Problems and Solutions

The early days of prenatal life place the developing person on a path toward health and success—

We now look at specific problems that may occur and how to prevent or minimize them. Always remember dynamic systems—

Abnormal Genes and Chromosomes

Video: Genetic Disorders

Perhaps half of all zygotes have serious abnormalities of their chromosomes or genes. Usually they never grow or implant. However, some such zygotes survive, grow, develop, and are born to live a satisfying life.

Question 2.19

OBSERVATION QUIZ

How many characteristics can you see that indicate that Daniel has Down syndrome?

Individuals with Down syndrome vary in many traits, but visible here are five common ones. Compared to most children his age, including his classmate beside him, Daniel has a rounder face, narrower eyes, shorter stature, larger teeth and tongue, and—

NOT EXACTLY 46 As you know, each sperm or ovum usually has 23 chromosomes, creating a zygote with 46 chromosomes and eventually a person. However, cells do not always split exactly in half to make gametes, partly because of the age of the parents—

If an entire chromosome is missing or added, that leads to a recognizable syndrome, a cluster of distinct characteristics that tend to occur together. Usually the cause is three chromosomes at a particular location instead of the usual two (a condition called a trisomy).

Down syndrome

A condition in which a person has 47 chromosomes instead of the usual 46, with three rather than two chromosomes at the 21st position. People with Down syndrome typically have distinctive characteristics, including unusual facial features (thick tongue, round face, slanted eyes), heart abnormalities, and language difficulties. (Also called trisomy-

The most common survivor with 47 chromosomes is a person with Down syndrome. This syndrome is also called trisomy-

Some 300 distinct characteristics may result from that third chromosome 21, usually including a thick tongue, round face, slanted eyes, hearing problems, heart abnormalities, muscle weakness, and short stature. Intellectual development is often slow. Family context, educational efforts, and possibly medication can decrease the harm (Kuehn, 2011).

The other common miscount involves the sex chromosomes. Every human has at least 44 autosomes and one X chromosome; an embryo cannot develop without those 45. However, about 1 in every 500 infants is born with only one sex chromosome (no Y) or with three or more (not just two). Having an odd number of sex chromosomes impairs cognition and sexual maturation. Specifics depend on exactly which chromosomes are at that 23rd site (XYY, XXX, XO, and so on) as well as epigenetics (Hong & Reiss, 2014).

GENE DISORDERS Everyone carries alleles that could produce serious diseases or handicaps in the next generation. The phenotype is affected only when the inherited gene is dominant or when both parents carry the same recessive gene and the zygote inherits the harmful gene from both, or when a particular combination of genes from both parents triggers a problem.

Serious dominant disorders are rare, because those who have them rarely live to become parents. However, a few dominant disorders do not affect the person until adulthood.

Adult onset occurs with Huntington’s disease, a fatal central nervous system disorder caused by a copy number variation—

Recessive diseases are more common, because people are often unaware that they are carriers, and being a carrier may confer some benefit. About 1 in 12 North American men and women carries an allele for cystic fibrosis, thalassemia, or sickle-

Consider the most studied example: sickle-

Almost every genetic disease is more common in one group than in another (Weiss & Koepsell, 2014). About 11 percent of Americans with African ancestors are carriers of the sickle-

Each nation targets the genetic disorders that are common among its citizens. In the United States, people with cystic fibrosis or sickle-

fragile X syndrome

A genetic condition that involves the X chromosome and that causes slow development.

Some recessive conditions are X-

Harm to the Fetus

The early days of life place the developing fetus on the path toward health and success—

teratogen

Any agent or condition, including viruses, drugs, and chemicals, that can impair prenatal development, resulting in birth defects or complications.

The cascade may begin before a woman realizes she is pregnant, as many toxins, illnesses, and experiences can cause harm early in pregnancy. Every week, scientists discover an unexpected teratogen, which is anything—

behavioral teratogens

Agents and conditions that can harm the prenatal brain, impairing the future child’s intellectual and emotional functioning.

Many teratogens cause no physical defects but affect the brain, making a child hyperactive, antisocial, or learning-

I was nine years old when my mother announced she was pregnant. I was the one who was most excited. . . . My mother was a heavy smoker, Colt 45 beer drinker and a strong caffeine coffee drinker.

