Teaching and Learning

As we have seen, middle childhood is a time of great learning. Children worldwide learn whatever adults in their culture teach, and their brains are ready. Traditionally, they were educated at home, but now more than 95 percent of the world’s 7-

A foundation of this is language, with many young children learning two or more languages and almost all mastering several codes. Therefore, to understand education, we begin with language and then focus directly on school.

Language

As you remember, by age 6, children already know the basic vocabulary and grammar of their first language. Many also speak a second language fluently. These linguistic abilities allow the formation of a strong knowledge base, enabling children in middle childhood to learn thousands of new words and to apply complex grammar rules. Here are some specifics.

VOCABULARY As Piaget stressed, in middle childhood thinking becomes more flexible and logical. This allows children to understand prefixes, suffixes, compound words, phrases, and metaphors. For example, 2-

Metaphors, jokes, and puns are finally comprehended. Some jokes (“What is black and white and read all over?” “Why did the chicken cross the road?”) are funny only during middle childhood. Younger children don’t understand why anyone would laugh at them and teenagers find them lame and stale, but 6-

Indeed, a lack of metaphorical understanding, even if a child has a large vocabulary, signifies cognitive problems (Thomas et al., 2010). Humor is a diagnostic tool; a child who takes a joke too literally may have difficulty with social interaction.

Metaphors are context-

An American who lives in China noted phrases that U.S. children learn but that children in cultures without baseball do not, including “dropped the ball,” “on the ball,” “play ball,” “throw a curve,” “strike out” (Davis, 1999). If a teacher says “keep your eyes on the ball,” some immigrant children might not pay attention because they are looking for that ball.

CODE-

Shy 6-

Mastery of pragmatics allows children to change styles of speech, or “linguistic codes,” depending on their audience. Each code includes many aspects of language—

Sometimes the switch is between formal code (used in academic contexts) and informal code (used with friends); sometimes it is between standard (or proper) speech and dialect or slang (used on the street). Code in texting—

Some children do not know that slang, curses, and even contractions are not used in formal language. Everyone needs some language instruction because the logic of grammar (who or whom?) and of spelling (you) is impossible to deduce. Peers use the informal code; local communities transmit dialect, metaphors, and pronunciation; schools teach the formal code.

BILINGUAL EDUCATION Every nation includes many bilingual children; few of the world’s 6,000 languages are school languages. For instance, English is the language of instruction in Australia, but 17 percent of the children speak one of 246 other languages at home (Centre for Community Child Health & Telethon Institute for Child Health Research, 2009).

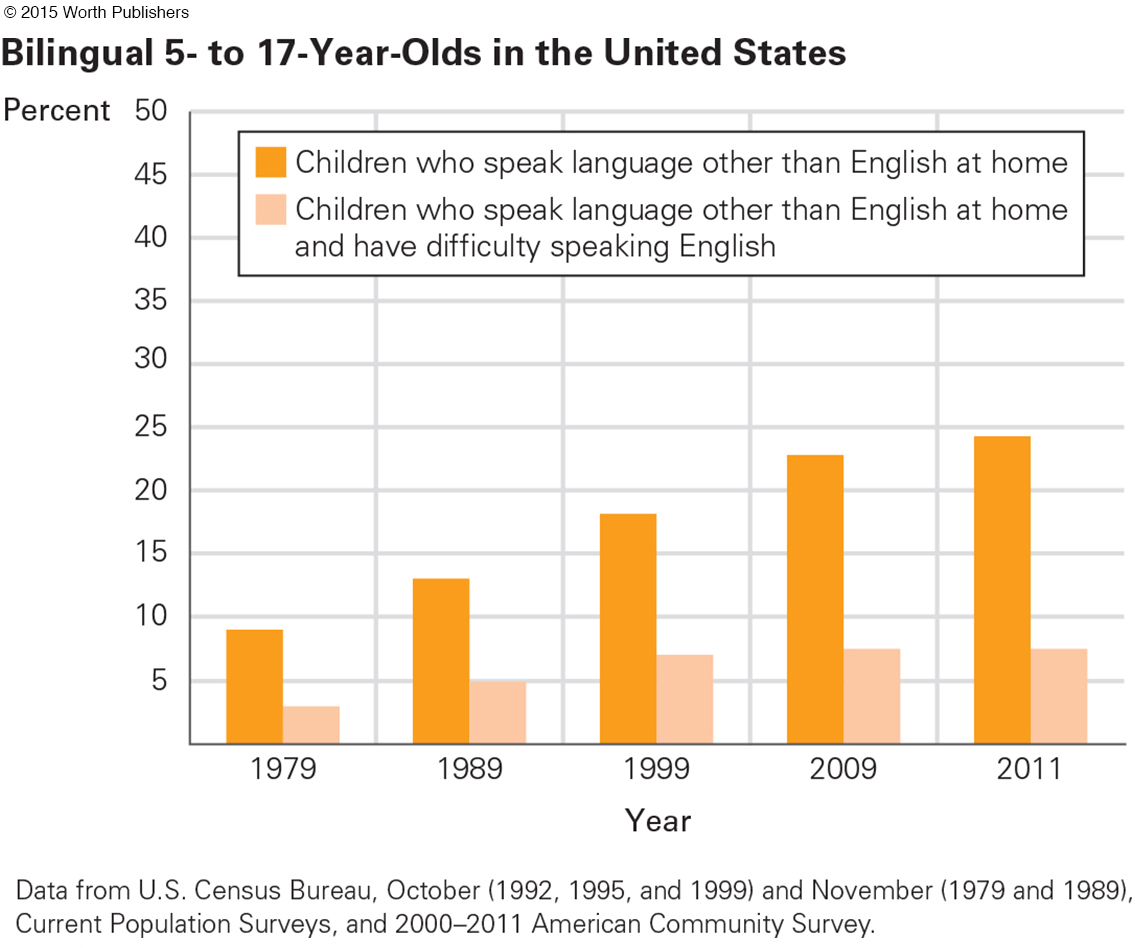

In the United States, almost 1 school-

If a child learns one language and then masters a second language, the brain adjusts. A study found no brain differences between monolingual children and bilingual children who spoke both languages from the first years of life.

