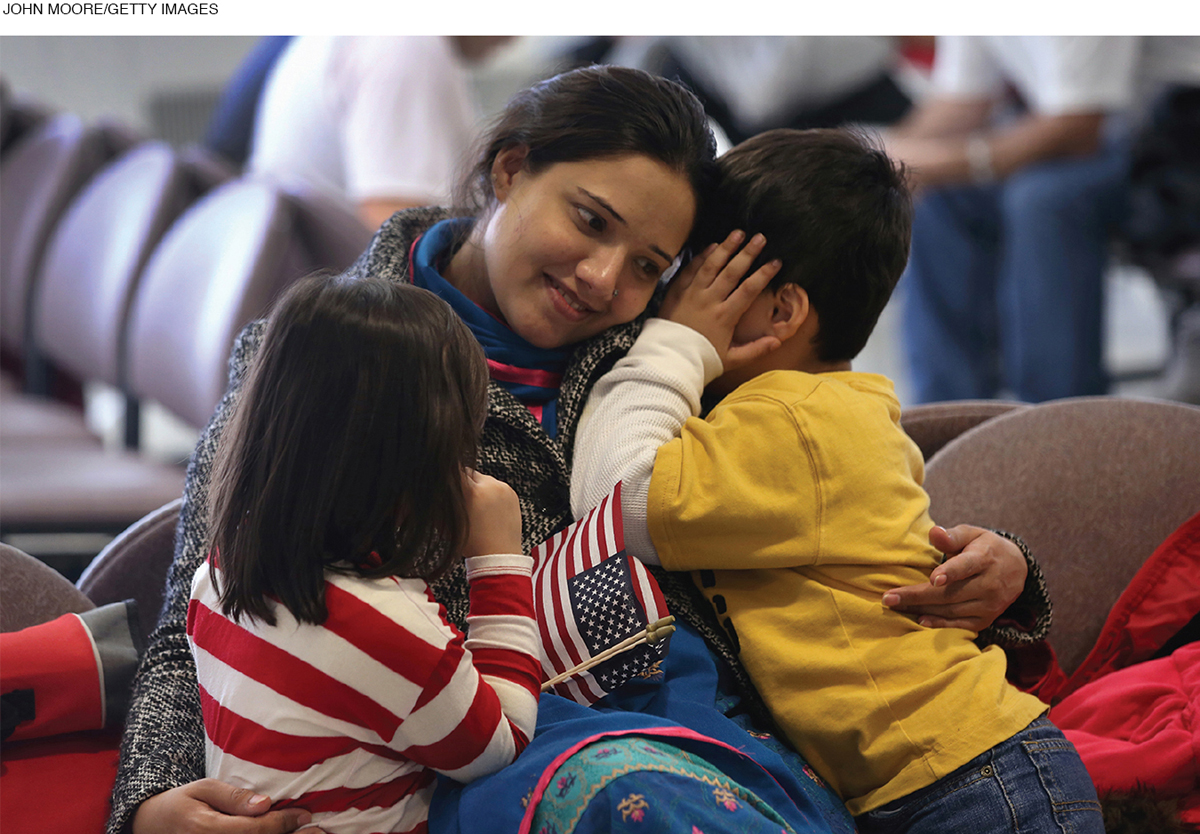

The three Somali girls wearing headscarves may have thrown you off, but these first-

Note the word dynamic: Physical contexts, emotional influences, the passage of time, each person, and every aspect of the ecosystem are always interacting, always in flux, always in motion. For instance, a useful strategy for developing motor skills in children with autism spectrum disorder (described in Chapter 7) is to think of the dynamic systems that undergird movement—

