Thinking, Fast and Slow

The body changes just reviewed are dramatic, but even more life-

Brain Development

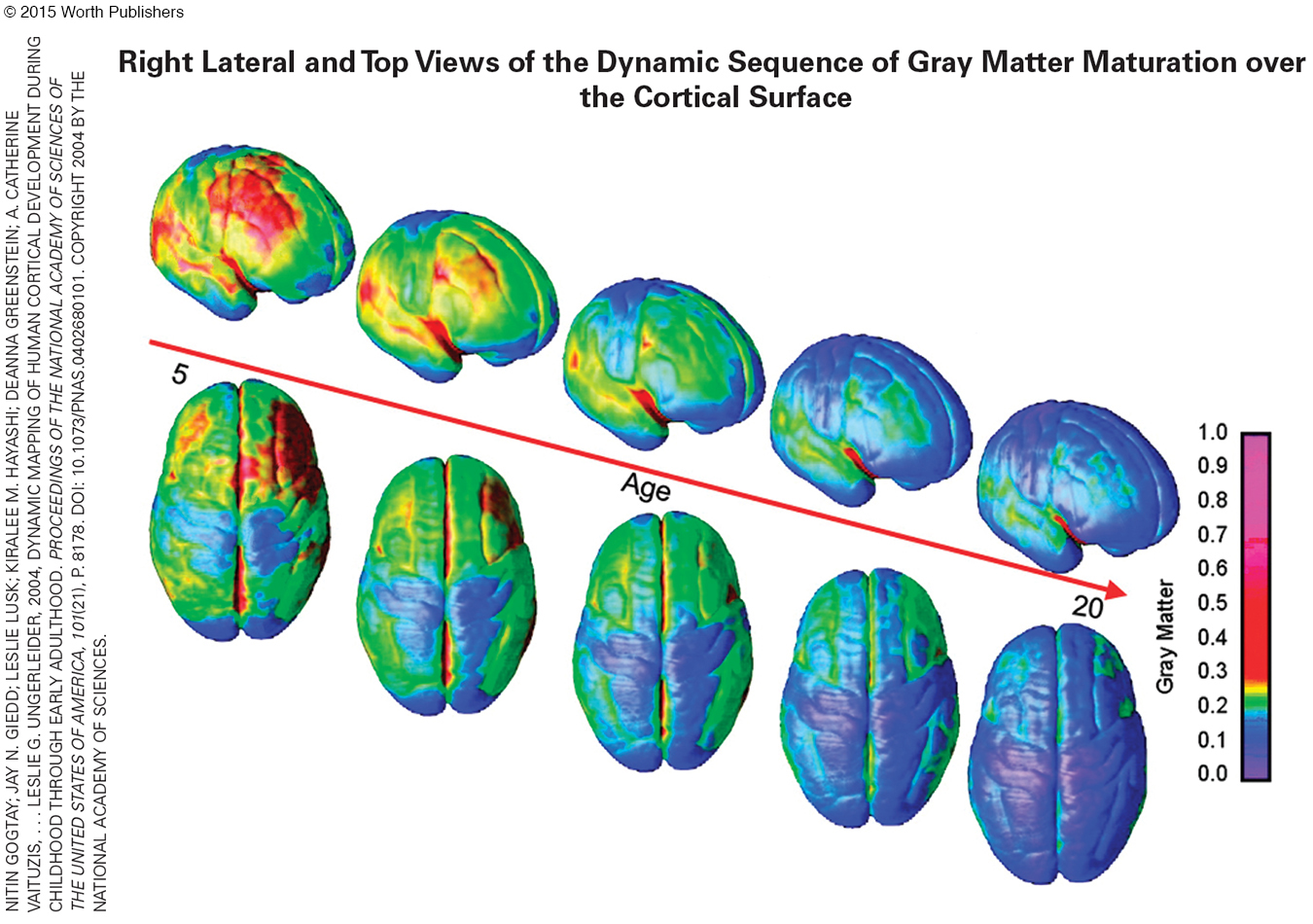

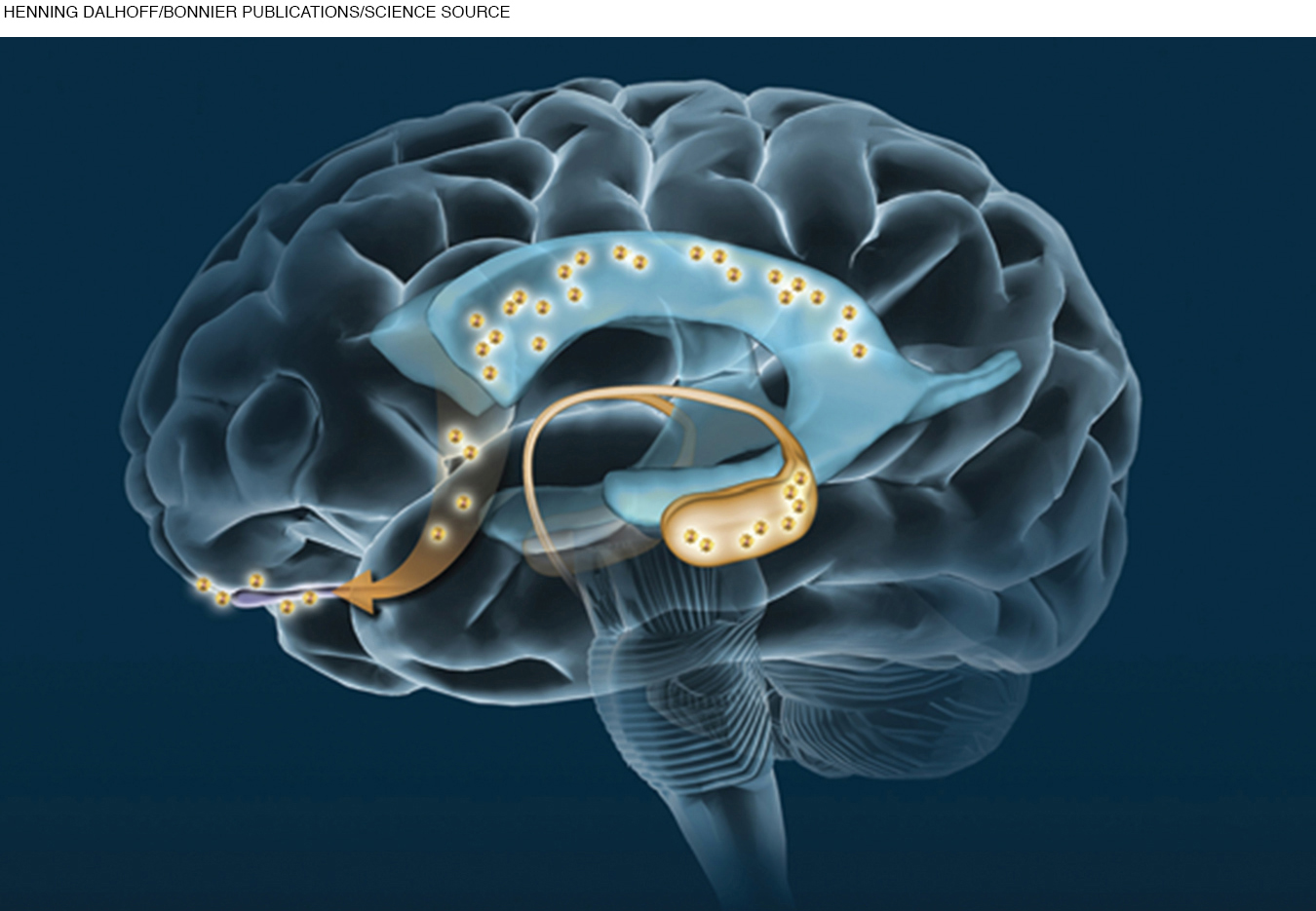

Like the rest of the body, parts of the brain grow at various rates. Myelination and maturation occur in sequence, proceeding from the lower and inner parts of the brain to the cortex, and from the back to the frontal and then the prefrontal cortex (Sowell et al., 2007). That means that the limbic system (site of fear and anxiety) matures before regions where planning, emotional regulation, and impulse control occur (see Figure 9.3).

Furthermore, hormones directly target the amygdala (a key component of the limbic system) (Romeo, 2013), but full functioning of the cortex requires time more than hormones, which means that the prefrontal cortex is not mature until years of experience beyond the teen years.

Video Activity: Brain Development: Adolescence features animations and illustrations of the changes that occur in the teenage brain.

This developmental mismatch is a particular problem in the twenty-

Teens seek excitement and pleasure, especially the joy of a peer’s admiration (Galván, 2013). In fact, when others are watching, teens find it thrilling to take daredevil risks that produce social acclaim (Albert et al., 2013). Especially when they are with friends, the thrill of new experiences and sensations can overpower the caution that their parents have tried to instill. Fatal car accidents, with many passengers, are one result.

The normal sequence of brain maturation (limbic system at puberty, prefrontal cortex sometime in the early 20s) combined with the earlier onset of puberty means that, for contemporary teenagers, emotions rule behavior for a decade.

When stress, arousal, passion, sensory bombardment, drug intoxication, or depri-

The parts of the brain dedicated to analysis are immature until long after the first hormonal rushes and sexual urges. Sadly, teenagers have access to fast cars, lethal weapons, and dangerous drugs before their brains are mature. My friend said to his neighbor, who gave his son a red convertible for high school graduation, “Why didn’t you just give him a loaded gun?” The mother of the 20-

