Growth in Infancy

In infancy, growth is so rapid and the consequences of neglect are so severe that gains are closely monitored. Length, weight, and head circumference should be measured monthly at first, and every organ should be checked to make sure it functions well.

Body Size

Video: Physical Development in Infancy and Toddlerhood offers a quick review of the physical changes that occur in a child’s first two years.

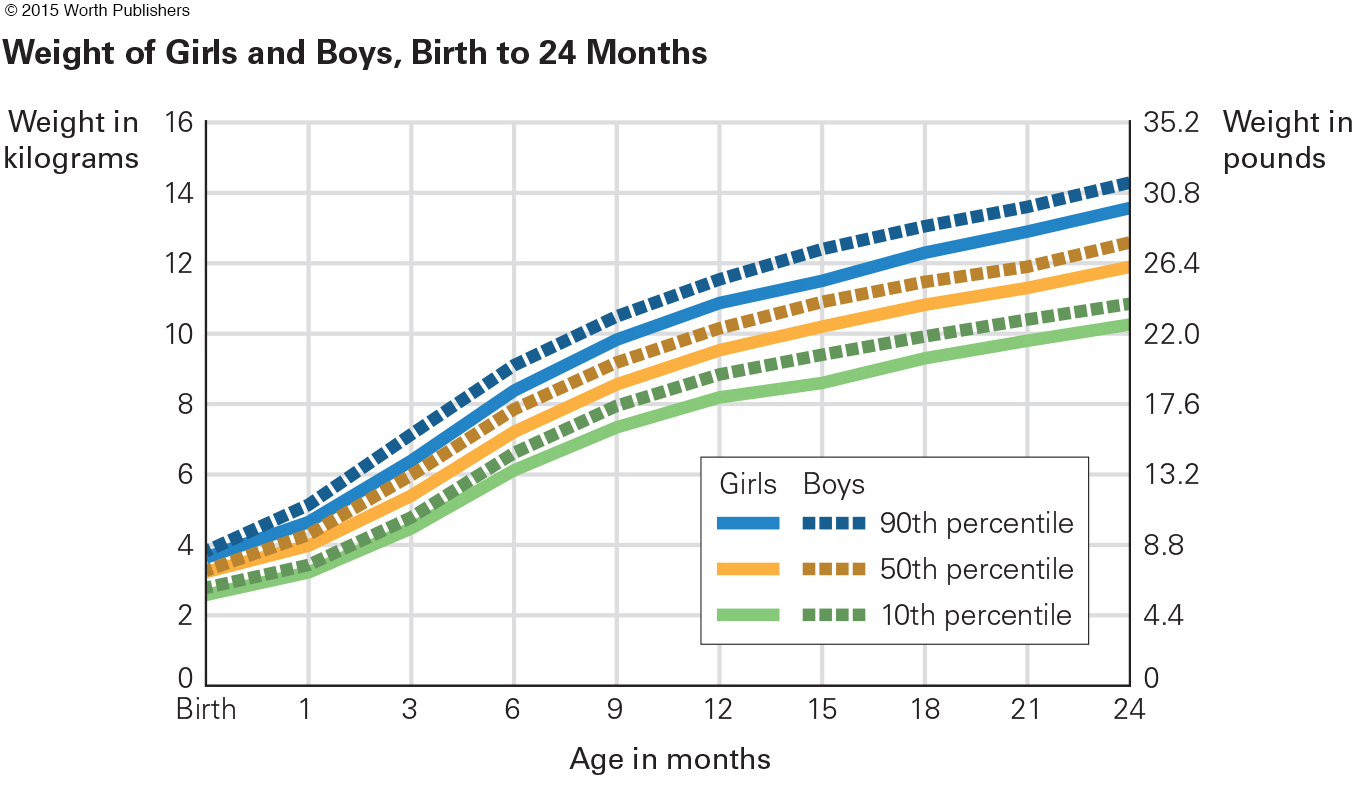

Weight gain is dramatic. Newborns lose weight in the first three days and then gain an ounce a day for several months. Birthweight typically doubles by 4 months and triples by a year. An average 7-

Physical growth in the second year is slower but still rapid. By 24 months, most children weigh almost 28 pounds (13 kilograms). They have added more than a foot in height—

norm

An average, or standard, calculated from many individuals within a specific group or population.

Each of these numbers is a norm, which is a standard, for a particular population. The “particular population” for the norms just cited is North American infants. Remember, however, that genetic diversity means that some perfectly healthy newborns from every continent are smaller or larger than these norms.

percentile

A point on a ranking scale of 0 to 100. The 50th percentile is the midpoint; half the people in the population being studied rank higher and half rank lower.

At each well-

For any baby, an early sign of trouble occurs when percentile changes markedly, either up or down. If an average baby moves from, say, the 50th to the 20th percentile, that could be the first sign of failure to thrive, which could be caused by dozens of medical conditions. Pediatricians consider it “outmoded” to blame parents for failure to thrive, but in any case the cause should be discovered, and remedied (Jaffe, 2011, p. 100).

Sleep

Throughout life, health and growth correlate with regular and ample sleep (Maski & Kothare, 2013). As with many health habits, sleep patterns begin in the first year.

Newborns sleep about 15 to 17 hours a day. Every week brings a few more waking minutes. For the first two months the norm for total time asleep is 14¼ hours; for the next 3 months, 13¼ hours; for the next 12 months, 12¾ hours. Remember that norms are averages; individuals vary. Parents report that, among every 20 infants in the United States, one sleeps nine hours or fewer per day and one sleeps 19 hours or more (Sadeh et al., 2009).

National averages vary as well. By age 2, the typical New Zealand toddler sleeps 15 percent more than the typical Japanese one (13 hours compared to 11

hours compared to 11 ) (Sadeh et al., 2010).

) (Sadeh et al., 2010).

Infants also vary in how long they sleep at a stretch. Preterm and breast-

REM (rapid eye movement) sleep

A stage of sleep characterized by flickering eyes behind closed lids. REM indicates dreaming.

