Emotional Development

emotional regulation

The ability to control when and how emotions are expressed.

Children gradually learn when and how to express emotions, becoming more capable in every aspect of their lives. Controlling the expression of their feelings, called emotional regulation, is the preeminent psychosocial task between ages 2 and 6. Emotional regulation is a lifelong endeavor, with early childhood crucial for its development (Gross, 2014; Lewis, 2013).

By age 6, signs of emotional regulation are evident. Most children can be angry but not explosive, frightened but not terrified, sad but not inconsolable, anxious but not withdrawn, proud but not boastful. Depending on training and temperament, some emotions are easier to control than others, but even temperamentally angry or fearful children learn to regulate their emotions (Moran et al., 2013, Tan et al., 2013).

Cultural differences are apparent: Children may be encouraged to laugh/cry/yell or, the opposite, to hide emotions. Some adults guffaw, slap their knees, and stomp their feet for joy; others use their hands to cover their mouths if a smile spontaneously appears. No matter what the specifics, parents everywhere teach emotional regulation (Kim & Sasaki, 2014).

effortful control

The ability to regulate one’s emotions and actions through effort, not simply through natural inclination.

Emotional regulation is also called effortful control (Eisenberg et al., 2014), a term which highlights that controlling outbursts is not easy, in childhood or later, for reasons that are biological as well as experiential. Effortful control is more difficult when people—

I see this in my own life. My 5-

Initiative Versus Guilt

initiative versus guilt

Erikson’s third psychosocial crisis, in which children undertake new skills and activities and feel guilty when they do not succeed at them.

Emotional regulation is one of the skills children acquire during Erikson’s third developmental stage, initiative versus guilt. Initiative can mean several things—

Usually, North American parents encourage enthusiasm, effort, and pride in their 2-

Guidance, yes; brutal honesty, no. Preschool children are usually proud of themselves, overestimating their skills. As one team expressed it:

Compared to older children and adults, young children are the optimists of the world, believing they have greater physical abilities, better memories, are more skilled at imitating models, are smarter, know more about how things work, and rate themselves as stronger, tougher, and of higher social standing than is actually the case.

[Bjorklund & Ellis, 2014, p. 245]

Question 6.1

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Does this mother deserve praise?

Yes—

That helps them try new things, which advances learning of all kinds. As Erikson predicted, their optimistic self-

If young children know the limits of their ability, they will not imagine becoming an NBA forward, a Grammy winner, a billionaire inventor. But that might discourage them from trying to learn new things (Bjorklund & Ellis, 2014). Initiative is a driving force for young children, and that is as it should be.

PRIDE AND PREJUDICE In the United States, pride quickly includes gender, size, and heritage. Girls are usually happy to be girls; boys to be boys; both are glad they aren’t babies. “Crybaby” is an insult; praise for being “a big kid” is welcomed; pride in doing something better than a younger child is expressed, even when it makes the younger child feel sad.

THINK CRITICALLY: At what age, if ever, do people understand when pride becomes prejudice?

Many young children believe that whatever they are is good. They feel superior to children of the other sex, or of another nationality or religion. This arises because of maturation: Cognition enables children to understand group categories, not only of ethnicity, gender, and nationality, but even categories that are irrelevant. They remember more about cartoon characters whose names begin with the same letter as theirs do (Ross et al., 2011).

One amusing example occurred when preschoolers were asked to explain why one person would steal from another, as occurred in a story about two fictional tribes, the Zaz and the Flurps. As you would expect from theory-

“Why did a Zaz steal a toy from a Flurp?”

“Because he’s a Zaz, but he’s a Flurp … They’re not the same kind …?”

“Why did a Zaz steal a toy from a Zaz?”

“Because he’s a very mean boy.”

[Rhodes, 2013, p. 259]

Brain Maturation

The new initiative that Erikson describes results from myelination of the limbic system, growth of the prefrontal cortex, and a longer attention span—

Normally, neurological advances in the prefrontal cortex at about age 4 or 5 make children less likely to throw tantrums, pick fights, or giggle during prayer. Throughout early childhood, violent outbursts, uncontrolled crying, and terrifying phobias (irrational, crippling fears) diminish.

The capacity for self-

In one study, researchers asked children to wait eight minutes while their mothers did some paperwork before opening a wrapped present in front of them (Cole et al., 2010). The children used strategies to help them wait, including distractions and private speech.

Video Activity: Can Young Children Delay Gratification? illustrates how most young children are unable to overcome temptation even when promised an award for doing so.

