Health Problems in Middle Childhood

Health Problems in Middle Childhood

Chronic conditions become more troubling if they interfere with school, play, and friendships. Some conditions—

Researchers increasingly recognize that every physical and psychological problem is affected by the social context and, in turn, affects that context (Jackson & Tester, 2008). Parents and children are not merely reactive: In a dynamic-

Childhood Obesity

childhood overweight In a child, having a BMI above the 85th percentile, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control’s 1980 standards for children of a given age.

childhood obesity In a child, having a BMI above the 95th percentile, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control’s 1980 standards for children of a given age.

Body mass index (BMI) is the ratio of weight to height. Childhood overweight is usually defined as a BMI above the 85th percentile, and childhood obesity is defined as a BMI above the 95th percentile of children a particular age. In 2010, 18 percent of 6-

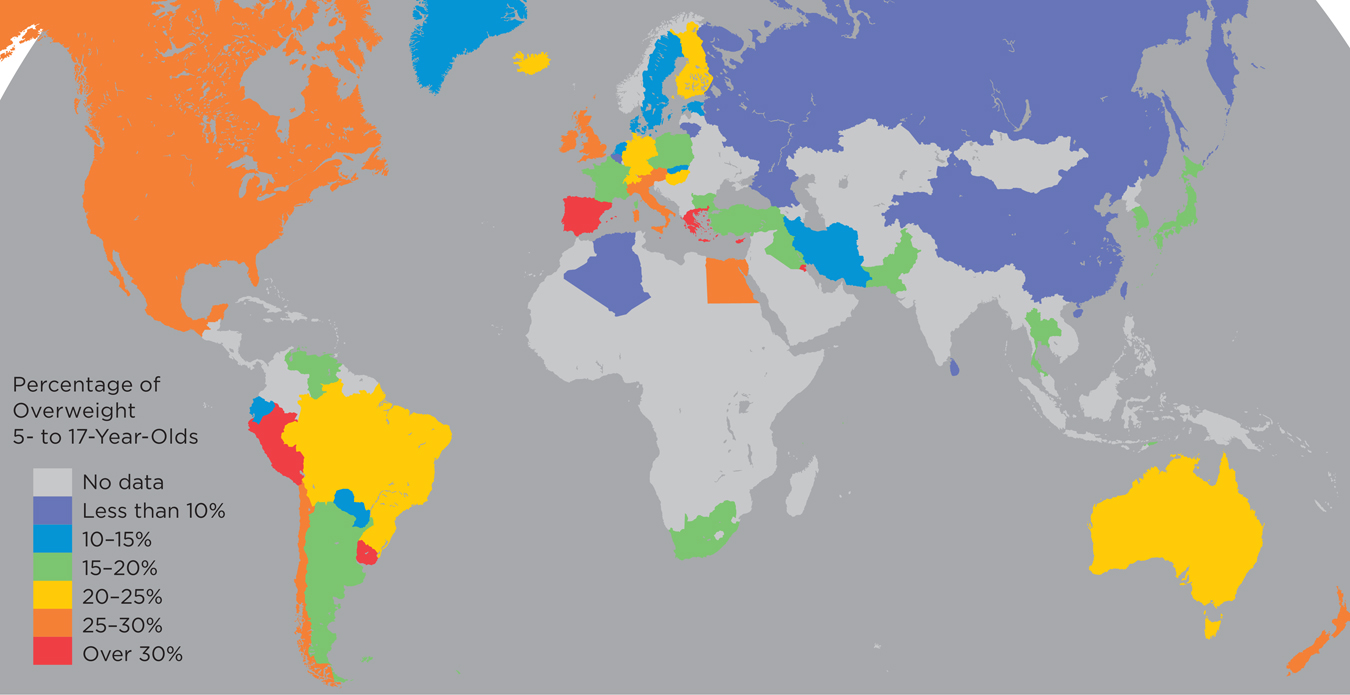

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Childhood Obesity Around the Globe

Obesity now causes more deaths worldwide than malnutrition. There are more than 42 million overweight children around the world. Obesity is caused by factors in every system—

There is hope. A multifaceted prevention effort—

SOURCE: LOBSTEIN, TIM, & DIBB (2005)

ADS AND OBESITY

Nations differ not only in obesity rates but also in children’s exposure to television ads for unhealthy food. The amount of advertising of unhealthy foods on television correlates with childhood obesity—

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION (WHO) RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PHYSICAL ACTIVITY FOR CHILDREN

SOURCES & CREDITS LISTED ON P. SC-

Especially for Teachers A child in your class is overweight, but you are hesitant to say anything to the parents, who are also overweight, because you do not want to offend them. What should you do?

Response for Teachers: Speak to the parents, not accusingly (because you know that genes and culture have a major influence on body weight) but helpfully. Alert them to the potential social and health problems their child’s weight poses. Most parents are very concerned about their child’s well-

Childhood obesity is increasing worldwide, having more than doubled since 1980 in all three nations of North America (Mexico, the United States, and Canada) (Ogden et al., 2011). Since 2000, rates seem to have leveled off in the U.S., but they have but increased in China (Ji et al., 2013). The World Health Organization uses lower cutoffs between healthy and excess weight, and thus some international statistics report even more childhood obesity (Shields & Tremblay, 2010) (see Visualizing Development, p. 314).

