Infant Day Care

Cultural variations in infant care are vast. No theory directly endorses any particular caregiving practice, but each of these theories has been used to justify radically different responses. This is particularly obvious in infant day care, a topic on which developmentalists disagree.

For ideological as well as economic reasons, center-

|

High-

|

Center care is scarce in South Asia, Africa, and Latin America, where many parents believe it would be harmful to infants’ well-

Many Choices, Many Cultures

Question 4.36

OBSERVATION QUIZ

What three things do you see that suggest good care?

Remontia Greene is holding the feeding baby in just the right position as she rocks back and forth—

It is estimated that about 134 million babies will be born each year from 2010 to 2021 (United Nations, 2013). Most newborns are cared for primarily or exclusively by their mothers. Allocare, especially by the father and grandmother, increases as the baby gets older. Daily care by a nonrelative, trained and paid to provide it, occurs for only about 15 percent of infants worldwide, a statistic that obscures the range from one culture to another.

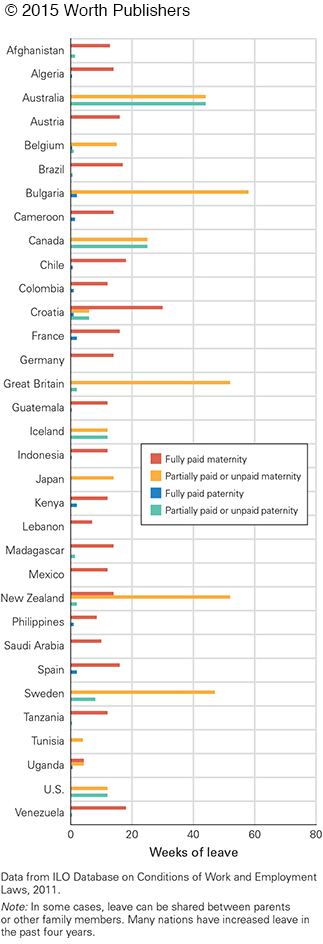

As discussed above, fathers worldwide increasingly take part in baby care, but some cultures still expect fathers to stay at a distance. Others favor equality (Shwalb et al., 2013). Most nations provide some paid leave for mothers who are in the workforce; some also provide paid leave for fathers; and several nations provide paid family leave that can be taken by either parent or shared between them.

The length of paid leave varies from a few days to about 15 months (see Figure 4.3). Those variations affect infant care, since an employee who loses money and a job is likely to go back to work as soon as possible after a baby is born.

The other crucial variable is whether day care is free, subsidized, or paid entirely by parents. When most child care is privately funded, quality varies a great deal. That makes it difficult to generalize about the effects of infant day care, since some day care is so much better than others.

NORTH AMERICA Only 20 percent of infants in the United States are cared for exclusively by their mothers (i.e., no other relatives or babysitters) throughout their first year. This is in contrast to Canada, which is similar to the United States in ethnic diversity but has far more generous maternal leave and lower rates of maternal employment.

In the first year of life, most Canadians are cared for only by their mothers (Babchishin et al., 2013). Obviously, these differences are affected by culture, economics, and politics more than by any universal needs of babies.

In the United States, some agencies send professional visitors to the homes of new parents, advising them about baby care. Mixed results come from such efforts—

Grandmother care seems particularly complex, as grandmothers vary in personality, competence, and dedication. For example, in most nations and centuries, infants were more likely to survive if their grandmothers were nearby, especially when they were newly weaned (Sear & Mace, 2008). The hypothesis is that grandmothers provided essential nourishment and protection. But in one era (northern Germany, 1720–

Mixed evidence can also be found for center care. Although all the research finds that cognitive development benefits from infant day care, several studies have suggested that children in early, extensive center care are somewhat more likely to develop externalizing problems by age 5—

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

The Mixed Realities of Center Day Care

A highly respected professional organization, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), recently revised its standards for care of babies from birth to 15 months, based on current research (NAEYC, 2014). Breast-

Many specific practices are recommended to keep infant minds growing and bodies healthy. For instance, “before walking on surfaces that infants use specifically for play, adults and children remove, replace, or cover with clean foot coverings any shoes they have worn outside that play area. If children or staff are barefoot in such areas, their feet are visibly clean.” Another recommendation is to “engage infants in frequent face-

Such responsive care, unfortunately, has not been routine for infants, especially those not cared for by their mothers. A large study in Canada found that infant girls seemed to develop equally well in various care arrangements.

