Families and Children

Families and Children

No one doubts that genes affect personality as well as ability, that peers are vital, and that schools and cultures influence what, and how much, children learn. Some go farther, suggesting that genes, peers, and communities have so much influence that parenting has little impact—

Shared and Nonshared Environments

Many studies have found that children are much less affected by shared environment (influences that arise from being in the same environment, such as for two siblings living in one home, raised by their parents) than by nonshared environment (e.g., the different experiences of two siblings).

Most personality traits and intellectual characteristics can be traced to genes and nonshared environments, with little left over for the shared influence of being raised by the same parents. Even psychopathology, happiness, and sexual orientation (Burt, 2009; Långström et al., 2010; Bartels et al., 2013) arise primarily from genes and nonshared environment.

Especially for Scientists How would you determine whether or not parents treat all their children the same?

Response for Scientists: Proof is very difficult when human interaction is the subject of investigation, since random assignment is impossible. Ideally, researchers would find identical twins being raised together and would then observe the parents’ behavior over the years.

Since many research studies find that shared environment has little impact, could it be that parents are merely caretakers, necessary for providing basic care (food, shelter) but inconsequential no matter what rules, routines, or responses they provide? If a child becomes a murderer or a hero, don’t blame or credit the parents!

Recent findings, however, reassert parent power. The analysis of shared and nonshared influences was correct, but the conclusion was based on a false assumption. Siblings raised together do not share the same environment.

For example, if relocation, divorce, unemployment, or a new job occurs in a family, the impact depends on each child’s age, genes, resilience, and gender. Moving to another town upsets a school-

The age and gender variations above do not apply for all siblings: Differential sensitivity means that one child is more affected, for better or worse, than another (Pluess & Belsky, 2010). When siblings are raised together, the mix of genes, age, and gender may lead one child to become antisocial, another to have a personality disorder, and a third to be resilient, capable, and strong (Beauchaine et al., 2009). This applies even to monozygotic twins, as the following explains.

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

“I Always Dressed One in Blue Stuff…”

An expert team of scientists compared 1,000 sets of monozygotic twins reared by their biological parents (Caspi et al., 2004). Obviously, the pairs were identical in genes, sex, and age. The researchers asked the mothers to describe each twin. Descriptions ranged from very positive (“my ray of sunshine”) to very negative (“I wish I never had her…. She’s a cow, I hate her”) (quoted in Caspi et al., 2004, p. 153). Many mothers noted personality differences between their twins. For example, one mother said:

Susan can be very sweet. She loves babies…she can be insecure…she flutters and dances around…. There’s not much between her ears…. She’s exceptionally vain, more so than Ann. Ann loves any game involving a ball, very sporty, climbs trees, very much a tomboy. One is a serious tomboy and one’s a serious girlie girl. Even when they were babies I always dressed one in blue stuff and one in pink stuff.

[quoted in Caspi et al., 2004, p. 156]

Some mothers rejected one twin but not the other:

He was in the hospital and everyone was all “poor Jeff, poor Jeff” and I started thinking, “Well, what about me? I’m the one’s just had twins. I’m the one’s going through this, he’s a seven-

[quoted in Caspi et al., 2004, p. 156]

This mother blamed Jeff for favoring his father: “Jeff would do anything for Don but he wouldn’t for me, and no matter what I did for either of them [Don or Jeff] it wouldn’t be right” (p. 157). She said Mike was much more lovable.

The researchers measured personality at age 5 (assessing, among other things, antisocial behavior as reported by kindergarten teachers) and then measured each twin’s personality two years later. They found that if the mothers were more negative toward one of their twins, that twin became more antisocial, more likely to fight, steal, and hurt others at age 7 than at age 5, unlike the favored twin.

These researchers acknowledge that many other nonshared factors—

Family Function and Family Structure

family structure The legal and genetic relationships among relatives living in the same home; includes nuclear family, extended family, stepfamily, and so on.

family function The way a family works to meet the needs of its members. Children need families to provide basic material necessities, to encourage learning, to help them develop self-

Family structure refers to the legal and genetic connections among related people living in the same household. Families are single-

Function is more important than structure; everyone always needs family love and encouragement, which can come from parents, grandparents, siblings, or any other family member. Beyond that, people’s needs differ depending on how old they are: Infants need responsive caregiving, teenagers need guidance, young adults need freedom, the aged need respect.