Over the first months, the time spent in each type or stage of sleep changes. Babies born preterm may always seem to be dozing. About half the sleep of full-

Sleep varies not only because of biology (age and genes) but also because of culture and caregivers. Babies who are fed formula and cereal sleep longer and more soundly—

Parents are soon frustrated if they think their babies will adjust to adult sleep–

Overall, 25 percent of children under age 3 have sleeping problems, according to parents surveyed in an Internet study of more than 5,000 North Americans (Sadeh et al., 2009). Problems are especially common when the baby is the parents’ first child.

New parents “are rarely well-

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Where Should Babies Sleep?

Traditionally, most middle-

co-

A custom in which parents and their children (usually infants) sleep together in the same room.

bed-

When two or more people sleep in the same bed. If one of those people is an infant, some researchers worry that the adult will roll over on the infant.

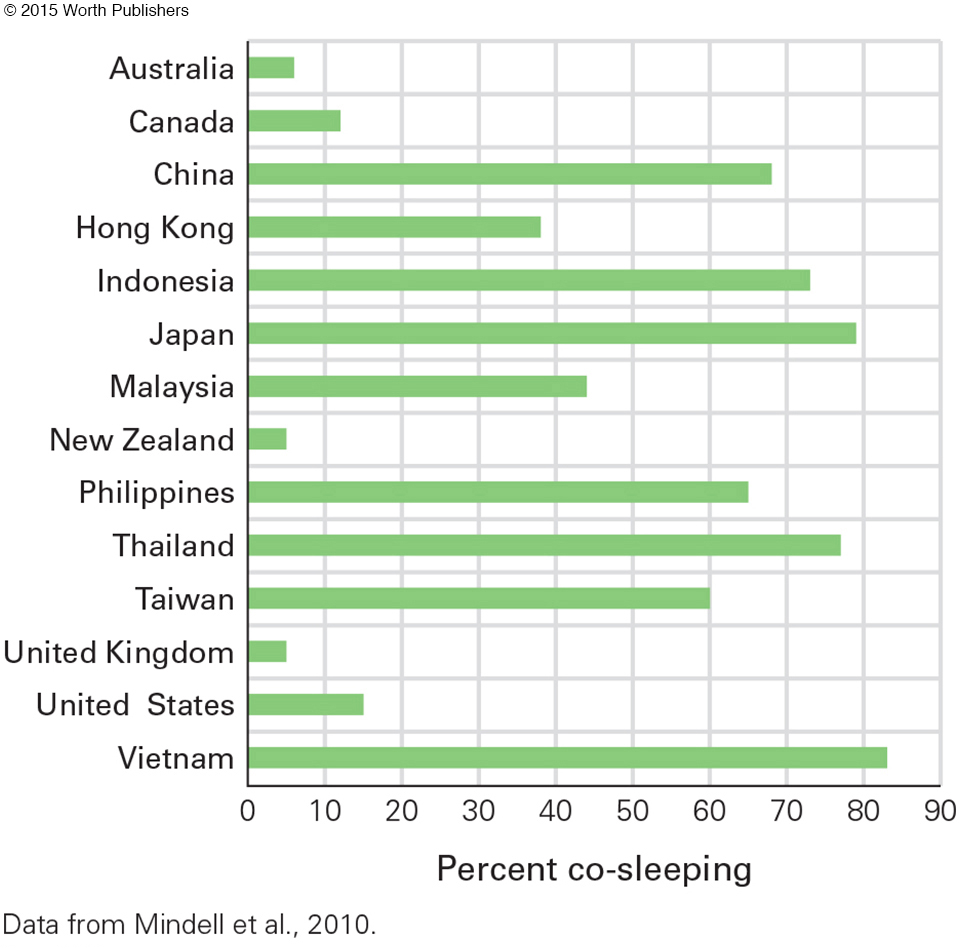

By contrast, most infants in Asia, Africa, and Latin America slept near their mothers, a practice called co-

Sleeping alone may encourage independence for both child and adult—

Many companies now sell “co-

A 19-

North Americans may attribute this international difference to poverty, since few families in poor nations have an extra room. Everywhere, mothers with higher SES are less likely to co-

In the United States the age of the baby is crucial. One study found that even infants in middle-

The authors of that study suggest that the correlation between maternal depression and co-

I take care of my baby at night, since my husband would never wake up until morning whatever happens. Babies, who cannot turn over yet, are at risk of suffocation and SIDS because they would not be able to remove a blanket by themselves if it covers over their face. In my case, I sleep with my older child and baby. By the way, my husband sleeps in a separate room because of his bad snoring.

[Shimizu et al., 2014]

Contrary to this woman’s rationalization, data from the United States find that sudden infant death (SIDS, discussed later) is twice as likely when babies sleep beside their parents. Researchers pinpoint one major reason: Many parents occasionally go to sleep after drinking or drugging. If their baby is beside them, bed-

Of course, if the baby is nearby but not beside the parent (co-

As one review explained, “There are clear reasons … [for bed-

Since both sides have good reasons, why such opposing perspectives? Perhaps past customs are the reason. Adults may be affected, not by logic or data, but by “ghosts in the nursery,” decades-

THINK CRITICALLY: Should some ghosts be welcomed and others banned?

Developmentalists recognize that this issue is “tricky and complex” (Gettler & McKenna, 2010, p. 77). The physical and psychological needs of many family members must be considered, with many options possible.