One day my mother was sitting at the dining room table smoking cigarettes one after the other. I asked, “Isn’t smoking bad for the baby?” She made a face and said, “Yes, so what?”

I asked, “So why are you doing it?”

She said, “I don’t know.”. . .

During this time I was in the fifth grade and we saw a film about birth defects. My biggest fear was that my mother was going to give birth to a fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) infant. . . . My baby brother was born right on schedule. The doctors claimed a healthy newborn. . . . Once I heard healthy, I thought everything was going to be fine. I was wrong, then again I was just a child. . . .

My baby brother never showed any interest in toys. . . . [H]e just cannot get the right words out of his mouth. . . . [H]e has no common sense. . . .

Why hurt those who cannot defend themselves?

[J., personal communication]

As you remember from Chapter 1, one case proves nothing. J. blames her mother, although genes, postnatal experiences, and lack of preventive information and services may be part of the cascade as well. Nonetheless, J. rightly wonders why her mother took the risk.

EVALUATING RISKS Risk analysis is crucial in human development (Sheeran et al., 2014). Although all teratogens increase the risk, none always causes damage. Risk analysis involves probabilities, not certainties (Aven, 2011).

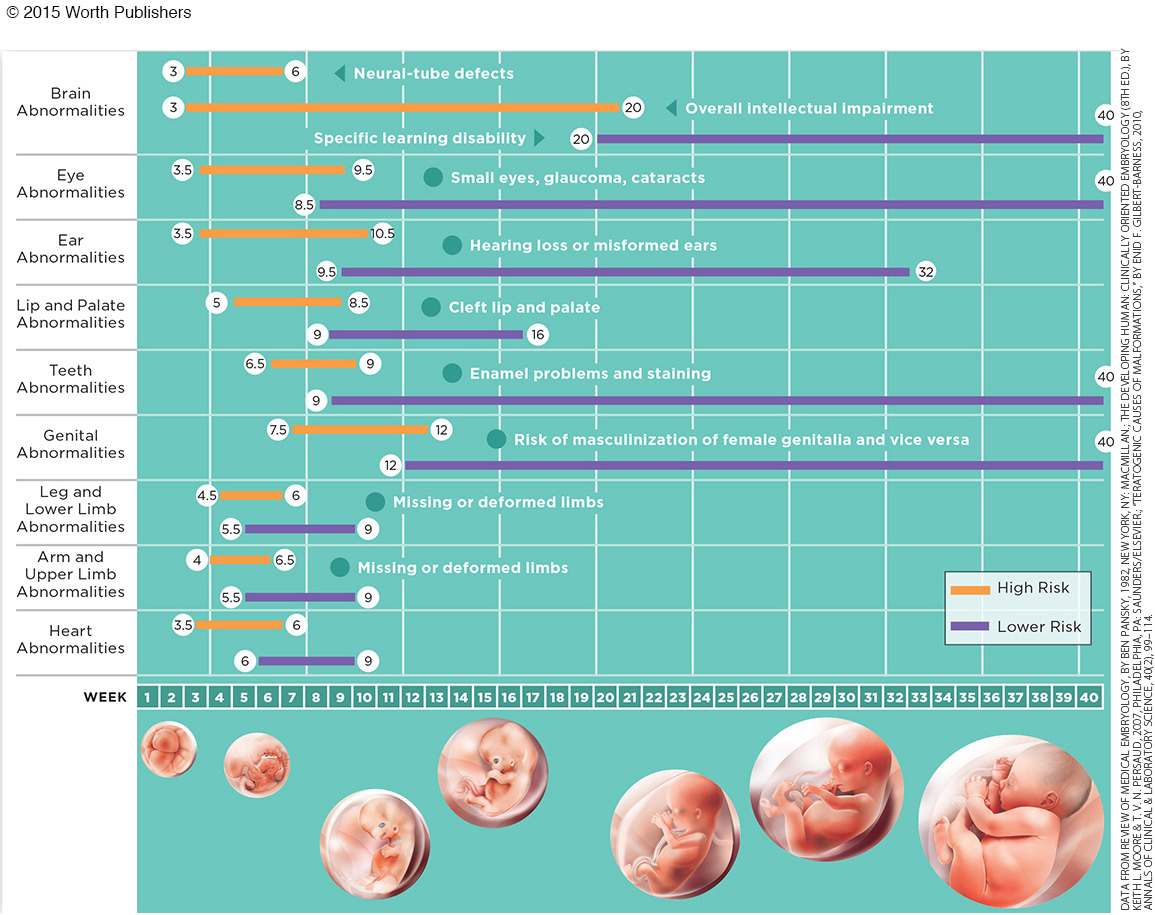

For both risk and protection, timing may be crucial. The first days and weeks after conception (the germinal and embryonic periods) are the critical period for body formation, and the final months are important for body weight. Health during the entire fetal period affects the brain (see Figure 2.7).

Obstetricians recommend that before pregnancy occurs, women should avoid drugs (especially alcohol), supplement a balanced diet with extra folic acid and iron, update their immunizations, and gain or lose weight if needed. Indeed, preconception health is at least as important as postconception health (see Table 2.4).

threshold effect

A situation in which a certain teratogen is relatively harmless in small doses but becomes harmful once exposure reaches a certain level (the threshold).

A second crucial factor is the dose and/or frequency of exposure. Some teratogens have a threshold effect; they are harmless until exposure reaches a certain level, at which point they “cross the threshold” and become damaging. This threshold is not a fixed boundary: Dose, timing, frequency, and other teratogens affect when the threshold is crossed (O’Leary et al., 2010).

|

What Prospective Mothers Should Do

|

What Prospective Mothers Really Do (U.S. Data)

|

