Surviving in Good Health

Although precise worldwide statistics are unavailable, the United Nations estimates that more than 8 billion children were born between 1950 and 2015 and that almost a billion of them died before age 5. Far more would have died without recent public health measures.

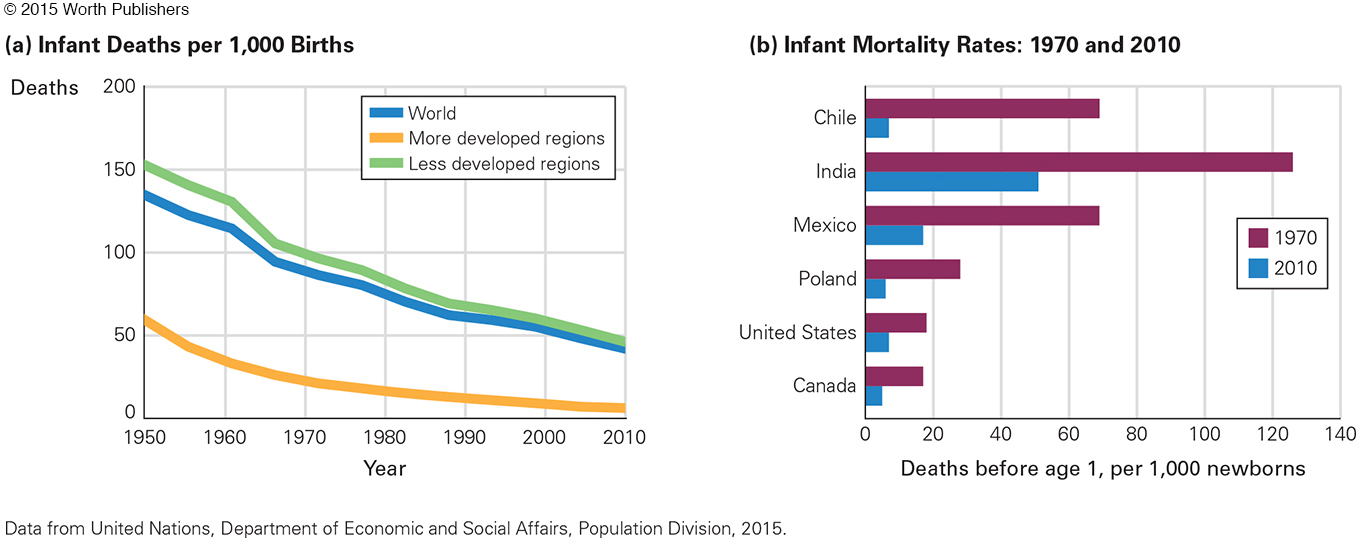

In 1950, one young child in five died, but only about one child in twenty died in 2015 (United Nations, 2015). Infant death was worse in earlier centuries, when more than half of all children died in infancy. Those are official statistics; probably millions more died without being counted.

Better Days Ahead

Now almost all newborns who survive the first month live to adulthood. Some nations have seen dramatic improvement. Chile’s rate of infant mortality, for instance, was almost four times higher than the rate in the United States in 1970; now both nations have improved and their rates are the same (see Figure 3.5).

As more children survive, parents focus more effort and income on each child, having fewer children overall. That advances the national economy, which allows for better schools and health care.

Infant survival and maternal education are the two main reasons the world’s fertility rate in 2010 was half the 1950 rate. This is found in data from numerous nations, especially developing ones, where educated women have far fewer children than those who are uneducated (de la Croix, 2013).

Educated women also have healthier children, in part because they are more aware of research that emphasizes breast-

In an example reported on the front page of newspapers in the United States and Denmark, a Danish woman, Annette Sorenson, left her 14-

Sorenson was arrested for child neglect, her daughter placed in foster care briefly until a judge ordered her returned (Marcano, 1997). The mother sued the city for harming her as well as her child, who was unhurt. The lawsuit was dismissed, but it is obvious that cultures have contrasting assumptions regarding infant care.

