Puberty

Puberty refers to the years of rapid physical growth and sexual maturation that end childhood, producing a person of adult size, shape, and sexuality. The forces of puberty are unleashed by a cascade of hormones that produce external growth and internal changes, including heightened emotions and sexual desires.

Average Ages and Changes

The process of puberty normally starts sometime between ages 8 and 14, and most physical changes are complete within four years—

Video: The Timing of Puberty

menarche

A girl’s first menstrual period, signalling that she has begun ovulation. Pregnancy is biologically possible, but ovulation and menstruation are often irregular for years after menarche.

For girls, the observable changes of puberty usually begin with nipple growth. Soon a few pubic hairs are visible, followed by a peak growth spurt, widening of the hips, menarche (the first menstrual period), full pubic-

spermarche

A boy’s first ejaculation of sperm. Erections can occur as early as infancy, but ejaculation signals sperm production. Spermarche may occur during sleep (in a “wet dream”) or via direct stimulation.

For boys, the usual sequence is growth of the testes, initial pubic-

pituitary

A gland in the brain that produces many hormones, including those that regulate growth and that signal the adrenal and sex glands to produce additional hormones.

adrenal glands

Two glands, located above the kidneys, that produce hormones in response to signals from the pituitary.

HORMONES Puberty begins before those observable changes with an invisible event—

| Girls | Approximate Average Age* | Boys |

|---|---|---|

| Ovaries increase production of estrogen and progesterone** | 9 | |

| Uterus and vagina begin to grow larger | 9½ | Testes increase production of testosterone** |

| Breast “bud” stage | 10 | Testes and scrotum grow larger |

| Pubic hair begins to appear; weight spurt begins | 11 | |

| Peak height spurt | 11½ | Pubic hair begins to appear |

| Peak muscle and organ growth; hips become noticeably wider | 12 | Penis growth begins |

| Menarche (first menstrual period) | 12½ | Spermarche (first ejaculation); weight spurt begins |

| First ovulation | 13 | Peak height spurt |

| Voice lowers | 14 | Peak muscle and organ growth; shoulders become noticeably broader |

| Final pubic- |

15 | Voice lowers; visible facial hair |

| Full breast growth | 16 | |

| 18 | Final pubic- |

|

| *Average ages are rough approximations, with many perfectly normal, healthy adolescents as much as three years behind these ages. | ||

| **Estrogen and testosterone influence sexual characteristics, including reproduction. Charted here are the increases produced by the gonads (sex glands). The ovaries produce estrogens and the testes produce androgens, especially testosterone. Adrenal glands produce some of both kinds of hormones (not shown). | ||

gonads

The sex glands (ovaries in females, testicles in males). The gonads produce hormones and gametes.

estradiol

A sex hormone, considered to be the chief estrogen (female hormone). Females produce much more estradiol than males do.

testosterone

A sex hormone, the best known of the androgens (male hormones); secreted in far greater amounts by males than by females.

The pituitary also activates the gonads, or sex glands (ovaries in females; testes, or testicles, in males). One hormone in particular, GnRH (gonadotropin-

Estrogens (including estradiol) are female hormones and androgens (including testosterone) are male hormones, although both sexes have some of both. The ovaries produce high levels of estrogens and the testes produce dramatic increases in androgens. This “surge of hormones” affects bodies, brains, and behavior before any visible signs of puberty appear, “well before the teens” (Peper & Dahl, 2013, p. 134).

The activated gonads begin to release ova (at menarche) or sperm (at spermarche). Conception is possible, although peak fertility occurs four to six years later. Hormones also awaken interest in sex, as young teenagers fantasize—

Hormones may underlie differences in psychopathology. Compared to the other sex, adolescent males are almost twice as likely to develop schizophrenia and adolescent females more than twice as likely to develop major depression. Of course, hormones are never the sole cause of psychopathology (Tackett et al., 2014; Rudolph, 2014).

Remember that body, brain, and behavior always interact. Sexual thoughts themselves can cause physiological and neurological processes, not just result from them. Cortisol (another hormone) levels rise at puberty, and that makes adolescents quicker to become angry or upset (Goddings et al., 2012; Klein & Romeo, 2013).

THINK CRITICALLY: If a child seems to be unusually short, or unusually slow in reaching puberty, would you give the child hormones? Why or why not?