Keisha was one of the study participants:

“Are you done, Mom?” … “I wonder what’s in it” … “Can I open it now?”

Each time her mother reminds Keisha to wait, eventually adding, “If you keep interrupting me, I can’t finish and if I don’t finish …” Keisha plops in her chair, frustrated. “I really want it,” she laments, aloud but to herself. “I want to talk to mommy so I won’t open it. If I talk, Mommy won’t finish. If she doesn’t finish, I can’t have it.” She sighs deeply, folds her arms, and scans the room…. The research assistant returns. Keisha looks at her mother with excited anticipation. Her mother says, “OK, now.” Keisha tears open the gift.

[Cole et al., 2010, p. 59]

This is a more recent example of the famous marshmallow test. Children could eat one marshmallow immediately or get two marshmallows if they waited—

Of course, this is correlation, not causation: Some preschoolers who did not wait became successful in later life. Many factors influence emotional regulation:

Maturation matters. Three-

year- olds are notably poor at impulse control. By age 6 they are better, and effortful control continues to improve throughout childhood. Learning matters. In the zone of proximal development, children learn from mentors, who offer tactics for delaying gratification.

Culture matters. In the United States many parents tell their children not to be afraid; in Japan they tell them not to be too proud; in the Netherlands, not to be too moody. Children try to do what their culture asks.

Motivation

Motivation is the impulse that propels someone to act. It comes either from a person’s own desires or from the social context.

intrinsic motivation

A drive, or reason to pursue a goal, that comes from inside a person, such as the joy of reading a good book.

Intrinsic motivation arises from within, when people do something for the joy of doing it: A musician might enjoy making music even if no one else hears it. Intrinsic motivation is thought to advance creativity, innovation, and emotional well-

extrinsic motivation

A drive, or reason to pursue a goal, that arises from the need to have one’s achievements rewarded from outside, perhaps by earning money or praise.

Extrinsic motivation comes from outside the person, when people do something to gain praise or some other reinforcement. A musician might play for applause or money. Social rewards are powerful lifelong: Four-

Intrinsic motivation is crucial for children. They play, question, and explore for the sheer joy of it. That serves them well. A study found that 3-

Child-

imaginary friends

Make-

Intrinsic motivation is apparent when children invent dialogues for their toys, concentrate on creating a work of art or architecture, or converse with imaginary friends. Such conversations with invisible companions are rarely encouraged by adults (thus no extrinsic motivation), but from about age 2 to 7, imaginary friends are increasingly common. Children know their imaginary friends are invisible and pretend, but conjuring them up meets various intrinsic psychosocial needs (M. Taylor et al., 2009).

The distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation may be crucial in understanding how and when to praise something the child has done. Praise may be effective when it is connected to the particular production, not to a general trait. For example, the adult might say, “You worked hard and did a good drawing,” not “You are a great artist.” The goal is to help the child feel happy that effort paid off. That motivates future action (Zentall & Morris, 2010).

In a set of experiments which suggest that specific praise for effort is better than generalized statements, some 4-

By contrast, other children were told that one particular child was good at the game. That led them to believe that personal effort mattered. That belief was motivating; their scores were higher than those told that boys or girls in general were good.