Remember, difference is not deficit. Usually variations are simply alternative ways to meet basic infant needs. However, not every cultural practice is equally good. Each practice needs to be considered carefully, especially when cultures differ.

sudden infant death (SIDS)

An infant’s unexpected, sudden death; when a seemingly healthy baby, usually between 2 and 6 months old, stops breathing and dies while asleep.

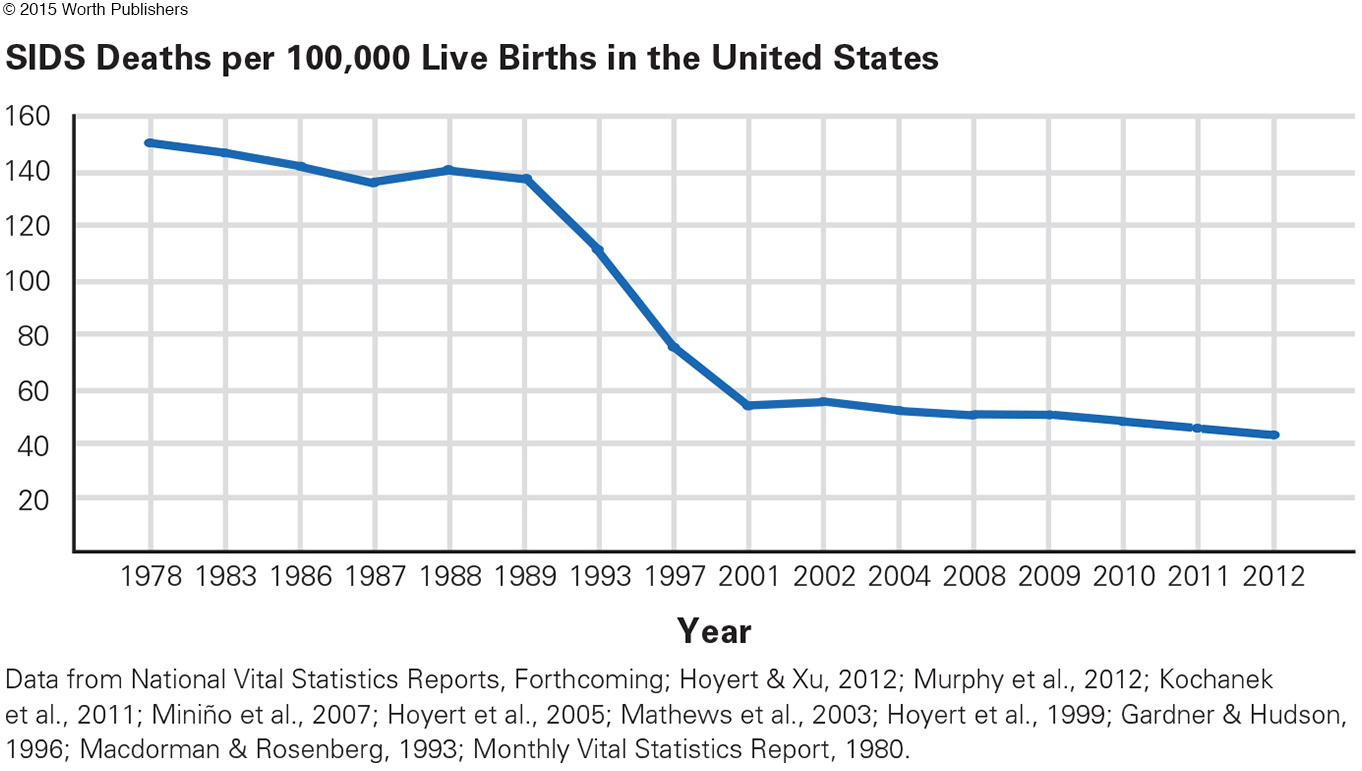

For example, every year until the mid-

As parents mourned, scientists asked why, testing hypotheses (the cat? the quilt? natural honey? homicide? spoiled milk?) to no avail. Sudden infant death was a mystery. To some extent, it still is, but one risk factor—

A CASE TO STUDY

Scientist at Work

Susan Beal, a young Australian scientist with four children, studied SIDS. Often she was phoned at dawn, to be told that another baby had died. She drove to the house, sometimes arriving before the police, finding parents who were grateful that someone was trying to discover what had just killed their child.

