Emotional Development

In their first two years, infants progress from reactive pain and pleasure to complex patterns of social awareness (see At About This Time), a movement from reflexive emotions to learned and then thoughtful ones (Panksepp & Watt, 2011). Infant emotions arise more from basic impulses than from the cortex, so speedy, uncensored reactions—

130

| Birth | Distress; contentment |

| 6 weeks | Social smile |

| 3 months | Laughter; curiosity |

| 4 months | Full, responsive smiles |

| 4– |

Anger |

| 9– |

Fear of social events (strangers, separation from caregiver) |

| 12 months | Fear of unexpected sights and sounds |

| 18 months | Self- |

As always, culture and experience influence the norms of development. This is especially true for emotional development after the first eight months.

Early Emotions

At first there is pleasure and pain. Both are evident throughout infancy, even throughout life, but the triggers, reasons, and expressions change with development, and many new emotions appear.

AT BIRTH Newborns are happy and relaxed when fed and drifting off to sleep. They cry when they are hurt or hungry, tired or frightened (as by a loud noise or a sudden loss of support). Some infants have bouts of uncontrollable crying, called colic, probably the result of immature digestion; some have reflux, probably the result of immature swallowing. About 20 percent of babies cry “excessively,” defined as more than three hours a day, more than three days a week, more than three weeks (J. S. Kim, 2011).

Curiosity is also present, although briefly, as sleep and hunger overtake almost every other reaction. Even a crying baby can suddenly grow quiet, when sucking and food overcome the emotion.

social smile

A smile evoked by a human face, normally first evident in full-

SMILING AND LAUGHING Soon, additional emotions become recognizable. Happiness is expressed by the social smile, evoked by a human face at about 6 weeks for full-

Infants worldwide express social joy, even laughter, between 2 and 4 months (Konner, 2007; Lewis, 2010). Laughter builds as curiosity does; a typical 6-

ANGER AND SADNESS The positive emotions of joy and contentment are joined by negative emotions. Obvious anger appears by 6 months, usually triggered by frustration, such as when infants are prevented from moving or grabbing. Infants hate to be strapped in, caged in, closed in, or even just held in place when they want to explore.

In infancy, anger is generally a healthy response to frustration, unlike sadness, which also appears in the first months. Sadness indicates withdrawal and is accompanied by a greater increase in the body’s production of cortisol.

Since sadness produces physiological stress (measured by cortisol levels), sorrow negatively impacts the infant. All social emotions, particularly sadness and fear, probably shape the brain (Fries & Pollak, 2007; Johnson, 2011). As you learned in Chapter 3, experience matters. Sad and angry infants whose mothers are depressed become fearful toddlers (Dix & Yan, 2014). Too much sadness early in life correlates with depression later on.

FEAR Fear in response to some person, thing, or situation (not just being startled in surprise) is evident at about 9 months and soon becomes more frequent and obvious. Two kinds of social fear are typical:

separation anxiety

An infant’s distress when a familiar caregiver leaves; most obvious between 9 and 14 months.

stranger wariness

An infant’s expression of concern—

Separation anxiety—clinging and crying when a familiar caregiver is about to leave

Stranger wariness—fear of unfamiliar people, especially when they move too close, too quickly

131

Separation anxiety is normal at age 1, intensifies by age 2, and usually subsides after that. Fear of separation interferes with infant sleep. For example, infants who fall asleep next to familiar people may wake up frightened if they are alone (Sadeh et al., 2010). The solution is not necessarily to sleep with the baby, but neither is it to ignore the child’s natural fear of separation.

Some babies are comforted by a “transitional object,” such as a teddy bear or blanket, beside them as they transition from sleeping in their parents’ arms to sleeping alone. Music, a night light, or an open door may ease the fear.

Transitional objects are not pathological; they are the infant’s way of coping with anxiety. However, if separation anxiety remains strong after age 3 and impairs the child’s ability to leave home, go to school, or play with friends, it is considered an emotional disorder. Separation anxiety as a disorder can be diagnosed up to age 18 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); some clinicians diagnose it in adults as well (Bögels et al., 2013).

Separation anxiety may be apparent outside the home. Strangers—

Many normal 1-

Toddlers’ Emotions

Emotions take on new strength during toddlerhood, as both memory and mobility advance (Izard, 2009). For example, throughout the second year and beyond, anger and fear become less frequent but more focused, targeted toward infuriating or terrifying experiences. Similarly, laughing and crying are louder and more discriminating. This is the familiar path from sensation to perception to cognition.