Then emotions, in turn, increase hormones. For example, when other people react to emerging breasts or beards, that evokes thoughts and frustrations in the adolescent, which raises hormone levels, propels physiological development, and triggers more emotions. Thus the internal and external changes each affect the other.

circadian rhythm

A day–

BODY RHYTHMS The brain of every living creature responds to the environment with natural rhythms that rise and fall by the day and season. For example, in children, height increases more rapidly in summer and weight in winter. Many rhythms are circadian, which means they are on a daily cycle. That is why well-

In addition, some individuals (especially males) are more alert in the evening than in the morning. Other people are the opposite, filled with energy in the morning and then fading as the day wears on. Those differences are genetic.

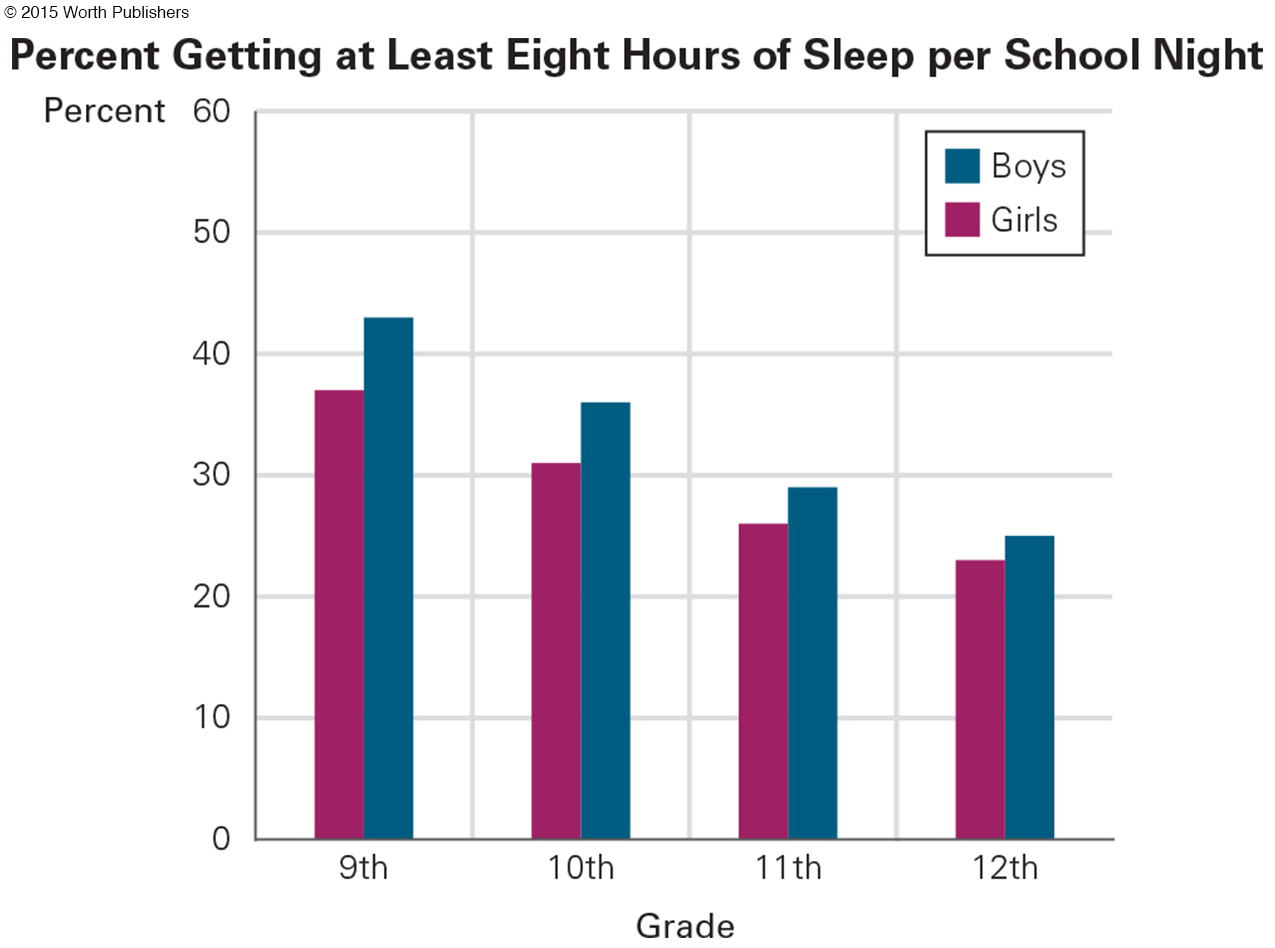

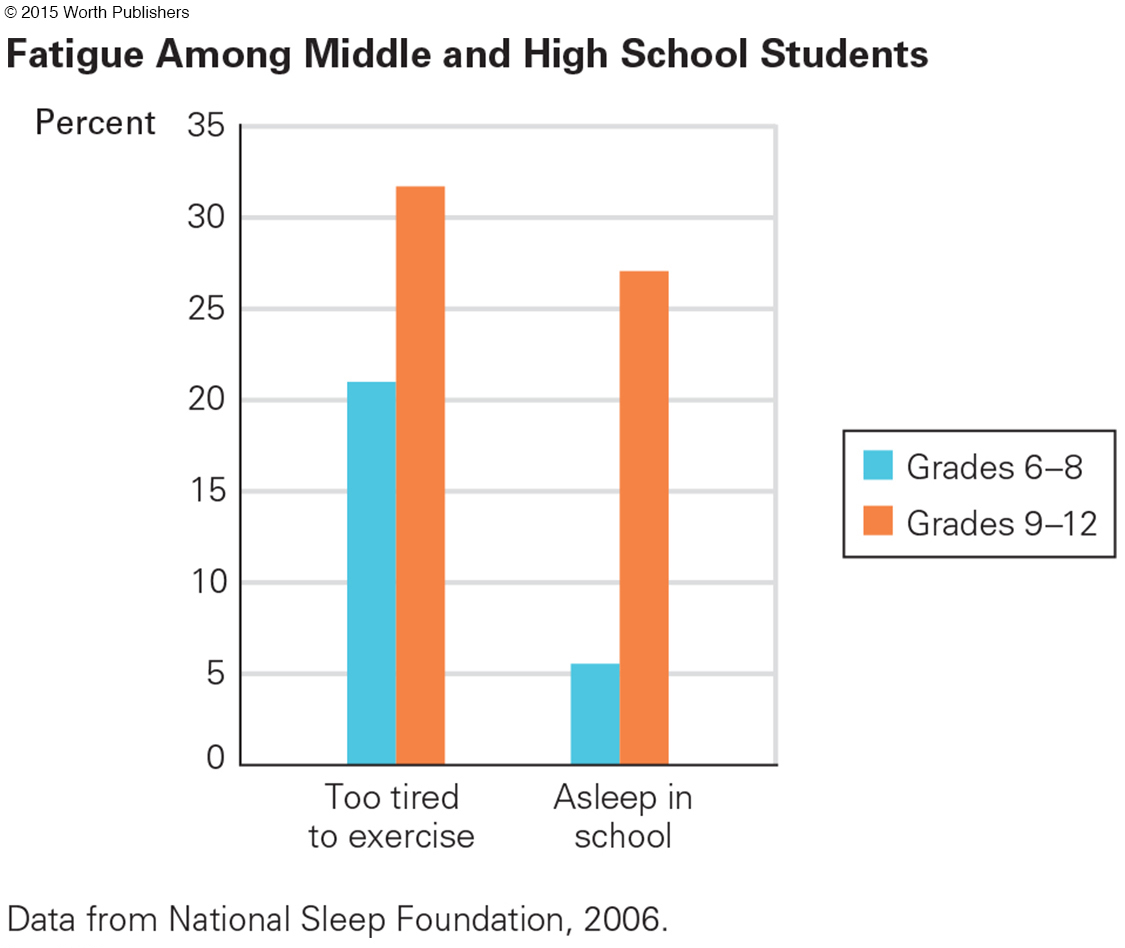

In addition, at puberty, hormones cause a phase delay in the circadian sleep–

Question 9.1

OBSERVATION QUIZ

As you see, the problems may be worse for girls. Why is that?

Girls tend to spend more time studying, talking to friends, and getting ready in the morning. Other data show that many girls get less than seven hours of sleep per night.

To make it worse, “the blue spectrum light from TV, computer, and personal-

Sleep deprivation and irregular sleep schedules increase the risk of insomnia, nightmares, mood disorders (depression, conduct disorder, anxiety), and falling asleep while driving. In addition, sleepy people don’t learn as well as they do when rested. Many adults ignore these facts, as the following explains.

