Children’s Moral Values

Middle childhood is prime time for moral development. Many forces drive children’s growing interest in moral issues. Three of them are (1) peer norms, (2) personal experience, and (3) empathy. The culture of children includes moral values, such as loyalty to friends and keeping secrets. Personal experiences also matter.

For all children, empathy increases in middle childhood as children become more socially perceptive. This increasing perception can backfire, however. One example was just described: Bullies become adept at picking victims (Veenstra et al., 2010). An increase in social understanding makes noticing and defending rejected children possible, but in some social contexts, bystanders may decide to be self-

Children who are slow to develop theory of mind—

The authors of a study of 7-

Question 8.28

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Why is Krysta’s poster a good example of Erikson’s industry versus inferiority stage?

The industry stage emphasizes being busy and careful. Each square, painstakingly drawn, illustrates a very specific action a citizen can take. l

Moral Reasoning

Piaget wrote extensively about the moral development of children, as they developed and enforced their own rules for playing games together (Piaget, 1932/2013). His emphasis on how children think about moral issues led to a famous description of cognitive stages of morality (Kohlberg, 1963).

KOHLBERG’S LEVELS OF MORAL THOUGHT Lawrence Kohlberg described three levels of moral reasoning and two stages at each level (see Table 8.3), with parallels to Piaget’s stages of cognition.

preconventional moral reasoning

Kohlberg’s first level of moral reasoning, emphasizing personal rewards and punishments.

Preconventional moral reasoning is similar to preoperational thought in that it is egocentric, with children most interested in their personal pleasure or avoiding punishment.

conventional moral reasoning

Kohlberg’s second level of moral reasoning, emphasizing social rules and laws.

Conventional moral reasoning parallels concrete operational thought in that it relates to current, observable practices: Children watch what their parents, teachers, and friends do, and they try to follow suit.

postconventional moral reasoning

Kohlberg’s third level of moral reasoning, emphasizing moral principles.

Postconventional moral reasoning is similar to formal operational thought because it uses abstractions, going beyond what is concretely observed, willing to question “what is” in order to decide “what should be.”

According to Kohlberg, intellectual maturation advances moral thinking. During middle childhood, children’s answers shift from being primarily preconventional to being more conventional: Concrete thought and peer experiences help children move past the first two stages (level I) to the next two (level II). Postconventional reasoning (level III) is not usually present until adolescence or adulthood, if then.

Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to boys (and eventually girls, adolescents, and adults). The most famous of these dilemmas involves a poor man named Heinz, whose wife was dying. He could not afford the only drug that could save his wife, which the druggist sold for 10 times what it cost to make.

Heinz went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he could only get together about half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later. But the druggist said “no.” The husband got desperate and broke into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife. Should the husband have done that? Why?

[Kohlberg, 1963, p. 19]

|

Level I: Preconventional Moral Reasoning The goal is to get rewards and avoid punishments; this is a self-

|

|

Level II: Conventional Moral Reasoning Emphasis is placed on social rules; this is a parent-

|

|

Level III: Postconventional Moral Reasoning Emphasis is placed on moral principles; this level is centered on ideals.

|

The crucial element in Kohlberg’s assessment of moral stages is not what a person answers but the reasons given. For instance, suppose a child says that Heinz should steal the drug. That itself does not indicate the child’s level of moral reasoning. The reason could be that Heinz needs his wife to care for him (preconventional), or that people will blame him if he lets his wife die (conventional), or that a human life is more important than obeying a law (postconventional).

Or suppose another child says Heinz should not steal. The reason could be that he will go to jail (preconventional), or that stealing is against the law (conventional), or that for a community to function, no one should jeopardize another person’s livelihood (postconventional).

CRITICISMS OF KOHLBERG Kohlberg has been criticized for not appreciating cultural or gender differences. For example, in some cultures, loyalty to family overrides any other value, so highly moral people might avoid postconventional actions that hurt their family. Also, Kohlberg’s original participants were all boys, which may have led him to discount nurturance and relationships, thought to be more valued by females than males (Gilligan, 1982).

Kohlberg seemed to value abstract principles more than individual needs and to prioritize rational thinking. However, critics suggest that emotions may be more influential than logic in moral development (Haidt, 2013). Thus, emotional regulation, empathy, and social understanding, all of which develop throughout childhood, may be more crucial for morality than intellectual development is.

Finally, Kohlberg did not seem to recognize that, although children’s morality differs from that of adults, they may be quite moral. If a child questions adult rules that seem unfair, as often occurs in middle childhood (Turiel, 2006, 2008), that may indicate postconventional thinking.

In one respect, however, Kohlberg was undeniably correct. He was right in noting that people use their intellect to justify their morality. In one experiment, children aged 8 to 18 were grouped with two others of about the same age and allotted some money. They were then asked to decide how much to share with another trio of children.