A more common example comes from teens sending text messages while they are driving. In one survey, among U.S. high school seniors who have their driver’s license, 60 percent texted while driving within the past month, although that is illegal almost everywhere (MMWR, June 13, 2014). More generally, despite quick reflexes and better vision, far more teenagers die in motor-

Any decision, from whether to eat a peach to where to go to college, requires balancing risk and reward, caution and attraction. Experiences, memories, emotions, and the prefrontal cortex help people choose to avoid some actions and perform others. Since the reward parts of adolescents’ brains are stronger than the inhibition parts (Luna et al., 2013), many adolescents act in ways that seem foolhardy to adults.

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

The Pleasures of the Adolescent Brain

Some risk-

When peers are watching, the adolescent brain’s pleasure at a risky win apparently outweighs the brain’s disappointment at a risky loss. This is demonstrated with simulated driving, when a teen is at the wheel (on a computer) with two friends nearby, and a traffic light turns from green to yellow. Teens—

The joy of beating the light activates the pleasure centers of their brains, and failure—

That this peer effect involves brain pleasure, rather than merely response to the encouragement of friends, was shown in another study. Gambling choices with known odds were presented to 15-

When the odds were good, almost all the teens gambled, no matter whether they thought a peer was watching or not. But when odds of a loss outnumbered those of a win by 2:1, 40 percent nonetheless took the chance when a peer was watching. Only 15 percent did so without the observer.

The researchers suggest that when a peer observes, the pleasure centers in the brain are most strongly activated when the odds are against success. This is discouraging to any adult who thinks that warning a teenager about the likelihood of HIV/AIDS, addiction, or death will stop risk taking: Greater risk may lead to greater pleasure.

This study had only 52 participants. Indeed, most such experiments involve relatively few participants, in part because brain scans are expensive. As you remember from Chapter 1, scientists often use other methods to confirm results found in one type of study. That has happened with this research.

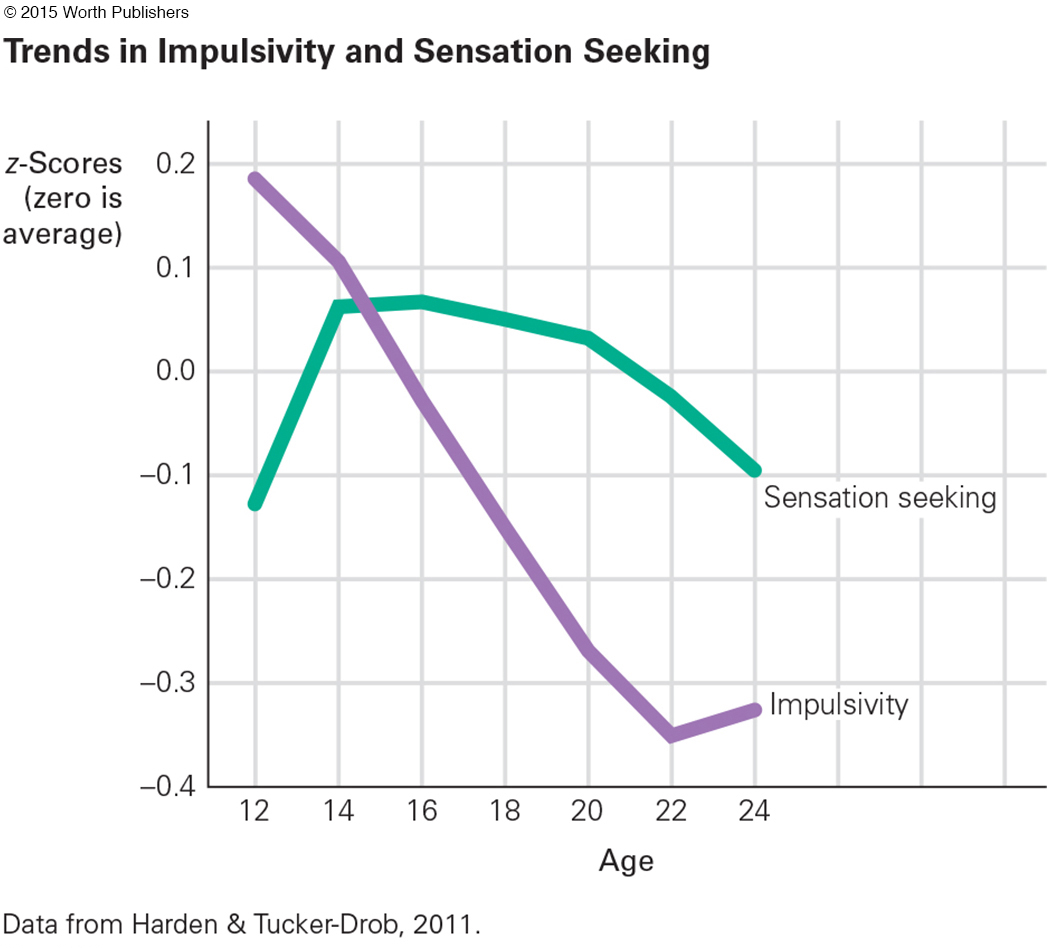

One longitudinal survey of more than 7,000 adolescents, from age 12 through age 24, assessed their ideas, activities, and plans (Harden & Tucker-