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Algebra at 7 A.M.? Get Real!

Adults sometimes fight against what is natural to adolescents. This is evident with sexual curiosity (“you’re too young to think about boys”) and circadian rhythm (“go to sleep, you need to get up for school”).

Many adults think adolescents belong at home, just when many adolescents much prefer to be with friends. In 2014, Baltimore implemented a law that required young adolescents (under age 14) to be home by 9 P.M. and older ones (14-

For many adolescent bodies, early sleep and then early rising are almost impossible. As a result, many sleep-

Data on the circadian rhythm and the teenage brain convinced social scientists at the University of Minnesota to ask 17 school districts to start high school later. Parents disagreed. Many (42 percent) thought high school should begin before 8:00 A.M. Some (20 percent) wanted their teenagers out of the house by 7:15 A.M. (Wahlstrom, 2002).

Other adults had their own reasons for wanting high school to begin early. Teachers thought that learning was more efficient in the morning; bus drivers hated rush hour; cafeteria workers liked to go home in mid-

Initially only one Minnesota school district (Edina) changed the schedule of their high school day, from 7:25–

Other school districts noticed. Minneapolis high schools changed their start time from 7:15 to 8:40. Attendance and graduation rates improved. School boards in South Burlington (Vermont), West Des Moines (Iowa), Tulsa (Oklahoma), Arlington (Virginia), Palo Alto (California), and Milwaukee (Wisconsin) voted to start high school later, from an average of 7:45 to an average of 8:30 (Tonn, 2006; Snider, 2012). Unexpected advantages appeared: more efficient energy use, less adolescent depression, and in Tulsa, unprecedented athletic championships.

Many school districts remain stuck to traditional schedules, scheduling school buses to drop off teenagers and then pick up the younger children. Although “the science is there; the will to change is not” (Snider, 2012).

One example comes from Fairfax County (Virginia) where two opposing groups—

The later start would hinder teams without lighted practice fields. Hinder kids who work after-

[Williams, 2009]

Note that Williams never argued that learning would be reduced, because that would be untrue. He wrote that science was on the side of change but reality was not. To developmentalists, of course, science is reality.

In 2009, the Fairfax school board voted to keep the high school start at 7:20 A.M. The SLEEP advocates kept trying. On the eighth try, the Fairfax school board in 2012 finally set a goal: High schools should not start before 8:00 A.M. They hired a team to figure out how to implement that goal. As of 2014, they had not done so.

There is a new reason to change. In August 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics concluded that high school should not begin until 8:30 or 9:00 A.M., because adolescent sleep deprivation causes intellectual and behavioral problems. They noted that 43 percent of high schools in the United States start before 8:00 A.M. The clash between tradition and science, or between adult expectations and adolescent bodies, continues.

Many Reasons for Variations

That six-

GENES AND GENDER About two-

The other major influence on age of puberty comes from the sex chromosomes. In height, the average girl is two years ahead of the average boy: The female height spurt occurs before menarche, whereas for boys the increase in height is relatively late, after spermarche. Thus, a sixth-

FAT Body fat also affects age of puberty. Heavy girls reach menarche years earlier than malnourished ones do. Most girls weigh at least 100 pounds (45 kilograms) before menarche (Berkey et al., 2000). Although severe malnutrition always delays puberty, body fat may not be as necessary for boys. Indeed, obese boys are often delayed in puberty compared to boys who are neither slim nor overweight (Tackett et al., 2014).

Malnutrition causes many youths to reach puberty at age 15 or later in parts of Africa, whereas their genetic relatives in North America mature much earlier. Similarly, malnutrition is the main reason puberty began at about age 17 in sixteenth-

secular trend

Advances in growth and maturation that result from modern nutrition. For example, improved nutrition and medical care over the past 200 years has led to earlier puberty and taller average height.

Since then, puberty has occurred at younger and younger ages (an example of what is called the secular trend, the increases in human growth as nutrition improved). More food availability led to weight gain in childhood, and that has led to earlier puberty for girls and taller average height for both sexes (Floud et al., 2011; Fogel & Grotte, 2011).

One curious bit of evidence of the secular trend is that U.S. presidents have gotten taller. James Madison, the fourth president, was shortest at 5 feet, 4 inches; Barack Obama is 6 feet, 1 inch tall.