Although rates have stabilized in the United States, the current plateau is far too high. About one-

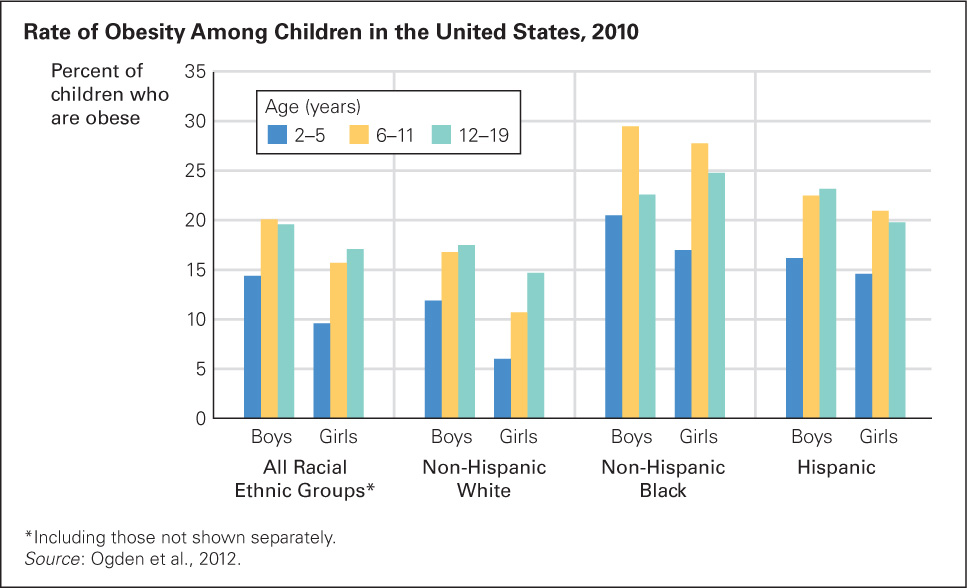

Observation Quiz Generally, rates of obesity increase every year from ages 2 to 19, but boys and girls in one group here seem less likely to be overweight in adolescence than in middle childhood. Which group, and why?

Answer to Observation Quiz: Non-

FIGURE 11.2

Fatter and Fatter As you see, the incidence of obesity (defined here as a BMI above the 95th percentile, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts) increases as children grow older. Not shown is the rate in infancy, which is significantly lower for every group. The “All Groups” rate includes children of groups not shown separately, such as biracial, Asian, Hawaiian, Alaskan native, and American Indian.Childhood overweight correlates with asthma, high blood pressure, and elevated cholesterol (especially LDL, the “lousy” cholesterol). As excessive weight builds, school achievement often decreases, self-

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

What Contributes to Childhood Obesity?

There are “hundreds if not thousands of contributing factors” for childhood obesity, from the cells of the body to the norms of the society (Harrison et al., 2011, p. 51). One way to think of it is to consider the many opportunities and practices that might mitigate obesity in six domains that begin with the letter C—

More than 200 genes affect weight by influencing activity level, hunger, food preferences, body type, and metabolism (Gluckman & Hanson, 2006). Having two copies of an allele called FTO (inherited by 16 percent of all European Americans) increases the likelihood of both obesity and diabetes (Frayling et al., 2007). New genes and alleles that affect obesity, never acting alone, are discovered virtually every month (Dunmore, 2013).

Knowing that genes are involved may slow down the impulse to blame fat people for their weight, but problems at the cellular level are epigenetic, and they represent only one of the six categories of causes mentioned above. Further, genes cannot be the reason for increases in obesity, since genes change little from one generation to the next (Harrison et al., 2011).

Family practices, however, can change, and they have in the past decades. Obesity is more common in infants who are not breast-

During middle childhood, children themselves contribute to their weight gain. They have pester power—the ability to get adults to do what they want (Powell et al., 2011). Often they pester their parents to give them calorie-

On average, family contexts changed for the worse toward the end of the twentieth century in North America and are now spreading worldwide. For instance, pester power increases as family size decreases. That makes childhood obesity collateral damage from improvements in contraception.

Attempts to restrict foods that are high in sugar and fat clash with the sales efforts corporations that sell snacks for a profit. Some success, however, has occurred in policies within schools that increasingly serve healthy foods and monitor the location and contents of vending machines.

Communities and countries can affect the prevalence of parks, bike paths, and sidewalks and decrease subsidies for corn oil and sugar. Simply offering healthy food is not enough to convince children to change their diet; context and culture are crucial (Hanks et al., 2013).

Cultural sensitivity is crucial, since each ethnic group has preferred foods and family patterns. To work against culture is foolish, but working within cultures can protect the children.