On average, sensation seeking accelerated rapidly at puberty, and both sensation seeking and impulsivity slowly declined with maturation. However, trajectories varied individually: Sensation seeking did not necessarily correlate with impulsivity. Thus, the limbic system was not necessarily linked to the prefrontal cortex (Harden & Tucker-

The results were “consistent with neurobiological research indicating that cortical regions involved in impulse control and planning continue to mature through early adulthood . . . [and that] subcortical regions that respond to emotion, novelty, and reward are more responsive in middle adolescence than in either children or adults” (Harden & Tucker-

The same idea is presented in the diagram. Two experts in cognitive development (Duckworth & Steinberg, 2015) agree that impulse control (the prefrontal cortex) continues to mature throughout childhood and adolescence. The problem is that sensation seeking suddenly escalates at puberty, temporarily outstripping growth of the parts of the brain that keep emotional impulses in check.

What can be concluded from all the brain science on adolescents? Young brains do not react as older ones do. As with adventuresome toddlers (the “little scientists”) who might run toward exploration and danger, the admirable curiosity and bravery of the young human is a path toward learning as well as pleasure. Adults must ensure that adventure leads to wisdom, not harm.

BENEFITS OF ADOLESCENT BRAIN DEVELOPMENT It is easy for adults to be critical of adolescent behavior and blame it on hormones, peers, culture, or the latest chosen culprit, brains. Exaggerated metaphors have changed from blaming puberty as the cause of “storm and stress” to blaming brains for “all gas and no brakes” (Payne, 2012).

Yet remember that difference is not always deficit. Gains as well as losses are part of every developmental period, and continuity from one life period to another is evident even as each stage includes specific problems. What might be the benefits of the adolescent brain?

Increasing myelination and slower inhibition allows lightning fast reactions, making adolescent athletes quick and fearless as they steal a base, tackle a fullback, or sprint when their lungs feel about to burst. Ideally, coaches channel such bravery.

Furthermore, as the brain’s reward areas activate positive neurotransmitters, teenagers become happy. A new love, a first job, a college acceptance, or even an A on a term paper can produce a rush of joy, to be remembered and cherished lifelong.

Teenagers need to take risks and learn new things, because “[t]he fundamental task of adolescence—

Synaptic growth enhances moral development as well. Adolescents question their elders and forge their own standards. This is an asset if adolescent values are less self-

THINK CRITICALLY: Given the nature of adolescent brain development, how should society respond to adolescent thoughts and actions?

Thus, the developing prefrontal cortex “confers benefits as well as risks. It helps explain the creativity of adolescence and early adulthood, before the brain becomes set in its ways” (Monastersky, 2007, p. A17). The emotional intensity of adolescents “intertwines with the highest levels of human endeavor: passion for ideas and ideals, passion for beauty, passion to create music and art” (Dahl, 2004, p. 21).

Formal Operational Thought

formal operational thought

In Piaget’s theory, the fourth and final stage of cognitive development, characterized by systematic logical thinking and by understanding abstractions.

Adolescents move past concrete operational thinking (discussed in Chapter 7) and consider abstractions. Jean Piaget described a shift to formal operational thought, including “assumptions that have no necessary relation to reality” (Piaget, 1950/2010, p. 148).

EGOCENTRISM For many adolescents, the first step toward abstract thought is very personal, although unrealistic, thought. They think deeply about themselves. One reason adolescents spend so much time talking on the phone, e-

adolescent egocentrism

A characteristic of adolescent thinking that leads young people to believe in their own uniqueness, and to imagine that other people are also focused on them.

They also imagine what others—

Egocentrism leads adolescents to interpret everyone else’s behavior as if it were a judgment on them. A stranger’s frown or a teacher’s critique could make a teenager conclude that “No one likes me” and then deduce that “I am unlovable” or even claim that “I can’t leave the house.”

More positive casual reactions—

personal fable

The belief that one’s own emotions, experiences, and destiny are unique, more wonderful or awful than anyone else’s.

invincibility fable

The fantasy that a person cannot be harmed by anything that might defeat a normal mortal, such as unprotected sex, drug abuse, or high-

Several aspects of adolescent egocentrism are named, among them the personal fable and the invincibility fable, which often appear together (Alberts et al., 2007). The personal fable is the belief that one is unique, destined to have a heroic, fabled, legendary life. Some 12-

Some adolescents see no contradiction between the personal fable and invincibility. Some believe that they will not be hurt by fast driving, unprotected sex, or addictive drugs unless fate wills it. If they survive unscathed from a dangerous risk, they may feel invincible, not relieved; special, not unlucky.

imaginary audience

The other people who, in an adolescent’s egocentric belief, watch his or her appearance, ideas, and behavior.

Egocentrism creates an imaginary audience in the minds of many adolescents. They believe they are at center stage, with all eyes on them, and they imagine how others might react to their appearance and behavior.

The imaginary audience can cause teenagers to enter a crowded room as if they are the most attractive human beings alive. They might put studs in their lips or blast music for all to hear, calling attention to themselves. The reverse is sometimes evident: Many a 12-