However, from about age 4 through adolescence, the older children are when they learn a second language, the more likely their brains develop more cortical thickness on the left side (the language side) (Klein et al., 2014). This reflects what we know about language: School-

ELLs (English Language Learners)

Children in the United States whose proficiency in English is low—

In the United States, some children of every ethnicity are called ELLs, or English Language Learners, based on their ability to speak, write, and read English. Age, schooling, and SES all have an effect, but even high-

immersion

A strategy in which instruction in all school subjects occurs in the second (usually the majority) language that a child is learning.

bilingual education

A strategy in which school subjects are taught in both the learner’s original language and the second (majority) language.

ESL (English as a second language)

An approach to teaching English in which all children who do not speak English are placed together in an intensive course to learn basic English so that they can be educated with native English speakers.

Methods for teaching children the majority language range from immersion, in which instruction occurs entirely in the new language, to the opposite, in which children are taught in their first language until the second language can be taught as a “foreign” tongue (a rare strategy in the United States but common elsewhere). Between these extremes in the United States lies bilingual education, with instruction in two languages, and ESL (English as a second language), with all non-

Each of these methods sometimes succeeds and sometimes fails. The research is not yet clear as to which approach is best at what age, although vast differences are apparent from one nation to another (Mehisto & Genesee, 2015). The success of any method is affected by the literacy of the home environment (frequent reading, writing, and listening in any language helps); the warmth, training, and skill of the teacher; and the national context.

THINK CRITICALLY: Do you think English-

In the United States, in the twenty-

International Schooling

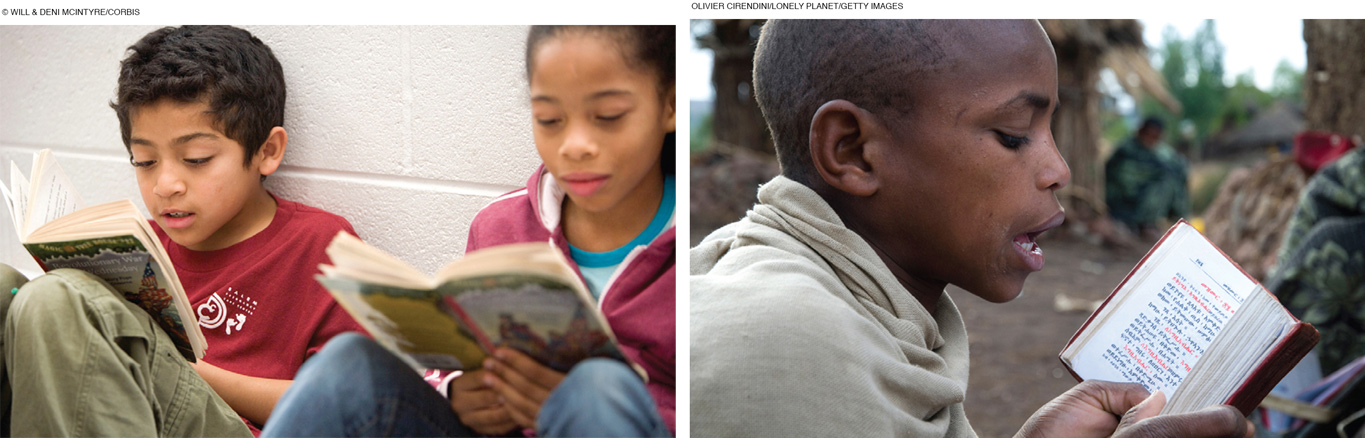

Everywhere, children are taught to read, write, and do arithmetic. Because of brain maturation and sequenced learning, 6-

| Math | |

|---|---|

| Age | Norms and Expectations |

|

4– |

|

| 6 years |

|

| 8 years |

|

| 10 years |

|

| 12 years |

|

| Math learning depends heavily on direct instruction and repeated practice, which means that some children advance more quickly than others. This list is only a rough guide, meant to illustrate the importance of sequence. | |

| Reading | |

|---|---|

| Age | Norms and Expectations |

|

4– |

|

|

6– |

|

| 8 years |

|

|

9– |

|

| 11– |

|

| 13+ years |

|

| Reading is a complex mix of skills, dependent on brain maturation, education, and culture. The sequence given here is approximate; it should not be taken as a standard to measure any particular child. | |

DIFFERENCES BY NATION Although literacy and numeracy (reading and math, respectively) and educated workers are valued everywhere, curricula vary by nation, by community, and by school. These variations are evident in the results of international tests, in the mix of school subjects, and in the relative power of parents, educators, and political leaders.