The new strength of emotions is apparent in temper tantrums. Toddlers are famous for fury. When something angers them, they might yell, scream, cry, hit, and throw themselves on the floor. Logic is beyond them; if adults respond with anger or teasing, that makes it worse.

One child was angry at her feet and said she did not want them. When a parent offered to get a scissors and cut them off, a new wail of tantrum erupted. With temper tantrums, soon sadness comes to the fore, at which time comfort—

THINK CRITICALLY: Which is more annoying, people who brag or people who call themselves “stupid”?

SOCIAL AWARENESS Temper can be seen as an expression of selfhood. So can new toddler emotions: pride, shame, jealousy, embarrassment, disgust, and guilt. These emotions require social awareness, which typically emerges from family interactions. For instance, in a study of infant jealousy, when mothers deliberately paid attention to another infant, babies moved closer to their mothers, bidding for attention. Brain activity also registered social awareness (Mize et al., 2014).

Culture is crucial here, with independence a value in some families but not in others. Many North American parents encourage toddler pride (saying, “You did it yourself”—even when that is untrue), but Asian families typically cultivate modesty and shame. Such differences may still be apparent in adult personality and judgment.

132

Disgust is also strongly influenced by other people. According to a study that involved children of various ages, many 18-

self-

A person’s realization that he or she is a distinct individual whose body, mind, and actions are separate from those of other people.

SELF-

In a classic experiment (Lewis & Brooks, 1978), 9-

However, at some time between 15 and 24 months, babies become self-

As another scholar explains it, “an explicit and hence reflective conception of the self is apparent at the early stage of language acquisition at around the same age that infants begin to recognize themselves in mirrors” (Rochat, 2013, p. 388). This is yet another example of the interplay of all the infant abilities—

Brain and Emotions

Brain maturation is involved in the developments just described because every reaction begins in the brain (Johnson, 2011). Experience produces connections between neurons and emotions.

Links between expressed emotions and brain growth are complex and thus difficult to assess and describe with precision (Lewis, 2010). Compared with the emotions of adults, discrete emotions—

The growth of synapses and dendrites is a likely explanation for the gradual refinement and expression of each emotion, the result of past experiences and ongoing maturation. Already by 6 months, an infant’s brain patterns and stress hormones seem affected by caregiver responsiveness (Enlow et al., 2014).

Video Activity: Self-Awareness and the Rouge Test shows the famous assessment of how and when self-

GROWTH OF THE BRAIN Many specific aspects of brain development support social emotions (Lloyd-

Cultural differences become encoded in the infant brain, called “a cultural sponge” by one group of scientists (Ambady & Bharucha, 2009, p. 342). It is difficult to measure exactly how infant brains are molded by their context, in part because few parents give permission for scanning the brains of their normally developing infants. However, in one study (Zhu et al., 2007) adults—

133

Researchers consider this finding to be “neuroimaging evidence that culture shapes the functional anatomy of self-

Beyond culture, an infant’s brain activity interacts with caregiver responses, probably in the first months of life as well as through the years of childhood (E. Nelson et al., 2014). Highly reactive 15-

By age 4, they could regulate their emotions, no longer bursting into tears at any distress. Presumably they had developed neurological links between brain excitement and emotional response, so their excitement was connected to thought. However, highly reactive toddlers whose caregivers were less responsive were often overwhelmed by their emotions later on (Ursache et al., 2013). Differential susceptibility is apparent: Innate reactions and caregiver actions together sculpt the brain.

LEARNING ABOUT OTHERS The tentative social smiles of 2-

Social preferences form in the early months, connected not only with a person’s face but also with voice, touch, and smell. Early social awareness is one reason adopted children ideally join their new parents in the first days of life (a marked change from 100 years ago, when adoptions began after age 1).

Social awareness is also a reason to respect an infant’s reaction to a babysitter: If a 6-

Every experience that a person has—

As illustrated in Visualizing Development in Chapter 3, p. 95, this was first shown dramatically with baby mice: Some were licked and nuzzled by their mothers almost constantly, and some were neglected. A mother mouse’s licking of her newborn babies reduced methylation of a gene (Nr3c1), which allowed more serotonin (a neurotransmitter) to be released by the hypothalamus (a region of the brain discussed in Chapter 5).

Serotonin not only increased momentary pleasure (mice love being licked) but also started a chain of epigenetic responses to reduce cortisol from many parts of the brain and body, including the adrenal glands. The effects on both brain and behavior are lifelong for mice and probably for humans as well.

