A Healthy Time

middle childhood

The period between early childhood and early adolescence, approximately from ages 6 to 11.

Genes and environment usually safeguard middle childhood, as the years from about 6 to 11 are called (Konner, 2010). Fatal diseases and accidents are rare; nature and nurture make these the healthiest years of life. In the United States in 2010, the death rate for 5-

Genetic diseases are more threatening in early infancy or old age, infectious diseases are kept away via immunization, and fatal accidents—

The already-

Oral health has improved, with more brushing and fluoride. A survey found that 75 percent of U.S. children saw a dentist for preventive care in the past year, and for 70 percent of them, the condition of their teeth was very good (Iida & Rozier, 2013).

Children’s Health Habits

In marked contrast to infancy or adolescence, middle childhood is a time of slow and steady growth, a little more than 2 inches and 5 pounds a year (more than 5 centimeters and 2 kilograms). Children can maintain good health if adults teach them how, providing regular medical care. This is crucial, because those who have inadequate health care in childhood tend to have poor health in adulthood, even if their circumstances improve (Miller & Chen, 2010; Blair & Raver, 2012).

Camps for children with asthma, cancer, diabetes, sickle-

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY Beyond the sheer fun of playing, the benefits of physical activity—

A new concept in psychology is embodied cognition, the idea that human thoughts are affected by body health, comfort, position, and so on. This suggests that children learn by doing and that an active body promotes learning (Pouw et al., 2014).

Sports are not always beneficial. Organizations have developed guidelines to prevent concussions among 7-

WHERE TO EXERCISE Children reap the benefits of exercise in their neighborhoods, schools, and sports leagues. However, finding a place to play is much more difficult than it was.

Neighborhood play was once a daily event. Rules and boundaries were adapted to the context (out of bounds was “past the tree” or “behind the parked truck”). Stickball, touch football, tag, hide-

Children play tag, hide and seek, or pickup basketball. They compete with one another but always according to rules, and rules that they enforce themselves without recourse to an impartial judge. The penalty for not playing by the rules is not playing, that is, social exclusion.

[Gillespie, 2010, p. 298]

For school-

Unfortunately, modern life undercuts neighborhood play. Vacant lots and empty fields have disappeared, and parents fear “stranger danger”—thinking that a stranger will hurt their child (which is exceedingly rare) and ignoring the many benefits of outside play. As one advocate of unsupervised, creative childhood play sadly notes:

Actions that would have been considered paranoid in the ’70s—

[Rosin, 2014]

Indoor activities (homework, screen time) crowd out outdoor play. Parents used to tell their children “go out and play”; now they say “stay inside.” Some parents enroll their children in organized sports—

As a result, the children most likely to benefit are least likely to engage, even when enrollment is free. The reasons are many, the consequences sad (Dearing et al., 2009). Another group unlikely to participate are older girls, again a group particularly likely to benefit from athletic activity (Kremer et al., 2014).

Active play in school is a logical alternative. However, in the United States, currently schools and teachers are judged by test scores, which shrinks time for physical education and recess. A study of Texas elementary schools found that 24 percent had no recess at all and only 1 percent had recess several times a day (W. Zhu et al., 2010).

Texas is no exception. A survey asking teachers of 10,000 third-

These researchers write that “many children from disadvantaged backgrounds are not free to roam their neighborhoods or even their own yards unless they are accompanied by adults. For many of these children, recess periods may be the only opportunity for them to practice their social skills with other children” (Barros et al., 2009, p. 434).

Even when schools mandate gym, classes may be too full for active play, or requirements may be ignored. For instance, although Alabama requires 30 minutes of physical education daily in primary schools, the average in one district was only 22 minutes. No school in that district had recess or after-

THINK CRITICALLY: Do you agree with Japan or the United States regarding physical activity in school? Why?

Ironically, schools in Japan, where many children score well on international tests, usually have five or more recess breaks totaling more than an hour each day, in addition to gym classes. Japanese public schools often are well-

Health Problems in Middle Childhood

Some chronic health conditions, including Tourette syndrome, stuttering, and allergies, may worsen during the school years. Even minor problems—

childhood overweight

In a child, having a BMI above the 85th percentile, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control’s 1980 standards for children of a given age.

childhood obesity

In a child, having a BMI above the 95th percentile, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control’s 1980 standards for children of a given age.