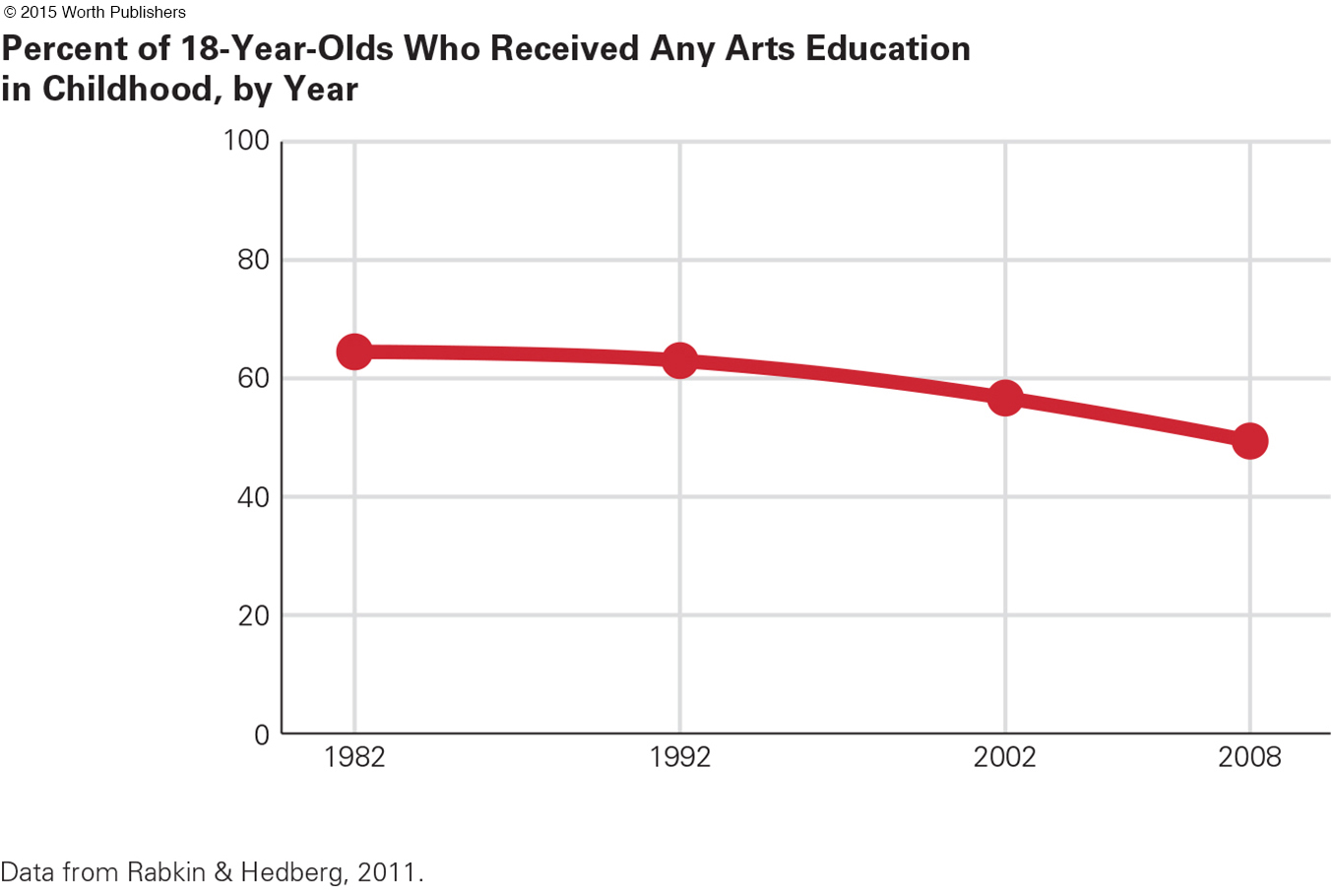

Geography, music, and art are essential in some places, not in others. Half of all U.S. 18-

Educational practices differ even between nations that are geographically and culturally close, and from one region to another within nations. For example in Canada, children in the province of Quebec study science about half as much as those in Ontario (50 compared to 92 hours per year) (Snyder & Dillow, 2013).

hidden curriculum

The unofficial, unstated, or implicit rules and priorities that influence the academic curriculum and every other aspect of learning in a school.

International variations are vast in the hidden curriculum, which includes all the implicit values and assumptions evident is course offerings, schedules, tracking, teacher characteristics, discipline, teaching methods, sports competition, student government, extracurricular activities, and so on.

Question 7.20

OBSERVATION QUIZ

What three differences do you see between recess in New York City (left) and Santa Rosa, California (right)?

The most obvious is the play equipment, but there are two others that make some New York children eager for recess to end. Did you notice the concrete play surface and the winter jackets?

In the United States, the hidden curriculum is thought to be the underlying reason for a disheartening difference in how students respond if teachers offer special assistance. In one study, middle-

THINK CRITICALLY: What is the hidden curriculum at your college or university?

