Body Changes

In early childhood, as in infancy, the body and mind develop according to powerful epigenetic forces. This means that nature and nurture continually interact: Growth is biologically driven and socially guided, experience-

Growth Patterns

Visualize an unsteady 24-

By the end of early childhood, the infant’s protruding belly, round face, short limbs, and large head are distant memories. The center of gravity has moved from the breast to the belly, enabling cartwheels, somersaults, and many other motor skills.

Mastery of gross and fine motor skills results not only from body growth and maturation but also from extensive, active play. Children take every opportunity to exercise their bodies, and the results are obvious. Many 2-

Most North American 5-

Adults need to make sure children have a safe space to play, with ample time, appropriate equipment, and active playmates. Children learn best from peers who demonstrate whatever the child is ready to try. Of course, culture and locale influence particulars: Some small children learn to ski, others to sail.

“Safe space to play” cannot be taken for granted. A century ago, children with varied skills played together in empty lots or fields without adult supervision, but now more than half the world’s children live in cities, often with crowded streets and no open space nearby. Gone are the days when parents told their children to go out and play, to return when hunger, rain, or nightfall brought them home. Now many parents fear strangers and traffic, keeping their 3-

That worries many childhood educators, who believe that children need space and freedom to play in order to develop well. Indeed, many agree that the environment is the third teacher, “because the environment is viewed as another teacher having the power to enhance children’s sense of wonder and capacity for learning” (Stremmel, 2012, p. 136). Nature outdoors allows more wonder than four walls inside.

Nutrition

Beyond space to play, another prerequisite for healthy development is good nutrition. Children are sometimes malnourished, even in nations with abundant food. The main reason is that small appetites are often satiated by unhealthy foods, crowding out needed vitamins.

Appetite decreases between ages 2 and 6 because young children naturally grow more slowly than they did as infants. Moreover, if children play less outside, they burn fewer calories. Instead of adjusting to this ecological change, many adults cajole, threaten, and bribe (“Eat all your dinner and you can have ice cream”).

Why do adults do that? Because they are still protecting children against famine. For example, 30 years ago in Brazil the most common nutritional problem was lack of food; now it is too much food (Monteiro et al., 2004). Low-

There is good news in the United States, however. Obesity among young children has declined markedly, from 14 percent in 2003–

NUTRITIONAL DEFICIENCIES Compared with the average child, those who eat more dark-

However, it is not easy to get 2-

Parents need to balance their concern for good nutrition with the child’s demand for sameness. This is another reason why toddlers need to be fed a variety of healthy foods, including some that are not the family’s usual fare, before the child refuses anything new.

FOOD ALLERGIES An added complication is that about 8 percent of U.S. children are allergic to a specific food, often a healthy one. Cow’s milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts (almonds, walnuts, etc.), soy, wheat, fish, and shellfish are the usual culprits.

For some foods, the allergic reaction is a rash or an upset stomach when too much of the food is consumed, but for others—

Some experts advocate total avoidance of the offending food—

Everyone agrees that when a child has a severe allergic reaction, someone should immediately inject epinephrine to stop the reaction. In 2012, all Chicago schools had EpiPens, which were used in dozens of emergencies (DeSantiago-

ORAL HEALTH Not surprisingly, tooth decay correlates with obesity; both result from too much sugar and too little fiber (Hayden et al., 2013). Sweetened beverages are usually the problem.

“Baby” teeth are replaced naturally from ages 6 to 10. The schedule is genetic, with girls a few months ahead of boys. However, the habit of tooth brushing and a visit to the dentist should begin years before the permanent teeth erupt. Poor oral health in early childhood harms those permanent teeth (forming below the first teeth) and can cause jaw malformation, chewing difficulties, and speech problems.

Teeth are affected by diet and illness, which means that the state of a young child’s teeth can alert the doctor or dentist to other health problems. The process works in reverse as well: Infected teeth can affect the rest of the child’s body.