Data from Bombard et al., 2013; MMWR, July 20, 2012; Brody, 2013; Mosher et al., 2012; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, December, 2012.

Experts rarely specify thresholds, partly because one teratogen may affect the threshold of another. Alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana are more teratogenic, with a lower threshold for each, when all three are combined.

fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS)

A cluster of birth defects, including abnormal facial characteristics, slow physical growth, and intellectual disabilities, that may occur in the child of a woman who drinks alcohol while pregnant.

Is there a safe dose for psychoactive drugs? Perhaps, but, as my student asked, why risk it? Consider alcohol. During the early weeks, heavy drinking can cause fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), distorting facial features (especially the eyes, ears, and upper lip). Later in pregnancy, alcohol is a behavioral teratogen. One longitudinal study of 7-

Genes are a third factor that influences the effects of teratogens. When a woman carrying dizygotic twins drinks alcohol, for example, the twins’ blood alcohol levels are equal; yet one twin may be protected because alleles for the enzyme that metabolizes alcohol may differ. Differential susceptibility is evident (McCarthy & Eberhart, 2014).

The Y chromosome makes male fetuses more vulnerable. They are more likely to be spontaneously aborted or stillborn and more likely to be harmed by teratogens than female fetuses are. This is true overall, but the male/female hazard rate differs from one teratogen to another (Lewis & Kestler, 2012).

Maternal genes may be important during pregnancy. One allele results in low levels of folic acid in a woman’s bloodstream. Her deficiency, via the placenta, affects the embryo, which may develop neural-

Neural-

Video Activity: Teratogens explores the factors that enable or prevent teratogens from harming a developing fetus.

MAKING PREDICTIONS Results of teratogenic exposure cannot be predicted precisely in individual cases, although impact can be measured for the population, as evident with neural-

General health is protective. Women who maintain good nutrition and avoid drugs and teratogenic chemicals (often in pesticides, cleaning fluids, and cosmetics) usually have healthy babies. Some medications are necessary (e.g., for women with epilepsy, diabetes, and severe depression), but consultation should begin before conception.

Many women assume that herbal medicines or over-

Even doctors are not always careful. Opioids (narcotics) to reduce pain may harm the fetus, and aspirin may cause excessive bleeding during birth. Yet one study found that 23 percent of pregnant women on Medicaid receive a prescription for a narcotic (Desai et al., 2014).