Play

Play is timeless and universal—

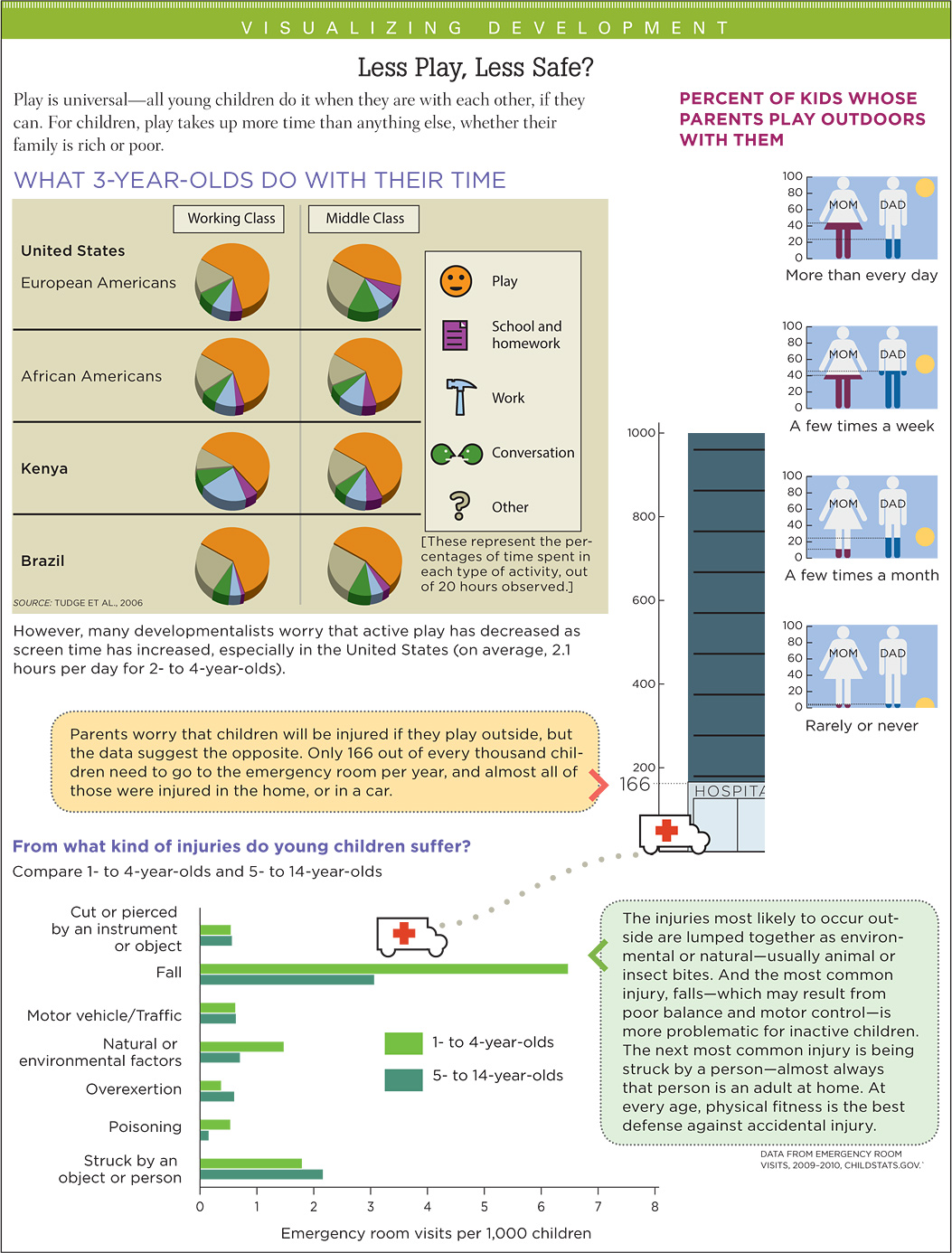

This controversy underlies many of the disputes regarding preschool education, which increasingly stresses academic skills. One consequence is that “play in school has become an endangered species” (Trawick-

Some educators want children to play less in order to focus on reading and math; others predict emotional and academic problems for children who rarely play. If children are kept quiet for a long time, they tend to play more vigorously when they finally have the chance (Pellegrini, 2013). For people of all ages, taking a break from concentrated intellectual work enhances learning.

PLAYMATES There are two general kinds of play, pretend play that often occurs when a child is alone and social play that occurs with playmates. One meta-

The researchers report that evidence is weak or mixed regarding pretend play but that social play has much to commend it. If social play is prevented, children are less happy and less able to learn, which suggests that social play is one way that children develop their minds and social skills.

Young children play best with peers, that is, people of about the same age and social status. Although infants are intrigued by other children, most infant play is either solitary or with a parent. Some maturation is required for play with peers (Bateson & Martin, 2013).

Such an advance can be seen over the years of early childhood. Toddlers are too self-

Parents have an obvious task: Find peers and arrange play partners. Of course, some parents play with their children, which benefits both generations. But even the most playful parent is outmatched by another child at negotiating the rules of tag, at play-

Parents in some cultures consider play important and willingly engage in games and dramas. In other places, sheer survival takes time and energy, and children must help by doing chores. In those places, if children play, it is with each other, not with adults who spend all their energy on basic tasks (Kalliala, 2006; Roopnarine, 2011).

Question 6.2

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Does kicking a soccer ball, as shown above, require fine or gross motor skills?