Brain Development

The 2-

Although the brains and bodies of other animals are better than humans in some ways (chimpanzees can climb trees earlier and faster, for instance, and dogs can hear and smell better), no other animal has the intellectual capacities that humans do. From an evolutionary perspective, our brains allowed the human species to develop “a mode of living built on social cohesion, cooperation and efficient planning … survival of the smartest seems more accurate than survival of the fittest” (Corballis, 2011, p. 194).

executive function

The cognitive ability to organize and prioritize the many thoughts that arise from the various parts of the brain, allowing the person to anticipate, strategize, and plan behavior.

MATURATION OF THE PREFRONTAL CORTEX One major difference between human brains and the brains of other animals is a much larger frontal lobe, the site of the prefrontal cortex. That part of the brain supports what is called executive function, which is planning, reasoning, and anticipating. Executive function advances throughout childhood, including between ages 2 and 6. As a result:

Sleep becomes more regular.

Emotions become more nuanced and responsive.

Temper tantrums subside.

Uncontrollable laughter and tears are less common.

A convincing demonstration that something in the brain, not simply in experience, underlies these changes comes from a series of experiments with shapes and colors.

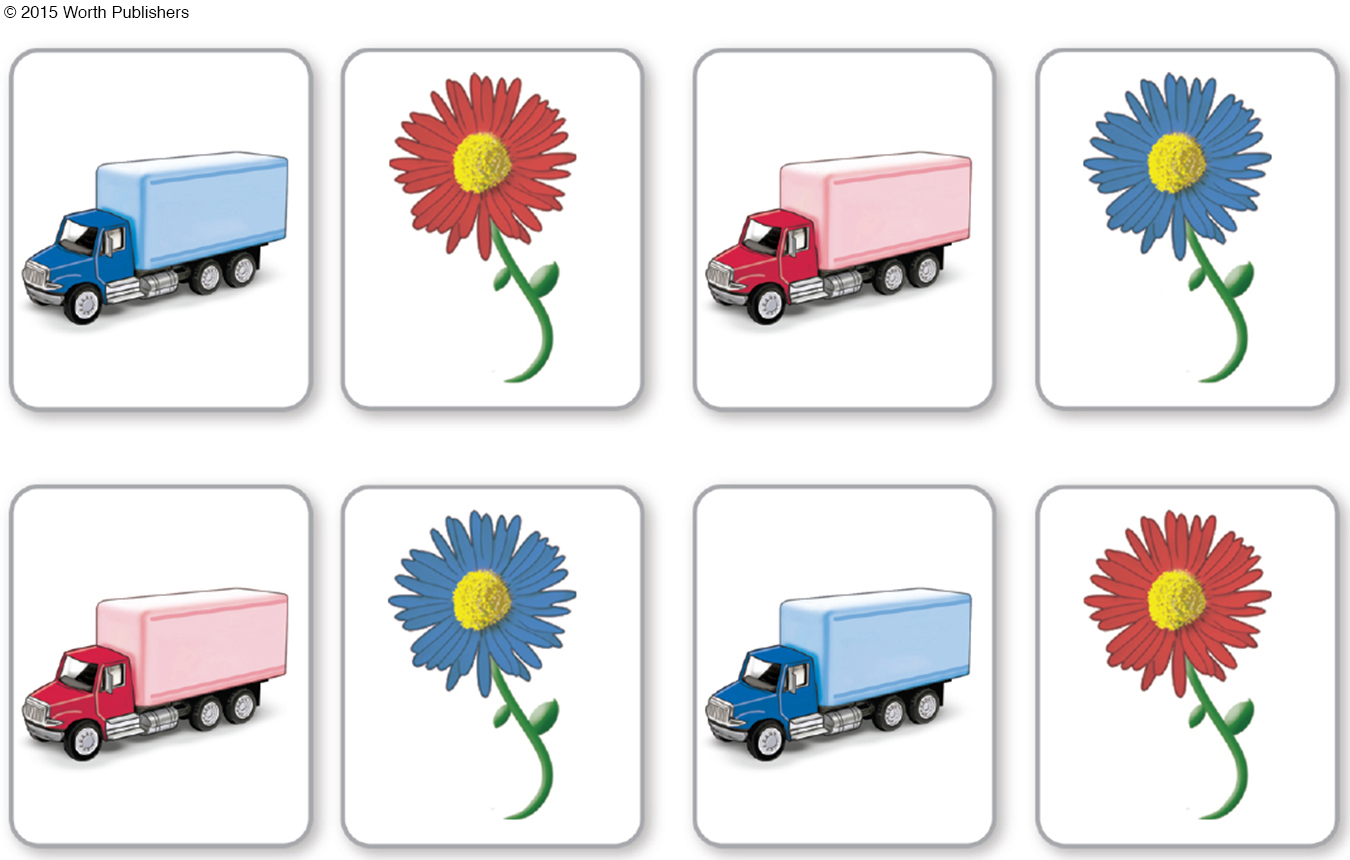

