The Nature of the Child

The Nature of the Child

As explained in the previous two chapters, steady growth, brain maturation, and intellectual advances make middle childhood a time for more independence (see At About This Time). Children acquire an “increasing ability to regulate themselves, to take responsibility, and to exercise self-

One practical result is that between ages 6 and 11, children learn to care for themselves. They not only hold their own spoon but also make their own dinner, not only zip their own pants but also pack their own suitcases, not only walk to school but also organize games with friends. They venture outdoors alone. Boys are especially likely to engage in activities without their parents’ awareness or approval (Munroe & Romney, 2006). This budding independence fosters growth.

Industry and Inferiority

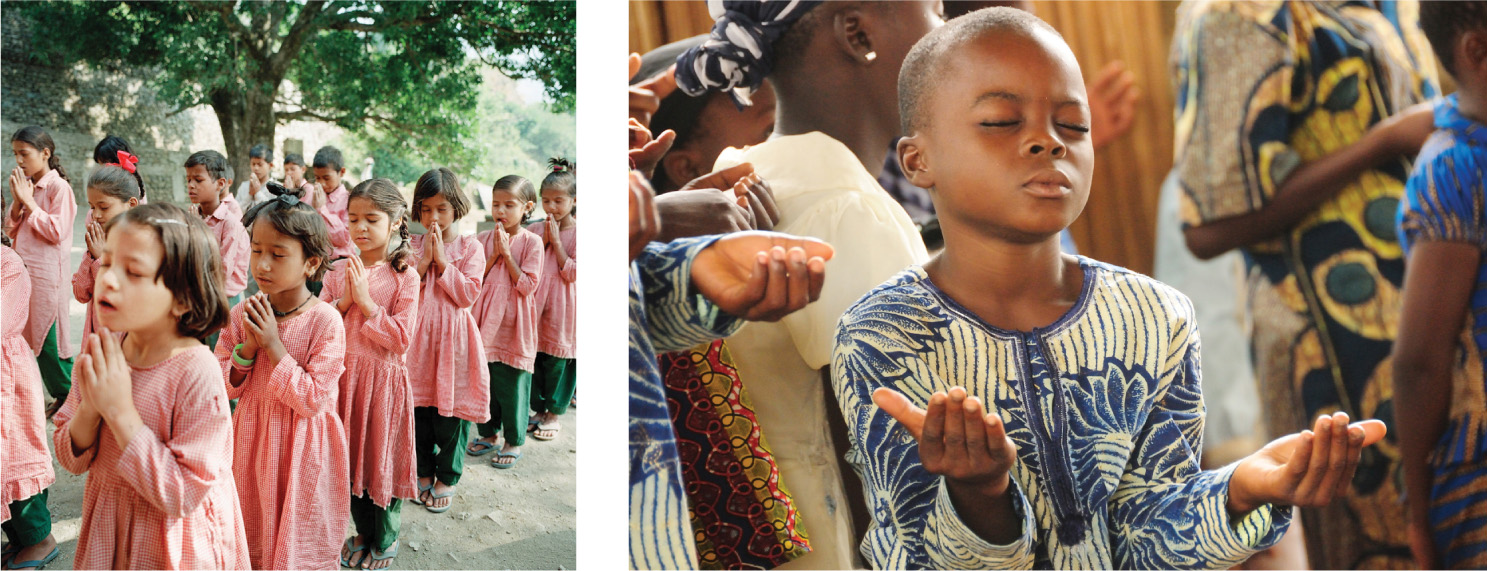

Throughout the centuries and in every culture, school-

Erikson’s Insights

industry versus inferiority The fourth of Erikson’s eight psychosocial crises, during which children attempt to master many skills, developing a sense of themselves as either industrious or inferior, competent or incompetent.

With regard to his fourth psychosocial crisis, industry versus inferiority, Erikson noted that the child “must forget past hopes and wishes, while his exuberant imagination is tamed and harnessed to the laws of impersonal things,” becoming “ready to apply himself to given skills and tasks” (Erikson, 1963, pp. 258, 259).

| Signs of Psychosocial Maturation over the Years of Middle Childhood* | ||

|---|---|---|

| Children responsibly perform specific chores. | ||

| Children make decisions about a weekly allowance. | ||

| Children can tell time, and they have set times for various activities. | ||

| Children have homework, including some assignments over several days. | ||

| Children are less often punished than when they were younger. | ||

| Children try to conform to peers in clothes, language, and so on. | ||

| Children voice preferences about their after- |

||

| Children are responsible for younger children, pets, and, in some places, work. | ||

| Children strive for independence from parents. | ||

| *Of course, culture is crucial. For example, giving a child an allowance is typical for middle class children in developed nations since about 1960. It was rare, or completely absent, in earlier times and other places. | ||

Think of learning to read and add, both of which are painstaking and boring tasks. For instance, slowly sounding out “Jane has a dog” or writing “3 + 4 = 7” for the hundredth time is not exciting. Yet school-

Overall, children judge themselves as either industrious or inferior—deciding whether they are competent or incompetent, productive or useless, winners or losers. Self-

Freud on Latency

latency Freud’s term for middle childhood, during which children’s emotional drives and psychosexual needs are quiet (latent). Freud thought that sexual conflicts from earlier stages are only temporarily submerged, bursting forth again at puberty.