The Needs of Children in Middle Childhood

What do school-

- Physical necessities. Although 6-

to 11- year- olds eat, dress, and go to sleep without help, families provide food, clothing, and shelter. - Learning. These are prime learning years: Families support, encourage, and guide education.

- Self-

respect . Because children at about age 6 become much more self-critical and socially aware, families provide opportunities for success (in sports, the arts, or other arenas if academic success is difficult). - Peer relationships. Families choose schools and neighborhoods with friendly children, and then arrange play dates, group activities, overnights, and so on.

- Harmony and stability. Families provide protective, predictable routines with a home that is a safe, peaceful haven.

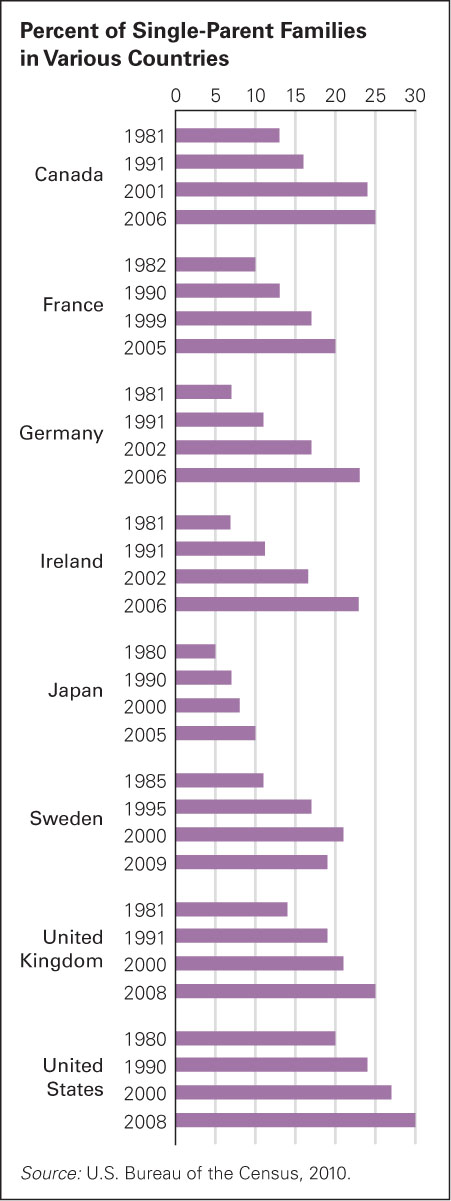

FIGURE 13.1

Single Parents Of all the households with children, a rising percentage of them are headed by a single parent. In some countries, many households are headed by two unmarried parents, a structure not shown here.The final item on the list above is especially crucial in middle childhood: Children cherish safety and stability, not change (Turner et al., 2013). Ironically, many parents move from one neighborhood or school to another during these years. Children who move frequently are significantly harmed, academically and psychologically, but resilience is possible (Cutuli et al., 2013).

The problems arising from instability are evident for U.S. children in military families. Enlisted parents tend to have higher incomes, better health care, and more education than do civilians from the same backgrounds. But they have one major disadvantage. Military children (dubbed “military brats”) have more emotional problems and lower school achievement than do their peers from civilian families for the following reason:

Military parents are continually leaving, returning, leaving again. School work suffers, more for boys than for girls, and…reports of depression and behavioral problems go up when a parent is deployed.

[Hall, 2008, p. 52]

The U.S. military has instituted a special program to help children whose parents are deployed. Caregivers of such children are encouraged to avoid changes in the child’s life: no new homes, new rules, or new schools (Lester et al., 2011).

