A Healthy Time

A Healthy Time

middle childhood The period between early childhood and early adolescence, approximately from ages 6 to 11.

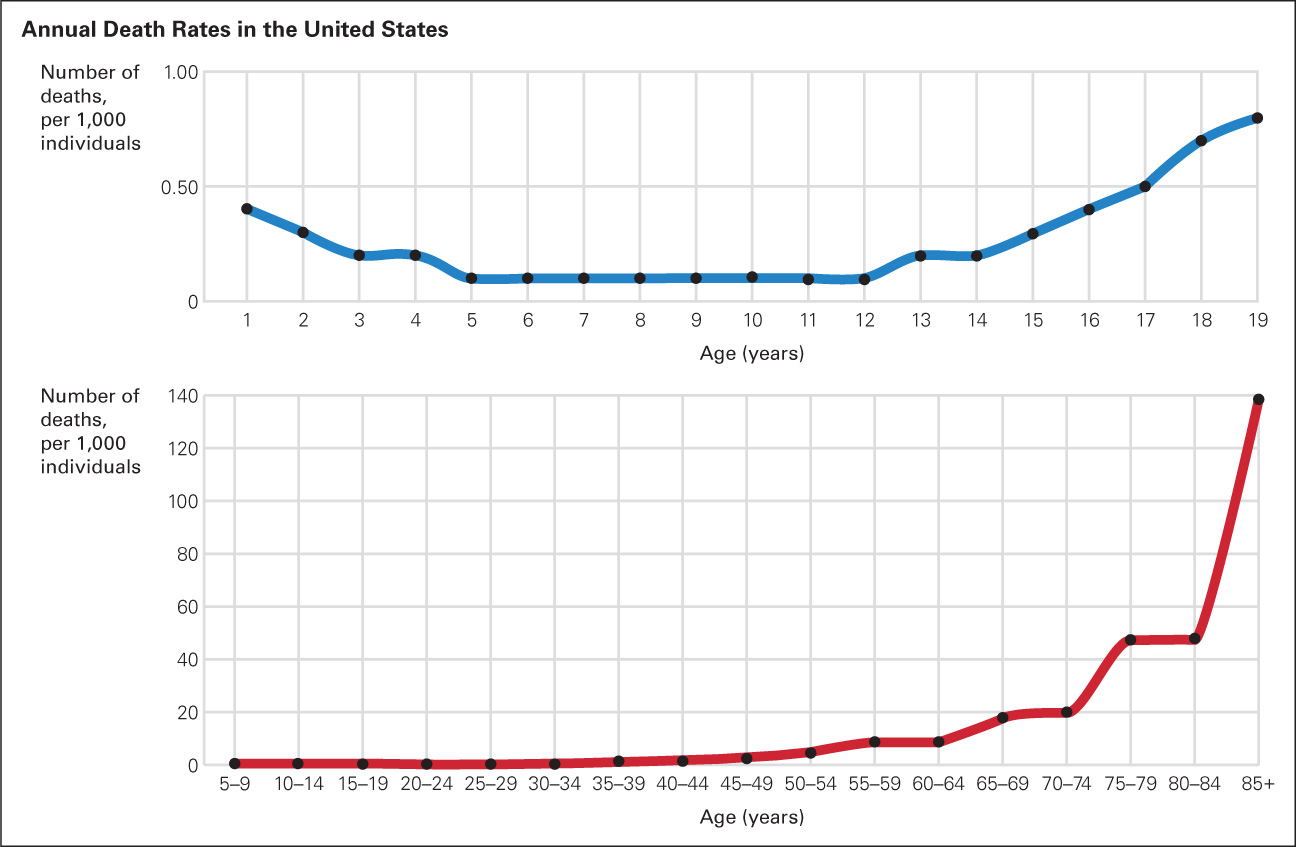

Genes and environment safeguard middle childhood, as the years from about 6 to 11 are called (Konner, 2010). Fatal diseases or accidents are rare; both nature and nurture make these years the healthiest of the entire life span (see Figure 11.1).

Observation Quiz From the bottom graph, it looks as if ages 9 and 19 are equally healthy, but they are dramatically different in the top graph. What is the explanation for this?

Answer to Observation Quiz: Look at the vertical axes. From age 1 to 20, the annual death rate is less than 1 in 1,000.

FIGURE 11.1

Death at an Early Age? Almost Never! Schoolchildren are remarkably hardy, as measured in many ways. These charts show that death rates for 6-Genetic diseases are more threatening in early infancy or old age than in middle childhood, and serious accidents and fatal illnesses are less common, even compared with a few decades ago. This is true virtually everywhere. For example, in the United States in 1950 the death rate per 100,000 children aged 5 to 14 was 70; in 2010, it was 13. Even the incidence of minor illnesses, such as ear infections, infected tonsils, and flu, has been reduced, in part because of better medicine and immunization (National Center for Health Statistics, 2013)

Slower Growth, Greater Strength

Unlike infants or adolescents, school-

Teeth

Important to the individual child is the loss of baby teeth, with the entire set replaced by permanent teeth beginning at about age 6 (with girls a few months ahead of boys) and complete by puberty.