For many humans, social anxiety is stronger than any other anxiety. Certainly to some extent this is genetic. But epigenetic research finds environmental influences are important as well. This was clearly shown in a longitudinal study of 1,300 adolescents (twins and siblings): Their genetic tendency toward anxiety was evident at every age, but life events affected how strong that anxiety was felt (Zavos et al., 2012).

A smaller study likewise found that if the infant of an anxious biological mother is raised by a responsive adoptive mother who is not anxious, the inherited anxiety does not materialize (Natsuaki et al., 2013).

134

Parents need to be comforting (as with the nuzzled baby mice) but not overprotective. Fearful mothers tend to raise fearful children, but fathers who offer their infants exciting but not dangerous challenges (such as a game of chase, crawling on the floor) reduce later anxiety (Majdandži´c et al., 2013).

STRESS Emotions are connected to brain activity and hormones; they are affected by genes, past experiences, and additional hormones and neurotransmitters. Many of the specifics are not yet understood, but one link is clear: Excessive fear and stress harms the developing brain.

The specific mechanism seems to be that normally “the mother’s presence acts as a social buffer,” keeping cortisol levels low and thus fear at bay. However, if that does not occur, the brain develops more rapidly than normal. In that case, a child who seems adultlike in some emotions later becomes impaired because the parts of the brain that respond to emotions developed too quickly (Tottenham, 2014).

Brain scans of children who were maltreated in infancy show abnormal responses to stress, anger, and other emotions later on, including to photographs of frightened people. Some children seem resilient, but many areas of the brain (the prefrontal cortex, discussed in Chapter 3, and the hypothalamus, amygdala, HPA axis, and hippocampus, which will be explained in later chapters) are affected by abuse, especially if the maltreatment begins before age 2 (Bernard et al., 2014; Cicchetti, 2013a).

Since early caregiving affects the brain lifelong, caregivers should be consistent and reassuring. This is not always easy. Remember that some infants cry inconsolably in the early weeks. One researcher notes:

An infant’s crying has 2 possible consequences: it may elicit tenderness and desire to soothe, or helplessness and rage. It can be a signal that encourages attachment or one that jeopardizes the early relationship by triggering depression and, in some cases, even neglect or abuse.

[J. S. Kim, 2011, p. 229]

Sometimes mothers are blamed, or blame themselves, when an infant cries. This attitude is not helpful: A mother who feels guilty or incompetent may become angry at her baby, which leads to unresponsive parenting, an unhappy child, and then hostile interactions. (Presumably the results would be the same if the father, or grandmother, were the primary caregiver, although extensive research on those infant–

But the opposite may occur if early crying produces solicitous parenting. Then, when the baby outgrows the crying, the parent–

A study of colicky babies found both reactions in the parents (Landgren et al., 2012). One mother said:

There were moments when, both me and my husband … when she was apoplectic and howling so much that I almost got this thought, ‘now I’ll take a pillow and put over her face just until she quietens down, until the screaming stops.’

By contrast, another mother said

In some way, it made me stronger, and made my relationship with my son stronger … Because I felt that he had no one else but me. ‘If I can´t manage, no one can.’ So I had to cope.

Remember from Chapter 3 that cross-

135

The tendency of one part of the brain to activate another may also occur for emotions. An infant’s cry can be triggered by pain, fear, tiredness, surprise, or excitement; laughter can turn to tears. Infant emotions may erupt, increase, or disappear for unknown reasons (Camras & Shutter, 2010). Brain immaturity is a likely explanation.

Temperament

Video: Temperament in Infancy and Toddlerhood

temperament

Inborn differences between one person and another in emotions, activity, and self-

Temperament is defined as the “biologically based core of individual differences in style of approach and response to the environment that is stable across time and situations” (van den Akker et al., 2010, p. 485). “Biologically based” means that these traits originate with nature, not nurture. Confirmation that temperament arises from the inborn brain comes from an analysis of the tone, duration, and intensity of infant cries after the first inoculation, before much experience outside the womb. Cry variations at this very early stage correlate with later temperament (Jong et al., 2010).

Temperament is not the same as personality, although temperamental inclinations may lead to personality differences. Generally, personality traits (e.g., honesty and humility) are learned, whereas temperamental traits (e.g., shyness and aggression) are genetic. Of course, for every trait, nature and nurture interact.

In laboratory studies of temperament, infants are exposed to events that are frightening or attractive. Four-

Generally, three dimensions of temperament are found (Hirvonen et al., 2013; van den Akker et al., 2010; Degnan et al., 2011), each of which affects later personality and achievement.