Brain Development

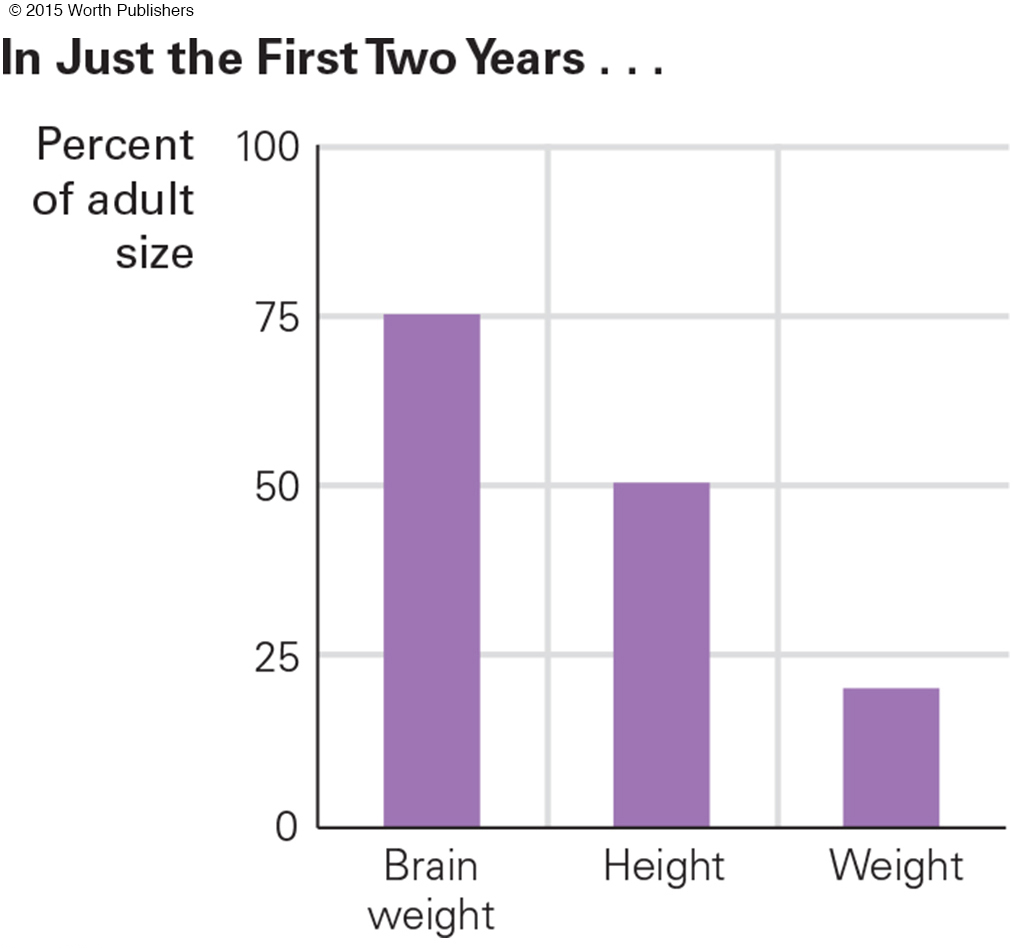

Prenatal and postnatal brain growth (measured by head circumference) is crucial for later cognition (Gilles & Nelson, 2012). From two weeks after conception to two years after birth, the brain grows more rapidly than any other organ, being about 25 percent of adult weight at birth and almost 75 percent at age 2 (see Figure 3.3). Over the same two years, brain circumference increases from about 14 to 19 inches.

head-

A biological mechanism that protects the brain when malnutrition disrupts body growth. The brain is the last part of the body to be damaged by malnutrition.

