Challenges for Caregivers

Limiting screen time is only one of dozens of challenges for caregivers. How caregivers respond depends on the particular temperament of the child, on the culture, and on what the caregiver thinks is best.

Styles of Caregiving

Question 6.11

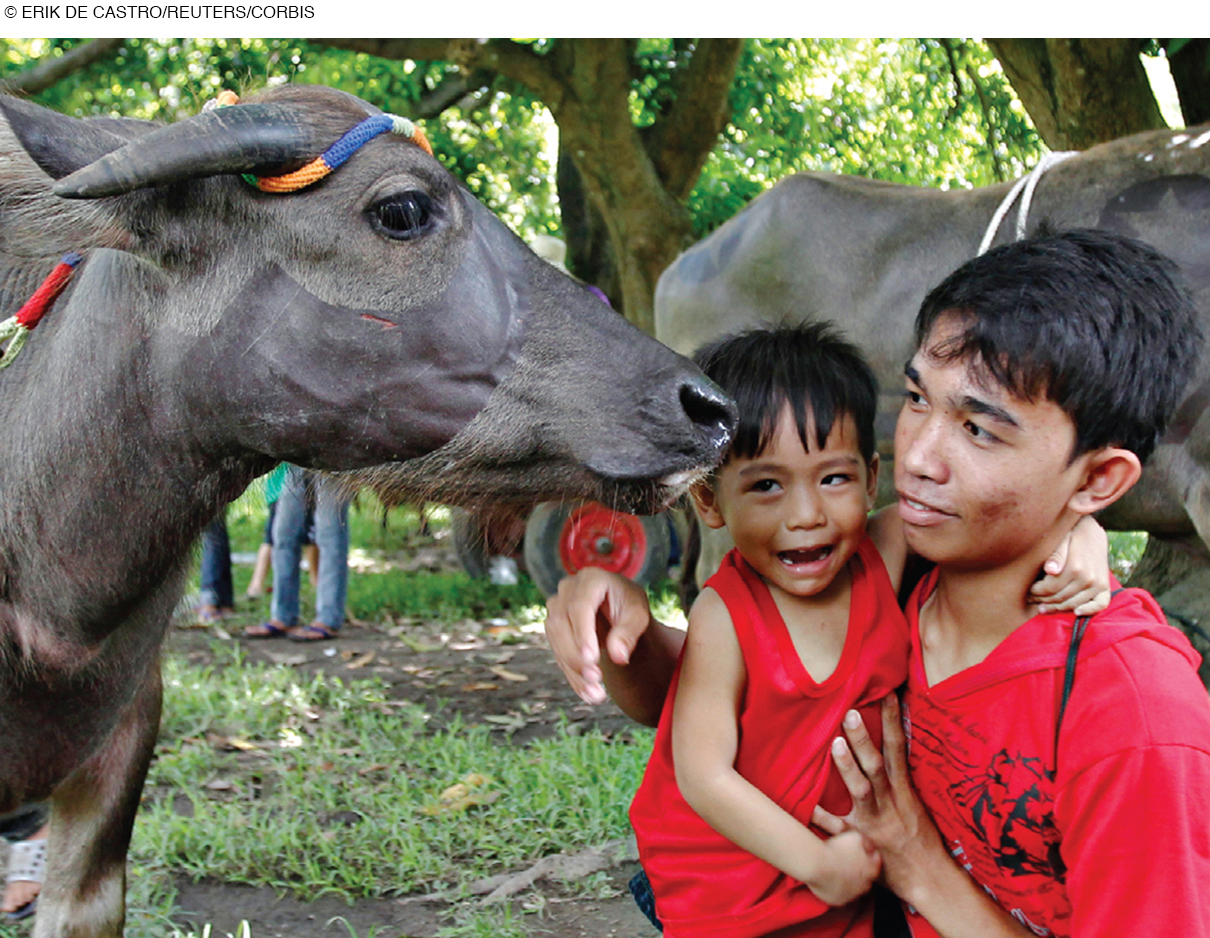

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Is the father above authoritarian, authoritative, or permissive?

It is impossible to be certain based on one moment, but the best guess is authoritative. He seems patient and protective, providing comfort and guidance, neither forcing (authoritarian) nor letting the child do whatever he wants (permissive).