First, young children are presented with cards that have trucks or flowers, some red and some blue. They are asked to “play the shape game,” putting trucks in one pile and flowers in another. Three-

Then children are asked to “play the color game,” sorting the cards by color. Most children under age 4 fail. Instead, they sort by shape, as they had done before. This basic test has been replicated in many nations; 3-

When this result was first obtained, experimenters thought perhaps the children didn’t have enough experience to know their colors; so the scientists switched the order, first playing “the color game.” Most 3-

Researchers are looking into many possible explanations for this puzzling result (Marcovitch et al., 2010; Ramscar et al., 2013). Some try to teach children to be more advanced in this skill (Perone et al., 2015). All agree, however, that something in the brain matures at about age 4 that enables children to switch from one way of sorting objects to another.

corpus callosum

A long, thick band of nerve fibers that connects the left and right hemispheres of the brain and allows communication between them.

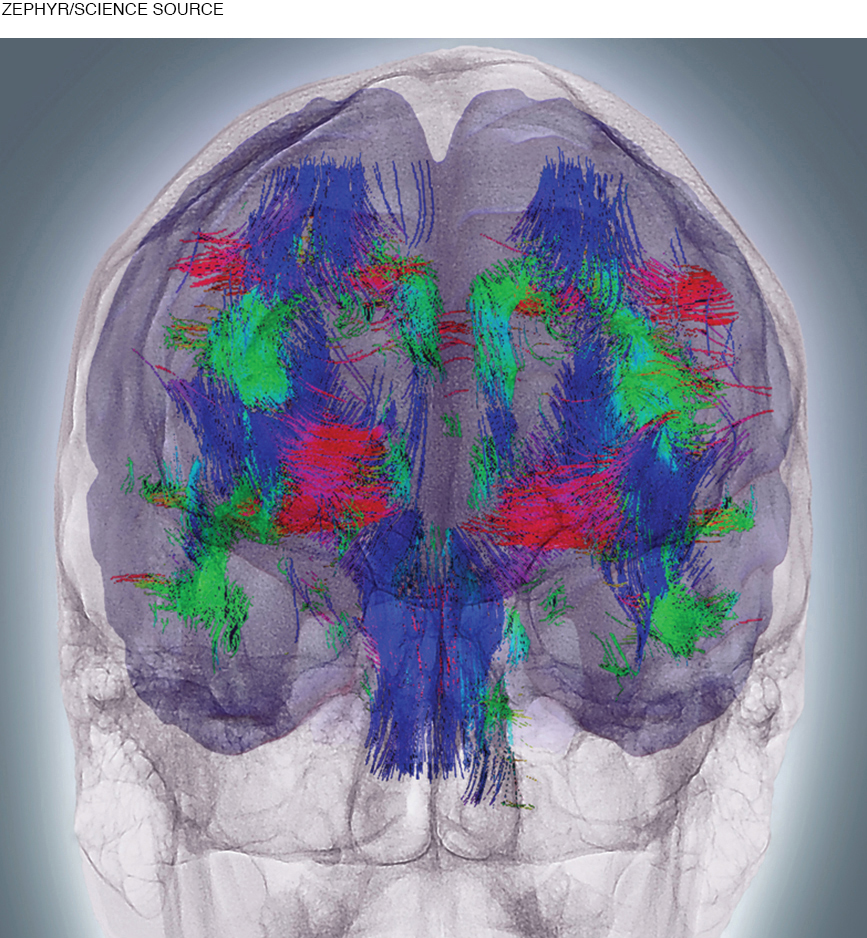

THE BRAIN’S CONNECTED HEMISPHERES One part of the brain that grows and myelinates rapidly during early childhood is the corpus callosum, a long, thick band of nerve fibers that connects the left and right sides of the brain. Growth of the corpus callosum makes communication between the hemispheres more efficient, allowing children to coordinate the two sides of their brains and hence, both sides of their bodies.