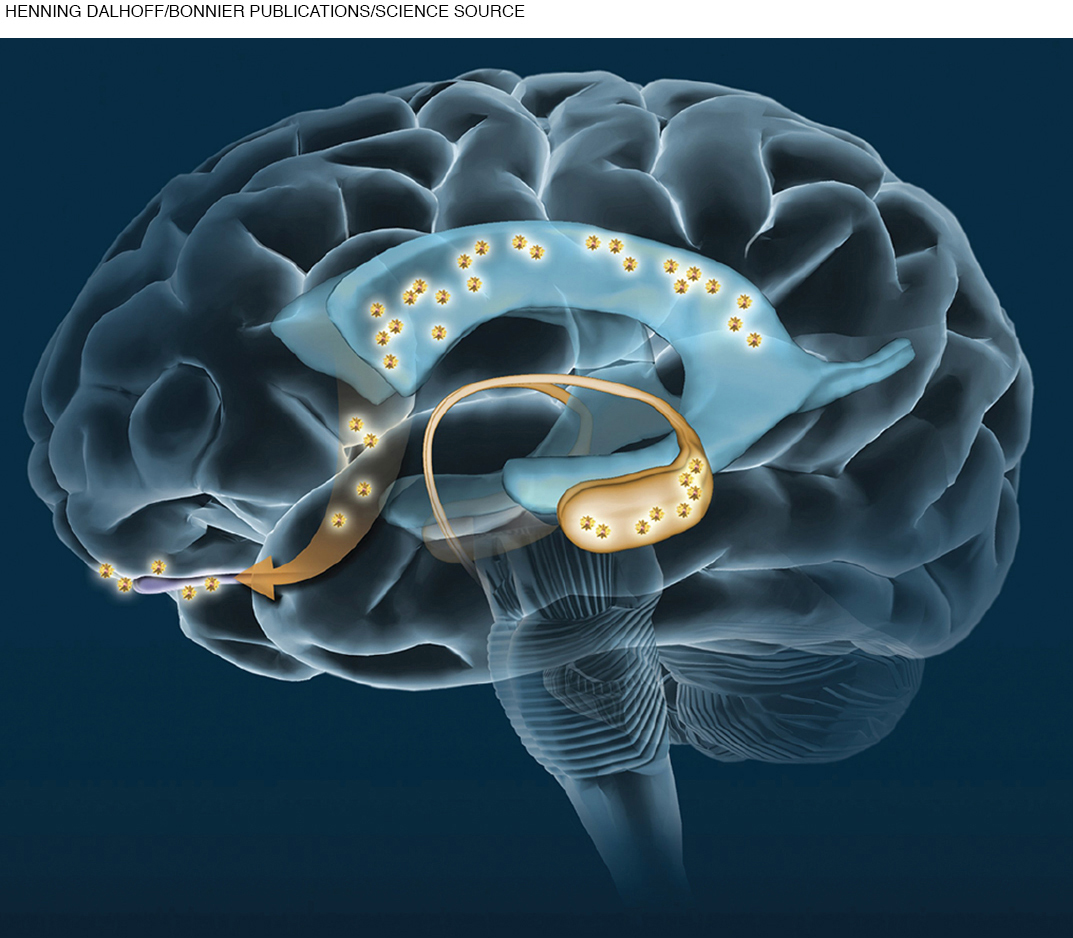

The most surprising example of plasticity in recent years involves the brain. Expansion of neurological structures, networks of communication between one cell and another, and even creation of neurons (brain cells) occurs in adulthood. This neurological plasticity is evident in hundreds of studies mentioned later in this text (see Figure 1.9).

Plasticity is especially useful when anticipating growth of a particular person: Everyone is constrained by past circumstances, but no one is confined by them. Consider David.

A CASE TO STUDY

*

My Nephew David

My sister-

Yet dire early predictions—

He attended regular public school, then the Kentucky School for the Blind, and then the University of Kentucky, earning a college degree. He then studied at an international school in Germany for translators. He relates well to his two older brothers (see photo) and especially to his two sisters-

Remember, plasticity cannot erase a person’s genes, childhood, or permanent damage. David’s disabilities are always with him (at age 46 he still lives with his mother). But his childhood experiences gave him lifelong strengths. His family loved and nurtured him, sending him to four preschools and then public kindergarten at age 6. By age 10, David had skipped a year of school and was a fifth-

David works as a translator, which he enjoys because “I like providing a service to scholars, giving them access to something they would otherwise not have.” As his aunt, I have seen him repeatedly defy predictions, evidence of plasticity. All four of the characteristics of the life-

|

Characteristic Multi- Multi- Multi- Plasticity. Every individual, and every trait within each individual, can be altered at any point in the life span. Change is ongoing, although neither random nor easy. |

Application in David’s Story David’s development seemed static (or even regressive, as when early surgery destroyed one eye) but then accelerated each time he entered a new school or college. The high SES of David’s family made it possible for him to receive good medical and educational care. His two older brothers protected him. Appalachia, where David and his family lived, has a particular culture, including acceptance of people with disabilities and willingness to help families in need. Those aspects of that culture benefited David and his family. David’s measured IQ changed from about 40 (severely mentally retarded) to about 130 (far above average), and his physical disabilities became less crippling as he matured. Nonetheless, because of a virus contracted before he was born, his entire life will never be what it might have been. |

Plasticity emphasizes that people can and do change, that predictions are not always accurate. Three insights already explained have improved predictions: (1) Nature and nurture always interact. (2) Certain ages are sensitive periods for particular kinds of development. (3) Genes predispose people to respond to certain circumstances, in differential susceptibility.

This was apparent for David: His inherited characteristics (from his smart parents) affected his ability to learn, his four preschools in early childhood (a sensitive period for language) helped him lifelong, and his inborn temperament (he is still devastated by criticism but overjoyed by praise) helped him flourish because he was easily influenced by his parents’ devoted guidance. If I had known more about human development when he was born with multiple disabilities, I would have predicted a brighter—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 1.11

1. How can both continuity and discontinuity be true for human development?

Development is multi-

Question 1.12

2. What are some of the contexts of your life?

Development takes place within many contexts, including one’s physical surroundings (climate, noise, population density, etc.) and family configurations (married couple, single parent, cohabiting couple, extended family, etc.).

Question 1.13

3. How does the exosystem affect children’s schooling?

Exosystems (community structures, and local educational, medical, employment, and communications systems) influence microsystems, which intimately and immediately shape human development. In this example, the school’s structure and administration (the exosystem) influence a child’s classroom and teacher (the microsystem), which intimately and immediately shape his or her development.

Question 1.14

4. What are some cohort differences between your generation and the one of your parents?

Answers can include (but are not limited to) the values, events, technologies, and culture of each era.

Question 1.15

5. What factors comprise a person’s SES (socioeconomic status)?

Answers can include (but are not limited to) income, occupation, education, neighborhood, and family size.

Question 1.16

6. Can you think of an example (not one in the book) of a social construction?

Stereotypes—

Question 1.17

7. What is the difference between race and ethnicity?

The term race has been used to categorize people on the basis of physical differences, particularly outward appearance. Ethnicity is a different social construction, affected by the social context rather than a direct outcome of biology.

Question 1.18

8. How does a culture pass on values to the next generation, according to Vygotsky?

Vygotsky believed mentors use the universal process of guided participation to teach children cultural knowledge, skills, and habits. Guided participation often happens informally, through mutual involvement in several widespread cultural practices with great importance for learning: narratives, routines, and play.

Question 1.19

9. In what two contrasting ways is human development plastic?

The term plasticity denotes two complementary aspects of development: Human traits can be molded (as plastic can be), and yet people maintain a certain durability of identity (as plastic does).

Question 1.20

10. What is implied when human development is described as dynamic?

Human development is an ongoing, ever-