Although thousands of researchers have traced the effects of parenting on child development, the work of one person, 50 years ago, continues to be influential. In her original research, Diana Baumrind (1967, 1971) studied 100 preschool children, all from California, almost all middle-

Baumrind found that parents differed on four important dimensions:

Expressions of warmth. Some parents are warm and affectionate; others, cold and critical.

Strategies for discipline. Parents vary in how they explain, criticize, persuade, and punish.

Communication. Some parents listen patiently; others demand silence.

Expectations for maturity. Parents vary in expectations for responsibility and self-

control.

On the basis of these dimensions, Baumrind identified three parenting styles (summarized in Table 6.1).

| Communication | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Style | Warmth | Discipline | Expectations of Maturity | Parent to Child | Child to Parent |

| Authoritarian | Low | Strict, often physical | High | High | Low |

| Permissive | High | Rare | Low | Low | High |

| Authoritative | High | Moderate, with much discussion | Moderate | High | High |

authoritarian parenting

An approach to child rearing that is characterized by high behavioral standards, strict punishment of misconduct, and little communication from child to parent.

Authoritarian parenting. The authoritarian parent’s word is law, not to be questioned. Misconduct brings strict punishment, usually physical. Authoritarian parents set down clear rules and hold high standards. They do not expect children to offer opinions; discussion about emotions and expressions of affection are rare. One adult from authoritarian parents said that “How do you feel?” had only two possible answers: “Fine” and “Tired.”

permissive parenting

An approach to child rearing that is characterized by high nurturance and communication but little discipline, guidance, or control.

Permissive parenting. Permissive parents (also called indulgent) make few demands, hiding any impatience they feel. Discipline is lax, partly because they have low expectations for maturity. Permissive parents are nurturing and accepting, listening to whatever their offspring say, including cursing at the parent.

authoritative parenting

An approach to child rearing in which the parents set limits and enforce rules but are flexible and listen to their children.

Authoritative parenting. Authoritative parents set limits, but they are flexible. They encourage maturity, but they usually listen and forgive (not punish) if the child falls short. They consider themselves guides, not authorities (unlike authoritarian parents) and not friends (unlike permissive parents).

neglectful/uninvolved parenting

An approach to child rearing in which the parents seem indifferent toward their children, not knowing or caring about their children’s lives.

Other researchers describe a fourth style, called neglectful/uninvolved parenting. Neglectful parents are oblivious to their children’s behavior; they seem not to care. Their children do whatever they want, which makes some observers think the parents are permissive. But permissive parents care very much about their children, unlike neglectful parents.

The following long-

Authoritarian parents raise children who become conscientious, obedient, and quiet but not especially happy. Such children tend to feel guilty or depressed, internalizing their frustrations and blaming themselves when things don’t go well. As adolescents, they sometimes rebel, leaving home before age 20.

Permissive parents raise children who lack self-

control, especially in the give- and- take of peer relationships. Inadequate emotional regulation makes them immature and impedes friendships, so they are unhappy. They tend to continue to live at home, still dependent on their parents in adulthood. Authoritative parents raise children who are successful, articulate, happy with themselves, and generous with others. These children are usually liked by teachers and peers, especially in cultures that value individual initiative (e.g., the United States).

Neglectful/uninvolved parents raise children who are immature, sad, lonely, and at risk of injury and abuse, not only in early childhood but also lifelong.

PROBLEMS WITH THE RESEARCH Baumrind’s classification schema has been soundly criticized by more recent scientists. You can probably already see some of the ways her research was flawed.

She did not consider socioeconomic differences.

She was unaware of cultural differences.

She focused more on parent attitudes than on parent actions.

She overlooked children’s temperamental differences.

She did not recognize that some “authoritarian” parents are also affectionate.

She did not realize that some “permissive” parents provide extensive verbal guidance.

More recent research finds that a child’s temperament powerfully affects caregivers. Good caregivers treat each child as an individual who needs personalized care. For example, fearful children require reassurance, while impulsive ones need strong guidelines. Parents of such children may, to outsiders, seem permissive or authoritarian.