Parents tended to blame themselves and each other; Beal reassured them that it was not their fault and that scientists shared their bewilderment. Rates were known to be lower in breast-

Beal’s detailed notes on dozens of SIDS deaths revealed what didn’t matter (birth order) and what did (parental cigarette smoking). She noticed a surprising ethnic variation: Although a sizable minority of Australians are of Chinese descent, their babies almost never died of SIDS. Most experts thought this was genetic, but Beal noted something else. Almost all SIDS babies died when they were sleeping on their stomachs, contrary to the Chinese custom of placing infants on their backs to sleep.

Beal convinced a large group of non-

Beal’s published report in the Medical Journal of Australia (Beal, 1988) caught the attention of doctors in the Netherlands. Two Dutch scientists (Engelberts & de Jonge, 1990) recommended back-

Australian Women: Shaping a Nation

Worldwide, putting babies “Back to Sleep” has now cut the SIDS rate dramatically (Mitchell & Krous, 2015). In 1984 SIDS killed 5,245 babies in the United States; in 1996, 3,050; in 2010, about 1,700 (see Figure 3.6). In the United States alone, 100,000 children and young adults are alive today who would be dead if they had been born before 1990.

Stomach-

Immunization

immunization

A process that stimulates the body’s immune system to defend against attack by a particular contagious disease. Immunization may be accomplished either naturally (by having the disease) or through vaccination (often by having an injection). (Also called vaccination.)

Immunization primes the body’s immune system to resist a particular disease. Within the past 50 years, immunization eliminated smallpox and dramatically reduced chicken pox, flu, measles, mumps, pneumonia, polio, rotavirus, tetanus, and whooping cough. Now scientists seek to immunize against HIV/AIDS, malaria, Ebola, and other viral diseases.

Stunning successes include the following:

Smallpox, the most lethal disease for children in the past, was eradicated worldwide as of 1980. Vaccination against smallpox is no longer needed.

Polio, a crippling and sometimes fatal disease, is rare. Widespread vaccination, begun in 1955, eliminated polio in the Americas. Currently, the only nation where polio is endemic is Pakistan, where violence prevents public health workers from reaching many children.

Measles is disappearing, thanks to a vaccine developed in 1963. Prior to that time, 3 to 4 million cases occurred each year in the United States alone (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, April, 2015). In the United States the lowest year on record was 2012, when only 55 people had measles, most of them born in nations without widespread immunization (MMWR, January 2, 2015).

Immunization protects not only from temporary sickness but also from complications, including deafness, blindness, sterility, and meningitis. Sometimes the damage from illness is not apparent until years later. Having mumps in childhood, for instance, can cause male sterility and doubles the risk of schizophrenia in adulthood (Dalman et al., 2008). Measles weakens the immune system, making later death more likely (Mina et al., 2015).

PROBLEMS WITH IMMUNIZATION Immunization is not safe for newborns or people with impaired immune systems (HIV-

Some parents refuse to vaccinate their children for medical reasons; every state in the United States allows such exemptions. However, in 19 states, parents can refuse vaccination because of “personal belief” (Blad, 2014). In Colorado, for instance, 15 percent of all kindergartners have never been immunized against measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, tetanus, or whooping cough. That is below herd immunity, and an epidemic could occur—

Globally, about 20 million cases of measles occur each year, almost all in nations with inadequate public health. If a traveler brings measles back to the United States, unimmunized children and adults may catch the disease. That happened in 2014, when the number of U.S. measles cases was 554, ten times the rate only two years before (MMWR, January 2, 2015).