Sigmund Freud described this period as latency, a time when emotional drives are quiet (latent) and unconscious sexual conflicts are submerged. Some experts complain that “middle childhood has been neglected at least since Freud relegated these years to the status of an uninteresting ‘latency period’” (Huston & Ripke, 2006, p. 7).

But in one sense, at least, Freud was correct: Sexual impulses are absent, or at least hidden. Even when children were betrothed before age 12 (rare today but common in earlier eras), the young husband and wife had little interaction. Everywhere, boys and girls typically choose to be with others of their own sex. Indeed, boys who write “Girls stay out!” and girls who complain that “boys stink” are typical.

Self-Concept

As children mature, they develop their self-

social comparison The tendency to assess one’s abilities, achievements, social status, and other attributes by measuring them against other people, especially one’s peers.

Crucial during middle childhood is social comparison—comparing one’s self to others (Davis-

This means that some children—

For all children, this increasing self-

In addition, because children think concretely during middle childhood, materialism increases, and attributes that adults might find superficial (hair texture, sock patterns) become important, making self-

Culture and Self-Esteem

Academic and social competence are aided by realistic self-

The same consequences occur if self-

TAO IMAGES LIMITED/GETTY IMAGES

High self-

Often in the United States, children’s successes are praised and teachers are wary of being critical, especially in middle childhood. For example, some schools issue report cards with grades ranging from “Excellent” to “Needs improvement” instead of from A to F. An opposite trend is found in the national reforms of education, explained in Chapter 12. Because of the No Child Left Behind Act, some schools are rated as failing. Obviously culture, cohort, and age all influence attitudes toward high self-

One crucial component of self-

For example, children who fail a test are devastated if failure means they are not smart. However, process-

Resilience and Stress

In infancy and early childhood, children depend on their immediate families for food, learning, and life itself. Then “experiences in middle childhood can sustain, magnify, or reverse the advantages or disadvantages that children acquire in the preschool years” (Huston & Ripke, 2006, p. 2). Some children continue to benefit from supportive families, and others escape destructive family influences by finding their own niche in the larger world.

Surprisingly, some children seem unscathed by early experiences. They have been called “resilient” or even “invincible.” Current thinking about resilience (see Table 13.1), with insights from dynamic-

| 1965 | All children have the same needs for healthy development. |

| 1970 | Some conditions or circumstances— |

| 1975 | All children are not the same. Some children are resilient, coping easily with stressors that cause harm in other children. |

| 1980 | Nothing inevitably causes harm. All the factors thought to be risks in 1970 (e.g., day care) are sometimes beneficial. |

| 1985 | Factors beyond the family, both in the child (low birthweight, prenatal alcohol exposure, aggressive temperament) and in the community (poverty, violence), can harm children. |

| 1990 | Risk– |

| 1995 | No child is invincibly resilient. Risks are always harmful— |

| 2000 | Risk– |

| 2005 | Focus on strengths, not risks. Assets in child (intelligence, personality), family (secure attachment, warmth), community (schools, after- |

| 2010 | Strengths vary by culture and national values. Both universal needs and local variations must be recognized and respected. |

| 2012 | Genes, family structures, and cultural practices can be either strengths or weaknesses. Differential sensitivity means identical stressors can benefit one child and harm another. |

Differential sensitivity is apparent, not only because of genes but also because of early child rearing, preschool education, and sociocultural values. Some children are hardy, more like dandelions than orchids, but all are influenced by their situation (Ellis & Boyce, 2008).

resilience The capacity to adapt well to significant adversity and to overcome serious stress.

Resilience has been defined as “a dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity” (Luthar et al., 2000, p. 543). Note the three parts of this definition:

- Resilience is dynamic, not a stable trait. That means a given person may be resilient at some periods but not others.

- Resilience is a positive adaptation to stress. For example, if parental rejection leads a child to a closer relationship with another adult, that is positive adaptation, not mere passive endurance. That child is resilient.

- Adversity must be significant. Some adversities are comparatively minor (large class size, poor vision), and some are major (victimization, neglect). Children need to cope with both kinds, but not all coping qualifies them as resilient.

Cumulative Stress

One important discovery is that accumulated stresses over time, including minor ones (called “daily hassles”), are more devastating than an isolated major stress. Almost every child can withstand one trauma, but repeated stresses make resilience difficult (Jaffee et al., 2007).

One international example comes from Sri Lanka, where many children in the first decade of the twenty-

The social context, especially supportive adults who do not blame the child, is crucial. A chilling example comes from the “child soldiers” in the 1991–

These war-

Cognitive Coping

Obviously, this example from Sierra Leone is extreme, but the general finding appears in other research as well. Disasters take a toll, but resilience is possible. Factors in the child (especially problem-

One pivotal factor is the child’s own interpretation of events. Cortisol (the stress hormone) increases in low-

In general, a child’s interpretation of a family situation (poverty, divorce, and so on) determines how it affects him or her (Olson & Dweck, 2008). Some children consider the family they were born into a temporary hardship; they look forward to the day when they can leave childhood behind. The opposite reaction is called parentification, when children feel responsible for the entire family, acting as parents who take care of everyone, including their actual parents (Byng-

In another example, children who endured hurricane Katrina were affected by their thoughts, positive and negative, more than by factors one might expect, such as their caregivers’ distress (Kilmer & Gil-

NAFTALI HILGER/LAIF/REDUX

SUMMING UP

Children gain in maturity and responsibility during the school years. According to Erikson, the crisis of industry versus inferiority generates feelings of confidence or self-

Often children develop more realistic self-