Some doctors do not ask women if they are taking psychoactive drugs. For example, one Maryland study found that almost one-

Women of all ages consult the Internet regarding medications in pregnancy. However, a study of 25 Web sites found that only 103 of the 235 medications listed as safe had been evaluated by TERIS (a respected national panel of teratologists). Further, of those 103, only 60 were considered safe. The rest were not proven harmful, but the experts said that more evidence was needed (Peters et al., 2013). Sometimes the same drug was on the safe list of one Internet site and the danger list of another.

A CASCADE OF RISK Even when evidence seems clear, the proper response is controversial. Pregnant women can be arrested and jailed for using alcohol or other psychoactive drugs in six states (Minnesota, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Wisconsin).

Alicia Beltran, 14 weeks pregnant in Wisconsin, told her doctor that she had been addicted to pills but quit before she became pregnant, as confirmed by urine tests. The doctor ordered her to take anti-

Several women have been jailed when their newborns had illegal substances in their bloodstream (Eckholm, 2013). Such measures may do more harm than good if they make women avoid prenatal care or hospital births.

Every pregnancy and birth has multiple risks, so it is a mistake to blame any problem solely on the mother, or the doctor, or the community.

cerebral palsy

A disorder that results from damage to the brain’s motor centers. People with cerebral palsy have difficulty with muscle control, so their speech and/or body movements are impaired.

anoxia

A lack of oxygen that, if prolonged, can cause brain damage or death.

For instance, cerebral palsy (a disease marked by difficulties with movement) was once thought to be caused by birth procedures, such as forceps misused by the doctor. However, we now know that cerebral palsy results from genetic sensitivity, teratogens, and/or maternal infection (Mann et al., 2009), worsened by anoxia (insufficient oxygen) to the fetal brain at birth.

Anoxia itself is part of a cascade. Normal birth involves moments of low oxygen, as evident from the fetal heart rate. How long anoxia can continue without harming the brain depends on genes, birthweight, gestational age, drugs in the bloodstream (either taken by the mother before birth or given during birth), and much else. Thus, anoxia is part of a cascade that may cause cerebral palsy. Likewise, almost every complication is the result of many factors.

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Conflicting Advice

Pregnant women want to know about the thousands of drugs, chemicals, and diseases that cause fetal harm. However, the scientific method is designed to be cautious. It takes years for longitudinal research, testing of alternative hypotheses, and replication before solid conclusions are reached. Only after this process did all scientists agree on such (now obvious) teratogens as rubella and cigarettes.

One current dispute is whether pesticides should be allowed on the large farms that produce most of the fruits and vegetables for consumption in the United States. No biologist doubts that pesticides harm frogs, fish, and bees, but the pesticide industry insists that careful use (e.g., spraying on plants, not workers) does not harm people.

Developmentalists, however, worry that pregnant women who breathe these toxins might have children with brain damage. As one scientist said, “Pesticides were designed to be neurotoxic . . . Why should we be surprised if they cause neurotoxicity?” (Lanbhear, quoted in Mascarelli, 2013, p. 741).

For example, umbilical cord blood proves that many fetuses are exposed to chlorpyrifos, a pesticide. Longitudinal research finds that these children have lower intelligence and more behavior problems than other children (Horton et al., 2012).

However, Dow Chemical Company, which sells the pesticide, argues that the research does not take into account confounding factors, such as the living conditions of farmworkers’ children (Mascarelli, 2013). If a child who lives in a shack and attends a different school every few months has learning disabilities, does it matter whether his mother worked in the fields with pesticides when she was pregnant?

The U.S. government has banned chlorpyrifos from household use (it once was commonly used to kill roaches and ants), but it is still used in agriculture and in homes in other nations. In this dispute, developmentalists choose to protect the fetal brain, which is why this chapter advises pregnant women to avoid pesticides. Is that overly cautious?

On many other possible teratogens, developmentalists themselves are conflicted. Fish consumption is an example.

Pregnant women in the United States are told to eat less fish, but those in the United Kingdom are told to eat more fish. The reason for these opposite messages is that fish contains mercury (a teratogen) and DHA (an omega-

To make all this more difficult, pregnant women are, ideally, happy and calm: Stress and anxiety affect the fetus. Pregnancy often increases fear and anxiety (Rubertsson et al., 2014); scientists do not want to add to the worry. Prospective parents want clear, immediate answers, yet scientists cannot always provide them.