Infants may react to immunization by being irritable or even feverish for a day or so, to the distress of their parents. However, parents do not notice if their child does not get polio, measles, or so on. Before the varicella (chicken pox) vaccine, more than 100 people in the United States died each year from that disease, and 1 million were itchy and feverish for a week. Now almost no one dies of varicella, and only a few get chicken pox.

Many parents worry about the possible side effects of vaccines. This horrifies public health workers, who, taking a longitudinal and society-

As you will see later, the fear that infant immunization leads to autism is unfounded; children who are not immunized are no less likely to have an autism spectrum disorder, but much more likely to become sick. It is easy to understand why parents of such a child would seek to blame something other than genes or teratogens, but in this case a cultural fear is destructive.

Nutrition

As already explained, infant mortality worldwide has plummeted for several reasons: fewer sudden infant deaths, advances in prenatal and newborn care, clean water, and, as you just read, immunization. One more measure is making a huge difference: better nutrition.

Video: Nutritional Needs of Infants and Children: Breast-

BREAST MILK The World Health Organization now recommends exclusive breast-

Breast-

The more research is done, the better breast milk seems. For instance, the composition of breast milk adjusts to the age of the baby, with milk for premature babies distinct from that for older infants. Quantity increases to meet the demand: Twins and even triplets can be exclusively breast-

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

From Breast to Formula and Back

Scientific discovery does not always proceed smoothly in one direction. Research on breast milk shows that. Four generations of women in my family heeded the best evidence known at the time when we fed our children.

A hundred years ago, my grandmother, an immigrant who spoke accented English, breast-

Two of Grandma’s babies died in infancy. Did insufficient nutrition play a role?

By the middle of the twentieth century, scientists had analyzed breast milk and created formula, designed to be far better than cow’s milk. Formula solves the problems of breast-

That is why my mother formula-

Companies that sold formula promoted it in Africa and Latin America as well as North America. They paid local women in developing nations to convince mothers to buy formula.

Then public health workers compiled statistics on infant mortality: In developing nations formula-

In sympathy for those dying babies, I was among the thousands of North Americans who boycotted products from the offending manufacturers. I breast-

Longitudinal research continues. The data led to a new conclusion: Even with good sterilization, in every nation breast-

|

For the Baby Balance of nutrition (fat, protein, etc.) adjusts to age of baby Breast milk has micronutrients not found in formula Less infant illness, including allergies, ear infections, stomach upsets Less childhood asthma Better childhood vision Less adult illness, including diabetes, cancer, heart disease Protection against many childhood diseases, since breast milk contains antibodies from the mother Stronger jaws, fewer cavities, advanced breathing reflexes (less SIDS) Higher IQ, less likely to drop out of school, more likely to attend college Later puberty, fewer teenage pregnancies Less likely to become obese or hypertensive by age 12 For the Mother Easier bonding with baby Reduced risk of breast cancer and osteoporosis Natural contraception (with exclusive breast- Pleasure of breast stimulation Satisfaction of meeting infant’s basic need No formula to prepare; no sterilization Easier travel with the baby For the Family Increased survival of other children (because of spacing of births) Increased family income (because formula and medical care are expensive) Less stress on father, especially at night |

International research continues. In Africa, an infant’s risk of catching HIV from a breast-