Effortful control (regulating attention and emotion, self-

soothing) Negative mood (fearful, angry, unhappy)

Exuberant (active, social, not shy)

Each of these dimensions is associated with distinctive brain patterns as well as behavior, with the last of these (exuberance versus shyness) most strongly traced to genes (Wolfe et al., 2014). Of course, all temperament traits are thought to be biologically based with a genetic component, but the distinction between temperament (biology) and personality (learned) is clearer on paper than in people. Social scientists sometimes interpret the data in opposite ways, as you will now see.

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Mothers or Genes?

Traditionally, as you will later read, psychologists emphasized mothers. Their actions in the early years were thought to affect their child lifelong. Many adults credit, or blame, their mothers for their success and failure.

Recently, however, genetic research and neuroscience suggest a strong role for genes and neurotransmitters, making one person fearful and another foolhardy, one person angry and another sanguine, and so on. These studies often include photos of brain scans, and statistical analysis of monozygotic twins, leading many social scientists to be impressed by the biological basis for human differences.

Many neuroscientists seek to discover which alleles affect specific emotions. For example, researchers have found that the 7-

136

Many other scientists trace the traits of children to aspects of early caregiving and culture. For example, the same study that noted a link between MOA and infant anger compared Dutch and American babies, and it reported that culture was a crucial influence (Sung et al., 2015). The impact of the 7-