If teething or a stuffed-

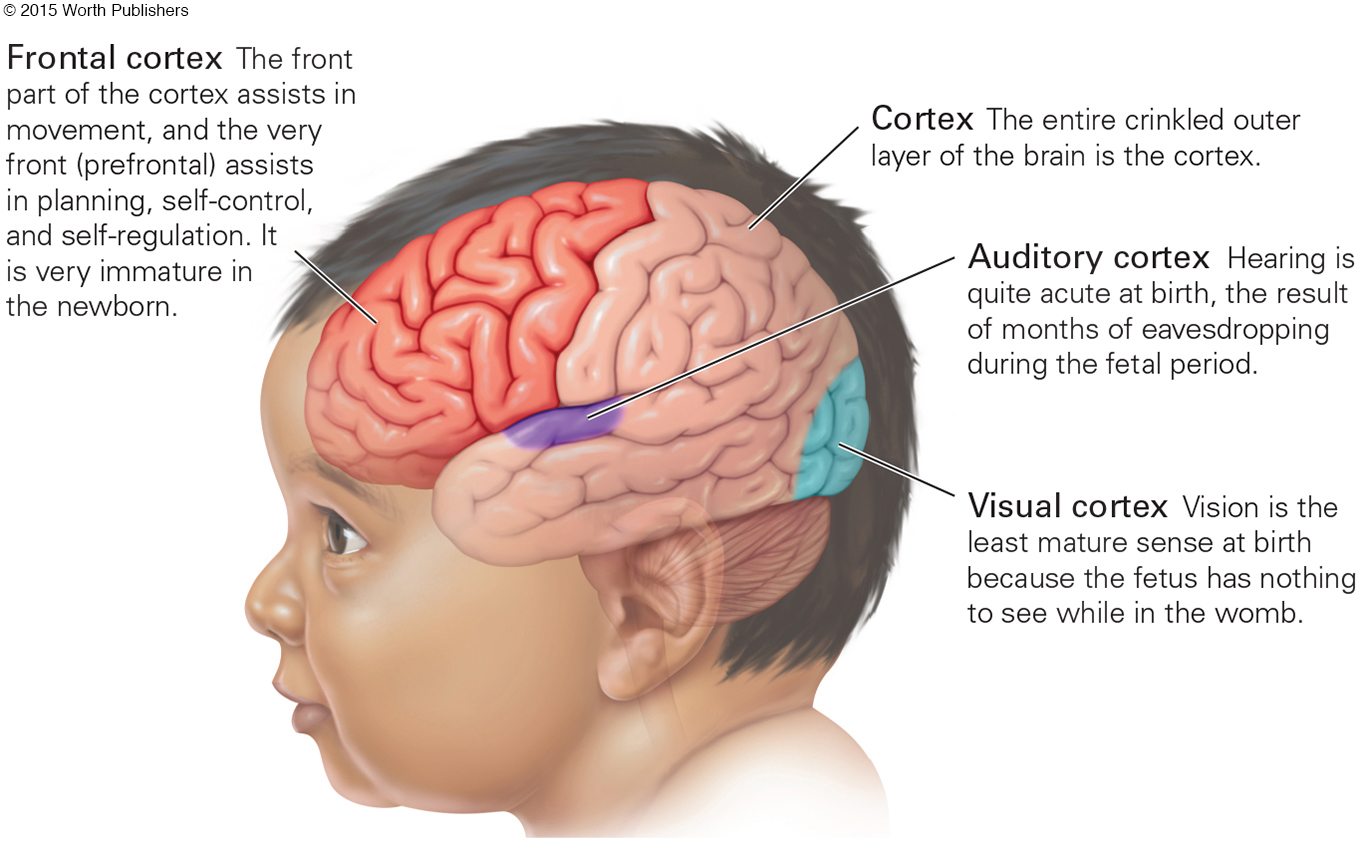

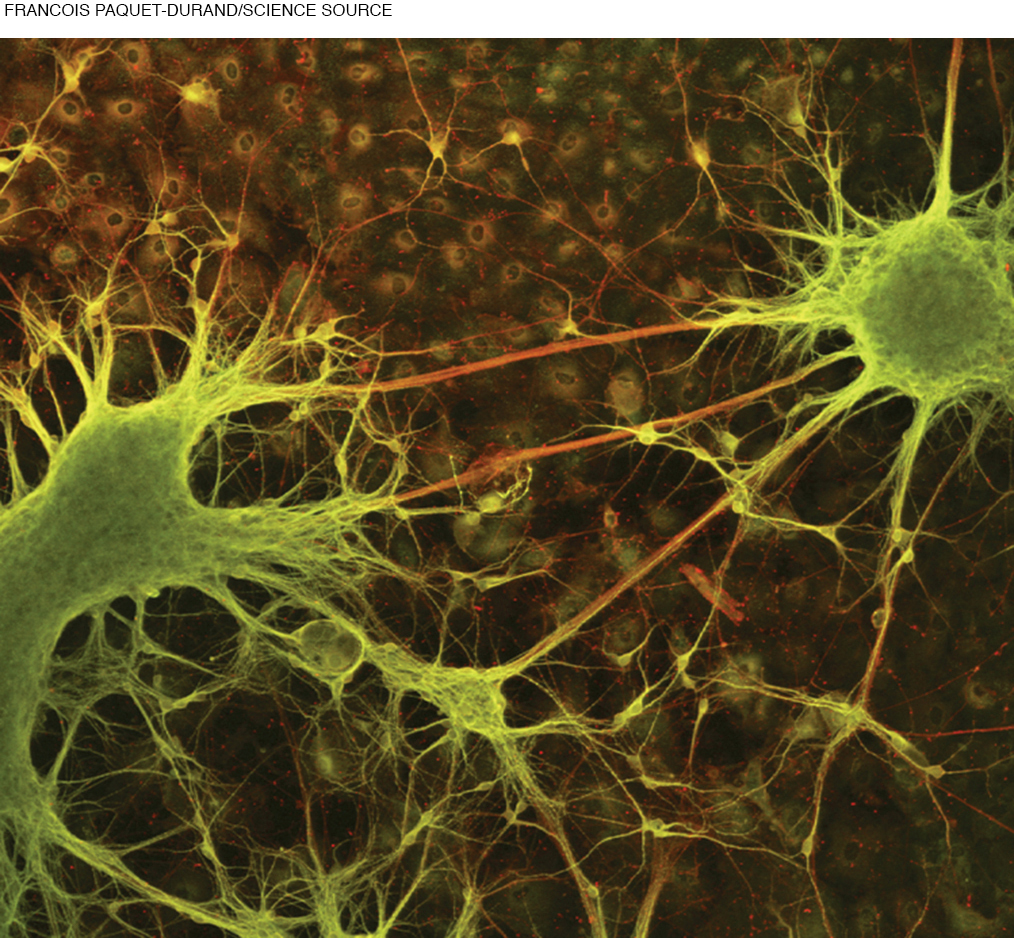

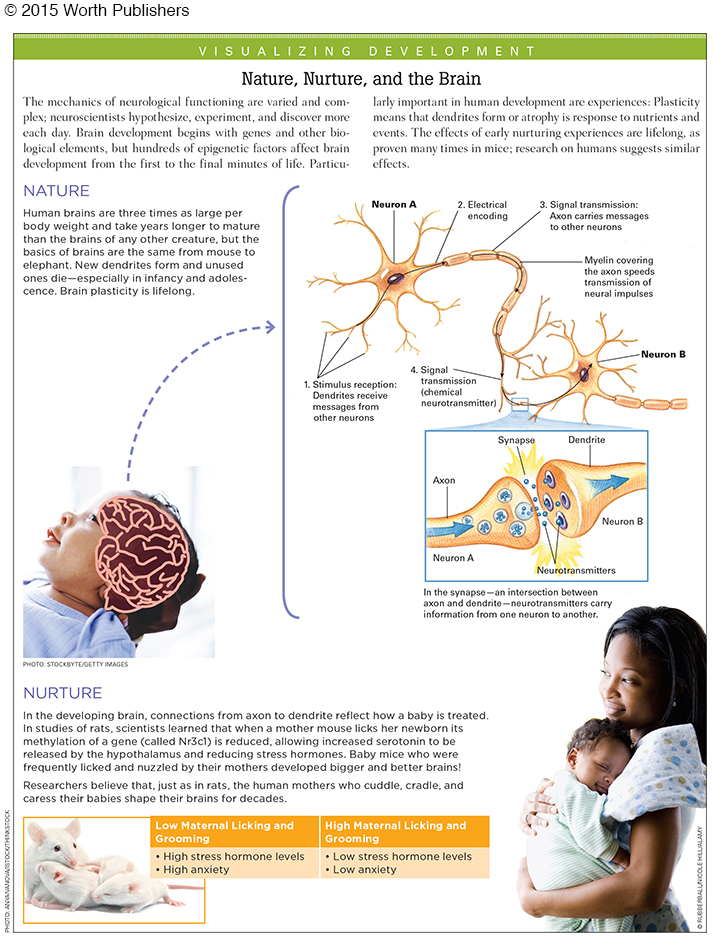

BRAIN BASICS Findings from neuroscience are discussed in every chapter of this book. We begin here with the basics—

neurons

Nerve cells in the central nervous system, especially in the brain.

cortex

The outer layers of the brain in humans and other mammals. Most thinking, feeling, and sensing involve the cortex.