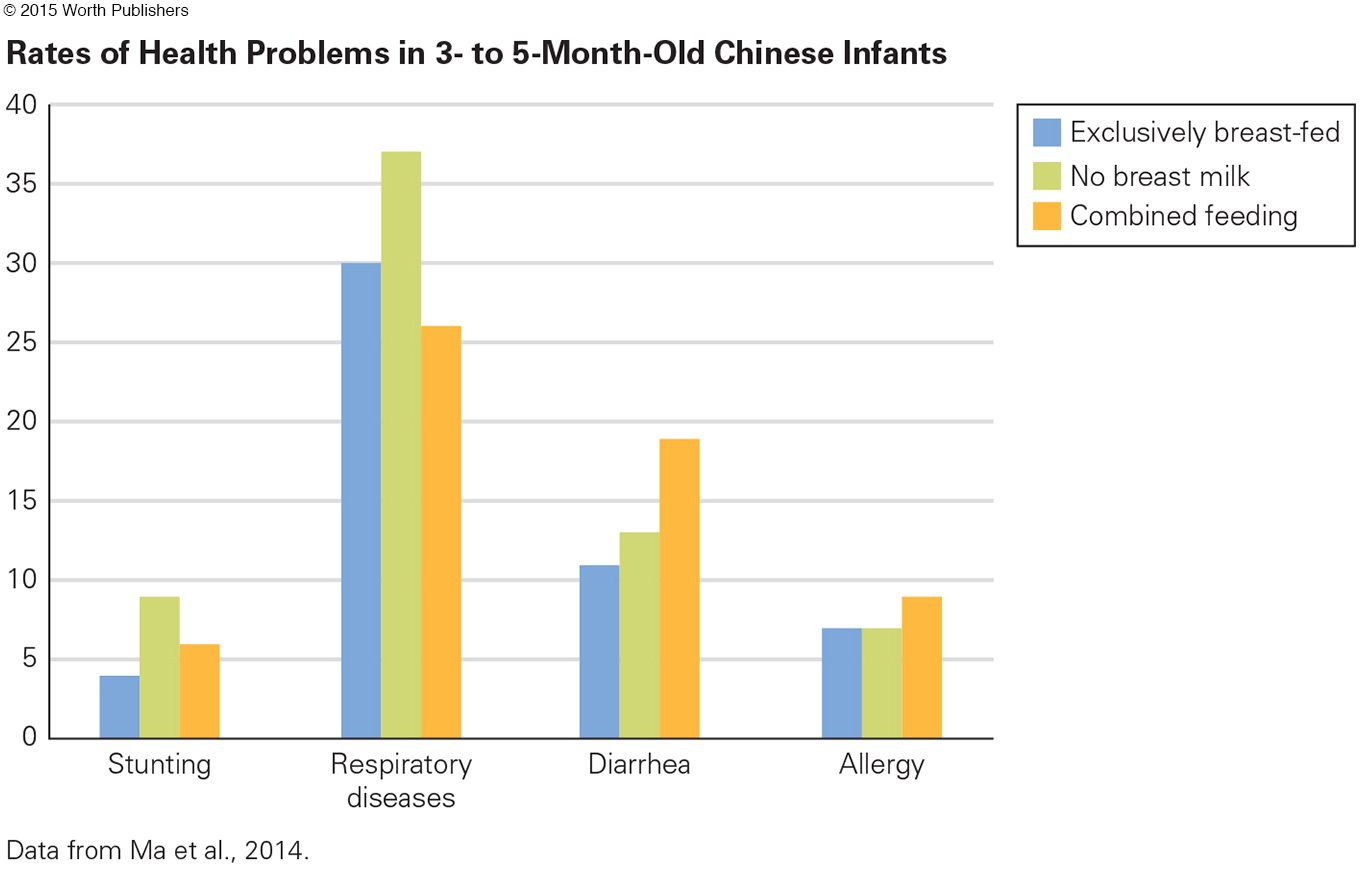

In China, a study of more than a thousand babies in eight cities compared three groups of babies: those exclusively breast-

Question 3.14

OBSERVATION QUIZ

In what one way might exclusive breast-

Combination feeding might provide some protection against the common cold. The advantage is not much (a difference of 5 percent) and may be because exclusively breast-

The research has caused a dramatic cohort change in the United States. Currently most (about 80 percent) mothers breast-

Virtually all scientists and pediatricians have reached a conclusion opposite to the one their predecessors held 50 years ago: Infants should be nourished only by breast milk until they are 4 to 6 months old.