Diverse Structures

Worldwide today there are more single-

Almost two-

Two-

|

Single-

|

| *Less than 1 percent of U.S. children live without any caregiving adult; they are not included in this table.Source: The percentages in this table are estimates, based on data in U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract and Current Population Reports, America’s Families and Living Arrangements, and Pew Research Center reports. The category “extended family” in this table is higher than in most published statistics, since some families do not tell official authorities about relatives living with them. |

nuclear family A family that consists of a father, a mother, and their biological children under age 18.

single-

Rates of single-

extended family A family of three or more generations living in one household.

The distinction between one-

polygamous family A family consisting of one man, several wives, and their children.

In many nations, the polygamous family (one husband with two or more wives) is an acceptable family structure. Generally in polygamous families, income per child is reduced, and education, especially for the girls, is limited (Omariba & Boyle, 2007). Polygamy is rare—

Connecting Family Structure and Function

More important for the children is not the structure of their family but how that family functions. The two are related; structure influences (but does not determine) function. The crucial question is whether the structure makes it more or less likely that the five family functions mentioned earlier (physical necessities, learning, self-

GREG ELMS/GETTY IMAGES

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

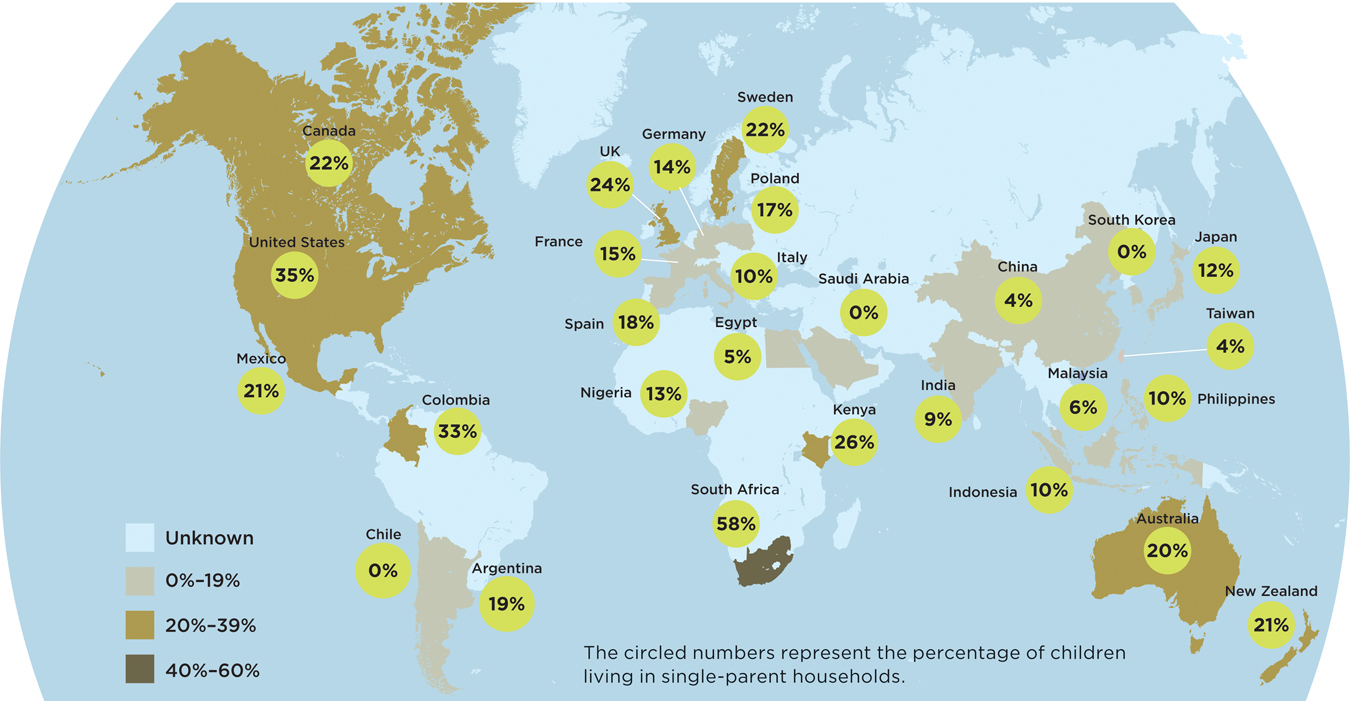

A Wedding, or Not? Family Structures Around the World

Children fare best when both parents actively care for them every day. This is most likely to occur if the parents are married, although there are many exceptions. Many developmentalists now focus on the rate of single parenthood, shown on this map. Some single parents raise children well, but the risk of neglect, poverty, and instability in single-