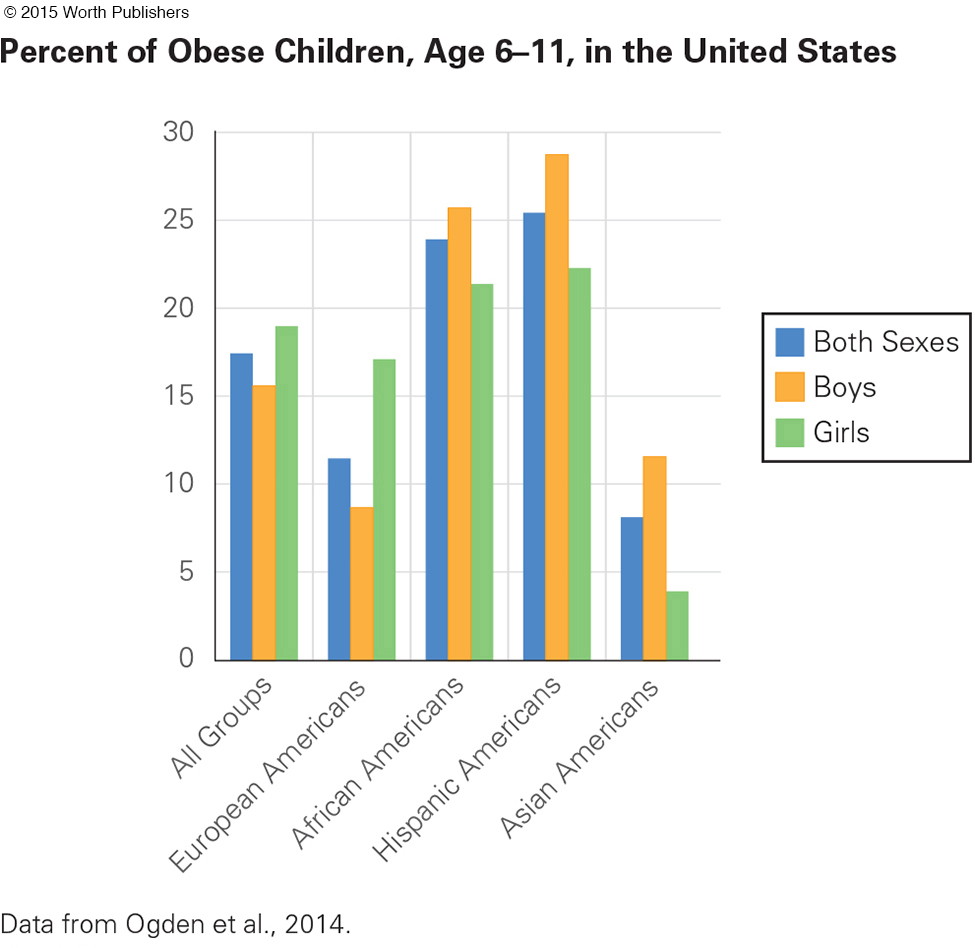

CHILDHOOD OBESITY Body mass index (BMI) reflects the ratio of weight to height. Childhood overweight is usually defined as a BMI above the 85th percentile for children at that age, and childhood obesity is defined as a BMI above the 95th percentile. Those percentiles were set decades ago, when fewer children were overweight. In 2012, 18 percent of 6-