THINK CRITICALLY: For new mothers in your community, why do some use formula and others breast-

As of 2015 about 200 hospitals in the United States and hundreds more worldwide have been designated as “Baby-

Our knowledge advances with each generation. I wonder what the future will bring when my grandchildren become parents.

protein-

A condition in which a person does not consume sufficient food of any kind. This deprivation can result in illness, severe weight loss, and even death.

stunting

The failure of children to grow to a normal height for their age due to severe and chronic malnutrition.

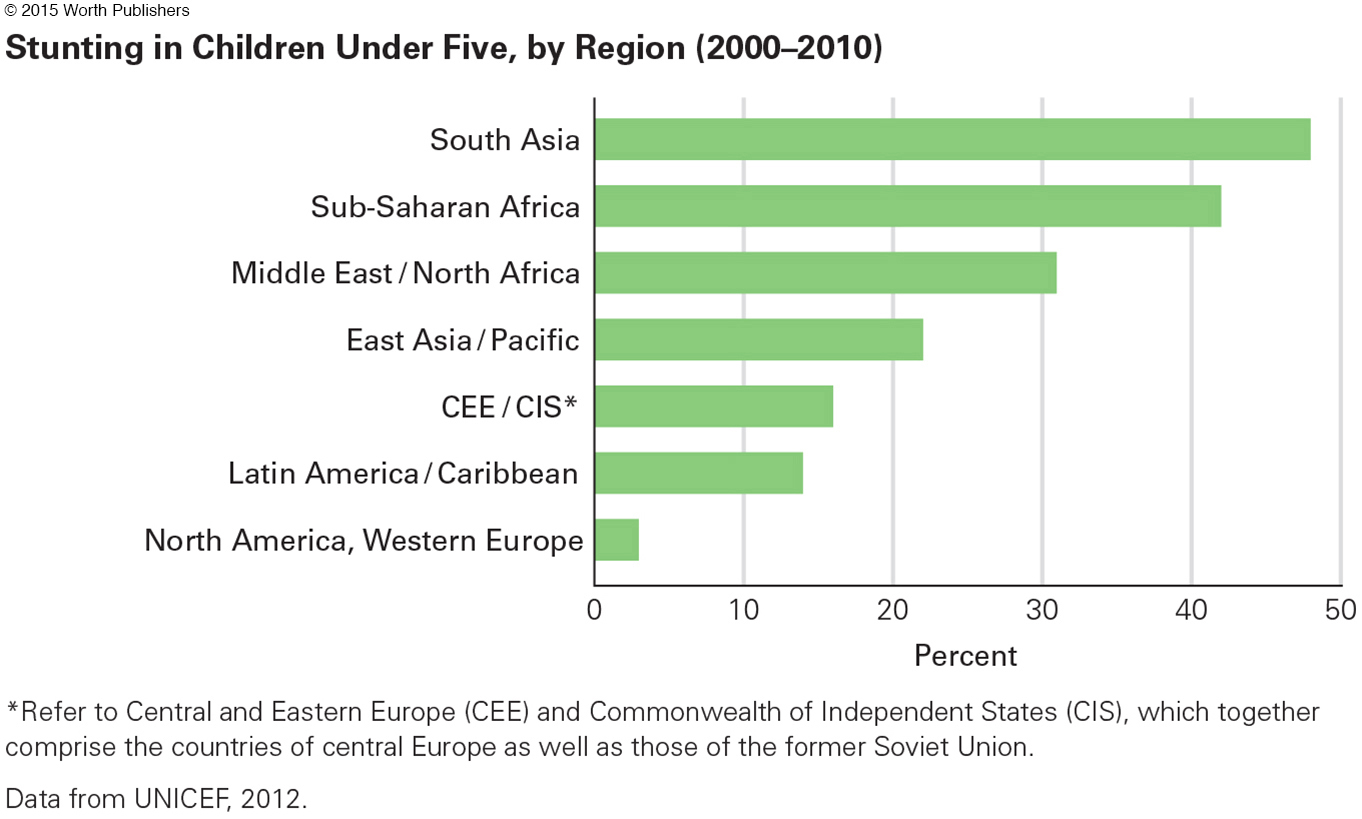

MALNUTRITION Protein-

wasting

The tendency for children to be severely underweight for their age as a result of malnutrition.

Even worse is wasting, when children are severely underweight for their age and height (2 or more standard deviations below average). Many nations, especially in East Asia, Latin America, and central Europe, have seen improvement in child nutrition in the past decades, with an accompanying decrease in wasting and stunting.

In other nations, however, primarily in Africa, wasting has increased. And in several nations in South Asia, about one-

Some of this is directly related to brain growth, but in addition, the severely malnourished infant has less energy and reduced curiosity. Young children naturally want to do whatever they can: A child with no energy is a child who is not learning.

An added problem is disease. Malnourished children have no body reserves to protect them against common diseases. A decade ago, scientists reported in the leading medical journal in England that half of all childhood deaths occur because malnutrition makes a childhood disease lethal (Black et al., 2003).

Video: Malnutrition and Children in Nepal shows the plight of children in Nepal who suffer from protein calorie malnutrition.

marasmus

A disease of severe protein-

kwashiorkor

A disease of chronic malnutrition during childhood, in which a protein-

Finally, some diseases result directly from malnutrition—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 3.15

1. Why do public health doctors wish that all infants worldwide would get immunized?