For example, African Americans may consider fried fish part of their culture, but so are baked fish and a variety of greens; Mexican Americans may relish rice and beans, but those can be cooked without added fat. Immigrants who want to “eat American” may need to learn that fast-

Rather than trying to zero in on any single factor, a dynamic-

BLOOMIMAGE/GETTY IMAGES

Asthma

asthma A chronic disease of the respiratory system in which inflammation narrows the airways from the nose and mouth to the lungs, causing difficulty in breathing. Signs and symptoms include wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and coughing.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways that makes breathing difficult. Sufferers have periodic attacks, sometimes requiring a rush to the hospital emergency room, a frightening experience for children. Although people of every age experience asthma, rates are highest among school-

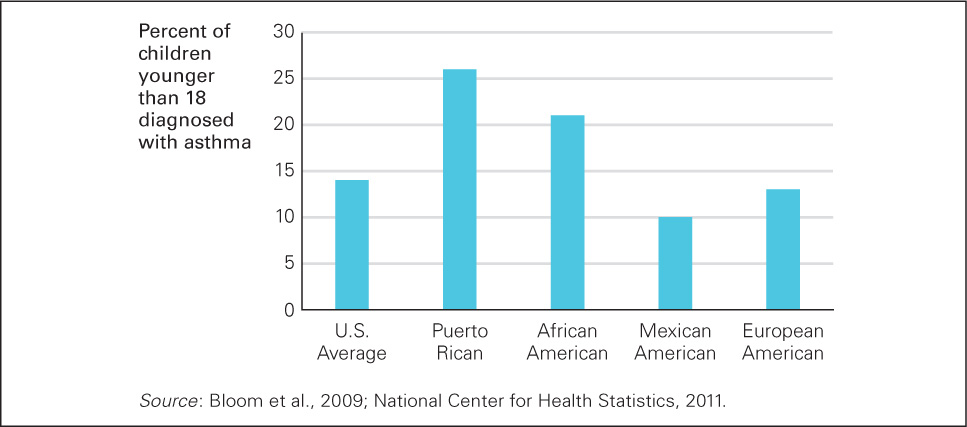

In the United States, child asthma rates have tripled since 1980. (See Figure 11.3 for current rates for those younger than 18 years old.) Parents report that 10.2 percent of U.S. 5-

FIGURE 11.3

Not Breathing Easy Of all U.S. children younger than 18, 14 percent have been diagnosed at least once with asthma. Why are Puerto Rican and African American children more likely to have asthma? Does the answer have to do with nature or nurture, genetics or pollution?

Researchers have long sought to find the causes of asthma. A few alleles have been identified as contributing factors, but none acts in isolation (Akinbami et al., 2010; Bossé & Hudson, 2007). Some make asthma difficult to control, while others cause milder, more controllable asthma (Almomani et al., 2013). Several aspects of modern life—

Some experts suggest a hygiene hypothesis: that “the immune system needs to tangle with microbes when we are young” (Leslie, 2012, p. 1428), that children are overprotected from viruses and bacteria. In their concern about hygiene, parents keep young children from exposure to minor infections and diseases that would strengthen their immunity. This hypothesis is supported by data showing that (1) first-

Especially for Parents Suppose that you always serve dinner with the television on, tuned to a news broadcast. Your hope is that your children will learn about the world as they eat. Can this practice be harmful?

Response for Parents: Habitual TV watching correlates with obesity, so you may be damaging your children’s health rather than improving their intellect. Your children would probably profit more if you were to make dinner a time for family conversation about world events.

None of these factors, however, proves the hygiene hypothesis. Perhaps farm children are protected by drinking unpasteurized milk, by outdoor chores, or by genes that are more common in farm families, rather than by being more often exposed to a range of bacteria (von Mutius & Vercelli, 2010).

The incidence of asthma increases as nations get richer, dramatically evident since 2000 in Brazil and China. Better hygiene for wealthier children is one explanation, but so is increasing urbanization, which correlates with more cars, more pollution, more allergens, and better medical diagnoses (Cruz et al., 2010). One review of the hygiene hypothesis notes that “the picture can be dishearteningly complex” (Couzin-

Since developmentalists realize that every day of school absence—

Consider a study of 133 Latino adult smokers, all caregivers of children with asthma. They were not necessarily willing to quit cigarettes, but they agreed to allow a Spanish-

Three months later, one-

Other research confirms that most parents want to provide good care (many wonder how) and that many adults, including those who are neither parents nor Latino, want to protect children but do not know how. Air pollution, for instance, is considered a general environmental problem, but many adults do not realize the impact it has on children.

SUMMING UP

Some children have chronic health problems that interfere with school and friendship. Among these are obesity and asthma, both of which are increasing in every nation and have genetic and environmental causes. Childhood obesity may seem harmless, but it leads to social problems among classmates and severe health problems later on. Asthma’s harm is more immediate: Asthmatic children often miss school and are rushed to emergency rooms, gasping for air. Although genes predispose some children to each particular health problem, family practices and neighborhood context can increase rates of obesity and asthma, and many society-