RATES OF SINGLE PARENTHOOD

A young couple in love and committed to each other—

Cohabitation and marriage rates change from year to year and from culture to culture. These two examples are illustrative and approximate. Family-

Two-Parent Families

On average, nuclear families function best; children in the nuclear structure tend to achieve better in school with fewer psychological problems. A scholar who summarized dozens of studies concludes: “Children living with two biological married parents experience better educational, social, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes than do other children” (Brown, 2010, p. 1062). Why? Does this mean that parents should all marry and stay married? Not necessarily: Some benefits are correlates, not causes.

Education, earning potential, and emotional maturity all make it more likely that people will marry, have children, stay married, and establish a nuclear family. Thus, brides and grooms tend to have personal assets before they marry, and those assets are brought to their new family. That means that the correlation between child success and married parents occurs partly because of who marries, not because of the wedding.

Income also correlates with family structure. Usually, if everyone can afford it, relatives live independently, apart from the married couple. That means that, at least in the United States, an extended family suggests that someone is financially dependent.

These two factors explain some of the correlation, but not all of it. After marriage, ideally, mutual affection encourages both partners to become wealthier and healthier than either would be alone. This often occurs—

Shared parenting decreases the risk of child maltreatment and makes it more likely that children will have someone to read to them, check their homework, invite their friends over, buy them new clothes, and save for their education. Of course, having two married parents does not guarantee an alliance. One of my students wrote:

My mother externalized her feelings with outbursts of rage, lashing out and breaking things, while my father internalized his feelings by withdrawing, being silent and looking the other way. One could say I was being raised by bipolar parents. Growing up, I would describe my mom as the Tasmanian devil and my father as the ostrich, with his head in the sand…. My mother disciplined with corporal punishment as well as with psychological control, while my father was permissive. What a pair.

[C., 2013]

This student is now a single parent, having twice married, given birth, and divorced. She is one example of a general finding. The effects of a childhood family can echo in adulthood. For college students, this effect may be financial as well as psychological. A survey of college tuition payments found that nuclear families provided the most money for college.

This was not simply because two-

Adoptive and same-

Considerable research has focused on stepparent families. The primary advantage of this family structure is financial, especially when compared with most single-

Stability is threatened not only by the inevitable instability of having a new parent. Compared with other two-

Harmony is difficult to achieve (Martin-

Children who are given a stepparent may be angry or sad; they often create problems, and hence disagreements, for their remarried parents. Further, disputes between half-

Finally, when grandparents provide full-

Skipped-

Single-Parent Families

Especially for Single Parents You have heard that children raised in one-

Response for Single Parents: Do not get married mainly to provide a second parent for your child. If you were to do so, things would probably get worse rather than better. Do make an effort to have friends of both sexes with whom your child can interact.

On average, the single-

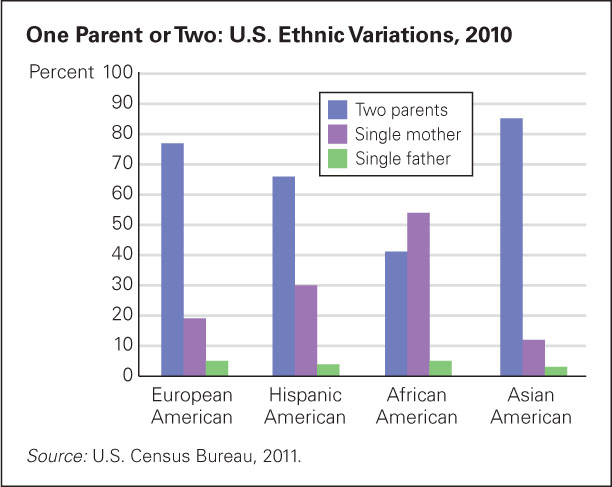

One correlate of support is whether or not the community, ethnic group, or nation helps single parents. More than half of African American 6-