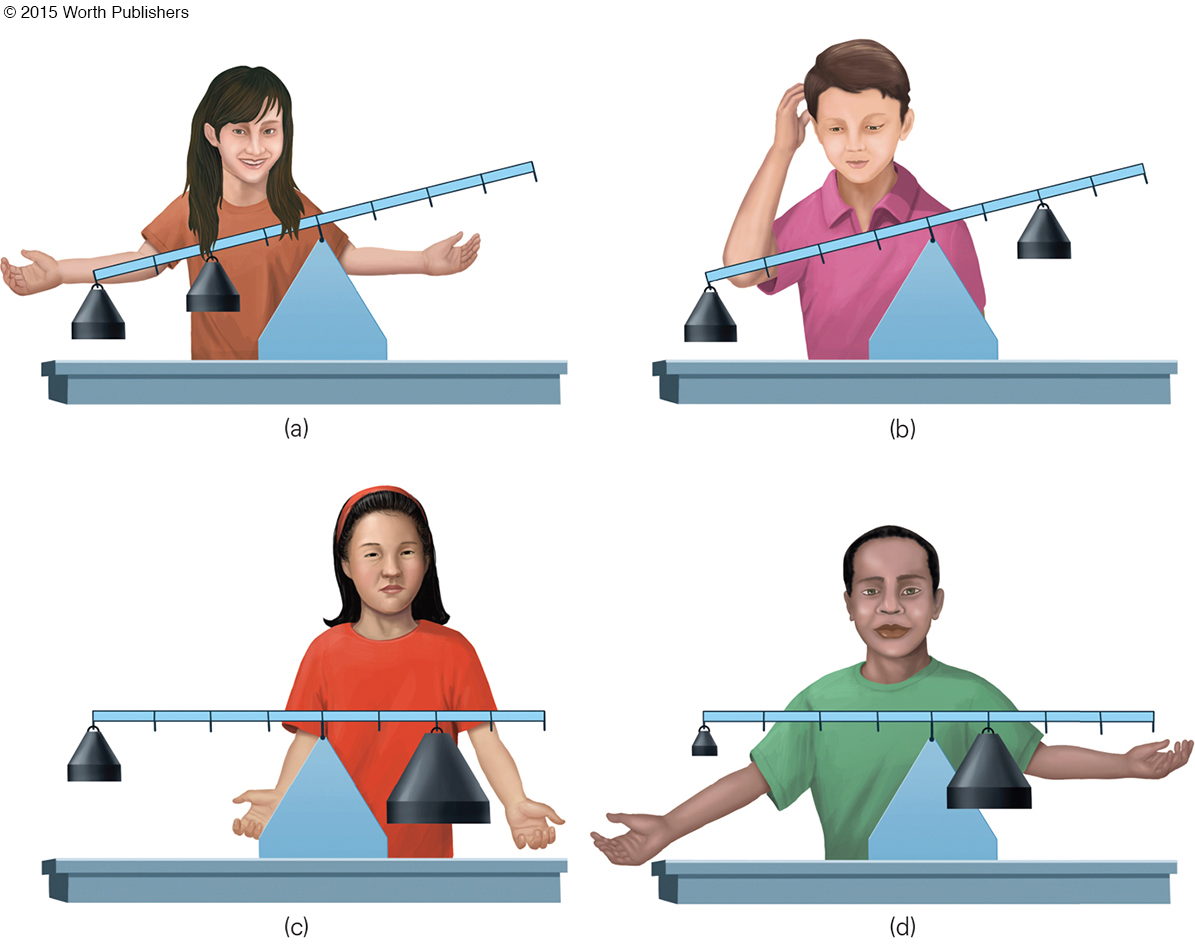

PIAGET’S EXPERIMENTS Egocentrism can coexist with more logical and abstract intelligence. Piaget and his colleagues devised tasks to assess formal operational thought (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958/2013b).

In one experiment (diagrammed in Figure 9.5), children of many ages balance a scale by hooking weights onto the scale’s arms. To master this task, they must realize that the weights’ heaviness and distance from the center interact reciprocally to affect balance.

The concept of balancing was completely beyond the 3-

By age 10, children thought about location but used trial and error, not logic. Finally, by about age 13 or 14, some children hypothesized and tested the reciprocal relationship between weight and distance and developed the correct formula (Piaget & Inhelder, 1972).

In balancing, as in all of Piaget’s experiments, “in contrast to concrete operational children, formal operational adolescents imagine all possible determinants . . . [and] systematically vary the factors one by one, observe the results correctly, keep track of the results, and draw the appropriate conclusions” (P. Miller, 2011, p. 57).

Video Activity: The Balance Scale Task shows children of various ages completing the task and gives you an opportunity to try it as well.

HYPOTHETICAL-

The adolescent . . . thinks beyond the present and forms theories about everything, delighting especially in considerations of that which is not. . . .

[Piaget, 1950/2010, p. 147]

hypothetical thought

Reasoning that includes propositions and possibilities that do not reflect reality.

Adolescents are primed to engage in hypothetical thought, reasoning about if–

If all mammals can walk,

And whales are mammals,

Can whales walk?

Younger adolescents often answer “No!” They know that whales swim, not walk, so the logic escapes them. Some adolescents answer “Yes.” They understand if.

Possibility no longer appears merely as an extension of an empirical situation or of actions actually performed. Instead, it is reality that is now secondary to possibility.

[Inhelder & Piaget, 1958/2013b, p. 251; emphasis in original]

Because of this new ability, many adolescents sharply criticize their parents, their school, their society. They “naively underestimate the practical problems involved in achieving an ideal future for themselves or for society” (P. Miller, 2011, p. 59). Why doesn’t everyone get good health care; why don’t the Palestinians and Israelis agree; why doesn’t the teacher realize that my question is brilliant; why doesn’t Dad let me stay out past midnight?

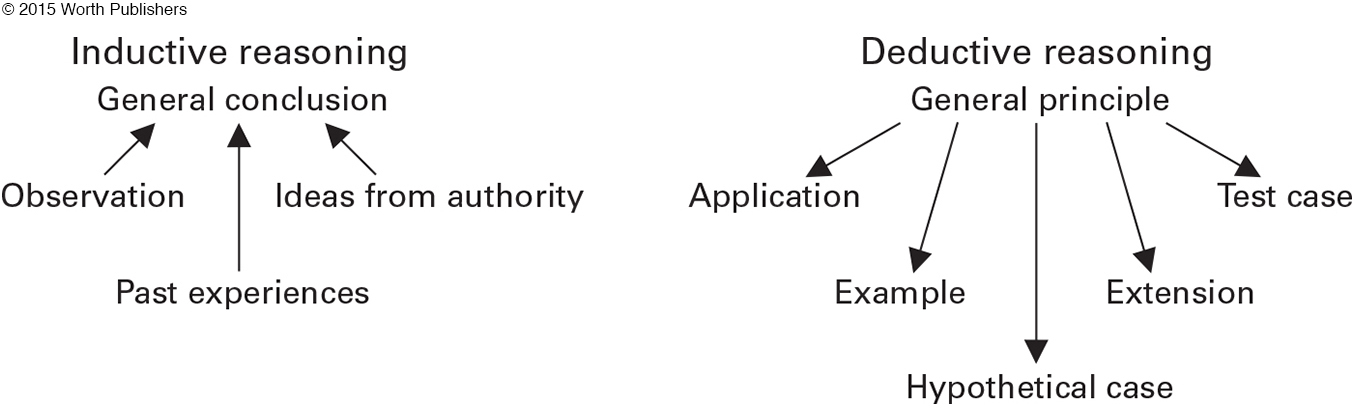

deductive reasoning

Reasoning from a general statement, premise, or principle, through logical steps, to figure out (deduce) specifics. (Also called top-