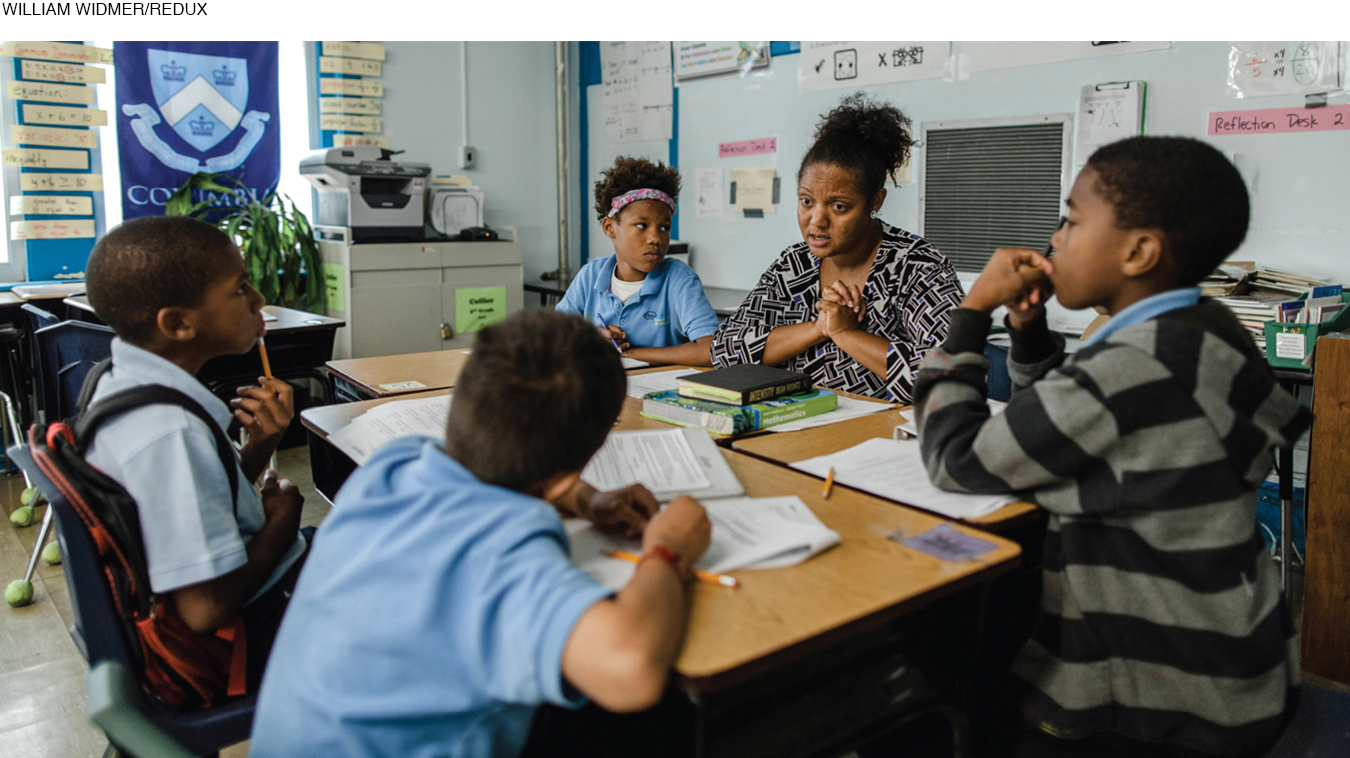

More generally, if teachers’ gender, ethnicity, or economic background is unlike that of the students, children may conclude that education is irrelevant for them. If the school has gifted classes, or if a charter school co-

Trends in Math and Science Study (TIMSS)

An international assessment of the math and science skills of fourth-

Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS)

Inaugurated in 2001, a planned five-

INTERNATIONAL TESTING Over the past two decades, more than 50 nations have participated in at least one massive international test of educational achievement. Science and math achievement are measured by Trends in Math and Science Study (TIMSS). The main test of reading is the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS). These tests have been given every few years since 1995, with East Asian nations ranking at the top.

Elaborate and extensive measures are in place to make the PIRLS and the TIMSS valid. For instance, test items are designed to be fair and culture-

The tests are far from perfect, however. Designing test items that are equally challenging to every student in every nation is impossible. Should fourth-