lateralization

Literally, sidedness, referring to the specialization in certain functions by each side of the brain, with one side dominant for each activity. The left side of the brain controls the right side of the body, and vice versa.

Each side of the body and brain specializes. This is lateralization: literally, “sidedness.” The entire human body is lateralized, apparent not only in handedness but also in the feet, the eyes, the ears, and the brain itself. People prefer to kick a ball, wink an eye, or listen on the phone with their preferred foot, eye, or ear. Genes, prenatal hormones, and early experiences all affect which side does what. Lateralization advances with development of the corpus callosum (Kolb & Whishaw, 2013).

Serious disorders result when the corpus callosum fails to develop, which leads to many deficits, including intellectual disability (Cavalari & Donovick, 2014). Undeveloped corpus callosum is one of several possible causes of autism spectrum disorder (Frazier et al., 2012; Floris et al., 2013).

THE LEFT-

Many cultures try to make every child right-

Many cultures imply that being right-

The design of doorknobs, scissors, baseball mitts, instrument panels, and other objects favor the right hand. (Some manufacturers have special versions for lefties, but few young children know to ask for them.) In many Asian and African cultures, only the left hand is used for wiping after defecation; it is an insult to give someone anything with that “dirty” hand.

For many reasons, developmentalists advise against switching a child’s handedness. A disproportionate number of artists, musicians, political leaders, and sports stars were/are left-

Fortunately, left-

THE WHOLE BRAIN Typically, the brain’s left half controls the body’s right side as well as areas dedicated to logical reasoning, detailed analysis, and the basics of language. The brain’s right half controls the body’s left side and areas dedicated to emotional and creative impulses, including appreciation of music, art, and poetry.

This left–

Video: Brain Development Animation: Process of Myelination

Usually, both sides of the brain are involved in every skill. That is why the maturation of the corpus callosum is crucial. For example, no 2-

myelination

The process by which axons become coated with myelin, a fatty substance that speeds the transmission of nerve impulses from neuron to neuron.

FASTER THINKING Another significant brain development in early childhood is increased myelination, as the axons of the brain increase in myelin (the white matter of the brain), a fatty coating that speeds signals between neurons (see Figure 5.2).

Although myelination continues for decades, the effects are especially apparent in early childhood (Silk & Wood, 2011). The areas of the brain that show the greatest early myelination are the motor and sensory areas (Kolb & Whishaw, 2013), so preschoolers react more quickly to sounds and sights with every passing year.

Speed of thought from axon to neuron becomes pivotal when several thoughts must occur in rapid succession. By age 6, most children can see an object and immediately name it, catch a ball and throw it, write their ABCs in proper sequence, and so on. In fact, rapid naming of letters and objects—

Of course, adults must be patient when listening to young children talk, helping them get dressed, or watching them write each letter of their names. Everything is done more slowly by 6-

IMPULSIVENESS AND PERSEVERATION Neurons have only two kinds of impulses: on–

impulse control

The ability to postpone or deny the immediate response to an idea or behavior.