Although controlling the trajectory of a ball with feet is a fine motor skill, these boys are using gross motor skills—

THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT As children grow older, play becomes more social, influenced by brain maturation, playmate availability, and the physical setting. One developmentalist bemoans the twenty-

His opinion may be extreme, but it is echoed in more common concerns. As you remember, one dispute in preschool education is the proper balance between unstructured, creative play and teacher-

That was true in the United States a century ago. In 1932, the American sociologist Mildred Parten described the development of five stages of social play, each more advanced than the previous one:

Solitary play: A child plays alone, unaware of any other children playing nearby.

Onlooker play: A child watches other children play.

Parallel play: Children play with similar objects in similar ways but not together.

Associative play: Children interact, sharing material, but their play is not reciprocal.

Cooperative play: Children play together, creating dramas or taking turns.

Parten thought that progress in social play was age-

THINK CRITICALLY: Is “play” an entirely different experience for adults than for children?

Research on contemporary children finds much more age variation, perhaps because family size is smaller and parents invest heavily in each child. Many Asian parents successfully teach 3-

ACTIVE PLAY Children need physical activity to develop muscle strength and control. Peers provide an audience, role models, and sometimes competition. For instance, running skills develop best when children chase or race each other, not when a child runs alone. Gross motor play is favored among young children, who enjoy climbing, kicking, and tumbling (Case-

Active social play—

Among nonhuman primates, deprivation of social play warps later life, rendering some monkeys unable to mate, to make friends, or even to survive alongside other monkeys (Herman et al., 2011; Palagi, 2011). Might the same be true for human primates?

rough-

Play that seems to be rough, as in play wrestling or chasing, but in which there is no intent to harm.

The most common form of active play is called rough-

If a young male monkey wanted to play, he would simply catch the eye of a peer and then run a few feet away. This invitation to rough-

When these scientists returned to London, they saw that their own children, like baby monkeys, engaged in rough-

Rough-

Many scientists think that rough-

sociodramatic play

Pretend play in which children act out various roles and themes in plots or roles that they create.