Surprisingly, there were no age trends in the resulting decisions: Some young and some older groups chose to share equally, and other groups of both ages were more selfish. However, the justifications showed age differences. Older children suggested more complex rationalizations for their choices, both selfish and altruistic (Gummerum et al., 2008).

What Children Value

Many lines of research have shown that children develop their own morality, guided by peers, parents, and culture (Killen & Smetana, 2014). Some prosocial values are evident in early childhood. Among these values are caring for close family members, cooperating with other children, and not hurting anyone intentionally. Even very young children think stealing is wrong, and even infants seem to appreciate social support and punish mean behavior (Hamlin, 2014).

As children become more aware of themselves and others in middle childhood, they realize that one person’s values may conflict with another’s. Concrete operational cognition, which gives children the ability to understand and use logic, propels them to think about moral rules. In the opening anecdote of this chapter, a boy argued that it was “so unfair” that he could not kill zombies. Fairness is a prime moral value in middle childhood.

ADULTS VERSUS PEERS When child culture conflicts with adult morality, children often align themselves with peers. A child might lie to protect a friend, for instance. Friendship itself has a hostile side: Many close friends reject other children who want to join their game or conversation (Rubin et al., 2013). They may also protect a bully if he or she is a friend.

The conflict between the morality of children and that of adults is evident in the value that children place on education. Adults usually prize school and respect teachers, but children may encourage one another to skip class, cheat on tests, harass a substitute teacher, and so on.

Three common moral imperatives among 6-

Protect your friends.

Don’t tell adults what is happening.

Conform to peer standards of dress, talk, and behavior.

These principles can explain both apparent boredom and overt defiance, as well as standards of dress that mystify adults (such as jeans so loose that they fall off or so tight that they impede digestion—

This conflict is evident in one boy who was aware of the moral values of his local church but who also wanted to be part of his peer group. Paul said:

I think right now about going Christian, right? Just going Christian, trying to do good, you know? Stay away from drugs, everything. And every time it seems like I think about that, I think about the homeboys. And it’s a trip because a lot of the homeboys are my family, too, you know?

[quoted in Nieto, 2000, p. 249]

Fortunately, peers may help one another act ethically. Children are better at stopping bullying than adults are, because bystanders are pivotal. Since bullies tend to be low on empathy, they need peers to tell them they are mistaken if they think classmates admire their aggression.

THINK CRITICALLY: If one of your moral values differs from your spouse, your parents, or your community, should you still try to teach it to your children? Why or why not?

None of this means that parents, teachers, and religious institutions are irrelevant. During middle childhood, morality can be scaffolded just as cognitive skills are, with mentors—

DEVELOPING MORAL VALUES Over the years of middle childhood, moral judgment becomes more comprehensive. Gradually children become better at taking psychological as well as physical harm into account, considering intentions as well as consequences.

For example, in one study 5-

When the harm was psychological, not physical (hurting the child’s feelings, not hitting), more than half of the older children considered intentions, but only about 5 percent of the younger children did. Compared to the younger children, the older children were more likely to say justifiable harm was OK but unjustifiable harm should be punished (Jambon & Smetana, 2014).

Another detailed examination of morality began with an update on one of Piaget’s moral issues: whether punishment should seek retribution (hurting the transgressor) or a more mature punishment called restitution (restoring what was lost). Piaget found that children advance from retribution to restitution between ages 8 and 10 (Piaget, 1932/2013).

