Growth and Nutrition

Growth and Nutrition

Puberty entails transformation of every part of the body, each change affecting the others. Here we discuss biological growth, the nutrition that fuels that growth, and the eating disorders that disrupt it. Next we will focus on the two other aspects of pubertal transformation, brain reorganization and sexual maturation.

Growing Bigger and Stronger

growth spurt The relatively sudden and rapid physical growth that occurs during puberty. Each body part increases in size on a schedule: Weight usually precedes height, and growth of the limbs precedes growth of the torso.

The first set of changes is called the growth spurt—a sudden, uneven jump in the size of almost every body part, turning children into adults. Growth proceeds from the extremities to the core (the opposite of the earlier proximodistal growth). Thus, fingers and toes lengthen before hands and feet, hands and feet before arms and legs, arms and legs before the torso. This growth is not always symmetrical: One foot, one breast, or even one ear may grow later than the other.

Because the torso is the last body part to grow, many pubescent children are temporarily big-

Sequence: Weight, Height, Muscles

FIGURE 14.4

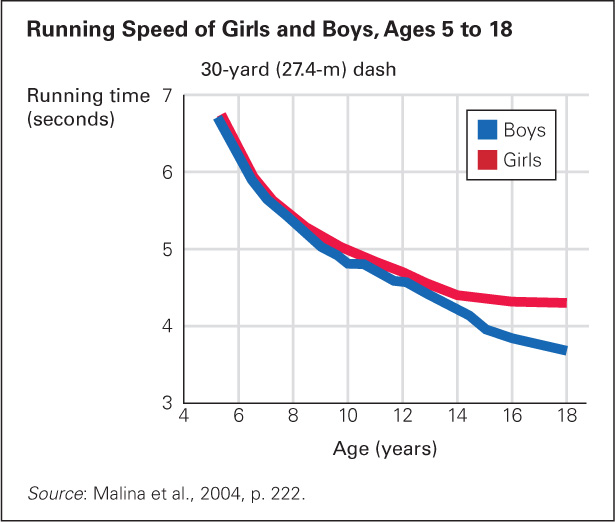

Little Difference Both sexes develop longer and stronger legs during puberty.As the growth spurt begins, children eat more and gain weight. Exactly when, where, and how much weight they gain depends on heredity, hormones, diet, exercise, and gender. By age 17, the average girl has twice the percentage of body fat as her male classmate, whose increased weight is mostly muscle (Roche & Sun, 2003).

A height spurt follows the weight spurt; then a year or two later a muscle spurt occurs. Thus, the pudginess and clumsiness of early puberty are usually gone by late adolescence. Arm muscles develop particularly in boys, doubling in strength from age 8 to 18. Other muscles are gender-

Organ Growth

In both sexes organs mature in much the same way. Lungs triple in weight; consequently, adolescents breathe more deeply and slowly. The heart doubles in size as the heartbeat slows, decreasing the pulse rate while increasing blood pressure (Malina et al., 2004). Consequently, endurance improves: Some teenagers can run for miles or dance for hours. Red blood cells increase in both sexes, but dramatically more so in boys, which aids oxygen transport during intense exercise.

Both weight and height increase before muscles and internal organs: Athletic training and weight lifting should be tailored to an adolescent’s size the previous year, to protect immature muscles and organs. Sports injuries are the most common school accidents, and they increase at puberty. One reason is that the height spurt precedes increases in bone mass, making young adolescents particularly vulnerable to fractures (Mathison & Agrawal, 2011).

One organ system, the lymphoid system (which includes the tonsils and adenoids), decreases in size, so teenagers are less susceptible to respiratory ailments. Mild asthma, for example, often switches off at puberty—

Another organ system, the skin, becomes oilier, sweatier, and more prone to acne. Hair also changes, becoming coarser and darker. New hair grows under arms, on faces, and over sex organs (pubic hair, from the same Latin root as puberty). Visible facial and chest hair is sometimes considered a sign of manliness, although hairiness in either sex depends on genes as well as on hormones. Girls pluck or dye any facial hair they see and shave their legs, while boys proudly grow sideburns, soul patches, chinstraps, moustaches, and so on—

Often teenagers cut, style, or grow their hair in ways their parents do not like, as a sign of independence. To become more attractive, many adolescents spend considerable time, money, and thought on their visible hair—

Diet Deficiencies

All the changes of puberty depend on adequate nourishment, yet many adolescents do not eat well. Teenagers often skip breakfast, binge at midnight, guzzle down soda, and munch on salty, processed snacks. One reason for their eating patterns is that their hormones affect their diurnal rhythms, including their appetites; another reason is that their drive for independence makes them avoid family dinners and refuse to eat what their mother says they should.

Cohort and age are crucial. In the United States, each new generation eats less well than the previous one, and each 18-

Deficiencies of iron, calcium, zinc, and other minerals are especially common during adolescence. Because menstruation depletes iron, anemia is more likely among adolescent girls than among any other age group. This is true everywhere, especially in South Asia and sub-

Reliable laboratory analysis of blood iron on a large sample of young girls in developing nations is not available, but a study of 18-

Boys everywhere may also be iron-

Similarly, although the daily recommended intake of calcium for teenagers is 1,300 milligrams, the average U.S. teen consumes less than 500 milligrams a day. About half of adult bone mass is acquired from ages 10 to 20, which means many contemporary teenagers will develop osteoporosis (fragile bones), a major cause of disability, injury, and death in late adulthood. [Lifespan Link: Osteoporosis is discussed in Chapter 23.]