Overprotection may be a consequence, not a cause, of childhood anxiety (McShane & Hastings, 2009; Deater-

A study of parenting at age 2 and children’s competence in kindergarten (including emotional regulation and friendships) found “multiple developmental pathways,” with the best outcomes dependent on both the child and the adult (Blandon et al., 2010). Such studies suggest that simplistic advice—

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Culture and Parenting Style

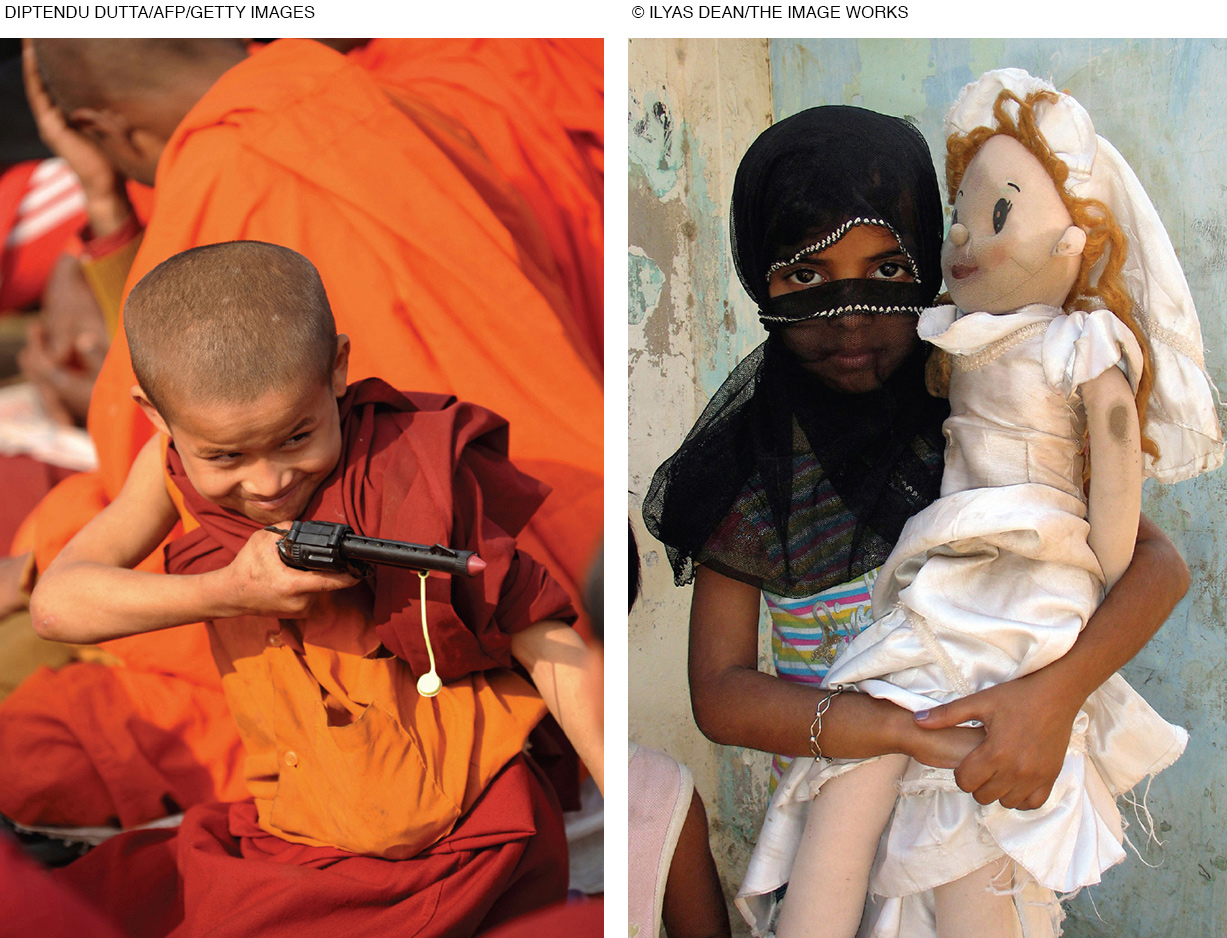

Culture powerfully affects caregiving style. This is obvious internationally. In some nations, parents are expected to beat their children; in other nations, parents are arrested if they punish their children physically. Some cultures advise parents to never praise their children; elsewhere parents often tell their children they are wonderful, even when they are not.