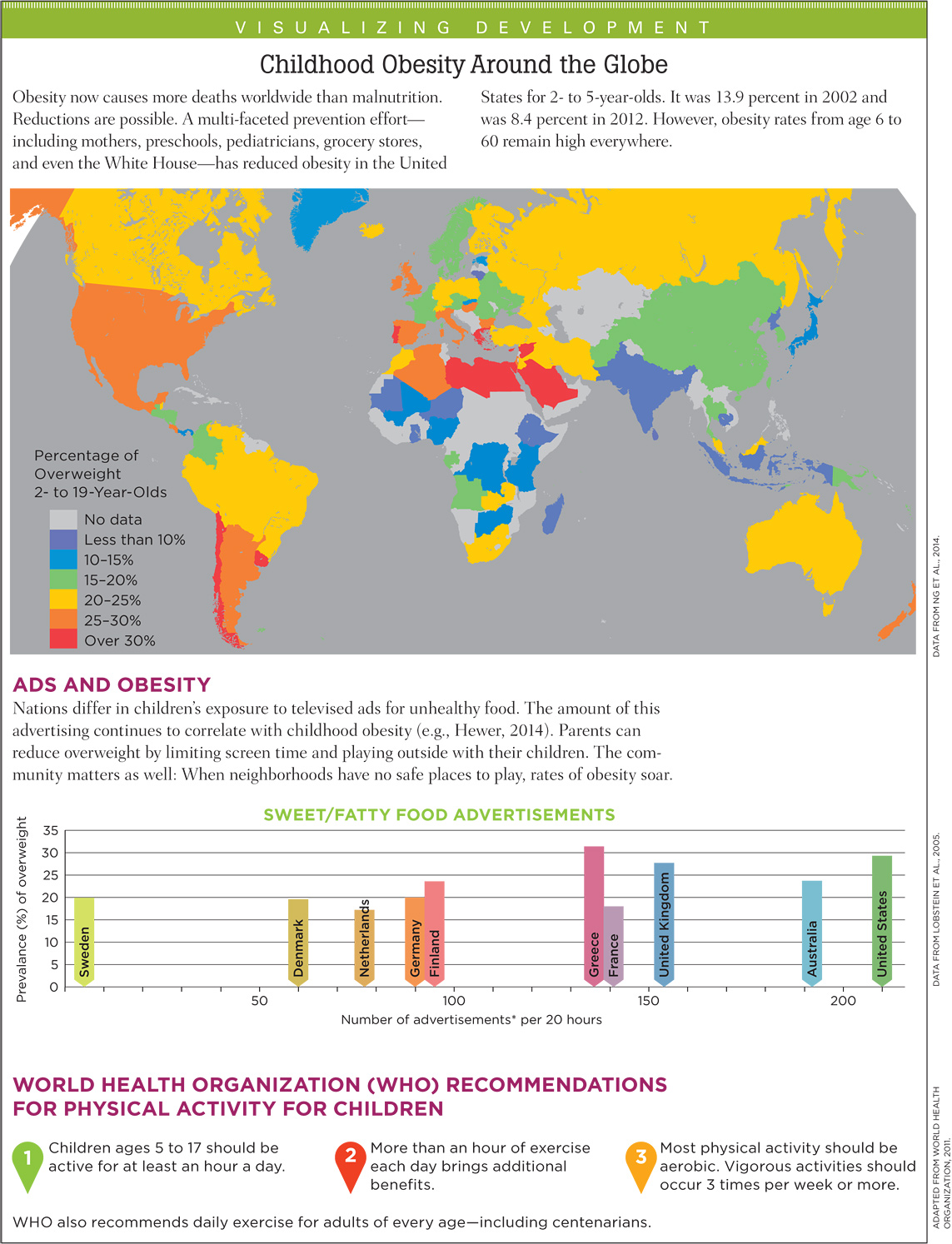

Childhood obesity has more than doubled since 1980 in all three nations of North America (Ogden et al., 2011). Since 2000, U.S. rates have leveled off, even declining in preschool children, but increases continue in most other nations, including the most populous two, China and India (Gupta et al., 2012; Ji et al., 2013). A group of Chinese scholars concluded: “The prognosis for China’s childhood-

There are “hundreds if not thousands of contributing factors” for childhood obesity, from the cells of the body to the norms of the society (Harrison et al., 2011, p. 51). Dozens of genes affect weight by influencing activity level, hunger, food preferences, body type, and metabolism. New genes and alleles that affect obesity—

Knowing that genes are involved may slow down the impulse to blame people for being overweight. However, genes do not explain the marked increases in obesity, since genes change little over the generations (Harrison et al., 2011).

Look at the figure on obesity among 6-

Question 7.1

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Are boys more likely to be overweight than girls?

Overall, no. But in some groups, yes. Rates of obesity among Asian American boys are almost three times higher than Asian American girls.