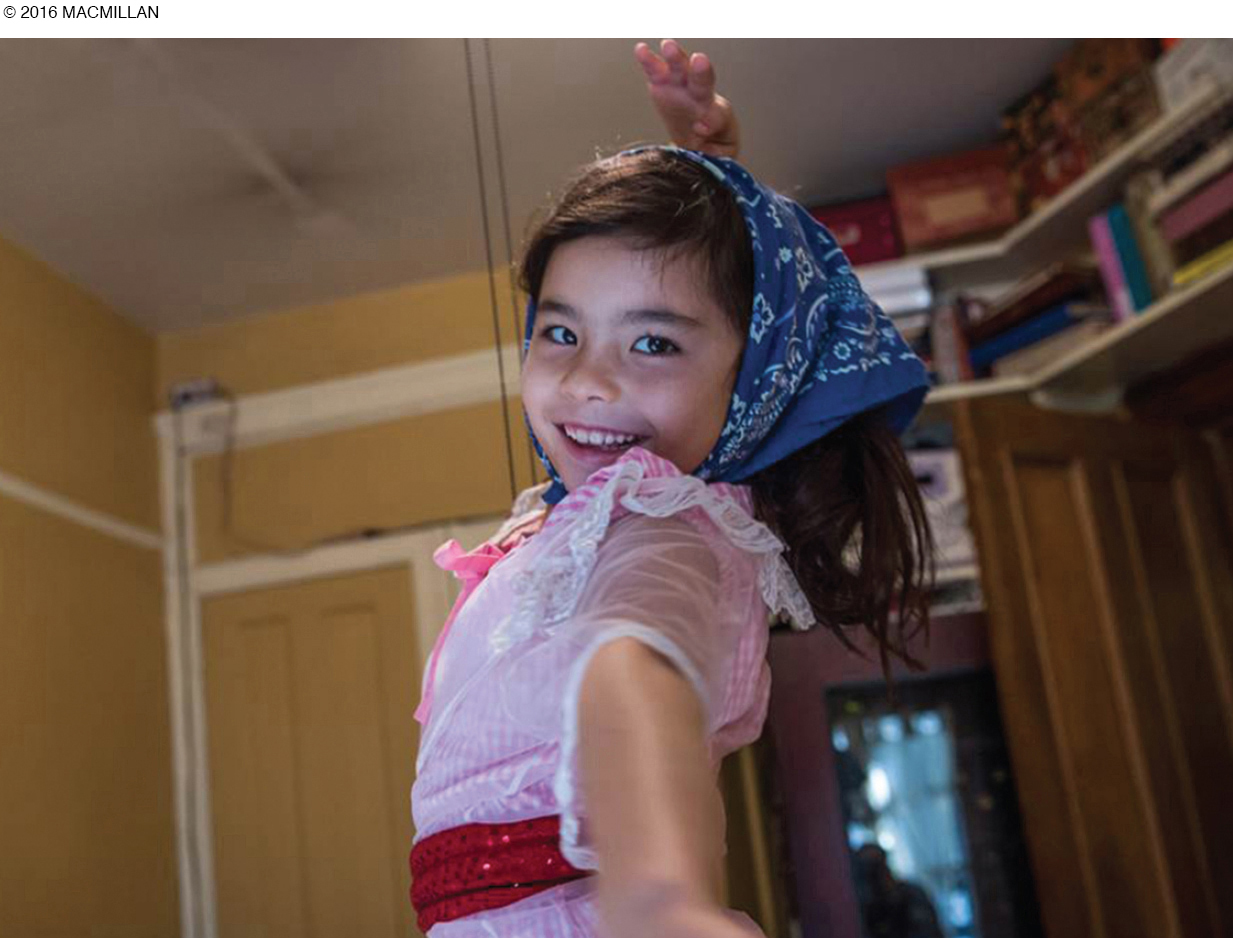

Another major type of active play is sociodramatic play, in which children act out various roles and plots. Through such acting, children:

Explore and rehearse social roles

Learn to explain their ideas and persuade playmates

Page 209Practice emotional regulation by pretending to be afraid, angry, brave, and so on

Develop self-

concept in a nonthreatening context

Sociodramatic play builds on pretending, which emerges in toddlerhood. But preschoolers do more than pretend; they combine their imagination with that of their friends, advancing in theory of mind (Kavanaugh, 2011). As they become conscious of gender differences, preschoolers also prefer to play with children of their own sex. Their play differs by gender.

This was evident in a day-

Tuomas: … and now he [Joni] would take me and would hang me…. this would be the end of all of me.

Joni: Hands behind!

Tuomas: I can’t help it … I have to. [The two other boys follow his example.]

Joni: I would put fire all around them.

[All three brave boys lie on the floor with hands tied behind their backs. Joni piles mattresses on them, and pretends to light a fire, which crackles closer and closer.]

Tuomas: Everything is lost!

[One boy starts to laugh.]

Petterl: Better not to laugh, soon we will all be dead…. I am saying my last words.

Tuomas: Now you can say your last wish…. And now I say I wish we can be terribly strong.

[At that point, the three boys suddenly gain extraordinary strength, pushing off the mattresses and extinguishing the fire. Good triumphs over evil, but not until the last moment, because, as one boy explains, “Otherwise this playing is not exciting at all.”]

[adapted from Kalliala, 2006, p. 83]

Often boys’ sociodramatic play includes danger and then victory over evil. By contrast, girls typically act out domestic scenes, with themselves as the adults. In the same day-

The prevalence of sociodramatic play varies by culture, with parents often following cultural norms. Some cultures find make-