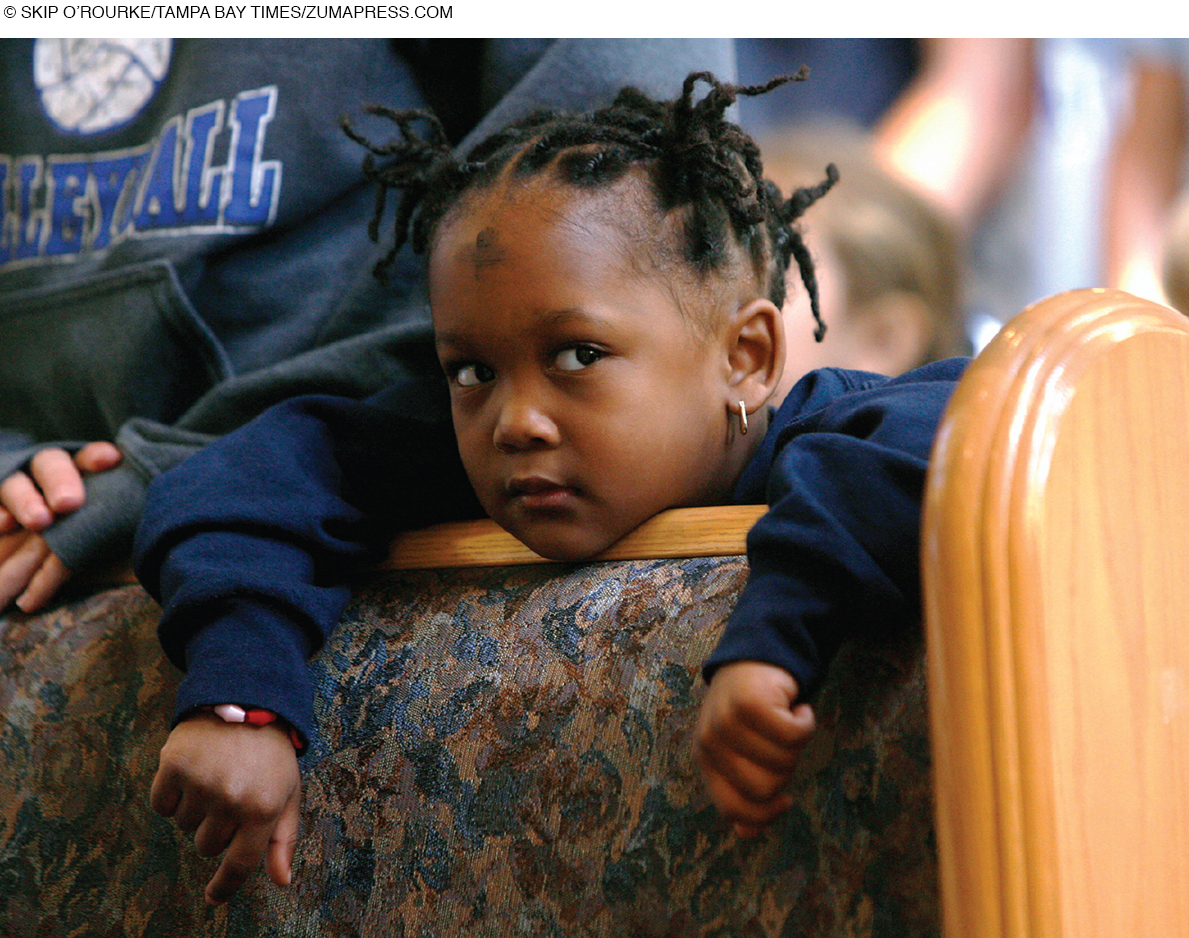

Many young children are notably unbalanced. They are impulsive, flitting from one activity to another. Some 5-

perseveration

The tendency to persevere in, or stick to, one thought or action for a long time.

Some preschoolers have the opposite problem: It is hard to get them to switch from one task to another. That tendency is called perseveration, when a person perseveres, or sticks to, one thought or action. Perseveration was evident in the card-

Perseveration may make a young child repeat one question again and again. A tantrum that occurs when a child is told to put away a toy may itself perseverate, because the crying does not stop even if the reason for it stops. Crying may become uncontrollable because the child is stuck in the emotion. On a happier note, some young children start laughing and then cannot stop!

Impulsiveness and perseveration are opposite manifestations of the same underlying cause: immaturity of the prefrontal cortex. No young child is perfect at regulating attention; impulsiveness and perseveration are evident. A longitudinal study of children from ages 3 to 6 found a steady increase in ability to pay attention, which led to more learning and better emotional control (fewer outbursts or tears) (L. Metcalfe et al., 2013).