Important to society is oral health overall. Sixty years ago, many children neither brushed their teeth nor saw a dentist, and fluoride was almost never added to water. That’s why many elders have missing teeth. In developed nations, they usually have dentures; in poor nations, they have gaps in their mouths or very visible gold teeth—

Currently in developed nations, school-

Children’s Health Habits

Good childhood habits protect later adult health. For example, the more regular exercise children get, the less likely they are to suffer a stroke or a heart attack in adulthood (Branca et al., 2007). The health that most school-

Children’s habits during these years are strongly affected by peers and parents. When children see others routinely care for their health, social learning pushes them to do the same. Camps for children with asthma, cancer, diabetes, sickle cell anemia, and other chronic illnesses are particularly beneficial because the example of other children, and the guidance of knowledgeable adults, helps children care for themselves. Establishing good health habits is vital before adolescence, because teenage rebellion leads some children with chronic diseases to ignore special diets, pills, warning signs, and doctors unless the children themselves have incorporated such habits into daily life (Dean et al., 2010; Suris et al., 2008).

Physical Activity

Beyond the sheer fun of playing, the benefits of physical activity—

How could body movement improve brain functioning? A review of the research suggests several possible mechanisms, including direct benefits of better cerebral blood flow and increased neurotransmitters, as well as the indirect results of better mood and thus improved concentration (Singh et al., 2012). In addition, playing games with other children teaches cooperation, problem solving, and respect for teammates and opponents of many backgrounds.

Where can children reap these benefits?

Neighborhood Games

Neighborhood play is flexible. Rules and boundaries are adapted to the context (out of bounds is “past the tree” or “behind the parked truck”). Stickball, touch football, tag, hide-

Children play tag, hide and seek, or pickup basketball. They compete with one another but always according to rules, and rules that they enforce themselves without recourse to an impartial judge. The penalty for not playing by the rules is not playing, that is, social exclusion.

[Gillespie, 2010, p. 398]

For school-

An additional problem is that parents fear “stranger danger”—although one expert writes that “there is a much greater chance that your child is going to be dangerously overweight from staying inside than that he is going to be abducted” (quoted in Layden, 2004, p. 86). Indoor activities such as homework, television, and video games compete with outdoor play in every nation, perhaps especially in the United States. According to an Australian scholar:

Australian children are lucky. Here the dominant view is that children’s after school time is leisure time. In the United States, it seems that leisure time is available to fewer and fewer children. If a child performs poorly in school, recreation time rapidly becomes remediation time. For high achievers, after school time is often spent in academic enrichment.

[Vered, 2008, p. 170]

The United States is not the greatest offending nation in terms of using after-

Many parents around the world enroll their children in neighborhood organizations that offer additional opportunities for play. Culture and family affect the specifics: Some children learn golf, others tennis, others boxing. Cricket and rugby are common in England and in former British colonies such as India, Australia, and Jamaica; baseball is common in Japan, the United States, Cuba, Panama, and the Dominican Republic; soccer is central in many European, African, and Latin American nations.

Unfortunately, organized teams are less likely to include children of low SES or children with disabilities. As a result, the children most likely to benefit are least likely to participate, even when enrollment is free. The reasons are many; the consequences sad (Dearing et al., 2009).

Exercise in School

When opportunities for neighborhood play are scarce, physical education in school is a logical alternative. However, because schools are pressured to focus on test scores in academic subjects, time for physical education and recess has declined. A study of Texas elementary schools found that 24 percent had no recess at all and only 1 percent had recess several times a day (W. Zhu et al., 2010).

Texas, unfortunately, is no exception. A survey of U. S. teachers of more than 10,000 third-

Many researchers note that “many children from disadvantaged backgrounds are not free to roam their neighborhoods or even their own yards unless they are accompanied by adults. For many of these children, recess periods may be the only opportunity for them to practice their social skills with other children” (Barros et al., 2009, p. 434). Thus school exercise is least likely for children most likely to need it—

When school districts require gym, classes may be too crowded to allow active play for all the children. Ironically, schools in Japan, where many children score well on international tests, usually have several recess breaks totaling more than an hour each day. It is common for Japanese public schools to have an indoor gym and a pool.

After-

National organizations are developing guidelines to prevent concussions among 7-

Especially for Physical Education Teachers A group of parents of fourth-

Response for Physical Education Teachers: Discuss with the parents their reasons for wanting the team. Children need physical activity, but some aspects of competitive sports are better suited to adults than to children.

SUMMING UP

School-