One reason for calcium deficiency is that milk drinking has declined. In 1961, most North American children drank at least 24 ounces (about ¾ liter) of milk each day, providing almost all (about 900 milligrams) of their daily calcium requirement. Fifty years later, only 15 percent of high school students drank that much milk (MMWR, June 8, 2012). In the twenty-

Choices Made

Many economists advocate a “nudge” to encourage people to make better choices, not only in nutrition but also in all other aspects of their lives (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). Teenagers are often nudged in the wrong direction. Nutritional deficiencies result from the food choices that young adolescents are enticed to make.

Fast-

Furthermore, nutritional deficiencies increase when schools have vending machines that offer soda and snacks, especially for middle school students (Rovner et al., 2011). A constructive nudge of higher prices for, and less attractive placement of, junk foods as well as healthier selections for in-

A more drastic strategy would be to ban the purchase of unhealthy foods in schools altogether—

Not surprisingly, rates of obesity are falling in childhood but not in adolescence. Only three U.S. states (Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee) had high school obesity rates at 15 percent or more in 2003; 12 states were that high in 2011.

Body Image

body image A person’s idea of how his or her body looks.

One reason for poor nutrition among teenagers is anxiety about body image—

Few adolescents are happy with their bodies, partly because almost none look like the bodies portrayed in magazines, videos, and so on marketed to teenagers (Bell & Dittmar, 2010). Unhappiness with appearance is worldwide. A longitudinal study in Korea found that body image dissatisfaction began at about age 10 and increased until age 15 or so, increasing depression and thoughts of suicide (Kim & Kim, 2009). Adolescents in China have anxieties about weight gain similar to those of U.S. teenagers (Chen & Jackson, 2009).

Eating Disorders

Dissatisfaction with body image can be dangerous, even deadly. Many teenagers, mostly girls, eat erratically or ingest drugs (especially diet pills) to lose weight; others, mostly boys, take steroids to increase muscle mass. Eating disorders are rare in childhood but increase dramatically at puberty, accompanied by distorted body image, food obsession, and depression (Bulik et al., 2008; Hrabosky & Thomas, 2008). Such disorders are often unrecognized and untreated until they get worse in adulthood.

Adolescents sometimes switch from obsessive dieting to overeating to overexer-

Anorexia Nervosa

anorexia nervosa An eating disorder characterized by self-

A body mass index (BMI) of 18 or lower, or loss of more than 10 percent of body weight within a month or two, indicates anorexia nervosa, a disorder characterized by voluntary starvation. The person becomes very thin, risking death by organ failure. Staying too thin becomes an obsession. People suffering from anorexia refuse to eat normally because their body image is severely distorted; they may believe they are too fat when actually they are dangerously underweight.

Although anorexia existed earlier, it was not identified until about 1950, when some high-

Binge Eating

bulimia nervosa An eating disorder characterized by binge eating and subsequent purging, usually by induced vomiting and/or use of laxatives.

About three times as common as anorexia is bulimia nervosa (also called the binge–

Binging and purging are common among adolescents. For instance, a survey found that in the last 30 days of 2012, 6 percent of U.S. high school girls and 3 percent of the boys vomited or took laxatives to lose weight, with marked variation by state, from 4 percent in Oklahoma to 10 percent in Louisiana (MMWR, June 8, 2012).

Some adolescents periodically and compulsively overeat, quickly consuming large amounts of ice cream, cake, or any snack food until their stomachs hurt. Such binging is typically done in private, at least weekly for several months. The sufferer does not purge (hence this is not bulimia) but feels out of control, distressed, and depressed. This is a new disorder recognized in DSM 5 as binge eating disorder.

All adolescents are vulnerable to eating disorders of many kinds. They try new diets, go without food for 24 hours (as did 13 percent of U.S. high school girls in the last month in 2011), or take diet drugs (6 percent) (MMWR, June 8, 2012). Many eat oddly (e.g., only rice or only carrots) or begin unusual diets.

Each episode of bingeing, purging, or fasting makes the next one easier. A combination of causes leads to obesity, anorexia, bulimia, or bingeing, with at least five general elements—

As might be expected from a developmental perspective, healthy eating begins with childhood habits and family routines. Most overweight or underweight infants never develop nutritional problems, but children who are overweight or underweight are at greater risk. Particularly in adolescence, family-

SUMMING UP

The transformations of puberty are dramatic. Boys and girls become men or women, both physically and neurologically. Growth proceeds from the extremities to the center, so the limbs grow before the internal organs do. Increase in weight precedes that in height, which precedes growth of the muscles and of the internal organs.

All adolescents are vulnerable to poor nutrition; few are well nourished. Insufficient consumption of iron and calcium is particularly common as fast food and nutrient-