Prenatal Testing

Seeing a medical professional in the first trimester has many benefits: Women learn what to eat, what to do, and what to avoid. Some serious conditions, syphilis and HIV among them, can be diagnosed and treated before they harm the fetus. Prenatal tests (of blood, urine, and fetal heart rate as well as ultrasound) reassure parents, facilitating the crucial parent–

In general, early care protects fetal growth, makes birth easier, and renders parents better able to cope. When complications appear (such as twins, gestational diabetes, and infections), early recognition increases the chance of a healthy birth.

Unfortunately, however, about 20 percent of early pregnancy tests raise anxiety instead of reducing it. It is now possible to use a simple blood test to indicate many chromosomal and genetic problems. The mother may learn information that she does not want to know (de Jong et al., 2015). Couples may argue about risks that they never discussed before.

false positives

The result of a laboratory test (blood, urine or sonogram) that suggests an abnormality that is not present.

One specific example comes from a test in place for decades: alpha-

A CASE TO STUDY

False Positives and False Negatives

John and Martha, both under age 35, were expecting their second child. Martha’s initial prenatal screening revealed low alpha-

Another blood test was scheduled. . . .

John asked, “What exactly is the problem?” . . .

“We’ve got a one in eight hundred and ninety-

John smiled, “I can live with those odds.”

“I’m still a little scared.”

He reached across the table for my hand. “Sure,” he said, “that’s understandable. But even if there is a problem, we’ve caught it in time. . . . The worst-

“I might have to have an abortion?” The chill inside me was gone. Instead I could feel my face flushing hot with anger. “Since when do you decide what I have to do with my body?”

John looked surprised. “I never said I was going to decide anything,” he protested. “It’s just that if the tests show something wrong with the baby, of course we’ll abort. We’ve talked about this.”

“What we’ve talked about,” I told John in a low, dangerous voice, “is that I am pro-

“You used to be,” said John.

“I know I used to be.” I rubbed my eyes. I felt terribly confused. “But now . . . look, John, it’s not as though we’re deciding whether or not to have a baby. We’re deciding what kind of baby we’re willing to accept. If it’s perfect in every way, we keep it. If it doesn’t fit the right specifications, whoosh! Out it goes.”. . .

John was looking more and more confused. “Martha, why are you on this soapbox? What’s your point?”

“My point is,” I said, “that I’m trying to get you to tell me what you think constitutes a ‘defective’ baby. What about . . . oh, I don’t know, a hyperactive baby? Or an ugly one?”

“They can’t test for those things and—

“Well, what if they could?” I said. “Medicine can do all kinds of magical tricks these days. Pretty soon we’re going to be aborting babies because they have the gene for alcoholism, or homosexuality, or manic depression. . . . Did you know that in China they abort a lot of fetuses just because they’re female?” I growled. “Is being a girl ‘defective’ enough for you?”

“Look,” he said, “I know I can’t always see things from your perspective. And I’m sorry about that. But the way I see it, if a baby is going to be deformed or something, abortion is a way to keep everyone from suffering—

“. . . And what is it,” I said softly, more to myself than to John, “what is it that people do? What do we live to do, the way a horse lives to run?”

[Beck, 2011, pp. 134–

The second AFP test was in the normal range, “meaning that there was no reason to fear . . . Down syndrome” (p. 142). John and Martha no longer discussed abortion.

The opposite of a false positive is a false negative, a mistaken assurance that all is well. Amniocentesis revealed that the second AFP was a false negative. Their fetus had Down syndrome after all. John and Martha had another angry discussion, and Martha decided to give birth to Adam, who has Down syndrome. Years later they had a third child. When Adam was in early adolescence, Martha and John divorced.

Low Birthweight

low birthweight (LBW)

A body weight at birth of less than 5½ pounds (2,500 grams).