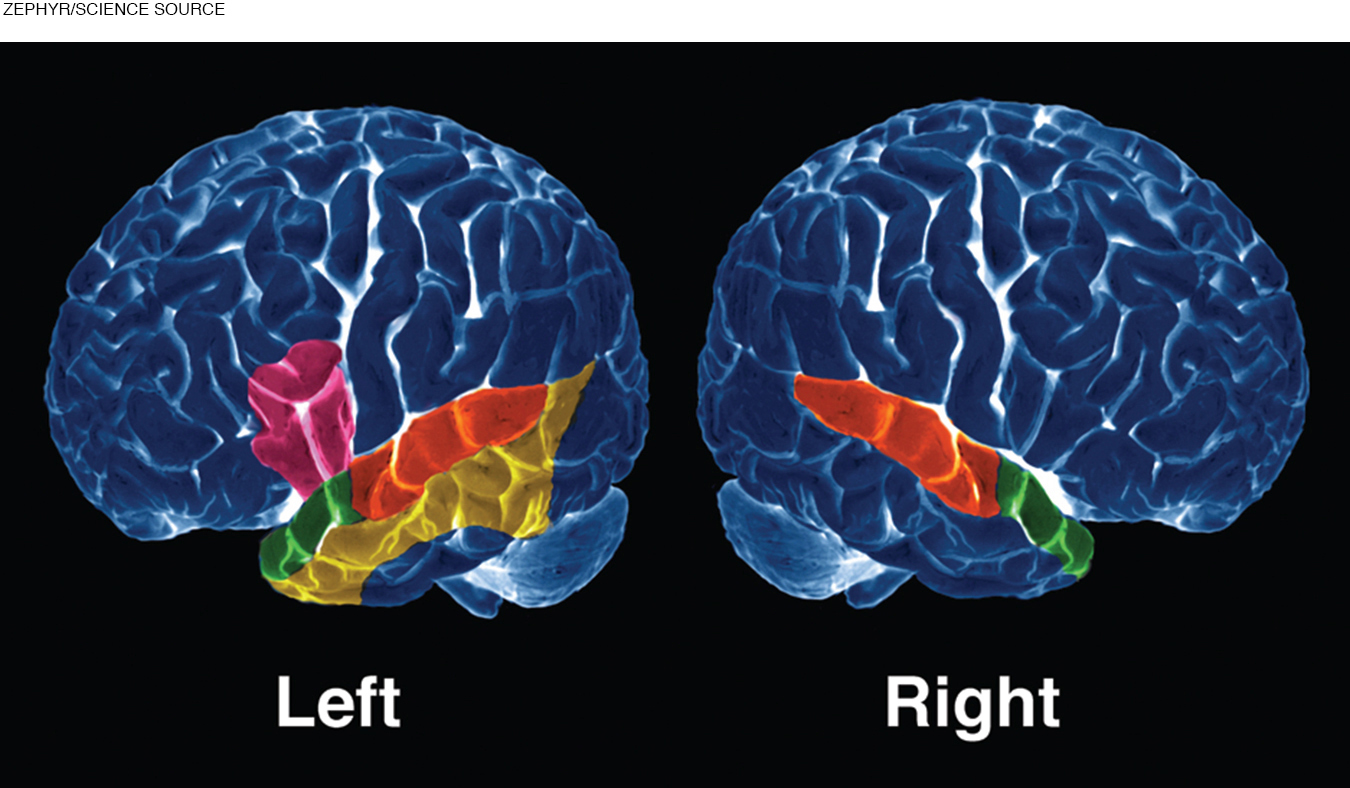

Communication within the central nervous system (CNS)—the brain and spinal cord—

prefrontal cortex

The area of the cortex at the very front of the brain that specializes in anticipation, planning, and impulse control.

The final part of the brain to mature is the prefrontal cortex, the area behind the forehead that is crucial for anticipation, planning, and impulse control. The prefrontal cortex is inactive in early infancy and gradually becomes more efficient in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, with marked variation from one person to another at every age (Walhovd et al., 2014).

axons

Fibers that extends from a neuron and transmits electrochemical impulses from that neuron to the dendrites of other neurons.

dendrites

Fibers that extend from neurons and receive electrochemical impulses transmitted from other neurons via their axons.

synapses

The intersection between the axon of one neuron and the dendrites of other neurons.

Neurons connect to other neurons via intricate networks of nerve fibers called axons and dendrites (see Visualizing Development below). Each neuron typically has a single axon and numerous dendrites, which spread out like the branches of a tree. The axon of each neuron reaches toward the dendrites of other neurons at intersections called synapses, which are critical communication links within the brain.

neurotransmitters

Brain chemicals that carry information from the axon of a sending neuron to the dendrites of a receiving neuron.

Axons and dendrites do not touch at synapses. Instead, the electrical impulses in axons cause the release of chemicals called neurotransmitters, which carry information from the axon of the sending neuron to the dendrites of the receiving neuron.

GROWTH AND PRUNING During the first months and years, rapid growth and refinement in axons, dendrites, and synapses occur, especially in the cortex. Dendrite growth is the main reason that brain weight triples from birth to age 2 (Johnson, 2011).

An estimated fivefold increase in dendrites in the cortex occurs in the 24 months after birth, with about 100 trillion synapses present at age 2. According to one expert, “40,000 new synapses are formed every second in the infant’s brain” (Schore & McIntosh, 2011, p. 502).

transient exuberance

The great but temporary increase in the number of dendrites that develop in an infant’s brain during the first two years of life.

pruning

When applied to brain development, the process by which unused connections in the brain atrophy and die.

Early dendrite growth is called transient exuberance: exuberant because it is rapid and transient because some is temporary. This expansive growth is followed by pruning. A gardener might prune a rose bush by cutting away some growth to enable more, or more beautiful, roses to bloom. Similarly, unused brain connections atrophy and disappear.

Pruning is beneficial. Indeed, insufficient pruning may be the reason that many toddlers with autism have heads that are larger than average; too many dendrites make them hypersensitive to sights and sounds, unable to tolerate social interaction (Lewis et al., 2013).