FIGURE 13.2

Diverse Families The fact that family structure is affected partly by ethnicity has implications for everyone in the family. It is easier to be a single parent if there are others of the same background who are also single parents.In some European nations, single parents are given many public resources; in other nations, they are shamed as well as unsupported. Children benefit or suffer accordingly.

A CASE TO STUDY

How Hard Is It to Be a Kid?

Neesha’s fourth-

The counselor spoke to Neesha’s mother, Tanya, a single parent who was depressed and worried about paying the rent on a tiny apartment where she had moved when Neesha’s father left three years earlier. He lived with his girlfriend, now with a baby. Tanya said she had no problems with Neesha, who was “more like a little mother than a kid,” unlike her 15-

Tyrone was recently beaten up badly as part of a gang initiation, a group he considered “like a family.” He was currently in juvenile detention, after being arrested for stealing bicycle parts. Note the nonshared environment here: Although the siblings grew up together and their father left them both, 12-

The school counselor also spoke with Neesha.

Neesha volunteered that she worried a lot about things and that sometimes when she worries she has a hard time falling asleep…. she got in trouble for being late so many times, but it was hard to wake up. Her mom was sleeping late because she was working more nights cleaning offices…. Neesha said she got so far behind that she just gave up. She was also having problems with the other girls in the class, who were starting to tease her about sleeping in class and not doing her work. She said they called her names like “Sleepy” and “Dummy.” She said that at first it made her very sad, and then it made her very mad. That’s when she started to hit them to make them stop.

[Wilmhurst, 2011, pp. 152–

Neesha is coping with poverty, a depressed mother, an absent father, a delinquent brother, and classmate bullying. She showed resilience—

The school principal received a call from Neesha’s mother, who asked that her daughter not be sent home from school because she was going to kill herself. She was holding a loaded gun in her hand and she had to do it, because she was not going to make this month’s rent. She could not take it any longer, but she did not want Neesha to come home and find her dead…. While the guidance counselor continued to keep the mother talking, the school contacted the police, who apprehended [the] mom while she was talking on her cell phone…. The loaded gun was on her lap…. The mother was taken to the local psychiatric facility.

[Wilmhurst, 2011, pp. 154–

Whether Neesha’s resilience will continue depends on her ability to find support beyond her family. Perhaps the school counselor will help:

When asked if she would like to meet with the school psychologist once in a while, just to talk about her worries, Neesha said she would like that very much. After she left the office, she turned and thanked the psychologist for working with her, and added, “You know, sometimes it’s hard being a kid.”

[Wilmhurst, 2011, p. 154]

All these are generalities: Contrary to the averages, thousands of nuclear families are destructive, thousands of stepparents provide excellent care, and thousands of single-

Family Trouble

Two factors interfere with family function in every structure, ethnic group, and nation: low income and high conflict. Many families experience both because financial stress increases conflict and vice versa (McLanahan, 2009).

A VIEW FROM SCIENCE

Divorce

Scientists try to provide analysis and insight, based on empirical data (of course), but the task goes far beyond reporting facts. Regarding divorce, thousands of studies and several opposing opinions need to be considered, analyzed, and combined—

Among the facts that need analysis are these:

- The United States leads the world in the rates of marriage, divorce, and remarriage, with almost half of all marriages ending in divorce. Why?

- Single parents, cohabiting parents, and stepparents sometimes provide good care, but children tend to do best in nuclear families with married parents. Why?

- Divorce often impairs children’s academic achievement and psychosocial development for years, even decades. Why?

The problem, Cherlin (2009) contends, is that U.S. culture is conflicted: Marriage is idolized, but so is personal freedom. As a result, many people assert their independence by marrying without consulting their parents or community. Then, when child care becomes overwhelming and family or public support is lacking, the marriage becomes strained, so they divorce. Because marriage remains the ideal, they blame their former mate or their own poor decision, not the institution.