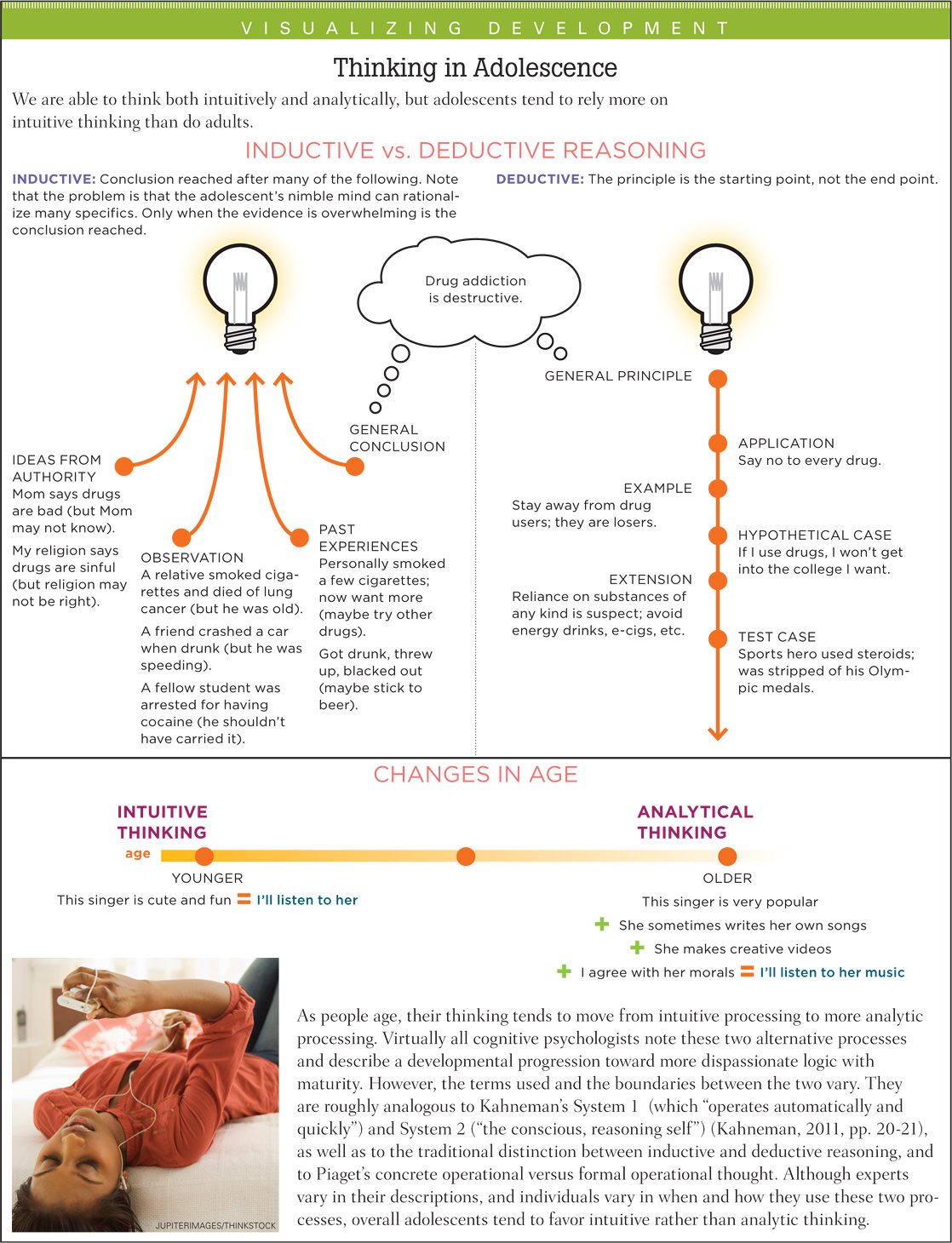

In developing the capacity to think hypothetically, adolescents gradually become capable of deductive reasoning, or top-

inductive reasoning

Reasoning from specific experiences or facts to reach (induce) a general conclusion. (Also called bottom-

By contrast, during the primary school years, children accumulate facts and personal experiences (the knowledge base), asking what and why. The result is inductive reasoning, or bottom-

One example of moving past personal experience in reasoning ability is the understanding of prejudice. Almost every adolescent knows that racism exists—

By contrast, adolescents begin to think, deductively, that policy solutions need to attack racism. That is formal operational thinking.

This interpretation arises from a study of adolescent agreement or disagreement with policies to reduce racial discrimination (Hughes & Bigler, 2011). Not surprisingly, most students in an interracial U.S. high school recognized disparities between African and European Americans and believed that racism was a major cause. What was surprising to the researchers is that age made a difference.

Among those who were aware of marked inequalities, more older adolescents (age 16 to 17) supported systemic solutions (e.g., affirmative action and desegregation) than did younger adolescents (age 14 to 15). The researchers wrote: “during adolescence, cognitive development facilitates the understanding that discrimination exists at the social-

In thinking about race and many other issues, neither adolescents nor adults necessarily reason at the formal operational level. Piaget probably overestimated the prevalence of this fourth period of intelligence. As now discussed, many contemporary scholars believe there are two modes of thinking, and that most people, most of the time, do not use formal operational thought (Barrouillet, 2011).

Two Modes of Thinking

dual-

The idea that two modes of thinking exist within the human brain, one for intuitive emotional responses and one for analytical reasoning.

Advanced logic in adolescence is counterbalanced by the increasing power of intuitive thinking. A dual-

INTUITION VERSUS ANALYSIS Cognitive psychologists use various terms for and descriptions of two modes of human cognition (Evans & Stanovich, 2013). The terms include: intuitive/analytic, implicit/explicit, creative/factual, contextualized/decontextualized, unconscious/conscious, gist/quantitative, emotional/intellectual, experiential/rational, personal/impersonal, hot/cold, systems 1 and 2. Although these two modes interact and can overlap, each mode is distinct (Kuhn, 2013).