Before answering, consider gender: European American girls are twice as likely to be obese as boys, but in the other groups boys are more often obese than girls. Ethnic differences in childhood obesity almost disappeared in a study that controlled for family income and early parenting (Taveras et al., 2013). Therefore, genes are not the primary culprit for overweight children.

What parenting practices make children too heavy? Obesity rates rise if:

Infants are not breast-

fed and if they are fed solid foods before 4 months Preschoolers watch TV in their bedrooms and drink soda

School-

age children have insufficient sleep, extensive screen time, and little active play

(Hart et al., 2011; Taveras et al., 2013)

Children themselves have pester power—the power to make adults do what they want (Powell et al., 2011). They pester parents to buy foods advertised on television. Attempts to limit sugar and fat clash with the financial goals of many corporations, whose advertising and packaging of calorie-

On the plus side, many schools have policies that foster good nutrition. A national survey in the United States found that schools are reducing all types of commercial food advertising. Nonetheless, vending machines are prevalent in high schools, and free fast-

Simply offering healthy food is not enough to convince children to change their habits; context and culture are crucial (Hanks et al., 2013). Communities can build parks, bike paths, and sidewalks, and nations can decrease subsidies for sugar and corn.

Immigrants who want to “eat American” may not be aware of the correlation between fast food consumption and childhood obesity (Alviola et al., 2013). In North America and Europe, those who immigrated as adults are less often obese than the native-

asthma

A chronic disease of the respiratory system in which inflammation narrows the airways from the nose and mouth to the lungs, causing difficulty in breathing. Signs and symptoms include wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and coughing.