This difference is evident in multiethnic nations including the United States, where parents of Chinese, Caribbean, or African heritage are often stricter than those of European backgrounds. To the surprise of many researchers, the children of some ethnic minority families seem more likely to thrive with strict parents than with easygoing ones (Parke & Buriel, 2006; F. Ng et al., 2014).

A detailed study of Mexican American mothers of 4-

This simple strategy, with the mother asserting authority and the children obeying without question, might be considered authoritarian. Almost never, however, did the mothers use physical punishment or even harsh threats when the children did not immediately do as they were told—

Hailey [the 4-

[Livas-

Note that the mother’s first three efforts failed, and then a look accompanied by an explanation (albeit inaccurate in that setting, as no one could be hurt) succeeded. The researchers explain that these Mexican American families did not fit any of Baumrind’s categories; respect for adult authority did not mean an authoritarian relationship. Instead, the relationship shows evident carino (caring) (Livas-

Although cultural differences are apparent between majority and minority families in the United States, and between African American and Hispanic ethnic groups, we must not exaggerate those differences. Harsh, cold parenting seems harmful in every group, and parents of all groups usually show warmth to their children (Dyer et al., 2014).

Parental affection and warmth allow children to develop self-

Given a multi-

Becoming Boys or Girls: Sex and Gender

Another challenge for caregivers is raising a child with a healthy understanding of sex and gender. Biology determines whether a baby is male or female (except in very rare cases): Those XX or XY chromosomes normally shape organs and produce hormones that differ for males and females.

sex differences

Biological differences between males and females, in organs, hormones, and body shape.

gender differences

Differences in male and female roles, behaviors, clothes and so on that are prescribed by a culture.

Many scientists distinguish sex differences, which are biological, from gender differences, which are culturally prescribed. In theory, this distinction seems straightforward, but, as with every nature–

Although that 23rd pair of chromosomes is crucial, learning is evident, first in the blue or pink caps put on newborn heads, and soon in what the children learn. Before age 2, children use gender labels (Mrs., Mr., lady, man) consistently. By age 4, children are convinced that certain toys (such as dolls or trucks) and roles (Daddy, Mommy, nurse, teacher, police officer, soldier) are reserved for one sex or the other.

Young children often believe that sex differences are not inborn. One little girl said she would grow a penis when she got older, and one little boy offered to buy his mother one. A 3-

Many young children do not realize that their own sex is permanent. In one preschool, the children themselves decided that one wash-

Boy: This is for the boys.

Girl: Stop it. I’m not a girl and a boy, so I’m here.

Boy: What?

Girl: I’m a boy and also a girl.

Boy: You, now, are you today a boy?

Girl: Yes.

Boy: And tomorrow what will you be?

Girl: A girl. Tomorrow I’ll be a girl. Today I’ll be a boy.

Boy: And after tomorrow?

Girl: I’ll be a girl.

[Ehrlich & Blum-

Although they may not think of sex as biological, many preschoolers are quite rigid about gender roles. Despite their parents’ and teachers’ wishes, children say, “No girls [or boys] allowed.” Most children consider ethnic discrimination immoral, but they accept some sex discrimination (Møller & Tenenbaum, 2011). Why?

Theories about how and why this occurs suggest explanations (Martin & Ruble, 2010; Leaper, 2013). Consider five broad theories.

phallic stage

Freud’s third stage of development, when the penis becomes the focus of concern and pleasure.

PSYCHOANALYTIC THEORY Freud (1938/1995) called the period from about ages 3 to 6 the phallic stage, named after the phallus, the Greek word for penis. At age 3 or 4, said Freud, boys become aware of their male sexual organ. They masturbate, fear castration, and develop sexual feelings toward their mother.

Oedipus complex

The unconscious desire of young boys to replace their fathers and win their mothers’ exclusive love.

These feelings make every young boy jealous of his father—

superego

In psychoanalytic theory, the judgmental part of the personality that internalizes the moral standards of the parents.