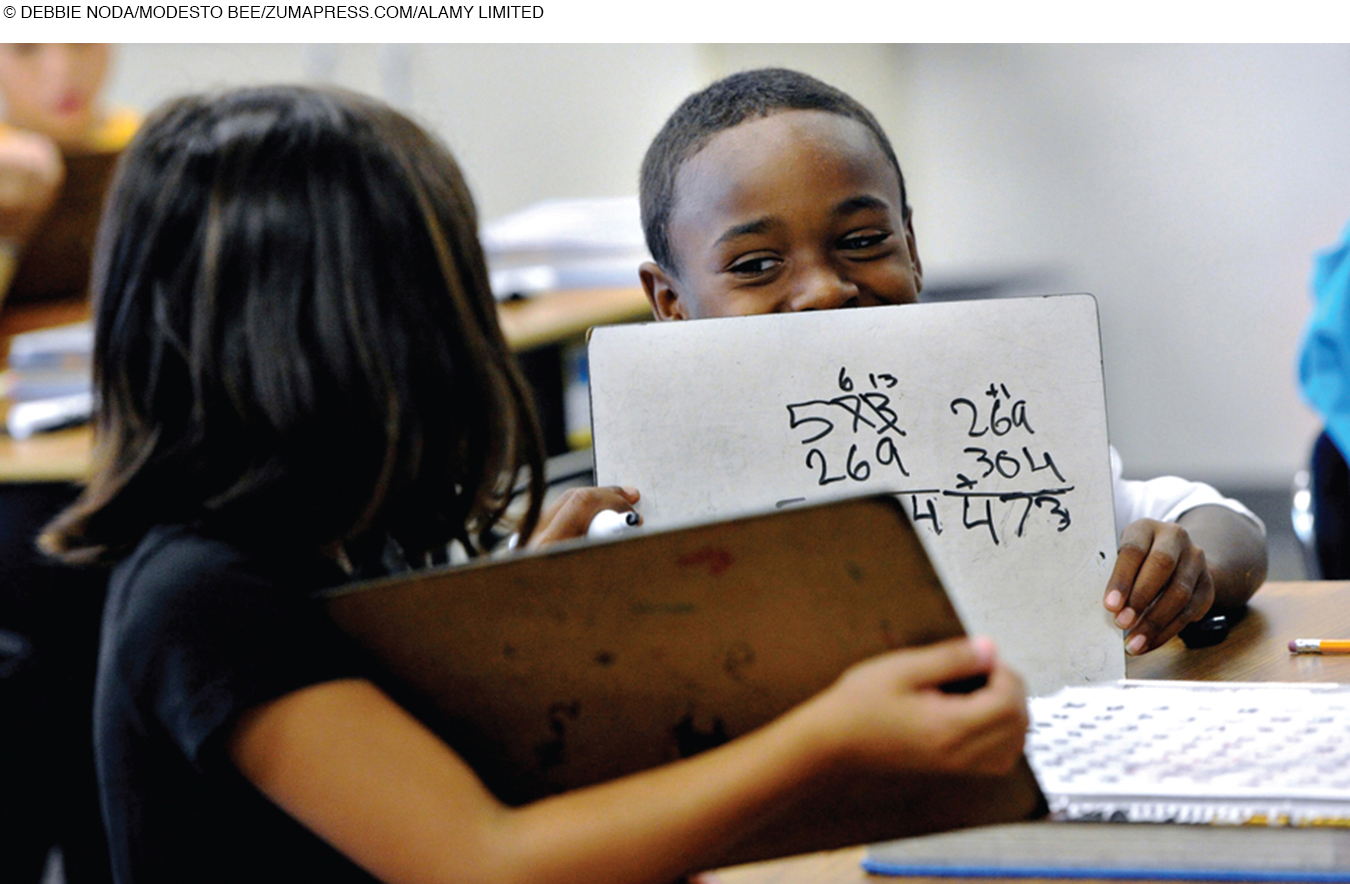

Al wanted to find out how much his cat weighed. He weighed himself and noted that the scale read 57 kg. He then stepped on the scale holding his cat and found that it read 62 kg. What was the weight of the cat in kilograms?

This problem involves simple subtraction, yet 40 percent of U.S. fourth-

A CASE TO STUDY

Encouraging Child Learning

Remember that school-

In one study, more than 200 married, middle-

The researchers found that the Taiwanese mothers were about 50 percent more likely to mention what the researchers called “learning virtues,” such as practice, persistence, and concentration. The American mothers were 25 percent more likely to mention “positive affect,” such as happiness and pride.

This distinction is evident in the following two cases:

First, Tim and his American mother discussed a “not perfect” incident.

Mother: I wanted to talk to you about . . . that time when you had that one math paper that . . . mostly everything was wrong and you never bring home papers like that. . . .

Tim: I just had a clumsy day.

Mother: You had a clumsy day. You sure did, but there was, when we finally figured out what it was that you were doing wrong, you were pretty happy about it . . . . and then you were very happy to practice it. Right? . . . Why do you think that was?

Tim: I don’t know, because I was frustrated, and then you sat down and went over it with me, and I figured it out right with no distraction and then I got it right.

Mother: So it made you feel good to do well?

Tim: Uh-

Mother: And it’s okay to get some wrong sometimes . . .

Tim: And I, I never got that again, didn’t I? . . .

In the next excerpt, Ren and his Taiwanese mother discuss a “good attitude or behavior.”

Mother: Oh, why does your teacher think that you behave well? . . .

Ren: It’s that I concentrate well in class.

Mother: Is your good concentration the concentration to talk to your peer at the next desk?

Ren: I listen to teachers.

Mother: Oh, is it so only for Mr. Chang’s class or is it for all classes?

Ren: Almost all classes like that. . . .

Mother: Uh-

Ren: Yes.

Mother: Or is it also that you yourself want to behave better?

Ren: Yes. I also want to behave better myself.

[Li et al., 2014, p. 1218]

Both Tim and Ren are likely to be good students in their respective schools. When parents support and encourage their child’s learning, almost always the child masters the basic skills required of elementary school students. Such children have sufficient strengths to overcome most challenging life experiences (Masten, 2014).

However, the specifics of parental encouragement affect achievement. Some research has found that parents in Asia emphasize the hard work required to learn, whereas parents in North America stress the joy of learning. The result, according to one group of researchers, is that U.S. children are happier but less accomplished than Asian ones (Ng et al., 2014).

Many educators in the United States have tried to figure out what makes students in some nations do much better than those in others. A recent example is Finland, where scores have improved dramatically in the twenty-

Those changes may be crucial, or the teachers themselves may be the pivotal difference. Finnish teachers have more autonomy to decide what to do and when to do it than is typical in other systems. Since the 1990s, they have also had more time and encouragement to work with colleagues than is true elsewhere.