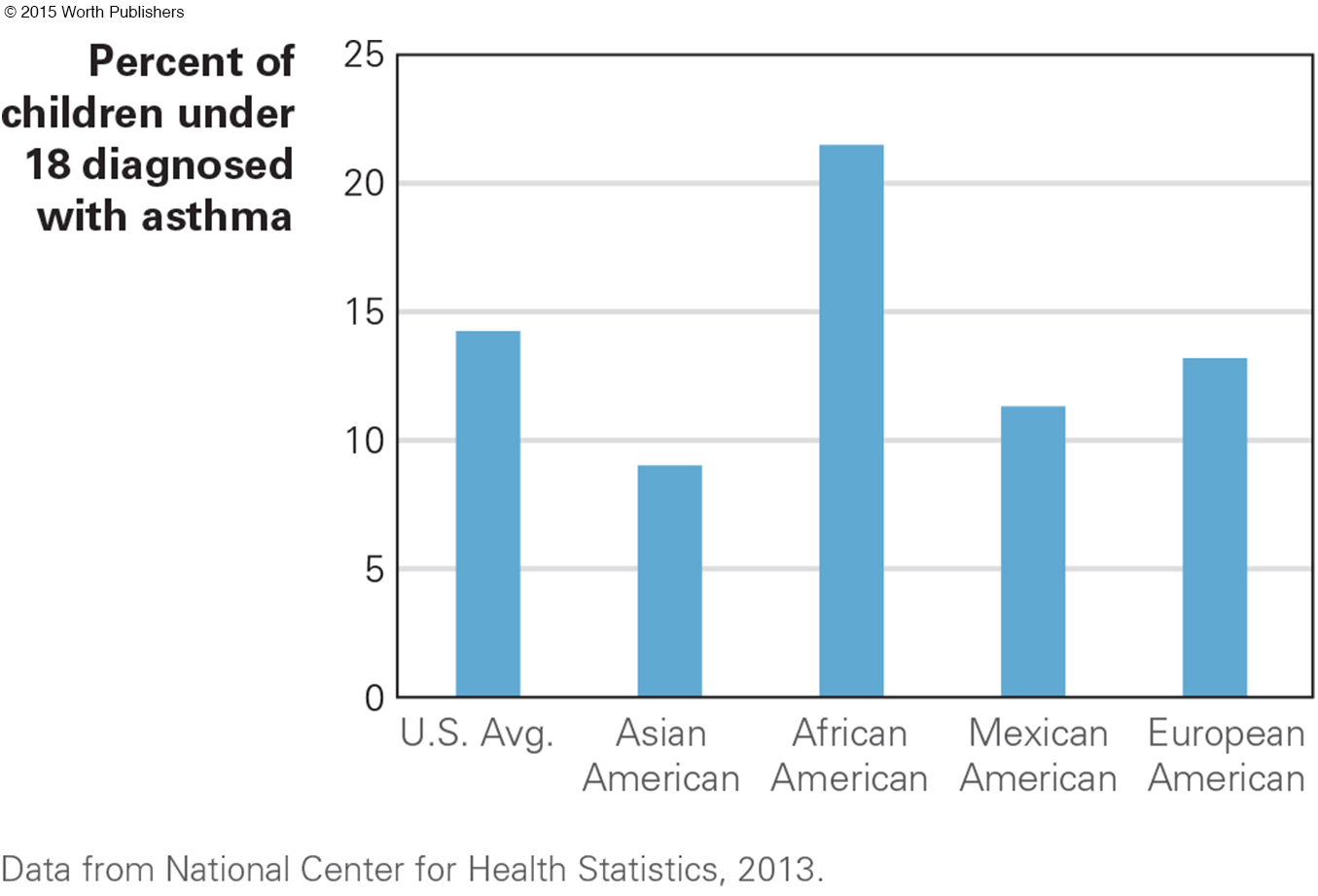

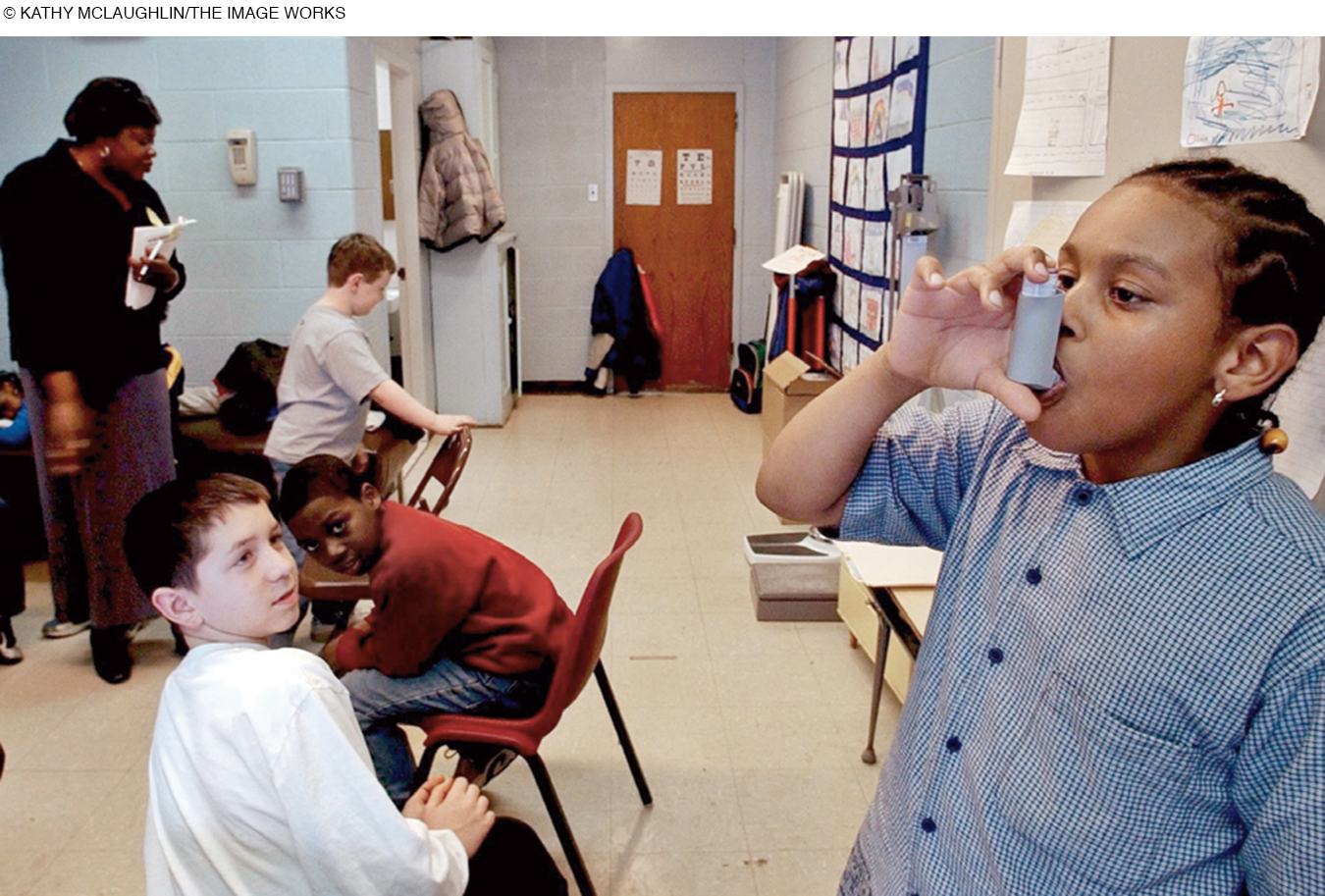

ASTHMA Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways that makes breathing difficult. Sufferers have periodic attacks, sometimes rushing to the hospital emergency room.

In the United States, childhood asthma rates have tripled since 1980 (see Figure 7.2). Parents report that 15 percent of U.S. 5-

Researchers have long sought the causes of asthma. Some alleles are contributors, although none acts alone. Several aspects of modern life—

Some experts suggest a hygiene hypothesis: that “the immune system needs to tangle with microbes when we are young” (Leslie, 2012, p. 1428). Children may be overprotected from viruses and bacteria. In their concern about hygiene, parents prevent exposure to minor infections, diseases, and family pets that would strengthen their child’s immunity.

This hypothesis is supported by data showing that (1) first-

Perhaps. However, there are “many paths to asthma,” with no one cause identified as crucial (H. Kim et al., 2010). As a reviewer of the hygiene hypothesis notes, “the picture can be dishearteningly complicated” (Couzin-

Fortunately, many factors can reduce asthma. One study began by acknowledging that exertion sometimes triggers an asthma attack, but then it examined programs that advance physical fitness in children with asthma. The conclusion: Exercise helps reduce attacks, as long as it is tailored to the particular needs of the child (Wanrooij et al., 2014).

Parents of children with asthma can do their part. In one study, 133 Latino caregivers—

Three months later, one-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 7.2

1. How does growth during middle childhood compare with growth earlier or later?

In marked contrast to infancy or adolescence, middle childhood is a time of slow and steady growth, a little more than two inches and five pounds a year.

Question 7.3

2. Why is middle childhood considered a healthy time?