The secular trend seems to have stopped in developed nations, because adequate nutrition allows everyone to reach their genetic potential. Currently, fewer young men look down at their short fathers, or girls at their little mothers, unless their parents were born in Asia or Africa, where the secular trend is still evident.

There is one possible exception in developed nations to the statement “the secular trend has stopped.” Very early puberty, before age 8 (called precocious puberty), may be increasing, especially in girls, although it is still rare (perhaps 2 percent) (Sørensen et al., 2012). Sometimes precocious puberty is genetic (perhaps 20 percent), but the cause of the increase is largely unknown—

Some research finds that puberty is delayed, not accelerated, in boys who were exposed prenatally to phthalates and bisphenol A (K. Ferguson et al., 2014), or who experienced heavy doses of pesticides in boyhood (T. Lam et al., 2014). Phthalates may delay puberty in girls as well (Wolff et al., 2014).

Caution is needed here. No doubt, heavy doses of many chemicals and pesticides affect fish, frogs, insects, and birds, causing reproductive problems. However, as noted in Chapter 2, experts disagree about the impact on humans.

STRESS Stress hastens the hormonal onset of puberty, especially if a child’s parents are sick, drug-

The link between stress and puberty is one explanation for the fact that children born in one country and adopted in another tend to experience early puberty, especially if their first few years of life were in an institution or a chaotic home. An alternate explanation is that their age at adoption was underestimated, so puberty appears to occur early but actually is at the expected time (Hayes, 2013).

Why would cortisol trigger puberty? An answer comes from evolutionary theory. Thousands of years ago, if harsh conditions threatened survival of the species, adolescents needed to reproduce early and often to increase the chance that at least some children would reach adulthood. By contrast, in peaceful times, puberty could occur later, allowing children to postpone maturity and instead enjoy extra years of childhood nurturance from parents and grandparents.

Of course, this evolutionary rationale no longer applies. Today, early sexual activity and teen parenthood are more likely to harm communities than help the species. However, the genome has been shaped over millennia; if there is a puberty-

TOO EARLY, TOO LATE For most adolescents, these links between puberty, stress, and hormones are irrelevant. The only timing that matters is their friends’ schedules. No one wants to be too early or too late.

Question 9.2

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Who is least developed and who is most developed?

Impossible to be sure, but it seems as if the only one smiling is the least developed (note the size of her hands, the narrowness of her hips); the one on the left is the most developed (note hips, facial expression, height, and—

Think about the early-

Some early-

The effects of early maturation on boys depend on context. In the United States, early-

In the twenty-

Late puberty may also be difficult, especially for boys (Benoit et al., 2013). Slow-

Becoming a Grown-Up

growth spurt

The relatively sudden and rapid physical growth that occurs during puberty. Each body part increases in size on a schedule: Weight usually precedes height, and growth of the limbs precedes growth of the torso.

Puberty causes two sets of changes. One set is marked by the growth spurt—a sudden, uneven jump in the size of almost every body part, turning children into adults. The other set is sexual; turning girls and boys into men and women who could become parents.

THE GROWTH SPURT Growth proceeds from the extremities to the core (the opposite of the earlier proximodistal growth). Thus, fingers and toes lengthen before hands and feet, hands and feet before arms and legs, arms and legs before the torso. This growth is not always symmetrical: One foot, one breast, or even one ear may grow later than the other.

Because the torso is the last body part to grow, many pubescent children are temporarily big-

As the growth spurt begins, children eat more and gain weight. Exactly when, where, and how much weight they gain depends on heredity, hormones, diet, exercise, and gender. By age 17, the average girl has twice the percentage of body fat as her male classmate, whose increased weight is mostly muscle.

A height spurt follows the weight spurt; then a year or two later a muscle spurt occurs. Thus, the pudginess and clumsiness of early puberty are usually gone by late adolescence. During these years, all the muscles increase in power.

Inner organs grow as well. Lungs triple in weight, allowing adolescents to breathe more deeply and slowly. The heart doubles in size as the heartbeat slows, decreasing the pulse rate while increasing blood pressure. Consequently, endurance improves: Some teenagers can run for miles or dance for hours. Fortunately, red blood cells increase in both sexes, dramatically more in boys, aiding oxygen transport during intense exercise.