Freud believed that this ancient story dramatizes the overwhelming emotions that all boys feel about their parents—

That marks the beginning of morality, according to psychoanalytic theory. This theory contends that a boy’s fascination with superheroes, guns, kung fu, and the like arises from his unconscious impulse to kill his father. Further, an adult man’s homosexuality, homophobia, or obsession with guns, prostitutes, and hell arises from problems at the phallic stage.

Freud offered several descriptions of the moral development of girls. He thought they also want to eliminate the same-

identification

Considering the behaviors, appearance and and attitudes of someone else to be one’s own.

According to this theory, at about age 5, children cope with guilt and fear about their strong impulses about their parents through identification; that is, they try to become like the same-

Most psychologists have rejected Freud’s theory regarding sex and gender. They favor one or another of many other theories to explain the young child’s sex and gender awareness. However, sometimes personal experience seems to confirm Freud.

A CASE TO STUDY

My Daughters

Freud’s theory suggests that parents should encourage children to follow gender roles. Many social scientists disagree. They contend that the psychoanalytic explanation of sexual and moral development “flies in the face of sociological and historical evidence” (David et al., 2004, p. 139).

I learned in graduate school that Freud was unscientific, and I deliberately dressed my baby girls in blue, not pink. However, developmental scientists seek to connect research, theory, and experience. My own experience has made me rethink my assumptions.

My rethinking began with a conversation with my eldest daughter, Bethany, when she was about 4 years old:

Bethany: When I grow up, I’m going to marry Daddy.

Me: But Daddy’s married to me.

Bethany: That’s all right. When I grow up, you’ll probably be dead.

Me: [Determined to stick up for myself] Daddy’s older than me, so when I’m dead, he’ll probably be dead, too.

Bethany: That’s OK. I’ll marry him when he gets born again.

I was dumbfounded, without a good reply. I had no idea where she had gotten the concept of reincarnation. Bethany saw my face fall, and she took pity on me:

Bethany: Don’t worry, Mommy. After you get born again, you can be our baby.

The second episode was a conversation I had with Rachel when she was about 5:

Rachel: When I get married, I’m going to marry Daddy.

Me: Daddy’s already married to me.

Rachel: [With the joy of having discovered a wonderful solution] Then we can have a double wedding!