Finland designs school buildings to foster collaboration, with comfortable teacher’s lounges (Sparks, 2012). That reflects a hidden curriculum regarding teachers. Many Finns want to be teachers, and teacher colleges are free, but only the top 3 percent of Finland’s high school graduates are admitted to them. They must study for five years before they are ready to teach the children.

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN SCHOOL PERFORMANCE In addition to marked national, ethnic, and economic differences, gender differences in international achievement scores are reported. The PIRLS finds girls ahead of boys in verbal skills in every nation by an average of 16 points, almost 4 percent. The female advantage is somewhat less in the United States (10 points), Canada, Germany, and the Netherlands.

Traditionally, boys were ahead of girls in math and science. However, the 2011 TIMSS reported that gender differences among fourth-

In many nations, girls are ahead in math, sometimes by a great deal, such as 14 points in Thailand. Such results lead to a gender-

THINK CRITICALLY: What might have been a biological explanation for gender differences in science achievement?

Video Activity: Educating the Girls of the World examines the situation of girls’ education around the world while stressing the importance of education for all children.

Classroom performance during elementary school shows more gender differences than tests do. Girls have higher report card grades overall, including in math and science.

Then, at puberty, girls’ grades dip, especially in science. In college, fewer women choose STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) majors, and even fewer pursue STEM careers. For instance, in the United States as in most nations, although women earn more college degrees than men, in 2011 only 22 percent of the doctorates in engineering were awarded to women (Snyder & Dillow, 2013).

Many explanations have been suggested. Analysts once blamed the female brain or body; currently the blame often falls on culture (Kanny et al., 2014).

Schools in the United States

Although most national tests indicate improvements in U.S. children’s academic performance over the past decade, when U.S. children are compared with children in other nations, they are far from the top. The rank of the United States is below several other nations, not only those in East Asia but also some in eastern and western Europe (see Tables 7.2 and 7.3).

| Country | Score |

|---|---|

| Hong Kong | 571 |

| Russia | 568 |

| Finland | 568 |

| Singapore | 567 |

| N. Ireland | 558 |

| United States | 556 |

| Denmark | 554 |

| Chinese Taipei | 553 |

| Ireland | 552 |

| England | 552 |

| Canada | 548 |

| Italy | 541 |

| Germany | 541 |

| Israel | 541 |

| New Zealand | 531 |

| Australia | 527 |

| Poland | 526 |

| France | 520 |

| Spain | 513 |

| Iran | 457 |

| Colombia | 448 |

| Indonesia | 428 |

| Morocco | 310 |

| Data from Mullis et al., 2012. | |

| Rank* | Country | Score |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Singapore | 606 |

| 2. | Korea | 605 |

| 3. | Hong Kong | 602 |

| 4. | Chinese Taipei | 591 |

| 5. | Japan | 585 |

| 6. | N. Ireland | 562 |

| 7. | Belgium | 549 |

| 8. | Finland | 545 |

| 9. | England | 542 |

| 10. | Russia | 542 |

| 11. | United States | 541 |

| 12. | Netherlands | 540 |

| Canada (Quebec) | 533 | |

| Germany | 528 | |

| Canada (Ontario) | 518 | |

| Australia | 516 | |

| Italy | 508 | |

| Sweden | 504 | |

| New Zealand | 486 | |

| Iran | 431 | |

| Yemen | 248 | |

| *The top 12 groups are listed in order, but after that not all the jurisdictions that took the test are listed. Some nations have improved over the past 15 years (notably, Hong Kong, England) and some have declined (Austria, Netherlands), but most continue about where they have always been. | ||

| Data from Provasnik et al., 2012. | ||

THE ETHNIC AND ECONOMIC GAP A particular concern is the gap between children of various ethnic and income households, a gap much wider in the United States than in other nations, including some (e.g., Canada) that have more ethnic groups and immigrants than the United States.

Although many U.S. educators and political leaders (including all the recent presidents) have attempted to eradicate performance disparities linked to a child’s background, the gap between fourth-

One reason may be that each state and each school district in the United States determines school policy and funding. Local economic policies and investment in education are thought to be the reason that Massachusetts and Minnesota are consistently at the top of state achievement, and West Virginia, Mississippi, and New Mexico are at the bottom (Pryor, 2014). Similarly within states, the affluent suburbs tend to have smaller classes, bigger playgrounds, and more extracurricular activities than the cities.

No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB)

A U.S. law enacted in 2001 that was intended to increase accountability in education by requiring states to qualify for federal educational funding by administering standardized tests to measure school achievement.

NATIONAL STANDARDS International comparisons as well as disparities within the United States led to passage of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) of 2001, a federal law promoting high national standards for public schools. One controversial aspect of the law is that it requires frequent testing to measure whether standards are being met. Low-

Most people agree with the NCLB goals (accountability and higher achievement) but not with the consequences (Frey et al., 2012). The NCLB troubles those who value the arts, social studies, or physical education because those subjects are often squeezed out by reading and math (Dee et al., 2013). Teacher evaluation and training has increased, but class size has not decreased. Many parents and educators are critical of tests because they undercut creative teaching and character building.

National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)

An ongoing and nationally representative measure of U.S. children’s achievement in reading, mathematics, and other subjects over time; nicknamed “the Nation’s Report Card.”