One organ system, the lymphoid system (including tonsils and adenoids), decreases in size, so teenagers are less susceptible to respiratory ailments. As a result, mild asthma often switches off at puberty—

When the larynx grows, the voice lowers, especially noticeable in boys. Another organ system, the skin, becomes oilier, sweatier, and more prone to acne. Hair also changes, becoming coarser and darker, with new hair under arms, on faces, and over sex organs. Specifics depend on genes as well as on hormones.

Often teenagers cut, style, or grow their hair in ways their parents do not like, as a sign of independence. To become more attractive, many adolescents spend considerable time, money, and thought on their visible hair—

primary sex characteristics

The parts of the body that are directly involved in reproduction, including the vagina, uterus, ovaries, testicles, and penis.

SEXUAL CHARACTERISTICS The body characteristics that are directly involved in conception and pregnancy are called primary sex characteristics. During puberty, every primary sex organ (the ovaries, uterus, penis, and testes) increases dramatically in size and matures in function. By the end of the process, reproduction is possible.

secondary sex characteristics

Physical traits that are not directly involved in reproduction but that indicate sexual maturity, such as a man’s beard and a woman’s breasts.

At the same time, development occurs in secondary sex characteristics. They do not directly affect reproduction (hence they are secondary) but signify gender.

One secondary characteristic is shape. Young boys and girls have similar shapes, but at puberty males widen at the shoulders and grow about 5 inches taller than females, while girls widen at the hips and develop breasts. Those curves are considered signs of womanhood, but neither breasts nor wide hips are required for conception; thus, they are secondary, not primary, sex characteristics.

Secondary sex characteristics are important psychologically, if not biologically. Breasts are an obvious example. Many adolescent girls buy “minimizer,” “maximizer,” “training,” or “shaping” bras, hoping that their breasts will conform to their idealized body image.

During the same years, many overweight boys are horrified to notice a swelling around their nipples—

Nutrition

All the changes of puberty depend on adequate nourishment, yet many adolescents do not eat well. They often skip breakfast, binge at midnight, guzzle down unhealthy energy drinks, and munch on salty, processed snacks. Some eat so poorly that their health is damaged lifelong.

NUTRIENTS MISSING Family dinners correlate with healthy adolescent eating and well-

Most adolescents consume enough calories, but in 2013 only 16 percent of high school seniors ate the recommended three or more servings of vegetables a day (MMWR, June 13, 2014). Deficiencies of iron, calcium, zinc, and other minerals are common.

Because menstruation depletes iron, anemia is more likely among adolescent girls than among people of any other age or sex. Boys may also be iron-

The cutoff for iron-

Similarly, although the daily recommended intake of calcium for teenagers is 1,300 milligrams, the average U.S. teen consumes less than 500 milligrams a day. About half of adult bone mass is acquired from ages 10 to 20, which means many contemporary teenagers will eventually develop osteoporosis (fragile bones), a major cause of disability, injury, and death in late adulthood.

One reason for calcium deficiency is that milk drinking has declined. In 1961, most North American children drank at least 24 ounces (about three-

Fast-

Video Activity: Eating Disorders introduces the three main types of eating disorders and outlines the signs and symptoms of each.

body image

A person’s idea of how his or her body looks, especially related to size and shape.

BODY DISSATISFACTION One reason for poor nutrition among teenagers is anxiety about body image—that is, a person’s idea of how his or her body looks. Two-

Body image dissatisfaction occurs in adolescents of both sexes and every ethnic group, although each adolescent is troubled by particular characteristics that spring from their ancestral genes. Film stars and media models make this worse.

Many adolescents obsess about being too short or too tall, too wide in the hips or too narrow in the face, too hairy or not hairy enough, with fingers too long or legs too fat, and so on. Self-

For a few, dissatisfaction with body image can be dangerous, even deadly. Eating disorders are rare in childhood but increase dramatically at puberty, accompanied by distorted body image, food obsession, and depression (Le Grange & Lock, 2011). Many teenagers, mostly girls, eat erratically or ingest drugs (especially diet pills) to lose weight; others, mostly boys, take steroids or creatine (Calzo et al., 2015) to increase muscle mass. Both may switch from obsessive dieting, to overeating, to overexercising, and back again.

Rates of obesity are falling in childhood but increasing in adolescence and adulthood in almost every nation, including the United States. In 2001, more than 15 percent of high school students were obese in only three states (Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee). In 2013, 22 states had rates that high (MMWR, June 13, 2014).