During middle childhood, fatal diseases and accidents are rare; nature and nurture make these the healthiest years of life. Genetic diseases are more threatening in early infancy or old age, infectious diseases are kept away via immunization, and fatal accidents—

Question 7.4

3. How does physical activity affect the child’s education?

Exercise improves academic achievement, with direct benefits of better cerebral blood flow and more neurotransmitters and indirect benefits of better mood and energy. The concept of embodied cognition suggests that children learn by doing and that an active body promotes learning.

Question 7.5

4. What are several reasons some children are less active than they should be?

Especially in the United States, children less often play outside in yards, vacant lots, and empty fields, which are less prevalent than in past generations. Parents also fear “stranger danger,” thinking that a stranger will hurt their child (which is exceedingly rare) and ignoring the many benefits of outside play. Indoor activities (homework, screen time) also crowd out outdoor play.

Question 7.6

5. What suggests that obesity is caused more by culture than genetics?

Childhood obesity has more than doubled since 1980 in all three nations of North America. Genes, however, do not explain these marked increases, because genes change little over the generations.

Question 7.7

6. What are the short-

As excessive weight builds, future health risks increase, average achievement decreases, self-

Question 7.8

7. Why is asthma more common now than it was?

A combination of sensitivity to allergens, early respiratory infections, and compromised lung function increases wheezing and shortness of breath, making asthma more likely. Some experts suggest a hygiene hypothesis: that children may be overprotected from viruses and bacteria. In their concern about hygiene, parents prevent exposure to minor infections, diseases, and pets that potentially could strengthen their child’s immunity.