However, Canadian boys from high-

The opposite was true for boys from low-

Research in the United States has also found that center care benefits children of low-

The social consequences were less stellar, however. Most analyses find that secure attachment to the mother was as common among infants in center care as among infants cared for at home. Like other smaller studies, the NICHD research confirms that the mother–

Infant day care seemed detrimental when the mother was insensitive and the infant spent more than 20 hours a week in a poor-

More recent work finds that high-

This raises another question: Might changing attitudes, female employment, and centers that reflect new research on infant development produce more positive results from center care? Or is there something about the connection between mother and baby that evolved over the millennia, as evolutionary theory might posit, that makes mother-

The link between infant day care and later psychosocial problems, although not found in every study, raises concern. For that reason, a large study in Norway is particularly interesting, as is recent research from Australia.

NORWAY In Norway, new mothers are paid at full salary to stay home with their babies for 47 weeks, and high-

In the United States, reliable statistics are not kept on center care for infants, but only 42 percent of all U.S. 3-

Longitudinal results in Norway find no detrimental results of infant center care that begins at age 1. (Too few children were in center care before their first birthday to find significant longitudinal results.) By kindergarten, Norwegian children in day care had slightly more conflicts with caregivers, but the authors suggest that may be the result of shy children becoming bolder as a result of day care (Solheim et al., 2013).

AUSTRALIA The attitudes of the culture and the mothers may influence the child. An intriguing example comes from Australia, where the government has recently attempted to increase the birth rate. Parents were given $5,000 for each newborn, parental leave is paid, and public subsidies provide child-

Parents are caught in the middle. For example, one Australian mother of a 12-

I spend a lot of time talking with them about his day and what he’s been doing and how he’s feeling and they just seem to have time to do that, to make the effort to communicate. Yeah they’ve really bonded with him and he’s got close to them. But I still don’t like leaving him there. And he doesn’t, to be honest … Because he’s used to sort of having, you know, parents.

[quoted in Boyd et al., 2013]

Developmentalists agree that both home quality and national context matter for infants. There is no agreed-

Many people believe that the practices of their own family or culture are best and that other patterns harm either the infant or the mother. This is another example of the difference-

A Stable, Familiar Pattern

No matter what form of care is chosen or what theory is endorsed, individualized care with stable caregivers seems best (Morrissey, 2009). Caregiver change is especially problematic for infants because each simple gesture or sound that a baby makes not only merits an encouraging response but also requires interpretation by someone who knows that particular baby well.

For example, “baba” could mean bottle, baby, blanket, banana, or some other word that does not even begin with b. This example is an easy one, but similar communication efforts—

A related issue is the growing diversity of baby care providers. Especially when the home language is not the majority language, parents hesitate to let people of another background care for their infants. That is one reason that, in the United States, immigrant parents often prefer care by relatives instead of by professionals (P. Miller et al., 2014). Relationships are crucial, not only between caregiver and infant but also between caregiver and parent (Elicker et al., 2014).

Particularly problematic is instability of nonmaternal care, as when an infant is cared for by a neighbor, a grandmother, a center, and then another grandmother, each for only a month or two. By age 3, children with unstable care histories are likely to be more aggressive than those with stable nonmaternal care, such as being at the same center with the same caregiver for years (Pilarz & Hill, 2014).

As is true of many topics in child development, questions remain. But one fact is without question: Each infant needs personal responsiveness. Someone should serve as a partner in the synchrony duet, a base for secure attachment, and a social reference who encourages exploration. Then infant emotions and experiences—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 4.37

1. What are the advantages of nonmaternal day care for the infant?

It allows mothers to return to work and provides (in good environments) safe spaces, appropriate learning and playing equipment, and trained providers to interact with children. The advantages appear most obvious around preschool age.

Question 4.38

2. What are the disadvantages of exclusive maternal care for the infant?

Possible disadvantages include a lack of paternal interaction with the infant, since in such a situation the father is usually working to support the family. Research also shows that for low-

Question 4.39

3. What might be the problem with infant day care?

One theory is that variations in day care arrangements are vast, and the quality of infant day care varies a great deal—

Question 4.40

4. Why are the effects of center care in Norway different from those in the United States?

Longitudinal results in Norway find no detrimental results of infant center care that begins at age one. By kindergarten, Norwegian children in day care had slightly more conflicts with caregivers, but the authors suggest that may be the result of shy children becoming bolder as a result of day care. Studies from the United States show that children in early, extensive center care are somewhat more likely to develop externalizing problems by age five—

Question 4.41

5. What are the costs and benefits of infant care by relatives?

Care by relatives may help the infant and the budget, but when it is the parents who are splitting the care, the arrangement may interfere with their ability to spend time together. Center day care is more expensive and varies greatly in quality. Grandmother care has been beneficial in most times and societies.

Question 4.42

6. What do infants need, no matter who cares for them or where care occurs?

Consistent caregivers seem to be the most important factor, whether the caregiver is a family member or a professional.