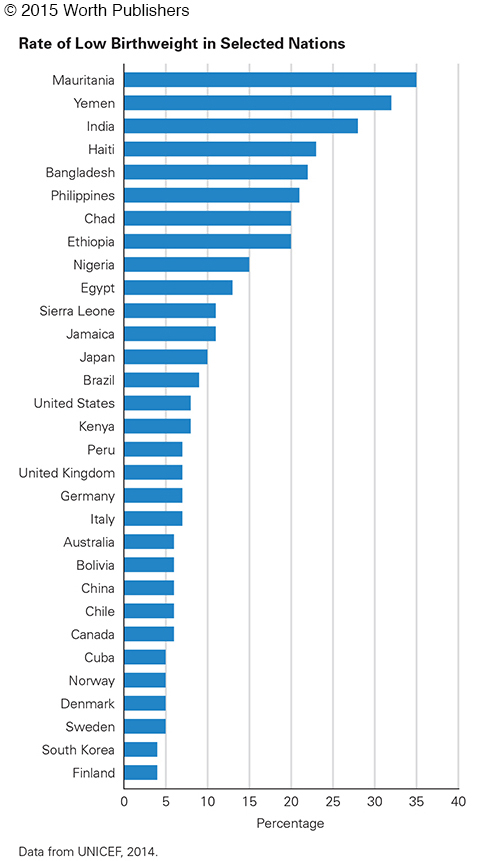

As you just read, small and immature newborns are more vulnerable to every teratogen and birth complication. The international cutoff for low birthweight (LBW)is 2,500 grams (5½ pounds). UNICEF estimated that 22 million low-

very low birthweight (VLBW)

A body weight at birth of less than 3 pounds, 5 ounces (1,500 grams).

extremely low birthweight (ELBW)

A body weight at birth of less than 2 pounds, 3 ounces (1,000 grams).

Some LBW babies are very low birthweight (VLBW), under 1,500 grams (3 pounds, 5 ounces), and extremely low birthweight (ELBW), under 1,000 grams (2 pounds, 3 ounces). It is possible for a newborn to weigh as little as 500 grams. They are the most vulnerable: Half of them die even with excellent care, and none of them live without it (Lau et al., 2013).

preterm birth

A birth that occurs three or more weeks before the full 38 weeks of the typical pregnancy have elapsed—

Remember that fetal weight normally doubles in the last trimester of pregnancy, with most of that gain occurring in the final three weeks. Thus, a baby born preterm (three or more weeks early, no longer called premature) is usually, but not always, LBW.

small for gestational age (SGA)

Having a body weight at birth that is significantly lower than expected, given the time since conception. For example, a 5-

In addition, some fetuses gain weight slowly throughout pregnancy and are small-

CAUSES OF LOW BIRTHWEIGHT Maternal or fetal illness might cause SGA or preterm birth, but maternal drug use is a more common cause. Every psychoactive drug slows fetal growth, with tobacco implicated in 25 percent of all LBW newborns worldwide.

Another common reason for slow growth and preterm birth is malnutrition. Women who begin pregnancy underweight, who eat poorly during pregnancy, or who gain less than 3 pounds (1.3 kilograms) per month in the last six months more often have underweight infants.

Unfortunately, many risk factors—

Watch Video: Low Birthweight in India, which discusses the causes of LBW among babies in India.

The causes of low birthweight just mentioned rightly focus on the pregnant woman. However, fathers—

immigrant paradox

The surprising fact that immigrants tend to be healthier than U.S. born residents of the same ethnicity. This was first evident among immigrant births to Mexican Americans. Such births are less often low birth weight than the non-

The role of the social network is most apparent in what is called the immigrant paradox. Many immigrants have difficulty getting education and well-

Thus, immigrants should birth more LBW babies. But, paradoxically, their babies are generally healthier in every way, including in weight, than newborns of native-

This was first called the Hispanic paradox because, although U.S. residents born in Mexico or South America average lower SES than people of Hispanic descent born in the United States, their newborns have fewer problems. The same paradox has been found for immigrants from the Caribbean, Africa, eastern Europe, and Asia. The crucial factor may be fathers and grandmothers, who keep pregnant immigrant women healthy and drug-

Newborns of Chinese descent born in the United States are an interesting case. If their mothers’ socioeconomic status is low, newborns weigh more and are less likely to die if their mothers were born in China, not in the United States. However, if the mother is college-

This suggests that maternal education, household income, and social support all protect prenatal health. Of the three, social support may be most crucial, but the other two are important as well.