Children with attention-

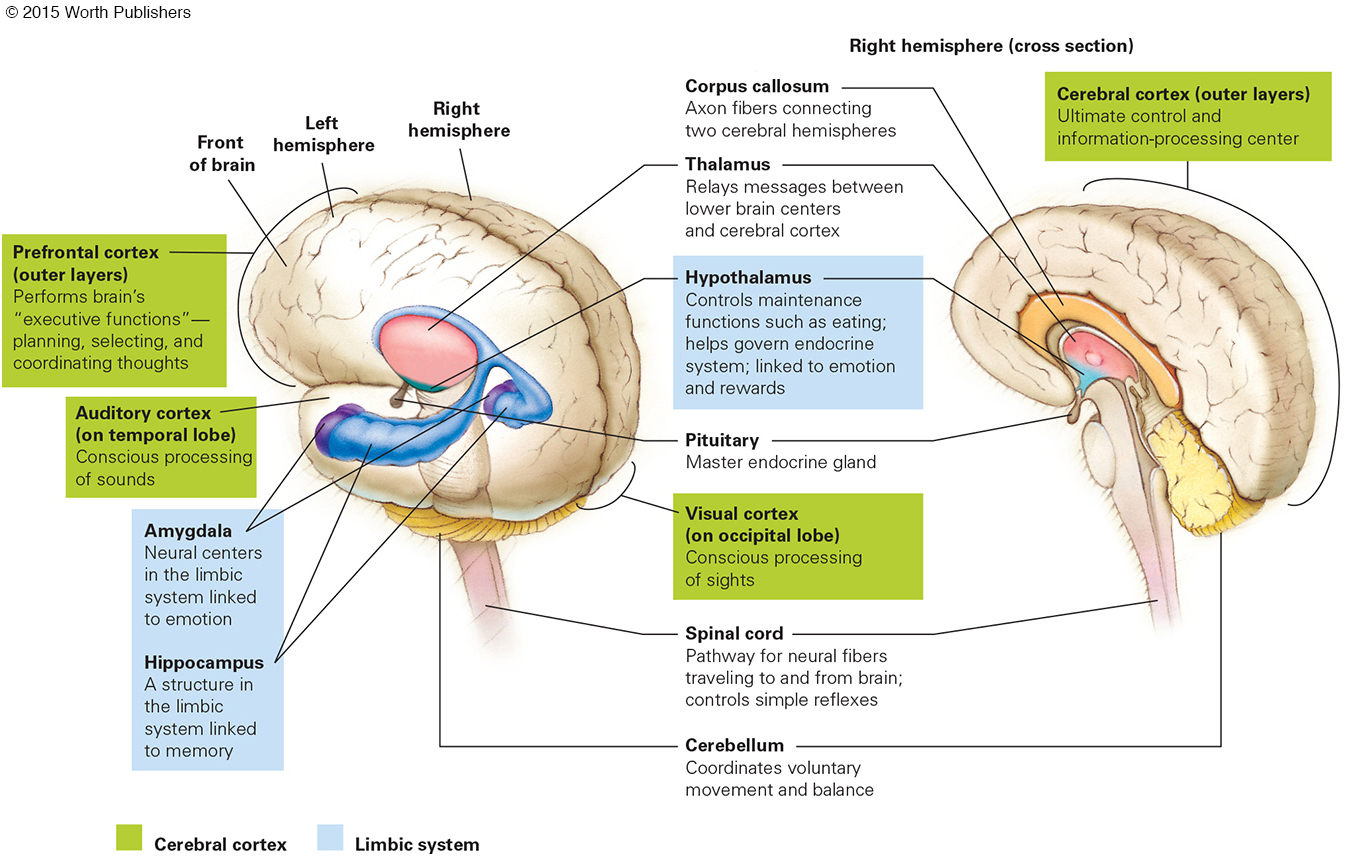

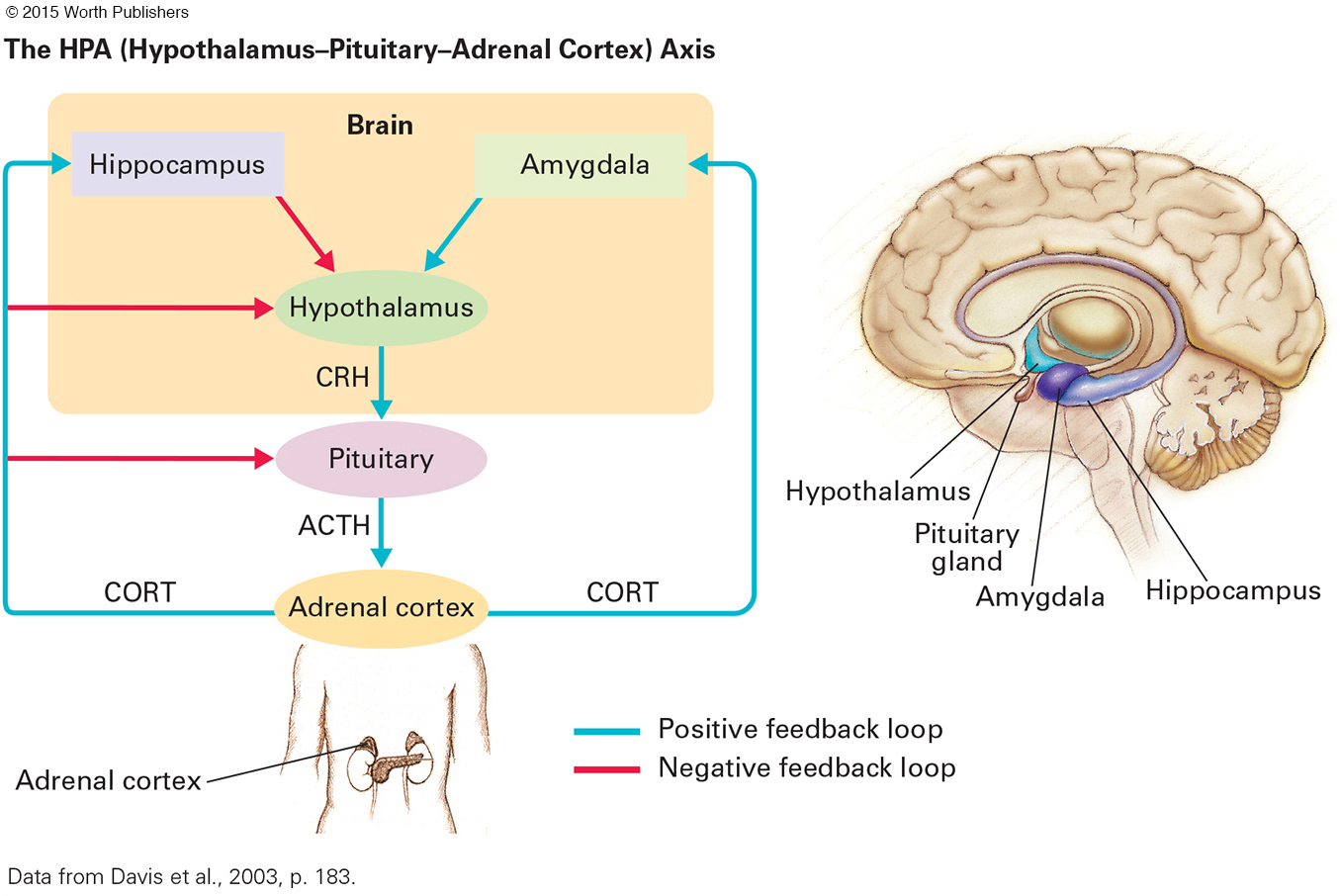

EMOTIONS AND THE BRAIN Now we turn to another region of the brain, sometimes called the limbic system, the major system for emotions. Emotional expression and regulation advance during early childhood because of three parts of the limbic system—

amygdala

A tiny brain structure that registers emotions, particularly fear and anxiety.