Since 1990, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), a federally sponsored test of fourth-

Concern about variability in state tests and standards led the governors of all 50 states to designate a group of experts who developed a Common Core of standards, finalized in 2010, for use nationwide. The standards, more rigorous than most state standards, are quite explicit, with half a dozen or more specific expectations for achievement in each subject for each grade. (Table 7.4 provides a sample of the specific standards.)

| Grade | Reading and Writing | Math |

|---|---|---|

| Kindergarten | Pronounce the primary sound for each consonant | Know number names and the count sequence |

| First | Decode regularly spelled one- |

Relate counting to addition and subtraction (e.g., by counting 2 more to add 2) |

| Second | Decode words with common prefixes and suffixes | Measure the length of an object twice, using different units of length for the two measurements; describe how the two measurements relate to the size of the unit chosen |

| Third | Decode multisyllabic words | Understand division as an unknown- |

| Fourth | Use combined knowledge of all letter– |

Apply and extend previous understandings of multiplication to multiply a fraction by a whole number |

| Fifth | With guidance and support from peers and adults, develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach | Graph points on the coordinate plane to solve real- |

| Adapted from National Governors Association, 2010. | ||

As of 2013, forty-

Most teachers were initially in favor of the Common Core, but implementation has turned many against it. In 2013, a poll found only 12 percent of teachers were opposed to the Common Core; a year later, 40 percent were (Gewertz, 2014). Likewise, many state legislators as well as the general public have doubts about the Common Core. This is another example of a general finding: Issues regarding how best to teach children, and what they need to learn, are controversial among teachers, parents, and political leaders.

Choices and Complications

An underlying issue for almost any national or international school is the proper role of parents. In most nations, matters regarding public education—

In the United States, however, local districts provide most of the funds and guidelines, and parents, as voters and volunteers, are often active within their child’s school. As part of the trend toward fewer children per family, parents focus more on each child. They evaluate schools, befriend their child’s teacher, join parent–

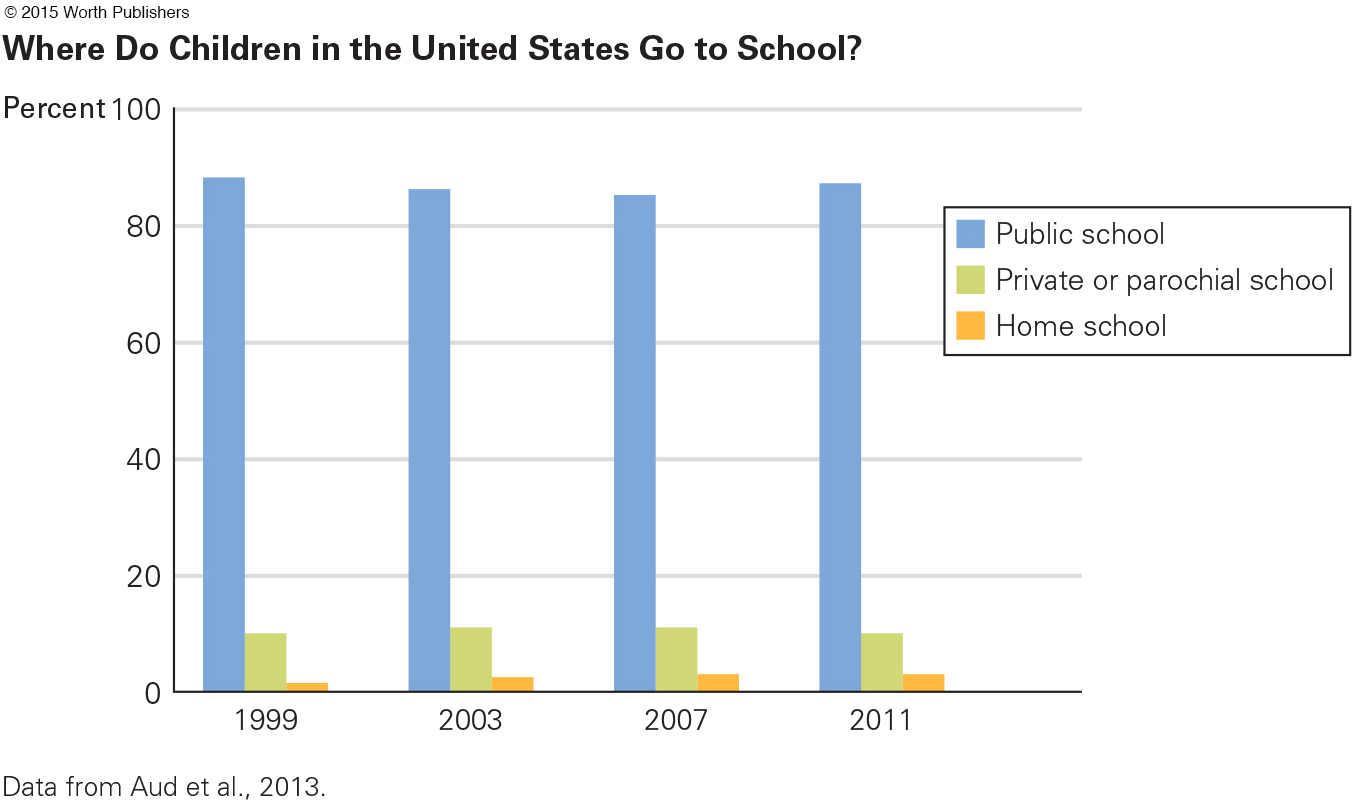

Most U.S. parents send their children to their zoned public school, but almost one-

The existence of education options creates a problem for parents. It is hard to judge the quality of a school, partly because neither test scores nor the values a particular school may espouse correlate with the cognitive skills or learning potential that developmentalists recognize in middle childhood (Finn et al., 2014).

charter schools

Public schools with their own set of standards funded and licensed by the state or local district in which they are located.