Immunization primes the body’s immune system to resist a particular disease. Within the past 50 years, immunization eliminated smallpox and dramatically reduced chicken pox, flu, measles, mumps, pneumonia, polio, rotavirus, tetanus, and whooping cough. Now, scientists seek to immunize against HIV/AIDS, malaria, Ebola, and other viral diseases.

Question 3.16

2. Why would a parent blame immunization for autism spectrum disorder?

Parents of children with autism spectrum disorder may be angry or confused about how their child developed ASD. They may seek to blame something other than genes or teratogens, but the fear that infant immunization leads to ASD is unfounded. Children who are not immunized are no less likely to have autism spectrum disorder but are much more likely to become sick.

Question 3.17

3. What is herd immunity?

When children are vaccinated and stop transmission of a disease, thus protecting others who are vulnerable, a phenomenon called herd immunity occurs. Public health doctors worry when too many parents avoid immunization, because herd immunity decreases as a result.

Question 3.18

4. What are the reasons for exclusive breast-

In infancy, breast milk provides antibodies against any disease to which the mother is immune and decreases allergies and asthma. Babies who are exclusively breast-

Question 3.19

5. What is the relationship between malnutrition and disease?

Malnourished children have no body reserves to protect them against common diseases.

Question 3.20

6. What diseases are caused directly by malnutrition?

During the first year, malnutrition can cause marasmus, which causes body tissues to waste away. After age 1, kwashiorkor can occur; with this disease, growth slows down, hair becomes thin, skin becomes splotchy, and the face, legs, and abdomen swell with fluid (edema).

Question 3.21

7. What is the difference between stunting and wasting?

Stunting is failure of children to grow to a normal height for their age due to severe and chronic malnutrition. Wasting happens when children are severely underweight for their age as a result of malnutrition.

Question 3.22

8. In what ways does malnutrition affect cognition?

Adults who suffered from wasting in their first year of life have lower IQs throughout life, even if they are well fed after infancy. Some of this is directly related to brain growth. In addition, a severely malnourished infant has less energy and reduced curiosity and therefore is not learning.