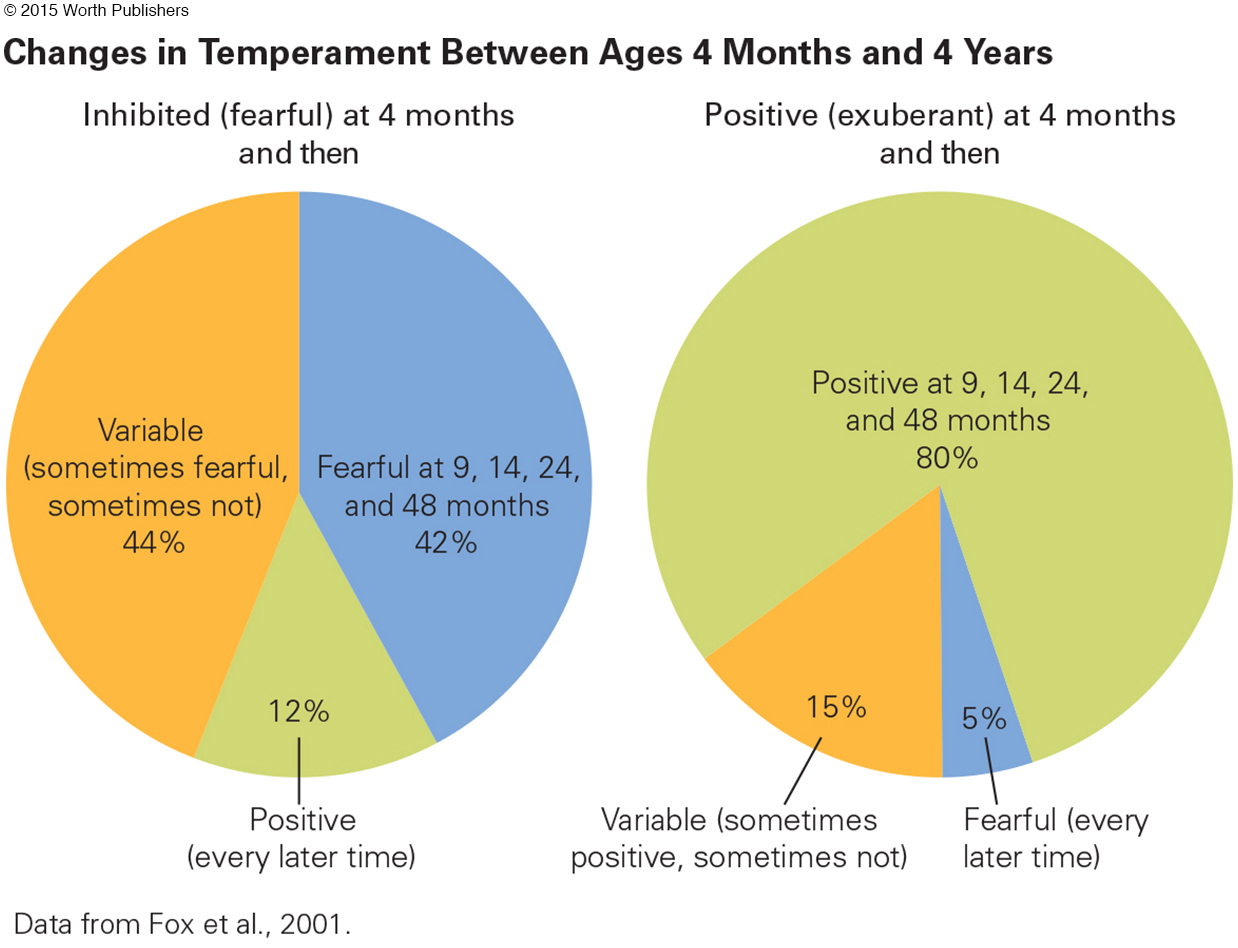

The most detailed, longitudinal study of temperament assessed the same individuals at 4, 9, 14, 24, and 48 months and again in middle childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. The scientists designed laboratory experiments with specifics appropriate for the age of the children; collected detailed reports from the mothers and later from the participants themselves; and gathered observational data and physiological evidence, including brain scans. Past data were reevaluated each time, and cross-

Half of the participants did not change much over time, reacting the same way and having similar brain-

The researchers found unexpected gender differences. As teenagers, the formerly inhibited boys were more likely than the average adolescent to use drugs, but the inhibited girls were less likely to do so (L. Williams et al., 2010). Perhaps shy boys use drugs to become less anxious, but shy girls may be more fearful of authority and more accepted as they are. Is this nature (sex hormones) or nurture (social expectations)?

Examination of these participants in adulthood again found intriguing differences between brain and behavior. Those who were inhibited in childhood still showed, in brain scans, evidence of their infant temperament. That confirms that biology affected their traits.

However, learning (specifically cognitive control) was also evident: Their outward behavior was similar to those with a more outgoing temperament, unless other factors caused serious emotional problems. Apparently, most of them had learned to override their initial temperament—

Continuity and change were also found in another study that found that angry infants were likely to make their mothers hostile toward them, and, if that happened, such infants became antisocial children. However, if the mothers were loving and patient, despite the difficult temperament of the children, hostile traits were not evident later on (Pickles et al., 2013).

The two trends evident in all these studies—

The reason both opposing interpretations thrive may depend more on the person drawing the conclusions than on the babies. Some people are inclined to accept things as they are. They are likely to emphasize inborn traits that do not change. Other people believe that change is always possible, even likely. They seek ways that early caregiving, or the social context, or even the national political structure, shape behavior.

Which of these two folk sayings are you more likely to tell your friends?

A leopard cannot change his spots,

or

If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.

137

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 4.1

1. What are the first emotions to appear in infants?

Crying and contentment are present from birth. The social smile appears around 6 weeks of age. Infants express social joy and laughter between 2 and 4 months of age.

Question 4.2

2. Why is it better for an infant to express anger than sadness?

Anger is usually triggered by frustration. Sadness, however, usually indicates withdrawal and is accompanied by an increase in the body’s production of cortisol, the primary stress hormone.

Question 4.3

3. What do 1-

Typical 1-

Question 4.4

4. How do emotions differ between the first and second year of life?

Emotions take on new strength during toddlerhood. For example, anger and fear become less frequent but more focused, targeted toward especially infuriating or terrifying experiences. Similarly, laughing and crying are louder and more discriminating. Social awareness develops, ushering in the new emotions of pride, shame, embarrassment, disgust, and guilt.

Question 4.5

5. How do family interactions and culture shape toddlers’ emotions?

The expression of pride, shame, embarrassment, disgust, and guilt requires social awareness and self-

Question 4.6

6. What evidence is there that toddlers become more aware of themselves?

Evidence can be found in the classic experiment in which 9-

Question 4.7

7. What is known about the impact of brain maturation on emotions?

The social smile, laughter, fear, self-

Question 4.8

8. What is not yet known about how brain maturation affects emotions?

It is still unknown how infant brains are molded by their environment and culture and how this affects their expression of emotions.

Question 4.9

9. How are memory and emotion connected?

All emotional reactions, particularly those connected to self-

Question 4.10

10. How does stress affect early brain development?

Excessive stress harms the developing brain. For example, the hypothalamus grows more slowly if an infant is often frightened.

Question 4.11

11. What three dimensions of temperament are evident in children?

Effortful control (regulating attention and emotion, self-

Question 4.12

12. What is the difference between temperament and personality?

Generally, personality traits (like honesty and humility) are learned, whereas temperamental traits (like aggression or shyness) are genetic. Of course, for every trait, nature and nurture interact.

Question 4.13

13. Why are temperament traits more apparent in some people than others?

Although temperament originates with genes, the expression of emotions over the life span is modified by experience—