CHARTER SCHOOLS In the United States, charter schools are public schools funded and licensed by states or local districts. Typically, they also have private money and sponsors. They are exempt from some regulations, especially those negotiated by teacher unions (hours, class size, etc.), and they have some control over admissions and expulsions. They tend to be more ethnically and economically segregated and enroll fewer children with special needs (Stern et al., 2015).

On average, charter school teachers are younger and work longer hours than regular public school teachers, and school size is smaller than in traditional public schools. Perhaps 5 percent of U.S. children are in charter schools.

Some charter schools are remarkably successful; others are not (Peyser, 2011). A major criticism is that not every child who enters a charter school stays to graduate; one scholar reports that “the dropout rate for African–

Overall, children and teachers leave charter schools more often than they leave regular public schools, a disturbing statistic. Substantial variation is evident from state to state and school to school (some schools are sought by many parents; some are avoided for good reasons), which makes it difficult to judge charters as a group.

private schools

Schools funded by parents and sponsoring institutions. Such schools have control over admissions, hiring, and specifics of curriculum, although some regulations apply.

PRIVATE SCHOOLS Private schools are funded by tuition, endowments, and church sponsors. Every nation has private schools. Traditionally in the United States, most private schools were parochial (church-

All told, 11 percent of students in the United States attend private schools. Economic factors are a major concern: Since private schools get very limited public funding, tuition costs mean that few private-

vouchers

A monetary commitment by the government to pay for the education of a child. Vouchers vary a great deal from place to place, not only in amount and availability, but in who gets them and what schools accept them.

To solve that disparity, some U.S. jurisdictions issue vouchers, which parents can use to pay tuition at a private school, including a church-

home schooling

Education in which children are taught at home, usually by their parents, instead of attending any school, public or private.

HOME EDUCATION Every child learns more at home than at school, but some parents avoid sending their children to any school. Instead, they choose home schooling, educating their children exclusively at home. Home schooling is an option in 35 of the 50 states in the United States, and in some—

This choice is more common for younger children—

Numbers are not expected to increase much more, however, because home schooling requires an adult at home, typically the mother in a two-

The major problem with home schooling is not academic (some home-

HOW TO DECIDE? The underlying problem with all these options is that people disagree about what is best and how learning should be measured. For example, many parents consider class size: They may choose private school because fewer students are in each class. Some parents want children to have homework, beginning in the first grade. Yet few developmentalists are convinced that small classes or homework are essential for learning during middle childhood.

Mixed evidence comes from nations where children score high on international tests. Sometimes they have large student–

Question 7.21

OBSERVATION QUIZ

The photo shows Marissa’s students congratulating their teacher. What do you see in the hidden curriculum?

All the closest students are girls. What have the boys learned that is not part of the official curriculum?

Who should decide what children should learn and how? Statistical analysis raises questions about home schooling and about charter schools (Lubienski et al., 2013; Finn et al., 2014), but as our discussion of NAEP, Common Core, TIMSS, and so on makes clear, the evidence allows many interpretations. As one review notes, “the modern day, parent-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 7.22

1. How does a child’s age affect the understanding of metaphors and jokes?

A child has to have a good grasp of pragmatics before he or she can appreciate metaphors or jokes that make a play on words.

Question 7.23

2. Why would a child’s linguistic code be criticized by teachers but admired by friends?

The informal code used with friends often includes curse words, slang, gestures, and intentionally incorrect grammar. Peers approve of such violations, whereas adults wish to teach children the formal code of standard speech based on grammatical rules.

Question 7.24

3. What factors in a child’s home and school affect language-

In the United States, almost one out of four school-

Question 7.25

4. How does the hidden curriculum differ from the stated school curriculum?

The stated curriculum comes from the textbook. The hidden curriculum is what happens during the transmission of knowledge and may be a largely unconscious process.

Question 7.26

5. What are the TIMSS and the PIRLS?

The Trends in Math and Science Study (TIMSS) is an international assessment of the math and science skills of fourth-

Question 7.27

6. What nations score highest on international tests?

East Asian nations rank near the top on the TIMSS and PIRLS.

Question 7.28

7. How do boys and girls differ in school achievement?

The PIRLS finds that in every nation, girls score higher than boys in verbal skills. Traditionally, boys have been ahead of girls in math and science, but in many nations, girls are now ahead in math, sometimes by a great deal. Classroom performance during elementary school shows more gender differences than tests do. Girls have higher report card grades overall, including higher grades in math and science. Then, at puberty, girls’ grades dip, especially in science.

Question 7.29

8. What problems do the Common Core standards attempt to solve?

The Common Core standards were created to establish rigorous standards and appropriate assessments to meet the No Child Left Behind Act guidelines. These standards are very specific and precise; students either meet them or they do not.

Question 7.30

9. How do charter schools, private schools, and home schools differ?

Charter schools are public schools with additional funding from private sources. They control student admission and expulsion and often have some exemptions from state regulations. Private schools are funded by tuition from families as well as private sources and can be religious or secular in nature. Home schooling is when parents educate their own children at home.

Question 7.31

10. How do parents choose what school is best for their children?

Parents evaluate class size, homework load, and teacher-