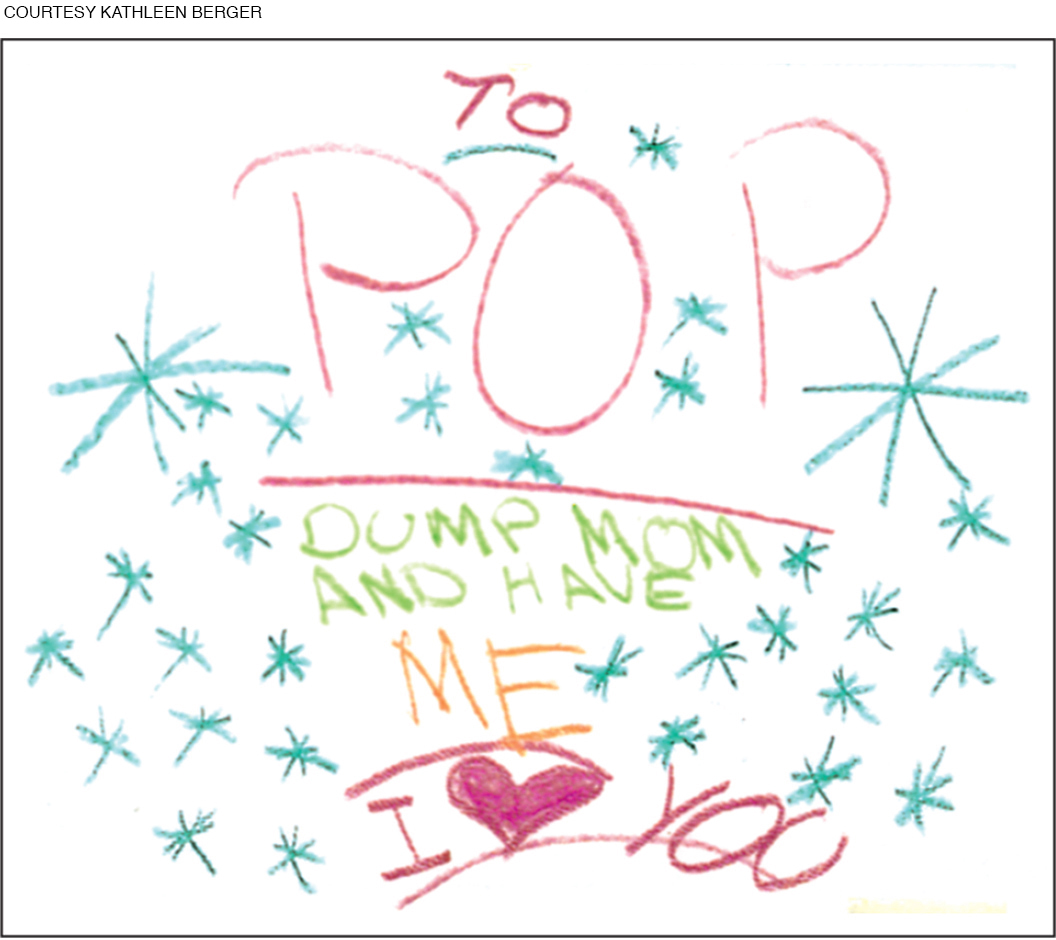

The third episode was considerably more graphic. It took the form of a “Valentine” left on my husband’s pillow on February 14th by my daughter Elissa (see Figure 6.2).

Finally, when Sarah turned 5, she also said she would marry her father. I told her she couldn’t, because he was married to me. Her response revealed one more hazard of watching TV: “Oh, yes, a man can have two wives. I saw it on television.”

As you remember from Chapter 1, a single example (or four daughters from one family) does not prove that Freud was correct. I still think Freud was wrong on many counts. But his description of the phallic stage seems less bizarre than I once thought.

BEHAVIORISM Behaviorists believe that virtually all roles, values, and morals are learned. To behaviorists, gender distinctions are the product of ongoing reinforcement and punishment, as well as social learning.

For example, a boy who asks for both a train and a doll for his birthday is likely to get the train. Boys are rewarded for boyish requests, not for girlish ones. Indeed, the parental push toward traditional gender behavior in play and chores is among the most robust findings of decades of research on this topic (Eagly & Wood, 2013).

Gender differentiation may be subtle, with parents unaware that they are reinforcing traditional masculine or feminine behavior. For example, a study of parents talking to young children found that numbers were mentioned more often with the boys (Chang et al., 2011). This may be a precursor to the boys becoming more interested in math and science later on.

Social learning is considered an extension of behaviorism. According to that theory, people model themselves after people they perceive to be nurturing, powerful, and yet similar to themselves. For young children, those people are usually their parents.

As it happens, adults are the most gender-

Furthermore, although national policies (e.g., subsidizing early education) impact gender roles and many fathers are involved caregivers, women in every nation do much more child care, house cleaning, and meal preparation than do men (Hook, 2010). Children follow those examples, unaware that the behavior they see is caused partly by their very existence: Before children are born, many couples share domestic work equally.

Everywhere young girls and boys are socialized differently. For example, two 4-

gender schema

A child’s cognitive concept or general belief about male and female differences.

COGNITIVE THEORY Cognitive theory offers an alternative explanation for the strong gender identity that becomes apparent at about age 5 (Kohlberg et al., 1983). Remember that cognitive theorists focus on how children understand various ideas. One idea that children develop is the difference between the sexes. A gender schema is the child’s understanding of male–

As cognitive theorists point out, young children see many gender-

During the preoperational stage, appearance trumps logic. One group of researchers who endorse the cognitive interpretation note that “young children pass through a stage of gender appearance rigidity; girls insist on wearing dresses, often pink and frilly, whereas boys refuse to wear anything with a hint of femininity” (Halim et al., 2014, p. 1091).

In research reported by this group, parents discouraged stereotypes, but that did not necessarily sway a preschool girl who wanted a bright pink tutu and a sparkly tiara. The child’s gender schema overcame experiences with parents who avoided rigid gender stereotypes.