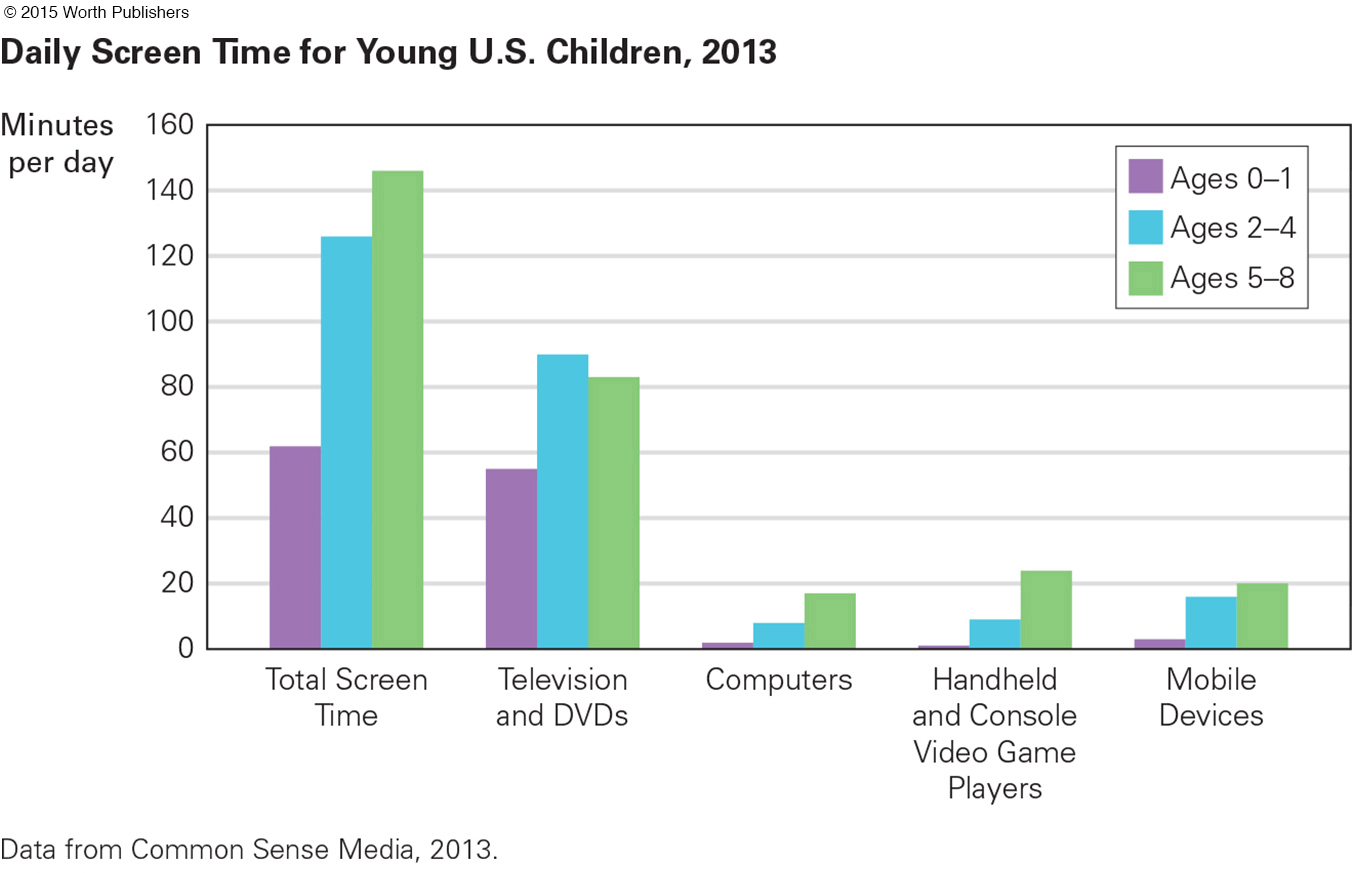

That children copy superheroes and villains from video screens is troubling to many developmentalists, who prefer dramas from a child’s imagination. This is not to say that screen time is necessarily bad: Children learn from videos, especially if adults watch with them. However, children rarely select educational programs over fast-

Canadian as well as U.S. organizations of professionals in child welfare (e.g., pediatricians) suggest zero screen time for children under age 2 and less than an hour a day for 2-

The data trouble professionals for many reasons. One is simply time—

Video: The Impact of Media in Early Childhood

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 6.3

1. How might protective optimism lead to a child’s acquisition of new skills and competencies?

Young children’s self-

Question 6.4

2. How would a child’s self-

As Erikson predicted, a child’s optimistic self-

Question 6.5

3. What is an example (not in the text) of intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation?

Answers will vary, but a possible answer is mowing a lawn. An intrinsic motivation for mowing a lawn may be finding enjoyment in the fresh air and physical activity. An extrinsic motivation may be getting paid by a neighbor to keep his lawn mowed for him.

Question 6.6

4. What are children thought to gain from play?

Many developmentalists believe that play is the most productive as well as the most enjoyable activity that children undertake. Social play is one way that children develop their minds and social skills. As they become better playmates, young people learn emotional regulation, empathy, and cultural understanding.

Question 6.7

5. Why might playing with peers help children build muscles and develop self-

Peers provide an audience, role models, and sometimes competition. For instance, running skills develop best when children chase or race each other, not when a child runs alone. Active social play—

Question 6.8

6. What do children learn from rough-

Many scientists think that rough-

Question 6.9

7. What do children learn from sociodramatic play?

Children learn to explore and rehearse social roles; to explain their ideas and persuade playmates; to practice emotional regulation by pretending to be afraid, angry, brave, and so on; and to develop self-

Question 6.10

8. Why do many experts want to limit children’s screen time?

The more that children are glued to screens, especially when the screen is their own hand-