Question 9.16

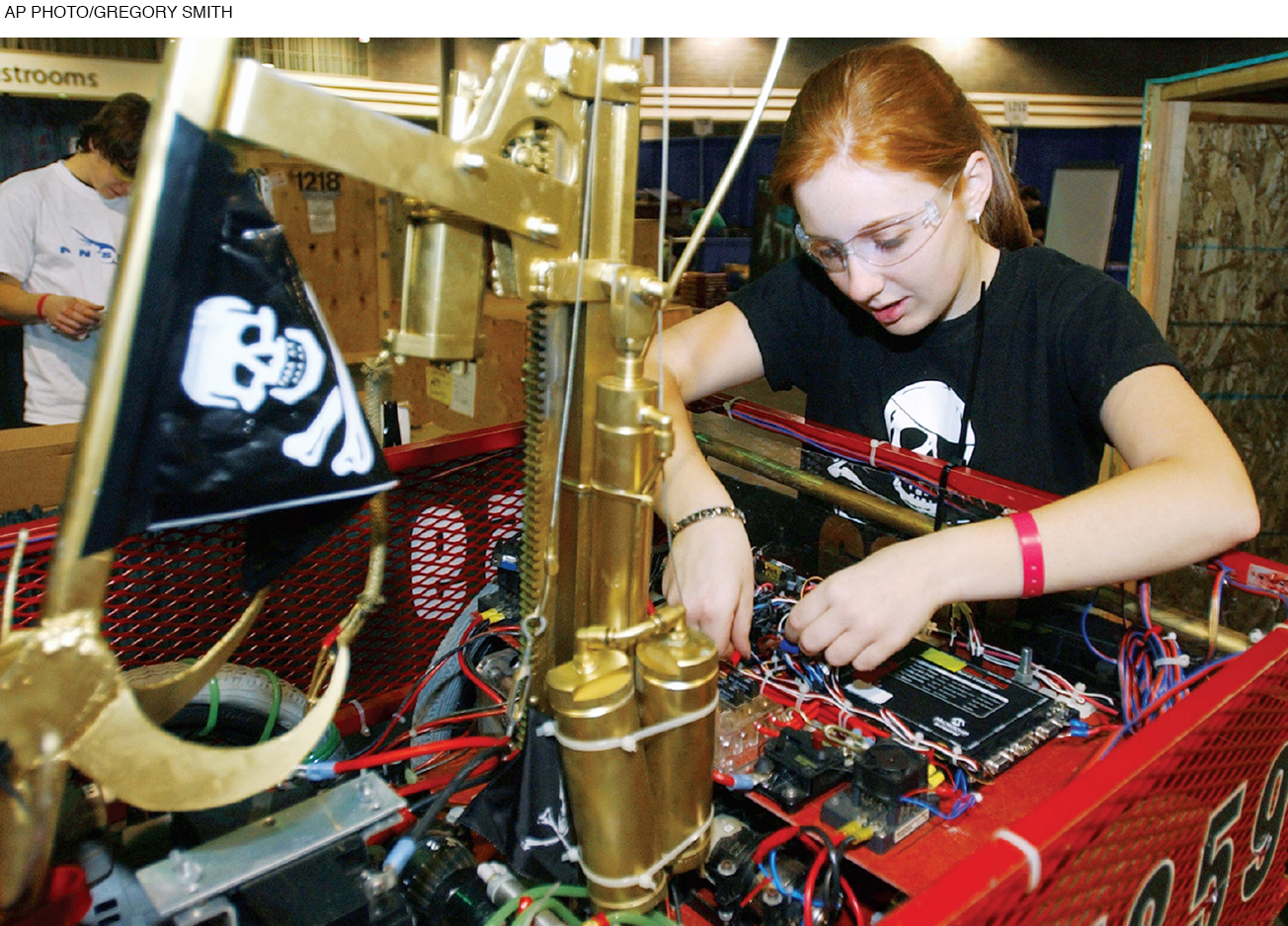

OBSERVATION QUIZ

Melissa seems to working by herself, but what sign do you see that suggests she is part of a team who built this robot?

The flag on the robot matches her T-

In describing adolescent cognition, here we use the terms intuitive and analytic.

intuitive thought

Thought that arises from an emotion or a hunch, a “gut feeling” influenced by past experiences and cultural assumptions.

Intuitive thought begins with a belief, assumption, or general rule (called a heuristic) rather than logic. Intuition is quick and powerful; it feels “right.”

analytic thought

Thought that results from analysis, such as a systematic exploration of pros and cons, risks and consequences, possibilities and facts. Analytic thought depends on logic and rationality.

Analytic thought is the formal, logical, hypothetical-

deductive thinking described by Piaget. It involves rational analysis of many factors whose interactions must be calculated, as in the scale- balancing problem.

The thinking described by the first half of each pair is easier and quicker, preferred in everyday life. We are all “predictably irrational” at times (Ariely, 2009). Sometimes, however, the second mode is needed, when deeper thought is demanded.

The discrepancy between the maturation of the limbic system and of the prefrontal cortex tilts adolescents toward the more emotional, personal, experiential mode. Adolescents tend to be “fast and furious” intuitive thinkers, unlike their teachers and parents, who prefer slower, more analytic thinking.

Experiences and role models influence choices, not only in deciding what to do but also in choosing which intellectual process to use in making a decision. Conversations, observations, and debate all advance cognition and lead to a deeper consideration of the facts (Kuhn, 2013). As they grow older, adolescents sometimes gain in logic and sometimes regress; the social context and training in statistics are major influences on adolescent cognition (Klaczynski & Felmban, 2014).

To test yourself on intuition and analysis, answer the following three problems:

Question 9.17

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

Intuitive Analytic 10 cents 5 cents Question 9.18

If it takes 5 minutes for 5 machines to make 5 widgets, how long would it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets?

Intuitive Analytic 100 minutes 5 minutes Question 9.19

In a lake, there is a patch of lily pads. Every day the patch doubles in size. If it takes 48 days for the patch to cover the entire lake, how long would it take for the patch to cover half the lake?

Intuitive Analytic 24 days 47 days

[From Gervais & Norenzayan, 2012]

Although many researchers find that logic gradually overcomes biased reasoning during adolescence, whether or not such analysis is used depends on specifics. One instance when being older did not improve logic occurred when adolescents were asked to decide how likely a hypothetical girl named Jennifer, described as lazy and not well liked, was to be obese. Among those teenagers who idealized thinness, the older ones more often jumped to the illogical conclusion that Jennifer was probably obese (Klaczynski & Felmban, 2014).

In dozens of studies, being smarter as measured by an intelligence test does not advance logic as much as having more experience, in school and in life. Students can learn to use statistics and to respect expert opinion, and that helps them think more rationally—

A CASE TO STUDY

“What Were You Thinking?”

Laurence Steinberg is a noted expert on adolescence (e.g., Steinberg, 2014). He is also a father.

When my son, Benjamin, was 14, he and three of his friends decided to sneak out of the house where they were spending the night and visit one of their girlfriends at around two in the morning. When they arrived at the girl’s house, they positioned themselves under her bedroom window, threw pebbles against her windowpanes, and tried to scale the side of the house. Modern technology, unfortunately, has made it harder to play Romeo these days. The boys set off the house’s burglar alarm, which activated a siren and simultaneously sent a direct notification to the local police station, which dispatched a patrol car. When the siren went off, the boys ran down the street and right smack into the police car, which was heading to the girl’s home. Instead of stopping and explaining their activity, Ben and his friends scattered and ran off in different directions through the neighborhood.

. . . After his near brush with the local police, Ben had returned to the house out of which he had snuck, where he slept soundly until I awakened him with an angry telephone call, telling him to gather his clothes and wait for me in front of his friend’s house. On our drive home, after delivering a long lecture about what he had done and about the dangers of running from armed police in the dark when they believe they may have interrupted a burglary, I paused.