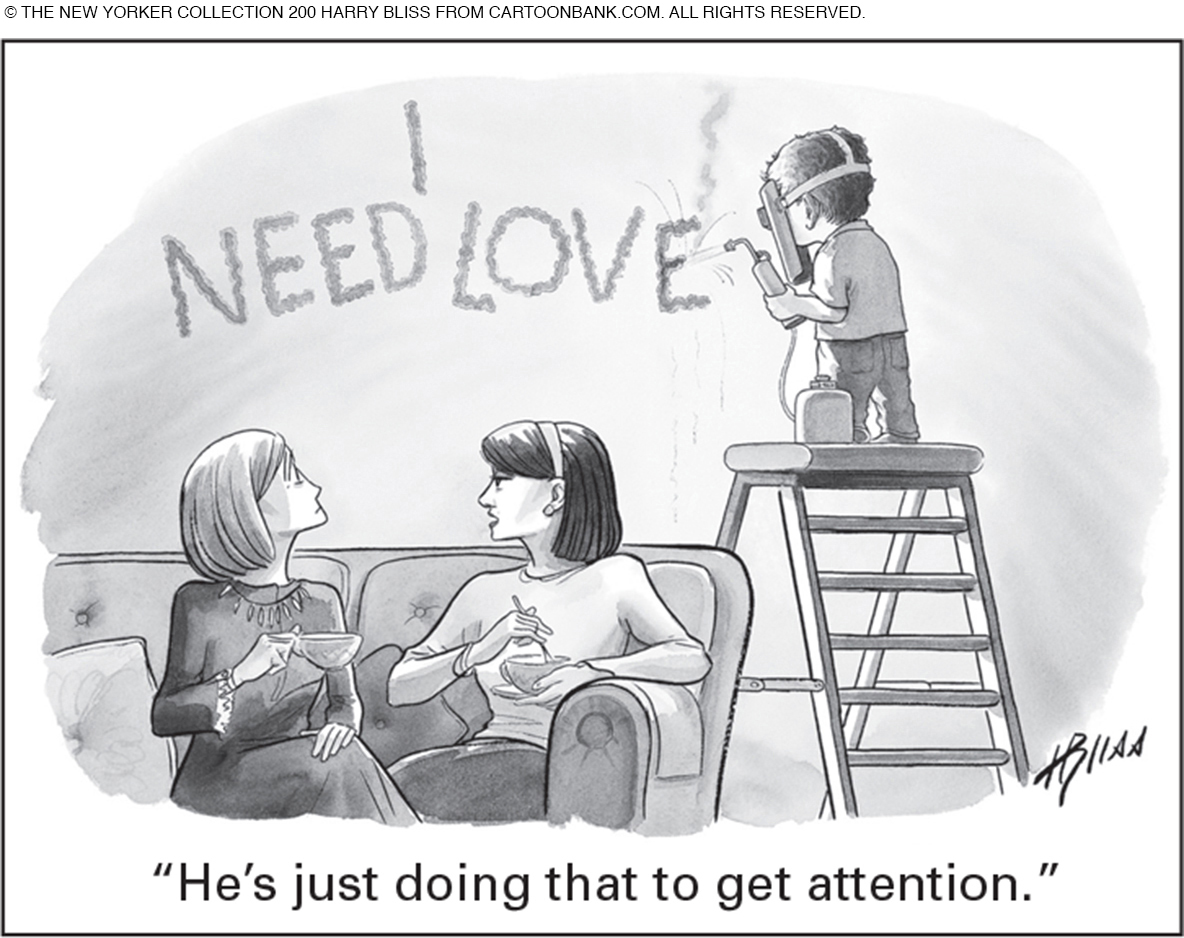

HUMANISM Humanism stresses the hierarchy of needs, beginning with survival, then safety, then love and belonging. The final two needs—

Ideally, babies have all their basic needs (level one) met, and toddlers learn to feel safe (level two). That makes love and belonging (level three) crucial during early childhood, when children seek acceptance from their peers. Therefore, the girls seek to be one of the girls and the boys to be one of the boys.