Consequently, they seek another marriage, which may lead to another divorce. (Divorced people are more likely to remarry than single people their age are to marry, but second marriages fail more often than first marriages.) All this is in accord with personal freedom, but repeated transitions harm children.

This leads to a related insight. Cherlin suggests that the main reason children are harmed by divorce—

Scholars now describe divorce as a process, with transitions and conflicts before and after the formal event (Magnuson & Berger, 2009; Potter, 2010). As you remember, resilience is difficult when the child must contend with repeated changes and ongoing hassles—

Beyond analysis and insight, the other task of developmental science is to provide practical suggestions. Most scholars would agree with the following:

- Marriage commitments need to be made slowly and carefully, to minimize the risk of divorce. It takes time to develop intimacy and commitment.

- Once married, couples need to work to keep the relationship strong. Often happiness dips after the birth of the first child. Knowing that, new parents need to do together what they love—

dancing, traveling, praying, whatever. - Divorcing parents need to minimize transitions and maintain a child’s relationships with both parents. Often a mediator—

who advocates for the child, not for either parent— can help. (Mediators are required in some U.S. jurisdictions.) - In middle childhood, schools can provide vital support. Routines, friendships, and academic success may be especially crucial when a child’s family is chaotic.

This may sound idealistic. However, another scientist, who has also studied divorced families for decades, writes:

Although divorce leads to an increase in stressful life events, such as poverty, psychological and health problems in parents, and inept parenting, it also may be associated with escape from conflict, the building of new more harmonious fulfilling relationships, and the opportunity for personal growth and individuation.

[Hetherington, 2006, p. 204]

Not every parent should marry, not every marriage should continue, and not every child is devastated by divorce. However, every child benefits from all five family functions. Adults can provide that. Scientists hope they do.

Wealth and Poverty

Family income correlates with both function and structure. Marriage rates fall in times of recession, and divorce correlates with unemployment. The effects of poverty are cumulative; low socioeconomic status (SES) may be especially damaging for children if it begins in infancy and continues in middle childhood (Duncan et al., 2010).

Several scholars have developed the family-

Reaction to wealth may also cause problems. Children in high-

Remember the dynamic-

Adults whose upbringing included less education and impaired emotional control are more likely to have difficulty finding employment and raising their children, and then low income adds to their difficulties (Schofield et al., 2011). Health problems in infancy may lead to “biologically embedded” stresses that impair adult well-

If all this is so, more income means better family functioning. For example, children in single-

Conflict

There is no controversy about conflict: Every researcher agrees that family conflict harms children, especially when adults fight about child rearing. Such fights are more common in stepfamilies, divorced families, and extended families, but nuclear families are not immune. In every family, children suffer not only if they are abused, physically or emotionally, but also if they are merely witness to their parents’ fighting. Fights between siblings can be harmful, too (Turner et al., 2013).

Researchers wonder whether one reason that children are emotionally troubled in families with feuding parents is inherited tendencies, instead of directly caused by seeing the parents fight. The idea is that the parents’ genes lead to marital problems, and that those same genes lead to children’s difficulties. If that is the case, then it doesn’t matter if children are aware of their parents’ conflicts.

This idea was tested in a longitudinal study of 867 twin pairs (388 monozygotic pairs and 479 dizygotic pairs), all married with an adolescent child. Each adolescent was compared to his or her cousin, the child of one parent’s twin (Schermerhorn et al., 2011). Thus, this study had data on family conflict from 5,202 individuals—

The researchers found that, although genes had some effect, witnessing conflict itself had a powerful effect on the children, causing externalizing problems in the boys and internalizing problems in the girls. In this study, quiet disagreements did not much harm the child, but open conflict (such as yelling when children could hear) or divorce did (Schermerhorn et al., 2011). That leads to an obvious conclusion: Parents should not fight in front of the children.

SUMMING UP

Families serve five crucial functions for school-

The nuclear, two-