“What were you thinking?” I asked.

“That’s the problem, Dad,” Ben replied, “I wasn’t.”

[Steinberg, 2004, pp. 51, 52]

Steinberg realized that his son was right: When emotions are intense, especially when friends are nearby, the logical part of the brain shuts down. This shutdown is not reflected in questionnaires that require teenagers to respond to paper-

the prospect of visiting a hypothetical girl from class cannot possibly carry the excitement about the possibility of surprising someone you have a crush on with a visit in the middle of the night. It is easier to put on a hypothetical condom during an act of hypothetical sex than it is to put on a real one when one is in the throes of passion . . . It is easier to just say no to a hypothetical beer than it is to a cold frosty one on a summer night.

[Steinberg, 2004, p. 53]

Ben reached adulthood safely. Some other non-

PREFERRING EMOTIONS Why do high school students, well aware of the logic of the science, sometimes not use formal operational thinking? Dozens of experiments and extensive theorizing have found some answers (Albert & Steinberg, 2011).

Essentially, analysis is more difficult than intuition. It requires questioning ideas that are comforting and familiar. Once people of any age reach an emotional conclusion (sometimes called a “gut feeling”), they resist changing their minds.

Furthermore, weighing alternatives and thinking of possibilities can be paralyzing. The systematic, analytic thought that Piaget called formal operational is slow and costly, not fast and frugal, wasting precious time when a young person wants to act.

One characteristic of adolescents—

It is helpful to realize that, even when they are analytical, teenagers might analyze a situation and reach a conclusion other than the one their parents would. A 15-

THINK CRITICALLY: When might an emotional response to a problem be better than an analytic one?

More generally, adults want adolescents to take care of their health, which means avoiding cigarettes, junk food, and promiscuity. But emotional thinking pushes in the opposite direction, and some analytic arguments (about the risk of cancer, for instance) are dismissed (Gibbons et al., 2012a). That is why effective messages to halt teen smoking discuss smelly breath, stained fingers, and yellow teeth.

Digital Natives

Adults over age 40 grew up without the Internet, instant messaging, Twitter, Snapchat, blogs, cell phones, smartphones, MP3 players, tablets, or digital cameras. In contrast, today’s teenagers have been called digital natives, although if that term implies that they know everything about digital communication, it is a misnomer (boyd, 2014).

A huge gap between those with and without computers was bemoaned a decade ago; it divided boys from girls and rich from poor (Dijk, 2005; Norris, 2001). Now that digital divide is shrinking, and a new one is evident, between the old and the young.

As costs tumble, the smartphone has been particularly important among low-

TECHNOLOGY AND COGNITION In general, educators accept, even welcome, students’ facility with technology. There are “virtual” schools in which students earn all their credits online, never entering a school building, and in several school districts all the students have tablets.

Video: The Impact of the Media on Adolescent Development

Remember that research before the technology explosion found that direct instruction, practice, conversation, and experience advance adolescent thought. Social networking via technology may speed up this process, as teens communicate daily with dozens—

Most secondary students check facts, read explanations, view videos, and thus grasp concepts they would not have understood without technology. For some adolescents, the Internet is their only source of information about health and sex. Almost every high school student in the United States uses the Internet for research, finding it quicker and more extensive than books on library shelves.

Educators claim that the most difficult aspect of technology is teaching students how to evaluate sources, some reputable, some nonsensical. To this end, teachers explain the significance of .com, .org, .edu, and .gov (O’Hanlon, 2013).

ABUSE AND ADDICTION? Parents worry about sexual abuse via the Internet. Research is reassuring: Although sexual predators lurk online, most teens never encounter them. Sexual abuse is a serious problem, but if sexual abuse is defined as a perverted older stranger taking advantage of an innocent teenager met online, it is “extremely rare” (Mitchell et al., 2013, p. 1226).

The data show that the percent of teenagers who say that someone online tried to get them to talk about sex declined since 2000 from 10 to 1. Those 1 percent were almost always solicited by another young person whom the teenager already knew—

For some adolescents, chat rooms, video games, and Internet gambling may be considered addictive, taking time from active play, schoolwork, and friendship. Internet addiction is considered a problem in many nations (Tang et al., 2014; Y–

However, some scholars worry that adults tend to pathologize normal teen behavior, particularly in China, where rehabilitation centers are strict—

The North American psychiatrists who wrote the new DSM-

cyberbullying

Bullying that occurs when one person attacks and harms another via technology (e.g., e-