The amygdala is a tiny structure deep in the brain, about the same shape and size as an almond. It registers emotions, both positive and negative, especially fear (Kolb & Whishaw, 2013). Increased amygdala activity is one reason some young children have terrifying nightmares or sudden terrors, overwhelming the prefrontal cortex. A child may refuse to enter an elevator or may be hysterical, half-

hippocampus

A brain structure that is a central processor of memory, especially memory for locations.

Another structure in the emotional network is the hippocampus, located next to the amygdala. A central processor of memory, especially memory for locations, the hippocampus responds to the fears from the amygdala by summoning memory. A child can remember, for instance, whether previous elevator riding was scary or fun.

Early memories of location are fragile because the hippocampus is still developing. Even in adulthood, emotional memories from early childhood can interfere with rational thinking: An adult might have a panic attack but not know why.

hypothalamus

A brain area that responds to the amygdala and the hippocampus as well as various experiences to produce hormones that activate other parts of the brain and body.

A third part of the limbic system, the hypothalamus, responds to signals from the amygdala (arousing) and from the hippocampus (usually dampening) by producing cortisol, oxytocin, and other hormones that activate the brain and body (see Figure 5.3). Ideally, this occurs in moderation. Both temperament and parental responses affect whether or not the hypothalamus will overreact, making the preschooler overly anxious—

As the limbic system develops, young children watch their parents’ emotions closely. If a parent looks worried when entering an elevator, the child may cling to the parent when the elevator moves. If this recurs often, the child may become hypersensitive to elevators, as fear from the amygdala joins memories from the hippocampus, increasing cortisol production via the hypothalamus.

If, instead, the parent makes elevator-

THINK CRITICALLY: How might an understanding of brain development help a teacher who takes 3-

Knowing the varieties of fears and joys is helpful when an adult takes a group of young children on a trip. To stick with the elevator example, one child might be terrified while another child might rush forward, pushing the “close” button before the teacher enters.

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 5.1

1. How are growth rates, body proportions, and motor skills related during early childhood?

From ages 2 to 6, weight and height increase, and the relation between the two changes. Mastery of gross and fine motor skills results not only from body growth and maturation but also from extensive, active play. Brain maturation, motivation, and guided practice undergird all these motor skills.

Question 5.2

2. Why do many children in developed nations suffer from malnutrition?

Children are sometimes malnourished, even in nations with abundant food. The main reason is that small appetites are often satiated by unhealthy foods, crowding out needed vitamins.

Question 5.3

3. What is changing in rates of early childhood obesity and why?

Obesity among young children in the United States has declined markedly, probably due to public education combined with parental action.

Question 5.4

4. When (if ever) and why should a left-

For many reasons, developmentalists advise against switching a child’s handedness. Trying to change handedness may interfere with brain function and lateralization.

Question 5.5

5. What do children need to learn various motor skills?

Usually, both sides of the brain are involved in every skill. That is why the maturation of the corpus callosum is crucial. For example, no 2-

Question 5.6

6. How does myelination advance skill development?

Myelination happens when the axons of the brain increase in myelin, which is a fatty coating that speeds signals between neurons. The motor and sensory areas of the brain show the greatest signs of early myelination, which would aid in skill development.

Question 5.7

7. How is the corpus callosum crucial for learning?

Growth of the corpus callosum makes communication between hemispheres more efficient, allowing children to coordinate both sides of the brain and body.

Question 5.8

8. What do impulse control and perseveration have in common?

Impulsiveness and perseveration are opposite manifestations of the same underlying cause—

Question 5.9

9. What is the limbic system?

The limbic system is the major system for emotions, and it has three parts: the amygdala, hippocampus, and hypothalamus.

Question 5.10

10. What is the amygdala?

The amygdala is a tiny almond-

Question 5.11

11. What does the hippocampus do?

Located next to the amygdala, the hippocampus is the central processor of memory, especially for location.

Question 5.12

12. What does the hypothalamus do?

The hypothalamus responds to signals from the amygdala and the hippocampus by producing cortisol, oxytocin, and other hormones that activate the brain and body.