As one expert explains it, there is an

exuberant overproduction of cells and connections, followed by a several-

[Insel, 2014, p. 1727]

Notice the word sculpting, as if an artist created an intricate sculpture from raw marble or wood. Human infants are gifted sculptors, designing their brains for whatever family, culture, or society they happen to be born into, discarding the excess in order to think more clearly.

experience-

Brain functions that require certain basic common experiences (which an infant can be expected to have) in order to develop normally.

experience-

Brain functions that depend on particular, variable experiences and therefore may or may not develop in a particular infant.

Experiences sculpt the brain. Some sculpting is called experience-

Brain development is experience-

In contrast, certain facets of brain development are experience-

Depending on such variations, infant neurons connect in particular ways; some dendrites grow and others disappear (Stiles & Jernigan, 2010). In other words, every baby needs to develop language—

IMPLICATIONS FOR CAREGIVERS Most infants develop well within their culture. Head-

Playing with a young baby, allowing varied sensations, and encouraging movement (arm waving in the early months, walking later on) are all fodder for brain connections. Severe lack of stimulation (e.g., no talking at all) stunts the brain.

This does not mean that babies require spinning, buzzing, multitextured, and multicolored toys. In fact, such toys may be a wasted purchase since overstimulated babies may cry to avoid bombardment. Infants are fascinated by simple objects and exaggerated expressions. A mouth opening wide or making smacking sounds captures infant attention.

The slow development of the prefrontal cortex means that infants cannot yet plan, anticipate, or modify their emotions. Unless adults understand this, they might be angry with an infant who does not smile, or stop crying, or sleep when the adult wishes.

shaken baby syndrome

A life-

If a frustrated caregiver reacts to crying by shaking the baby, that can cause shaken baby syndrome, a life-

The Senses

Every sense functions at birth. Newborns have open eyes, sensitive ears, and responsive noses, tongues, and skin. Indeed, very young babies use all their senses to attend to everything, especially every person (Zeifman, 2013).

sensation

The response of a sensory system (eyes, ears, skin, tongue, nose) when it detects a stimulus.

Sensation occurs when a sensory system detects a stimulus, as when the inner ear reverberates with sound or the eye’s retina and pupil intercept light. Thus, sensations begin when an outer organ (eye, ear, nose, tongue, or skin) meets anything that can be seen, heard, smelled, tasted, or touched.

perception

The mental processing of sensory information when the brain interprets a sensation.

Perception occurs when the brain processes a sensation. This happens in the cortex, usually as the result of a message from one of the sensing organs, such as from the eye to the visual cortex. The sight of a bottle, for instance, is conveyed from the retina to the optic nerve to the visual cortex, but it has no meaning unless the infant has been bottle-

Thus, perception follows sensation, when sensory stimuli are interpreted in the brain. Then cognition follows perception, when people think about what they have perceived. The baby might reach out for the bottle, you might examine the paper. The sequence from sensation to perception to cognition requires first that the sense organs function. No wonder the parts of the cortex dedicated to hearing, seeing, and so on develop rapidly. Now specifics.

HEARING The fetus hears during the last trimester of pregnancy; loud sounds trigger reflexes even without conscious perception. Familiar, rhythmic sounds such as a heartbeat are soothing: Sometimes newborns stop crying if they are held so an ear is on the mother’s chest.

Because of early maturation of the language areas of the cortex, even 4-

Infants become accustomed to the patterns of their native language, such as which syllable is stressed (various dialects differ), whether inflection matters (it is crucial in Chinese), whether certain sound combinations are repeated, and so on. All this is based on very careful listening, including of speech not directed toward them (Buttelmann et al., 2013).

Better are sounds directed to the infant. Thus, a newborn named Emily has no concept that Emily is her name, but she has the brain and auditory capacity to hear sounds in the usual speech range (not some sounds that other creatures can hear) and an inborn preference for repeated patterns and human speech.

By about 4 months, when her auditory cortex is rapidly creating dendrites, the repeated word Emily is perceived as well as sensed, especially because that sound emanates from interactions with the people she often sees, smells, and touches. Before 6 months, Emily opens her eyes and smiles when her name is called, perhaps babbling in response.

This rapid development of hearing is the reason newborn hearing is tested, and, if necessary, remediation begins in infancy. By age 5, those who got cochlear implants in the early months are much better at understanding and expressing language than those with identical losses but whose implants were added after age 2 (Tobey et al., 2013).

SEEING By contrast, vision is immature at birth. Although in mid-

Almost immediately, experience combines with maturation of the visual cortex to improve vision. Indeed, vision improves so rapidly that researchers are hard-

As perception builds, visual scanning improves. Thus, 3-

Because of this rapid development, babies should be allowed to see many sights. A crying baby might be distracted by being taken outside to watch passing cars. If possible, cataracts (present in about 1 newborn in 2,000) should be surgically removed in the early months (Medsinge & Nischal, 2015).

binocular vision

The ability to focus both eyes in a coordinated manner in order to see one image. Depth perception requires it.

Binocular vision (coordinating both eyes to see one image) cannot develop in the womb (nothing is far enough away), so many newborns use their two eyes independently, momentarily appearing wall-

THINK CRITICALLY: Which is more important in the first year of life, accurate hearing or seeing?

Depth perception (which requires binocular vision) is usually present by 3 months, but understanding depth takes experience. Not until toddlers have experienced crawling and walking do they know whether a surface is best traversed upright, sitting, or crawling (Kretch & Adolph, 2013). The senses and motor skills take time to coordinate.

TASTING AND SMELLING As with vision and hearing, smell and taste function at birth and rapidly adapt to the social world. Infants learn to appreciate what their mothers eat, first through breast milk and then through smells and spoonfuls of the family dinner.

The foods of a particular culture may aid survival: For example, bitter foods provide some defense against malaria, hot spices help preserve food and may prevent food poisoning, and so on (Krebs, 2009). Thus, for 1-

Notice once again how early experiences sculpt the brain. Taste preferences endure when a person migrates to another culture or when a particular food that was once protective is no longer so. Indeed, one reason for the obesity epidemic is that, when starvation was a threat, families sought high-

Adaptation also occurs for the sense of smell. When breast-

As babies learn to recognize each person’s scent, they prefer to sleep next to their caregivers, and they nuzzle into their caregivers’ chests—

TOUCH AND PAIN Similarly, the sense of touch is acute in infants. Wrapping, rubbing, massaging, and cradling are soothing. Even when their eyes are closed, some infants stop crying and visibly relax when held securely by their caregivers. In the first year of life, the heart rate slows and muscles relax when babies are stroked gently and rhythmically on the arm (Fairhurst et al., 2014).