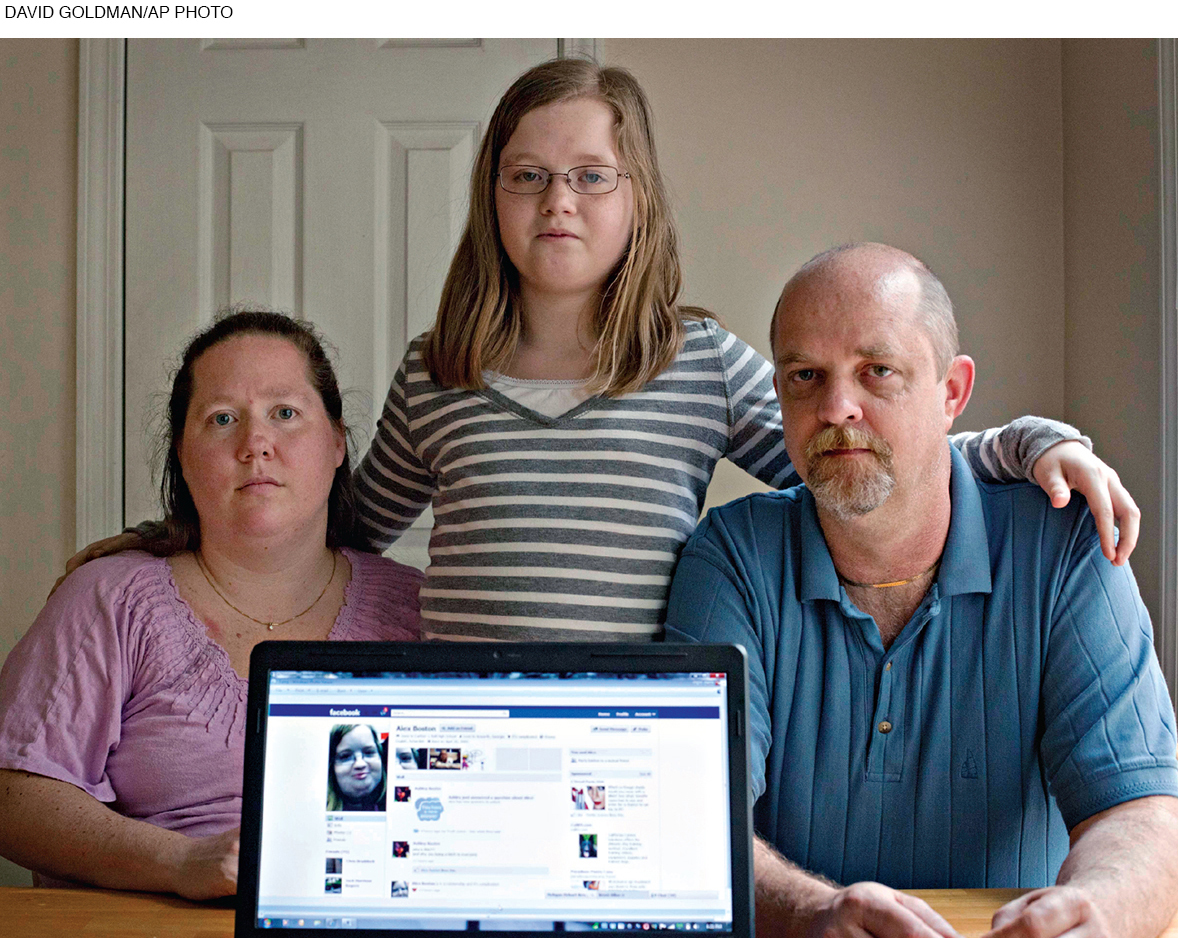

CYBER DANGER When a person is bullied via electronic devices, usually via social media, text messages, or smartphone videos, that is cyberbullying. The adolescents involved in cyberbullying are usually already bullies or victims or both, with bully-

Texted and posted rumors and insults can “go viral,” reaching thousands, transmitted day and night. Some adolescents take videos of others drunk, naked, or crying and send them to dozens of others, who may send them to yet others, who may post them on YouTube or Vine. Since young adolescents are impulsive and low on judgment, cyberbullying is particularly prevalent and cruel between ages 11 and 14.

Although the causes of all forms of bullying are similar, each form has its own sting. Cyberbullying is most harmful if the victim believes in the imaginary audience, if sexual impulses are new, and if impulsive thoughts precede analytic ones. All that means that young adolescent victims of cyberbullying are likely to suffer from depression, even suicide (Bonanno & Hymel, 2013).

The vulnerability of adolescence was tragically evident for a California 15-

One aspect of this tragedy will come as no surprise to adolescents: sexting, as sending sexual photographs is called. As many as 30 percent of adolescents report having received sext photos. Many teens send their own sexy “selfies” and are happy to receive sext messages (Temple et al., 2014). As with Internet addiction, researchers have yet to agree on how to measure sexting or how harmful it is.

There are two dangers: (1) Pictures may be forwarded without the person’s knowledge, and (2) those who send erotic self-

The danger of all forms of technology lies not in the equipment but in the cognition of the user. That is the conclusion of a national survey which found that 7 percent of all teens willingly sent sext photos of themselves, yet sexting correlated with risky sex, depression, and low self-

As is true of many aspects of adolescence (puberty, eating disorders, brain development, egocentric thought, use of contraception, and so on), context, adults, peers, and the adolescent’s own personality and temperament “shape, mediate, and/or modify effects” of technology (Oakes, 2009, p. 1142).

One careful observer claims that instead of being native users of technology, many teenagers are naive users—

THINK CRITICALLY: The older people are, the more likely they are to be critical of social media. Is that wisdom or ignorance? Why?

Educators can help with all this—

WHAT HAVE YOU LEARNED?

Question 9.20

1. Why does the limbic system develop before the prefrontal cortex?

This happens because myelination and maturation begin in the lower and inner parts of the brain to the cortex, and from the back to the frontal cortex and then the prefrontal cortex. Hormones also play a part: they have a much greater affect on the amygdala than on the prefrontal cortex, which needs time to mature.

Question 9.21

2. How might seeking sensations lead an adolescent to trouble?

Because the frontal lobe is still maturing, emotions rule adolescent behavior and impulsivity reigns relatively unchecked by logical thought. Adolescents take risks, such as driving fast and texting while they are driving. Thoughtless impulses and poor decisions are almost always to blame when teenagers die in motor-

Question 9.22

3. What are some of the benefits of adolescent brain function?

(1) Faster reaction time; (2) increased positive emotions; (3) easier acquisition of new ideas; (4) enhanced moral development; and 5) willingness to question tradition and try new things.

Question 9.23

4. How does adolescent egocentrism differ from early-

In early childhood, egocentrism refers to the inability to take another person’s perspective. Young adolescents not only think intensely about themselves but also think about what others think of them. Adolescents regard themselves as unique, special, and much more socially significant than they actually are.

Question 9.24

5. What perceptions arise from belief in the imaginary audience?

Adolescents believe that everyone is watching them, which makes them very self-

Question 9.25

6. What are the characteristics of formal operational thinking?

As concrete operational thinkers, children draw conclusions on the basis of their own experiences and what they have been told. Formal operational adolescents imagine all possible determinants and systematically vary the factors one by one, observe the results, keep track of the results, and draw the appropriate conclusions. Formal operational thinking enables systematic, logical thinking as well as the ability to understand and manipulate abstract concepts. Teens become capable of deductive reasoning and hypothetical thinking.

Question 9.26

7. What is the difference between inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning?

In inductive reasoning (which is more likely to be used by children), many specific examples lead to a general conclusion. In deductive reasoning (of which adolescents are more capable), an abstract idea or premise is the starting point, and then logic is employed to draw a specific conclusion. Inductive reasoning is quick and automatic, but also more prone to error than deductive reasoning.

Question 9.27

8. When might intuition and analysis lead to opposite conclusions?

Intuition begins with a belief, assumption, or general rule. It is quick and powerful—

Question 9.28

9. Why do most people prefer intuitive thinking, not analytic thought?

People tend to use intuition in their everyday lives because it is faster and easier to rely on preexisting beliefs, assumptions, and rules than it is to reason deliberately.

Question 9.29

10. What benefits come from adolescents’ use of technology?

Research conducted before the technology explosion found that with education, conversation, and experience, adolescents move past egocentric thought. Social networking may speed up this process, as teens communicate daily with dozens of friends via e-

Question 9.30

11. What problems do adults fear from teenage use of the Internet?

Parents worry that their teenagers will be victimized by online sexual predators, even though in reality this is quite rare. They may also fear more likely dangers—

Question 9.31

12. Why is cyberbullying particularly harmful during adolescence?

Adolescents, especially those between ages 11 and 14, are often impulsive and low on judgment and believe in the imaginary audience. Consequently, they are more vulnerable to depression and suicide if they are victims of cyberbullying.

Question 9.32

13. Why might sexting be a problem?

(1) Pictures might be forwarded without the person’s knowledge, and (2) those who send erotic self-

Question 9.33

14. How is the term digital native misleading?

The term “native” implies that adolescents are adept with technology, whereas many are actually naive—they believe Web sites have privacy settings that do not exist or trust sites that are biased or misleading.