In a study of slightly older children, participants wanted to be part of same-

On her first day of school, Mia sits at the lunch table eating a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. She notices that a few boys are eating peanut butter and jelly, but not one girl is. When her father picks her up from school, Mia runs up to him and exclaims, “Peanut butter and jelly is for boys! I want a turkey sandwich tomorrow.”

[Quoted in Miller et al., 2013, p. 307]

Humanism might interpret this as evidence that Mia’s need to belong to the girls in her class overruled her earlier basic hunger need, which was satisfied with peanut butter and jelly.

EVOLUTIONARY THEORY Evolutionary theory holds that male–

Already in early childhood, children have a powerful urge to become like the men, or like the women. This will prepare them, later on, to mate and conceive a new generation, following a deep evolutionary drive.

Thus, according to this theory, over millennia of human history, genes, chromosomes, and hormones have evolved to allow the species to survive. Genes dictate that boys are more active (rough-

THINK CRITICALLY: Should children be encouraged to combine both male and female characteristics (called androgyny) or is learning male and female roles crucial for becoming a happy man or woman?

WHAT IS BEST? Each major developmental theory strives to explain the ideas that young children express and the roles they follow. No consensus has been reached. That challenges caregivers, because they know they should not blindly follow the norms of their culture, yet they also know they need to provide guidance regarding male–

Regarding sex or gender, those who contend that nature (sex) is more important than nurture tend to design, cite, and believe studies that endorse their perspective. That has been equally true for those who believe that nurture (gender) is more important than nature. Only recently has a true interactionist perspective, emphasizing how nature affects nurture and vice versa, been endorsed (Eagly & Wood, 2013).

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 6.12

1. Describe the characteristics of the parenting style that seems to promote the happiest, most successful children.

Authoritative parents produce the happiest, most successful children. These parents set limits but are still flexible. They encourage maturity, but they usually listen and give consequences if the child falls short. They consider themselves guides; they are not authorities and not friends.

Question 6.13

2. What are the limitations of Baumrind’s description of parenting styles?

Recent scientists have criticized Baumrind’s classification schema. Some of their reasons include: (1) She did not consider socioeconomic differences; (2) she was unaware of cultural differences; (3) she focused more on parent attitudes than on parent actions; (4) she overlooked children’s temperamental differences; (5) she did not recognize that some “authoritarian” parents are also affectionate; and (6) she did not realize that some “permissive” parents provide extensive verbal guidance.

Question 6.14

3. What seems to be the worst parenting style?

Neglectful/uninvolved seems to be the worst parenting style. These parents raise children who are immature, sad, lonely, and at risk of injury and abuse, not only in early childhood but also throughout their lives.

Question 6.15

4. How does culture affect parenting style?

Culture affects caregiving style in a powerful way. In some nations, parents are expected to beat their children; in other nations, those actions are illegal. Some cultures advise parents to never praise their children; elsewhere, parents often tell their children they are wonderful, even when they are not. However, across all groups, parents usually show warmth to their children; harsh, cold parenting is likely harmful.

Question 6.16

5. How does a child’s temperament interact with parenting style?

Recent research finds that a child’s temperament powerfully affects caregivers. For example, fearful children require reassurance, while impulsive ones need strong guidelines. Parents of such children may, to outsiders, seem permissive or authoritarian. Good caregivers treat each child as an individual who needs personalized care.

Question 6.17

6. What does psychoanalytic theory say about the origins of sex differences and gender roles?

According to psychoanalytic theory, at the phallic stage children cope with guilt and fear through identification; that is, they try to become like the same-

Question 6.18

7. What do behaviorists say about the origins of sex differences and gender roles?

Behaviorists believe that all roles are learned through ongoing reinforcement, punishment, and social learning. They suggest that authority figures reward gender-

Question 6.19

8. How does preoperational thought lead to sexism?

Although they may not think of sex as biological, many preschoolers are quite rigid about gender roles. By age 4, children are convinced that certain toys and roles are reserved for one sex or the other. According to research, even when parents discouraged stereotypes, their children’s gender schemas won out.

Question 6.20

9. What are the advantages and disadvantages of encouraging children to be unisex?

Caregivers know they should not blindly follow the norms of their culture, yet they also know they need to provide guidance regarding male-