In every culture, parents cuddle their newborns, rocking, carrying, and so on. Some touch (gentle of course) seems experience-

Indeed, in rural India, mothers need to be taught that the newborn’s need for warmth is more important than immediate bathing and massage, since both of those practices are common for infants and may, inadvertently, harm a newborn. Mothers are encouraged to wipe their newborns with a dry cloth and breast-

Pain, motion, and temperature are not among the traditional five senses, but they are often connected to touch. Some babies cry when being changed, distressed at the sudden coldness on their skin and by having to lie down, not held by their caregivers.

Scientists are not certain about pain. Some experiences that are painful to adults (circumcision, setting of a broken bone) are much less so to newborns, although that does not prove that newborns are unable to feel pain (Reavey et al., 2014).

Many young infants sometimes cry inconsolably; digestive pain is the usual explanation. Teething is also said to be painful. However, these explanations also are unproven. Certainly for adults, pain and crying do not always occur together.

For many newborn medical procedures, a taste of sugar right before the event is an anesthetic. One example is that newborns typically cry lustily when their heel is pricked (to get a blood sample, routine after birth), but when an experimental group had a drop of sucrose before the heel stick, they were much less likely to cry than babies in a control group who had no sucrose (Harrison et al., 2010).

THINK CRITICALLY: What political controversy makes objective research on newborn pain difficult?

Some people imagine that even the fetus feels pain; others say that pain receptors in the brain are not activated until months after birth. Physiological measures (stress hormones, erratic heartbeats, and brain waves) are studied to assess pain in preterm infants, who typically undergo many procedures that would be painful to an adult (Holsti et al., 2011). More research is needed.

Motor Skills

motor skills

The learned abilities to move some part of the body, in actions ranging from a large leap to a flicker of the eyelid. (The word motor here refers to movement of muscles.)

Every basic motor skill (any movement ability), from the newborn’s head-

REFLEXES The sequence of motor skills begins with reflexes, some of which are listed here in italics. Newborns have even more than the 17 on this list.

Reflexes that maintain oxygen supply. The breathing reflex begins even before the umbilical cord, with its supply of oxygen, is cut. Additional reflexes that maintain oxygen are reflexive hiccups and sneezes, as well as thrashing (moving the arms and legs about) to escape something that covers the face.

Reflexes that maintain constant body temperature. When infants are cold, they cry, shiver, and tuck their legs close to their bodies. When they are hot, they try to push away blankets and then stay still.

Reflexes that manage feeding. The sucking reflex causes newborns to suck anything that touches their lips—

fingers, toes, blankets, and rattles, as well as natural and artificial nipples of various textures and shapes. In the rooting reflex, babies turn their mouths toward anything that brushes against their cheeks— a reflexive search for a nipple— and start to suck. Swallowing also aids feeding, as does crying when the stomach is empty and spitting up when too much is swallowed quickly.

Other reflexes are not necessary for survival but signify the state of brain and body functions. Among them are the:

Babinski reflex. When a newborn’s feet are stroked, the toes fan upward.

Stepping reflex. When newborns are held upright, feet touching a flat surface, they move their legs as if to walk.

Swimming reflex. When held horizontally on their stomachs, newborns stretch out their arms and legs.

Palmar grasping reflex. When something touches the palms, newborns grip it tightly.

Moro reflex. When someone bangs on the table they are lying on, newborns fling their arms out and then bring them together on their chests, crying with wide-

open eyes.

Although the definition of reflexes implies that they are automatic, their strength and duration vary from one baby to another, and cultural responses shape them. Many newborn reflexes disappear by 3 months, but some morph into more advanced motor skills.

Reflexes become skills if they are practiced and encouraged. As you saw in the chapter’s beginning, Mrs. Todd set the foundation for my fourth child’s walking when Sarah was only a few months old. Similarly, some 1-

gross motor skills

Physical abilities involving large body movements, such as walking and jumping. (The word gross here means “big.”)

GROSS MOTOR SKILLS Deliberate actions that use many parts of the body, producing large movements, are called gross motor skills. These skills emerge directly from reflexes and proceed in a cephalocaudal (head-

Infants first control their heads, lifting them up to look around, an early example of cephalocaudal maturation. Then control moves downward—

Sitting develops gradually. By 3 months, most babies can sit propped up in a lap. By 6 months, they can usually sit unsupported. Babies never propped up (as in some institutions for abandoned infants) sit much later.

Question 3.1

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Which of these skills has the greatest variation in age of acquisition? Why?

Jumping up, with a three-

| When 50% of All Babies Master the Skill | When 90% of All Babies Master the Skill | |

|---|---|---|

| Sit unsupported | 6 | 7.5 |

| Stands holding on | 7.4 | 9.4 |

| Crawls (creeps) | 8 | 10 |

| Stands not holding | 10.8 | 13.4 |

| Walking well | 12.0 | 14.4 |

| Walk backward | 15 | 17 |

| Run | 18 | 20 |

| Jump up | 26 | 29 |

Note: As the text explains, age norms are affected by culture and cohort. The first five norms are based on babies on five continents [Brazil, Ghana, Norway, United States, Oman, and India] (World Health Organization, 2006). The next three are from a U.S. only source (Coovadia & Wittenberg, 2004; based on Denver II [Frankenburg et al., 1992]). Mastering skills a few weeks earlier or later does not indicate health or intelligence. Being very late, however, is a cause for concern.

Crawling is another example of the head-

Usually by 5 months, infants add their legs to this effort, inching forward (or backward) on their bellies. Exactly when this occurs depends partly on how much “tummy time” the infant has had to develop the muscles, and that, of course, is affected by the caregiver’s culture (Zachry & Kitzmann, 2011).