CONSEQUENCES OF LOW BIRTHWEIGHT You have already read that life itself is uncertain for the smallest newborns. Ranking worse than most developed nations—

For survivors born underweight, every developmental accomplishment—

Longitudinal research from many nations finds that children who were at the extremes of SGA or preterm have many neurological problems in middle childhood, including smaller brain volume, lower IQs, and behavioral difficulties (Clark et al., 2013; Hutchinson et al., 2013; van Soelen et al., 2010). Even in adulthood, risks persist: Adults who were LBW are more likely to develop diabetes and heart disease.

Longitudinal data provide both hope and caution. Remember that risk analysis gives probabilities, not certainties—

COMPARING NATIONS In some northern European nations, only 4 percent of newborns weigh under 2,500 grams; in several South Asian nations, including India, Pakistan, and the Philippines, more than 20 percent are that small. Worldwide, far fewer low-

Some nations, China and Chile among them, have improved markedly (Hellerstein et al., 2015). In many nations, community health programs emphasize prenatal health. That helps, according to a study provocatively titled Low birth weight outcomes: Why better in Cuba than Alabama? (Neggers & Crowe, 2013).

In some nations, notably in sub-

THINK CRITICALLY: Food scarcity, drug use, and unmarried parenthood have all been suggested as reasons for the LBW rate in the United States. Which is it—

There are some encouraging data: The U.S. low-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 2.20

1. What are the consequences if an infant is born with trisomy-

Most people born with trisomy-

Question 2.21

2. Why are some recessive traits (such as sickle-

The reason is evolutionary—

Question 2.22

3. How does the timing of exposure to a teratogen affect the risk of harm to the fetus?

Some teratogens cause damage only during a critical period of development. For example, rubella can cause blindness and deafness if the exposure occurs during the embryonic period; if later (in the first or second trimester), exposure can cause brain damage.

Question 2.23

4. How do genes increase or decrease risk to a fetus?

Genes can influence the effects of teratogens. For example, the Y chromosome makes male fetuses more vulnerable. They are more likely to be spontaneously aborted or stillborn and more likely to be harmed by teratogens than female fetuses are. Maternal genes may be important during pregnancy. One allele results in low levels of folic acid in a woman’s bloodstream. Her deficiency, via the placenta, affects the embryo, which may develop neural-

Question 2.24

5. What are the potential consequences of drinking alcohol during pregnancy?

Early in pregnancy, an embryo exposed to heavy drinking can develop fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which distorts the facial features, especially the eyes, ears, and upper lip. Later in pregnancy, alcohol is a behavioral teratogen, the cause of fetal alcohol effects (FAE), leading to hyperactivity, poor concentration, impaired spatial reasoning, and slow learning.

Question 2.25

6. What are the benefits of prenatal care?

Prenatal care can help keep mother and baby healthy. Doctors can spot health problems early when they see mothers regularly. This allows doctors to treat them early. Doctors also can talk to pregnant women about things they can do to give their unborn babies a healthy start to life.

Question 2.26

7. What are the differences among LBW, VLBW, and ELBW?

Low birthweight (LBW) is defined as weight less than 2,500 grams (5 pounds, 8 ounces). This group is further grouped into two subgroups: very low birthweight (VLBW), which is less than 1,500 grams (3 pounds, 5 ounces); and extremely low birthweight (ELBW), which is less than 1,000 grams (2 pounds, 3 ounces).

Question 2.27

8. What would cause a newborn to be LBW?

Being born preterm, maternal or fetal illness, maternal psychoactive drug use, and maternal malnutrition can all cause a baby to be LBW.

Question 2.28

9. What are the consequences of low birthweight in childhood and adulthood?

Many LBW infants are late in milestones such as smiling, holding a bottle, walking, and talking. Cognitive difficulties as well as visual and hearing impairments may emerge as time passes. Even in adulthood, some risks persist—