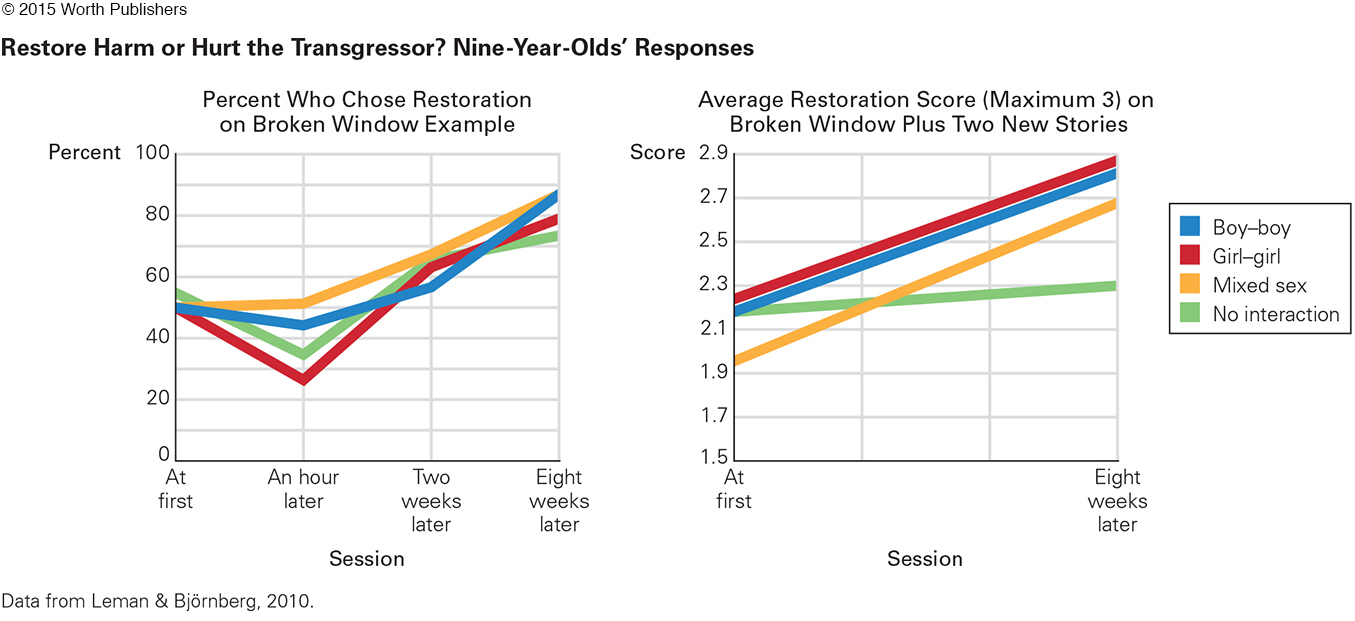

To learn how this occurs, researchers asked 133 9-

Late one afternoon there was a boy who was playing with a ball on his own in the garden. His dad saw him playing with it and asked him not to play with it so near the house because it might break a window. The boy didn’t really listen to his dad, and carried on playing near the house. Then suddenly, the ball bounced up high and broke the window in the boy’s room. His dad heard the noise and came to see what had happened. The father wonders what would be the fairest way to punish the boy. He thinks of two punishments. The first is to say: “Now, you didn’t do as I asked. You will have to pay for the window to be mended, and I am going to take the money from your pocket money.” The second is to say: “Now, you didn’t do as I asked. As a punishment you have to go to your room and stay there for the rest of the evening.” Which of these punishments do you think is the fairest?

[Leman & Björnberg, 2010, p. 962]

Initially, the children were split almost equally between retribution (stay in your room) and restoration (pay for the window). Then 24 pairs were formed of children who had opposite views. Each pair was asked to discuss the issue, trying to reach agreement. (The other children did not discuss it.) Six pairs were boy–

The conversations typically took only five minutes, and the retribution side was more often chosen. Piaget would consider that a moral backslide, since he thought retribution was less mature. Several weeks later all the children were queried again. At that point, many responses changed toward the more advanced, restitution response (see Figure 8.1). Some of the children who had not discussed it with a peer switched, but children who had discussed it with another child were particularly likely to conclude that restitution was best.

The researchers wrote, “conversation on a topic may stimulate a process of individual reflection that triggers developmental advances” (Leman & Björnberg, 2010, p. 969). Parents and teachers take note: Raising moral issues, and letting children discuss them, advances morality—

Think again about the opening anecdote for this chapter (killing zombies). The parent used age as a criterion, and the child rejected that argument. A better argument might raise a higher standard, for instance that killing, even in fantasy, is not justified. The child might disagree, but such conversations might help the child think more deeply about moral values. That deeper thought might protect the child during adolescence, when life-

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 8.29

1. Using your own example, illustrate Kohlberg’s three levels of moral reasoning.

Answers will vary, but an example for each level is listed below.

(1) Preconventional moral reasoning: A child follows his teacher’s rules respectfully when other children are misbehaving because he knows his teacher will take notice and praise him in front of the other children.

(2) Conventional moral reasoning: A child refuses to cross the street while walking with her father because he is not at a designated crosswalk.

(3) Postconventional reasoning: A teenager declines to go deer hunting with a group of his close friends despite their repeated urging and teasing because he believes the practice of hunting is unethical.

Question 8.30

2. What are the main criticisms of Kohlberg’s theory?

Kohlberg has been criticized for ignoring cultural and gender differences—

Question 8.31

3. When would family values overtake national values?

Answers may vary, but as children develop more prosocial values, they also realize that their own values (or those of their family) may conflict with another’s (or those of their culture or nation). They may disagree with their country’s decision to go to war, to cut assistance to the elderly or poor, etc.

Question 8.32

4. How might children’s morality differ from adult morality?

When children’s values clash with adult values, children often side with their peers, perhaps lying to protect a friend. And while adults usually prize school and respect teachers, children may encourage each other to misbehave, cheat, etc. Children are also better at stopping bullying than are adults, because they expect bullies to conform to their rigid standards of behavior.

Question 8.33

5. How might the morality of children help stop a bully?

Most victimized children find ways to halt ongoing bullying, by ignoring, retaliating, defusing, or avoiding. Friends can defend each other and restore self-

Question 8.34

6. What kind of punishment did Piaget think was more advanced morally?

He believed restitution—

Question 8.35

7. What seems to advance moral thought during middle childhood?

When parents and teachers raise moral issues and let children discuss them, a process of individual reflection is stimulated that eventually advances morality.