Most 8-

All babies find some way to move (inching, bear-

As soon as they are able, babies take some independent steps, falling frequently at first, about 32 times per hour. They persevere because walking is much quicker than crawling, and it has other advantages—

Once toddlers take those first unsteady steps, they practice obsessively, barefoot or not, at home or in stores, on sidewalks or streets, on lawns or in mud. They “immediately go more, see more, play more, and interact more” (Adolph & Tamis-

fine motor skills

Physical abilities involving small body movements, especially of the hands and fingers, such as drawing and picking up a coin. (The word fine here means “small.”)

FINE MOTOR SKILLS Small body movements are called fine motor skills. The most valued fine motor skills are finger movements, enabling humans to write, draw, type, tie, and so on. Movements of the tongue, jaw, lips, teeth, and toes are fine movements, too.

Actually, mouth skills precede hand skills by many months (newborns can suck; chewing precedes drawing by a year or more). Since every culture encourages finger dexterity, children practice finger movements, and adults teach how to use spoons, or chopsticks, or markers. By contrast, mouth skills such as spitting or biting are not praised. (Only other children admire blowing bubbles with gum.)

Video: Fine Motor Skills in Infancy and Toddlerhood

Regarding hand skills, newborns have a strong reflexive grasp but lack control. During their first 2 months, babies excitedly stare and wave their arms at objects dangling within reach. By 3 months, they can usually touch such objects, but because of limited eye–

By 4 months, infants sometimes grab, but their timing is off: They close their hands too early or too late. Finally by 6 months, with a concentrated, deliberate stare, most babies can reach, grab, and grasp almost any object that is of the right size. Some can even transfer an object from one hand to the other.

Almost all can hold a bottle, shake a rattle, and yank a sister’s braids. Toward the end of the first year and throughout the second, finger skills improve as babies master the pincer movement (using thumb and forefinger to pick up tiny objects) and self-

As with gross motor skills, fine motor skills are shaped by culture and opportunity. For example, when given “sticky mittens” (with Velcro) that facilitate grabbing, infants master hand skills sooner than the norm. Their perception advances as well (Libertus & Needham, 2010; Soska et al., 2010). As you remember, experience leads to perception and cognition.

COMBINING SENSES AND SKILLS All senses and motor skills expand the baby’s cognitive awareness, with practice advancing both skill and understanding (Leonard & Hill, 2014). In the second year, grasping becomes more selective, as experience sculpts the brain. Toddlers learn when not to pull at a sister’s braids or an adult’s earrings or glasses. (Wise adults, however, remove such accessories before holding a baby.)

| When 50% of All Babies Master the Skill | When 90% of All Babies Master the Skill | |

|---|---|---|

| Grasps rattle when placed in hand | 3 | 4 |

| Reaches to hold an object | 4.5 | 6 |

| Thumb and finger grasp | 8 | 10 |

| Stacks two blocks | 15 | 21 |

| Imitates vertical line (drawing) | 30 | 39 |

Data from World Health Organization, 2006.

The age at which walking occurs is a better predictor than simple chronological age of a child’s verbal ability, perhaps because walking children elicit more language from caregivers than crawling ones do (Walle & Campos, 2014). The correlation could go in the opposite direction as well: Walkers see their caregivers more, so they talk more (Adolph & Tamis-

Overall, babies perceive their most important experiences with several senses and skills, in dynamic systems. Breast milk, for instance, is a mild sedative, so the infant literally feels happier at the breast, connecting that pleasure with taste, touch, smell, and sight. But first, a motor skill is needed: The infant must actively suck at the nipple (an inborn reflex, which becomes more efficient with practice).

Because of brain immaturity, cross-

Remember the dynamic systems of senses and motor skills: If one aspect of the system lags behind, the other parts may be affected as well. On the other hand, young walkers are thrilled to grab dozens of objects they could not explore before—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 3.2

1. Why is it not a problem if an infant is consistently at the 20th percentile in height and weight?

Consistency is normal; inconsistency—

Question 3.3

2. How do sleep patterns change over the first 18 months?

Hours of sleep decrease rapidly with maturity: The norm per day for the first two months is 14 ¼ hours; for the next three months, 13 ¼ hours; and between six and 17 months of age, 12 ¾ hours.

Question 3.4

3. What are the reasons for and against co-

Some mothers, especially those in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, support co-

Question 3.5

4. How does the brain change from birth to age 2?

In the first two years of life, the brain grows more rapidly than any other organ, being about 25 percent of adult weight at birth and almost 75 percent at age two. Brain circumference during this time also increases from about 14 to 19 inches.

Question 3.6

5. How does communication occur within the central nervous system?

The cells of the central nervous system are called neurons. Each neuron has a single axon and numerous dendrites, which spread out like the branches of a tree, making connections with the dendrites and axons of other neurons. Neurons communicate by sending electrochemical impulses through their axons to synapses to be picked up by the dendrites of other neurons.

Question 3.7

6. How can pruning increase brain potential?

Pruning is important for the initial organization of the brain; it also increases brainpower.

Question 3.8

7. What is the difference between experience-

Brain development is experience-

Question 3.9

8. What should caregivers remember about brain development when an infant cries?

Infants cry as a reflex to pain, but they are too immature to decide to stop crying.

Question 3.10

9. How does an infant’s vision change over the first year?

Vision improves so rapidly in the first year that researchers find it difficult to describe the day-

Question 3.11

10. How do infants’ senses strengthen their early social interactions?

Newborns and young babies’ strongest sense is hearing. Familiar, rhythmic sounds such as a heartbeat help soothe them, and the sounds of their caregivers’ voices get them accustomed to their native language. Infants’ rapidly improving vision means that they can be distracted by interesting sights when fussy and can offer social smiles to their caregivers by about 2 months. Taste and smell help them appreciate the smells and foods of their culture, first through breast milk and later through bites of the family dinner. Their sense of touch can help them relax through cradling, massage, rocking, etc.

Question 3.12

11. In what two directions do infants’ gross motor skills emerge?

Gross motor skills proceed in a cephalocaudal (head-

Question 3.13

12. Which fine motor skills are developed in infancy?

Newborns have a strong reflexive grasp but lack control. By 3 months, infants can touch objects dangling within reach. By 4 months, infants can sometimes grab, though their timing is often off. By 6 months, however, most babies can reach, grab, and grasp almost any object that is the proper size. Toward the end of the first year, finger skills improve as babies master the pincer grip.