EATING DISORDERS Obesity is an eating disorder at every age, and it is discussed in several other chapters of this book. Here we focus on three other eating disorders that appear in adolescence.

anorexia nervosa

An eating disorder characterized by self-

Anorexia nervosa is characterized by voluntary starvation. It is the extreme of what many teenage girls think about their weight: They have a distorted body image, perceiving themselves as being too heavy. Those suffering from anorexia become very underweight, risking death by organ failure. Staying thin becomes an obsession.

Although anorexia existed earlier, it was not identified until about 1950, when some high-

The rate of anorexia spikes at puberty and again in emerging adulthood. Scientists disagree about the causes—

bulimia nervosa

An eating disorder characterized by binge eating and subsequent purging, usually by induced vomiting and/or use of laxatives.

About three times as common as anorexia is bulimia nervosa (also called the binge–

Binging and purging are common among adolescents. For instance, a 2013 survey found that within the previous month 6.6 percent of U.S. high school girls and 2.2 percent of boys vomited or took laxatives to lose weight, with marked variation by state—

The third adolescent eating disorder is newly recognized in DSM-

All adolescents are vulnerable to unhealthy eating, because autonomy, anxiety, and body image can lead to disorders. Teenagers try new diets, go without food for 24 hours (as did 19 percent of U.S. high school girls in one typical month), or take diet drugs (6.6 percent) (MMWR, June 13, 2014). Parents are slow to recognize eating disorders, and they often delay in getting help (Thomson et al., 2014).

THINK CRITICALLY: Rates of eating disorders in adolescence seem to be increasing. Should parents be blamed? Why or why not?

All eating disorders—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 9.3

1. What visible changes take place in puberty?

For girls, the observable changes of puberty usually begin with nipple growth. Soon a few pubic hairs are visible, then peak growth spurt, widening of the hips, the first menstrual period (menarche), full pubic-

Question 9.4

2. How do hormones affect the physical and psychological aspects of puberty?

In girls, estrogen triggers menarche and may contribute to depression. In boys, androgens produce sperm and trigger spermarche, and, in a small number of boys, may also contribute to the onset of schizophrenia. In both boys and girls, hormones awaken their interest in sex.

Question 9.5

3. Why might some high schools adopt later start times?

A phase delay in the sleep–

Question 9.6

4. What is the connection between body fat and onset of puberty in girls and in boys?

Heavier girls reach menarche years earlier than malnourished girls do; most girls weigh at least 100 pounds before menarche. In boys, severe malnourishment always delays puberty, but body fat is not as influential.

Question 9.7

5. Why might early puberty be difficult for girls?

Early-

Question 9.8

6. What problems are common among early-

Early-

Question 9.9

7. What are the sex differences in the growth spurt?

Girls experience their height growth spurt an average of two years before boys do. Girls’ height growth spurt usually precedes menarche, whereas boys’ height growth spurt usually follows spermarche.

Question 9.10

8. How do the skin and hair change during puberty?

The skin becomes oilier, sweatier, and more acne-

Question 9.11

9. What is the difference between primary and secondary sex characteristics?

Primary sex characteristics are directly involved in reproduction, whereas secondary sex characteristics signify that the body is capable of reproduction.

Question 9.12

10. What problems might occur if adolescents do not get enough iron or calcium?

Insufficient iron can cause anemia in adolescents, restricting muscle growth and strength. Insufficient calcium can lead to osteoporosis later in life.

Question 9.13

11. Why is body image often problematic in adolescence?

Few teenagers welcome every change puberty causes in their bodies. Instead, they tend to focus on and exaggerate imperfections. Few adolescents are happy with their bodies, partly because almost none look like the bodies portrayed in the media.

Question 9.14

12. What types of disordered eating are common in adolescence?

Overeating, eating erratically, or even ingesting drugs to lose weight is common among adolescents, especially girls. Boys may also overeat or eat erratically but are more likely to take steroids, creatine, etc. to increase their muscle mass.

Question 9.15

13. What are the differences among anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating disorder?

People suffering from anorexia nervosa refuse to eat normally because their body image is severely distorted; they may believe they are too fat when actually they are dangerously underweight. Those with bulimia consume thousands of calories but then vomit or use laxatives to control their weight, whereas those with binge eating disorder overeat without purging.